Jacob Boehme Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob Onyumbe Dissertation

Piles of Slain, Heaps of Corpses: Lament, Lyric, and Trauma in the Book of Nahum by Jacob Onyumbe Wenyi The Divinity School Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Ellen F. Davis, Supervisor ___________________________ Stephen B. Chapman ___________________________ Anathea Portier-Young ___________________________ Gerald O. West Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Theology in the Divinity School of Duke University 2017 i v ABSTRACT Piles of Slain, Heaps of Corpses: Lament, Lyric, and Trauma in the Book of Nahum by Jacob Onyumbe Wenyi The Divinity School Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Ellen F. Davis, Supervisor ___________________________ Stephen B. Chapman ___________________________ Anathea Portier-Young ___________________________ Gerald O. West Abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Theology in the Divinity School of Duke University 2017 i v Copyright by Jacob Onyumbe Wenyi 2017 i v Abstract With its description of God as wrathful and vengeful and its graphic depiction of war and violence, Nahum has often been treated as a dangerous book, both in church settings and in academic circles. This dissertation is an effort to confront violence, both in my community and in the book of Nahum. It is a contextual reading of Nahum against the background of the wars that have plagued my country, the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the early 1990s. It argues that Nahum’s description of God and its depiction of war scenes were meant to evoke in seventh-century BCE Judahite audiences the memory of war and destruction at the hands of the Assyrians. -

Jacob Bergsbaken Humanitarian Scholarship

Jacob Bergsbaken Humanitarian Scholarship This scholarship fund was established in loving memory of Jacob Bergsbaken by his parents Randy and Beth Bergsbaken. Jacob attended Bonduel High school where he was an honor student. He was also an avid wrestling fan and loved watching it on TV. At age 16, Jacob lost his long and courageous battle with Muscular Dystrophy. Eligibility: Graduates from Bonduel High School who plan to attend a college, university or technical college. Classroom teachers will submit nominations for students that posses the following characteristics: Excellence in humanitarian efforts towards others involving: o Kindness o Caring o Compassion o Dignity o Respect Award Amount: One non-renewable $500 scholarship award for tuition expenses. Selection: Students will be nominated by classroom teachers. All nominations will then be reviewed by the Bonduel High School Scholarship Selection Committee, who will determine the recipient. Payment Procedure: Scholarship payments will be released after submission of the following to the Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region: completed scholarship verification form (located at www.cffoxvalley.org/scholarships), verification of full time student status (class schedule with credits listed). After approval of submitted documentation, the scholarship check will be paid directly to the school the recipient will be attending during the first semester of the freshman year of college. This scholarship cannot be deferred. Most communications between the Community Foundation and the student will be via email. Please keep us advised of your current email address. Loss of Eligibility: Failure to register as a full time student for the first semester of freshman year of college. -

The Corona Show James Corbett's Wake-Up Call COVID-19 and The

Volume 5/No. 9/10 May/June 2020 THE PRESENT AGE A monthly international magazine for the advancement of Spiritual Science The Corona Show James Corbett’s Wake-up Call COVID-19 and the Cosmos Thinking: Its Freedom or Prohibition? The Incarnation of Ahriman (part two) Corona: Connecting the Dots Vaccines: C.A.Fitts and J.Rappoport CHF 22 / £ 15 / $ 22 / € 20 Symptomatic Essentials in politics, culture and economy Essentials in politics, culture / $ 22 € 20 Symptomatic CHF 22 / £ 15 World Dictatorship, Prophecies and the Jolt Contents towards the Spirit Beyond Surprise 3 No world dictator would have been able to achieve in a few weeks what the “virus”, Some Reflections on the Corona Crisis against which no remedy has allegedly yet been found, has been able to achieve T.H. Meyer in such a short time: school closures, the banning of public gatherings, theatre, concert and cinema performances, and visits to restaurants. Closed frontiers, closed A Letter to the Future 5 bars, and at the few open shops and pharmacies the notice that payment will only James Corbett be accepted with contactless cards. Economies shut down. No international de- Anti-Corona 2020 6 cision could have had so much psychological propaganda for the long-planned Martin Meyer Editorial global abolition of cash. This is a corona dictatorship still just short of forced vacci- - nation. Overnight everything else, such as climate change and 5G, has become an “…the diseases we suffer work unimportant secondary question. But there are also good things to report: NATO’s on earth are visitations from heaven” 8 gigantic NATO “Defender 2020” manoeuvres have been cancelled! COVID-19 and the Cosmos And sober explanations of the medical exaggerations have been provided by Terry Boardman Profs. -

The Etiology of Character Realization, Within Rhetorical Analysis of the Series

i Found: The Etiology of Character Realization, within Rhetorical Analysis of the Series LOST, through the Application of Underhill’s and Turner’s Classic Concepts of the Mystic Journey ____________________________________________ Presented to the Faculty Liberty University School of Communication Studies ______________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication By Lacey L. Mitchell 2 December 2010 ii Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in Communication Studies Michael P. Graves Ph.D., Chair Carey Martin Ph.D., Reader Todd Smith M.F.A, Reader iii Dedication For James and Mildred Renfroe, and Donald, Kim and Chase Mitchell, without whom this work would have been remiss. I am forever grateful for your constant, unwavering support, exemplary resolve, and undiscouraged love. iv Acknowledgements This work represents the culmination of a remarkable journey in my life. Therefore, it is paramount that I recognize several individuals I found to be indispensible. First, I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Michael Graves, for taking this process and allowing it to be a learning and growing experience in my own journey, providing me with unconventional insight, and patiently answering my never ending list of inquiries. His support through this process pushed me towards a completed work – Thank you. I also owe a great debt to the readers on my committee, Dr. Cary Martin and Todd Smith, who took time to ensure the completion of the final product. I will always have immense gratitude for my family. Each of them has an incredible work ethic and drive for life that constantly pushes me one step further. -

The Vilcek Foundation Celebrates a Showcase Of

THE VILCEK FOUNDATION CELEBRATES A SHOWCASE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS AND FILMMAKERS OF ABC’S HIT SHOW EXHIBITION CATALOGUE BY EDITH JOHNSON Exhibition Catalogue is available for reference inside the gallery only. A PDF version is available by email upon request. Props are listed in the Exhibition Catalogue in the order of their appearance on the television series. CONTENTS 1 Sun’s Twinset 2 34 Two of Sun’s “Paik Industries” Business Cards 22 2 Charlie’s “DS” Drive Shaft Ring 2 35 Juliet’s DHARMA Rum Bottle 23 3 Walt’s Spanish-Version Flash Comic Book 3 36 Frozen Half Wheel 23 4 Sawyer’s Letter 4 37 Dr. Marvin Candle’s Hard Hat 24 5 Hurley’s Portable CD/MP3 Player 4 38 “Jughead” Bomb (Dismantled) 24 6 Boarding Passes for Oceanic Airlines Flight 815 5 39 Two Hieroglyphic Wall Panels from the Temple 25 7 Sayid’s Photo of Nadia 5 40 Locke’s Suicide Note 25 8 Sawyer’s Copy of Watership Down 6 41 Boarding Passes for Ajira Airways Flight 316 26 9 Rousseau’s Music Box 6 42 DHARMA Security Shirt 26 10 Hatch Door 7 43 DHARMA Initiative 1977 New Recruits Photograph 27 11 Kate’s Prized Toy Airplane 7 44 DHARMA Sub Ops Jumpsuit 28 12 Hurley’s Winning Lottery Ticket 8 45 Plutonium Core of “Jughead” (and sling) 28 13 Hurley’s Game of “Connect Four” 9 46 Dogen’s Costume 29 14 Sawyer’s Reading Glasses 10 47 John Bartley, Cinematographer 30 15 Four Virgin Mary Statuettes Containing Heroin 48 Roland Sanchez, Costume Designer 30 (Three intact, one broken) 10 49 Ken Leung, “Miles Straume” 30 16 Ship Mast of the Black Rock 11 50 Torry Tukuafu, Steady Cam Operator 30 17 Wine Bottle with Messages from the Survivor 12 51 Jack Bender, Director 31 18 Locke’s Hunting Knife and Sheath 12 52 Claudia Cox, Stand-In, “Kate 31 19 Hatch Painting 13 53 Jorge Garcia, “Hugo ‘Hurley’ Reyes” 31 20 DHARMA Initiative Food & Beverages 13 54 Nestor Carbonell, “Richard Alpert” 31 21 Apollo Candy Bars 14 55 Miki Yasufuku, Key Assistant Locations Manager 32 22 Dr. -

Good Morning Ladies and Gentlemen. My Name Is Jacob Gregg

Good morning Ladies and Gentlemen. My name is Jacob Gregg. Before I get started, I’d like to take a moment to thank Senator Brenner who invited me here to speak. He has been kind enough to take the time to listen, educate, and encourage me and I truly appreciate that. I’m here this morning to appeal to you to give back something that was taken from me: my senior year. I, along with 108,000 other Ohio High School seniors, were 2020 Juniors when COVID caused the nationwide quarantine. We lost spring sports, prom, academic competitions, volunteer opportunities such as Special Olympics, Our Night to Shine prom, Repair Affair, and of course in-person learning. Over the summer, things only continued to worsen. Student athletes like myself were prevented from visiting college campuses, attending camps, showcases and combines in hopes of getting the attention of a college scout. We couldn’t even get together to train with friends. Gyms were closed. Heck, I couldn’t even get a haircut! Church camps were cancelled, apprenticeship programs were discontinued. AP classes, taking the ACT, … the list goes on and on. When school began in the fall, there was some hope that things might return to normal, but we were not so lucky. I am not too proud to admit that I am dangerously close to failing my senior year of high school. At the onset of COVID, my GPA was a respectable 3.8. Now? I’m barely hanging in there with a 2.1. Have you ever tried to teach yourself Calculus? How about Anatomy? Government? What about a foreign language? I don’t recommend it. -

Bachelorarbeit

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Sebastian Dorn Konfliktgestaltung – Ursachen, Arten, Bewältigung Eine Darstellung am Beispiel der US-Erfolgsserie „LOST“ 2013 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Konfliktgestaltung – Ursachen, Arten, Bewältigung Eine Darstellung am Beispiel der US-Erfolgsserie „LOST“ Autor: Sebastian Dorn Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF10w1 Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. Detlef Gwosc Zweitprüfer: Dipl. Foto-Ingenieur Achim Dunker Einreichung: Darmstadt, 05.08.2013 Faculty Of Media BACHELOR THESIS Forming conflict – sources, types, handling A presentation at the US-series “LOST” author: Sebastian Dorn course of studies: film and television seminar group: FF10w1 first examiner: Prof. Dr. Detlef Gwosc second examiner: Dipl. Foto-Ingenieur Achim Dunker submission: Darmstadt, August, 05th, 2013 __________________________________________________________________________ Bibliografische Angaben Nachname, Vorname: Dorn, Sebastian Thema der Bachelorarbeit: Konfliktgestaltung – Ursachen, Arten, Bewältigung Eine Darstellung am Beispiel der US-Erfolgsserie „LOST“ Topic of thesis: Forming conflict – sources, types, handling A presentation at the US-series “LOST” 72 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2013 Abstract In dieser Bachelorarbeit geht es um die Untersuchung der dargestellten Konflikte in der US-Serie LOST. Die amerikanische Erfolgsserie ist mit sämtlichen Konfliktsituationen bestückt, die in dieser Arbeit in Bezug auf Ursachen, Arten und Umgang genauer überprüft werden. Dabei -

350Th Anniversary of Jews in America

HERITAGE Newsletter of the American Jewish Historical Society VOL.2 NO.1 SPRING 2004 350th Anniversary of Jews in America Jewish Rights in 1654 First Jewish Feminist Vindication of a Patriot Baseball Stories Justice Cardozo Nice Jewish Boy from Krypton American Jewish Historical Society 2003-2004 Gift Roster Over $250,000 Mayor Michael Bloomberg Isaac and Ivette Davah Helen Portnoy Richard A. Eisner Ruth and Sidney Lapidus Roger Blumencranz Betty and Robert David Irving W. Rabb Benjamin Feldman Genevieve and Justin L. Wyner Mr. and Mrs. Maxwell Burstein Richard and Rosalee Davison Dina Recanati Kenneth First Marshall Dana Dommert Phillips, LP Richard Reiss Joan and Aaron Fischer $100,000 + Douglas Durst Dr. and Mrs. Ronald I. Dozoretz Robert S. Rifkind Hilda Fischman Barbara and Ira Lipman Dinah A. and Uri Evan Jack A. Durra Rizzoli Intnl. Publications Inc. Richard Foreman Marion and George Blumenthal Andrew Farkas Sharon Ann Dror David Rockefeller Alan J. & Susan A. Fuirst Anne E. and Kenneth J. Bialkin Richard Fuld Sybil and Alan M. Edelstein Mrs. Frederick Rose Philanthropic Fund The Gottesman Fund Victor Elmaleh Frances and Harold S. Rosenbluth Rita and Henry Kaplan $25,000 + Don Garber Mr. and Mrs. Richard England Mr. and Mrs. Abraham Rosenthal Bernard Friedman National Foundation for Jewish Rob Glazer Charles Evans Doris Rosenthal Ellen Friedman Culture Shep Goldfein Eli N. Evans Chaye H. and Walter Roth Mr. and Mrs. Howard L. Ganek Len Blavatnik Dr. Jerome D. Goldfisher Dinah A. Evan Joan and Alan P. Safir Philip Garoon and Family Citigroup Foundation Richard N. Goldman Geraldine Fabrikant Arnold Saltzman Rabbi David Gelfand Ted Cutler Milton M. -

Jacob Davis: His Life and Contributions

JACOB DAVIS: HIS LIFE AND CONTRIBUTIONS * Born Jacob Youphes in Riga, Latvia, 1831. * Came to America and in 1854, changed his name to Jacob Davis. Operated a tailor shop in New York City and Augusta, Maine. * Moved to San Francisco in 1856, then moved to the gold country town of Weaverville, working as a tailor. In 1858 he left California for western Canada (likely Cariboo and Victoria, British Columbia), where he lived for nine years. * He married Annie (Parksher/Packscher) from Germany, in 1865. They had six children. * Davis returned to San Francisco from Victoria, B.C. in January of 1867. Then he moved to Virginia City, Nevada where he opened a cigar store. Three months later, however, he was working again as a tailor. * In June of 1868 he settled in the little railroad town of Reno, Nevada. He invested his money in a brewery but lost it all. By 1869 he had opened a tailoring shop on Virginia Street. He began making wagon covers and tents from an off-white cotton duck cloth which he purchased from the wholesale house of Levi Strauss & Co. beginning in 1870. * In late 1870 a woman customer came to him for a pair of “cheap” pants for her “large” husband who had a habit of going through pants rather quickly. She paid him $3.00 in advance for the white duck pants, and told Davis she wanted them made as strong as possible. * Davis had some copper rivets in his shop, which he used to attach straps to the horse blankets he made for local teamsters. -

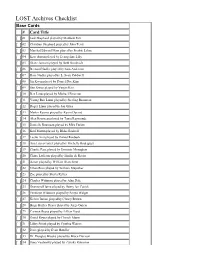

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika -

TV/Series, Hors Séries 1 | 2016 Lost, Or a Guide for the Lovesick 2

TV/Series Hors séries 1 | 2016 Lost: (re)garder l'île Lost, or a Guide for the Lovesick Pacôme Thiellement Translator: Brian Stacy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/4978 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.4978 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Pacôme Thiellement, « Lost, or a Guide for the Lovesick », TV/Series [Online], Hors séries 1 | 2016, Online since 01 December 2020, connection on 05 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/tvseries/4978 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/tvseries.4978 This text was automatically generated on 5 December 2020. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Lost, or a Guide for the Lovesick 1 Lost, or a Guide for the Lovesick Pacôme Thiellement Translation : Brian Stacy 1 In a work on Bouvard and Pécuchet, Raymond Queneau singled out two defining lines in the History of the novel: that of the Iliad, and that of the Odyssey. Every great work is either an Iliad or an Odyssey, the odysseys being far superior in number than the iliads: the Satiricon, The Divine Comedy, Pantagruel, Don Quixote and of course Ulysses are odysseys, that is to say, des récits de temps pleins. The iliades are, on the contrary, searches for lost time: facing Troy, on a deserted island or at the Guermantes'1. 2 Lost falls along both, but more importantly, it splits its narrative content into two levels: a contemplative level, that of the Brahmins, of the priests, the story of the election to become protector of the island, which is also a story of discipleship and obedience; and another level, active but true to sacred principles, that of the ksatriyas or knights, the story of "adventures" seeking the return of a loved one, Desmond's storyline. -

A Biographical Study of Jacob

Scholars Crossing Old Testament Biographies A Biographical Study of Individuals of the Bible 10-2018 A Biographical Study of Jacob Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ot_biographies Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "A Biographical Study of Jacob" (2018). Old Testament Biographies. 49. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ot_biographies/49 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the A Biographical Study of Individuals of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Old Testament Biographies by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jacob CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY I. Jacob, the younger twin A. His birth was God’s answer to Isaac’s and Rebekah’s prayer concerning children (Gen. 25:21-23). 1. God told them two nations were in Rebekah’s womb. 2. One nation would be stronger than the other. 3. The older twin would serve the younger twin. B. Jacob was thus the second born of twins (Gen. 25:24-26). C. He was born with his hand grasping Esau’s heel (Gen. 25:26). II. Jacob, the devising brother A. In contrast to Esau, who was an outdoorsman and a hunter, Jacob grew up a quiet man, staying among the tents (Gen. 25:27). B. Jacob persuaded his famished brother Esau, who was returning from a hunting trip, to sell him the firstborn birthright for some bread and lentil stew (Gen.