The Prairie Connect Spring 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers

Publish Authors Emily Harstone Authors Publish The 2021 Guide to Manuscript Publishers 230 Traditional Publishers No Agent Required Emily Harstone This book is copyright 2021 Authors Publish Magazine. Do not distribute. Corrections, complaints, compliments, criticisms? Contact [email protected] More Books from Emily Harstone The Authors Publish Guide to Manuscript Submission Submit, Publish, Repeat: How to Publish Your Creative Writing in Literary Journals The Authors Publish Guide to Memoir Writing and Publishing The Authors Publish Guide to Children’s and Young Adult Publishing Courses & Workshops from Authors Publish Workshop: Manuscript Publishing for Novelists Workshop: Submit, Publish, Repeat The Novel Writing Workshop With Emily Harstone The Flash Fiction Workshop With Ella Peary Free Lectures from The Writers Workshop at Authors Publish The First Twenty Pages: How to Win Over Agents, Editors, and Readers in 20 Pages Taming the Wild Beast: Making Inspiration Work For You Writing from Dreams: Finding the Flashpoint for Compelling Poems and Stories Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 13 Nonfiction Publishers.................................................................................................. 19 Arcade Publishing .................................................................................................. -

Literary Agent Michael Larsen

10 Commandments That Guarantee Your Success Handouts for a Keynote/Seminar Michael Larsen Michael Larsen-Elizabeth Pomada Literary Agents Co-director, San Francisco Writers Conference San Francisco Writing for Change Conference Author of How to Write a Book Proposal and How to Get a Literary Agent From which many of the handouts were adapted Coauthor of Guerrilla Marketing for Writers: 100 Weapons for Selling Your Work With Jay Conrad Levinson, Rick Frishman, and David Hancock Michael Larsen Michael Larsen. The commandments are the outline of a keynote and seminar. Michael Larsen-Elizabeth Pomada Literary Agents/ AAR / Helping Writers Launch Careers Since 1972 [email protected] / www.larsenpomada.com / 415-673-0939 /1029 Jones Street / San Francisco, 94109 The 12th San Francisco Writers Conference / A Celebration of Craft, Commerce & Community February 12-16, 2015 / www.sfwriters.org / [email protected] / Mike’s blog: http://sfwriters.info/blog Keynotes: Judith Curr, Yiyun Li @SFWC / www.facebook.com/SanFranciscoWritersConference The 7th San Francisco Writing for Change Conference / Changing the World One Book at a Time September, 12th, 2015 / www.sfwritingforchange.org / [email protected] Mike’s blog: http://sfwriters.info/blog / @SFWC / www.facebook.com/SanFranciscoWritersConference 0 A Golden Age for Writers: 10 Truths You Need to Know About Writing and Publishing To be a successful, you need a positive but realistic perspective about writing and publishing. These ten observations form the basis for “10 Commandments that, with Luck, Guarantee Your Success as a Writer.” 1. Because the Web empowers you to reach readers, control and profit more from your work, collaborate on monetizing and publicizing your work, and change the world faster and more easily than ever, now is the best time ever to be a writer. -

The NWU Literary Agent Agreement” 6/19/08 10:57 PM

Loading “The NWU Literary Agent Agreement” 6/19/08 10:57 PM The NWU Literary Agent Agreement (Confidential: For NWU members only) Understanding the Author-Agent Relationship A Guide to the NWU Preferred Literary Agent Agreement Introduction This guide is an educational tool for authors who are considering entering into a relationship with a literary agent, or who need help in understanding an existing author- agent agreement. It should be read in conjunction with the National Writers Union Preferred Literary Agent Agreement and used to evaluate or improve any agent agreement you may be asked to sign. Both documents are available to National Writers Union (NWU) members. Deciding to retain an agent is a major decision in any author\'s career. An agent will agree to represent your work because she believes she can sell it to a publisher or publishers. The agent is your representative, whom you hire to market your work, to negotiate your publishing contracts, and to oversee your royalty accounts. In exchange for an agent\'s representation, an author agrees to pay the agent a commission; a commission is a percentage of all income earned from those rights that the agent is able to license. Every author\'s work includes a bundle of individual rights that may be exploited: e.g., hardcover print rights; paperback print rights; electronic database rights; interactive software rights; foreign translation rights; television adaptation rights; audio cassette rights, and so forth. In addition, as new forms of media are created, new rights (e.g., CD-ROM rights) emerge and become valuable. Collectively, these individual rights form the copyright to one\'s work. -

PW Show Daily the World Within Reach

PW Show Daily The World Within Reach The consummate guide to all leading international trade shows, Show Dailies are unique opportunities to optimize your investment and stand out in a crowded marketplace. Distributed on-site throughout each venue, Show Dailies are the most potent tool for increasing visibility, driving traffic and boosting sales on the spot. And awareness extends far beyond a single event with supplements circulated to PW’s loyal print and digital readership of 68K, ensuring you never get lost in the crowd. Bologna MARCH 26, 2018 VISIT PW AT HALL 26 B38 Big, Bold Moves London Book Fair The Bologna Children’s Book Fair is updating its facilities and reaching out to new audiences, including, for the March 12–14 first time, booksellers BY ED NAWOTKA This year’s Bologna Children’s Book Fair has a different look for the 1,300 exhibitors and other industry members expected for the 2018 event. The biggest change is the new construction to the fairgrounds. As part of the process halls 29 and 30 have been dismantled, and the exhibitors who usually exhibit there have been moved to halls 21, 22, and 32. “It was a challenge to move everyone, largely because the shape of the halls is different,” says Elena Pasoli, group product manager of the fair. “But it is only for one year.” She notes that halls 29 and 30 will reopen next year, which Silvana Sola, curator of the Children’s Books on Art project will again require another move. “It is a challenge for some and professor of history of illustration at Istituto Superiore publishers, but we really think they are going to love the per le Industrie Artistiche in Urbino, Italy; and others. -

The Swetky Agency

THE SWETKY AGENCY LITERARY AGENCY AGREEMENT http://amsaw.org/index-agency.html Faye M. Swetky, Representative/Owner : [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________ AGREEMENT (hereinafter, "Agreement"), dated ________, sets forth the relationship between the literary agent, The Swetky Agency, 2150 Balboa Way No. 29, St. George, UT 84770 (hereinafter, "Literary Agent"), and the author, _____________, of ____________________________________________ (hereinafter, "Author"). 1. LITERARY AGENT REPRESENTS AUTHOR For the term of this agreement, Author hereby retains Literary Agent: (a) To represent Author for the sale of all of the following works (hereinafter, "Represented Works"), written or to be written by Author and not covered by a prior un-agented sale or prior agency agreement: (1) all book-length fiction and/or non-fiction; (2) all full-length feature screenplays and/or full-length or series-length television scripts, and (3) any other writings that Author and Literary Agent may agree upon and specifically stipulate in writing, unless the agency deems the property to be unmarketable in its presented form. Author hereby agrees to make available to Literary Agent all above mentioned works for consideration for representation. (b) To negotiate sales (hereinafter, "Represented Sales") of (1) Represented Works in the U.S., its territories, and Canada (hereinafter, "Domestic Sales"), (2) Represented Works in non-domestic markets (hereinafter, "Foreign Sales"), and (3) derivative or secondary rights in the Represented Works (such as film, TV, recording, or other dramatic media) anywhere in the world (hereinafter, "Subsidiary Sales"). (c) To receive payments and royalties from all Represented Sales so long as the contracts for such sales remain in force. -

Electrifying Emotion

MY ROAD TO TRADITIONAL PUBLICATION David R Slayton - Author WHO AM I? Or better yet, why am I the one teaching this? I’m David R. Slayton. I live in Denver, Colorado. I’ve been writing fantasy, epic, urban, and YA for about a decade now. This year I published my debut novel, White Trash Warlock, with Blackstone Publishing. It’s been a long journey with several books, two agents, and a lot of rejection. I want to share some of what I learned about the process with you and hope that it helps. ABOUT ADVICE As you write and attend workshops, etc. you’re going to get a lot of advice. And you’re going to hear that there’s only one way to do it. This is very wrong. Take all advice, including mine, with skepticism. Keep what helps you. Discard what doesn’t. There is rarely a single solution to publishing or a path forward for your writing. Whatever advice you receive, please don’t let anyone take your writing from you. WHY TRADITIONAL PUBLISHING? First, I want to emphasize that there is nothing wrong with or inherently better or worse about indie versus traditional publishing. There are pros and cons to each. It’s about picking the right path for your work. I chose traditional publishing for specific reasons: I wanted the wider distribution possibilities. I wanted a partner in marketing, promotion, etc. I wanted editors who would make my books stronger. I didn’t want to have to produce my own audiobook. I wanted to be able to submit for a wider array of awards, etc. -

Faqs from ASPIRING AUTHORS

FAQS FROM ASPIRING AUTHORS What does ‘no unsolicited submissions’ actually mean? A publisher who doesn’t accept unsolicited material only reads manuscripts sent via a literary agent or scout. Chicken House doesn’t accept unsolicited manuscripts or synopses, nor can we enter into correspondence regarding new authors’ work. Although this can be frustrating for authors, the reality is that it simply isn’t possible for a publisher to sift through the vast number of unsolicited submissions received. However, we do run the Times/Chicken House Children’s Fiction Competition in partnership with the Times newspaper. The winner will go on to have their manuscript published by Chicken House. We guarantee that, provided it meets all entry requirements, your manuscript will be read. I’m new to publishing but I want to send my work out. Who can I send it to? We advise all new children’s authors to consult the latest version of The Children’s Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, which contains comprehensive listings of credible literary agents and publishers, plus details of the kinds of stories they are looking for. It will also tell you which agents/publishers are currently accepting unsolicited manuscripts. If I find a publisher/literary agent that accepts unsolicited manuscripts, how can I make my work stand out before I send it off? Ensure that your work is in tip-top condition – edit your book to the best of your ability, proofread it and ensure it’s immaculately presented. Learn how to write a pithy, engaging synopsis and a brief, polite and noteworthy covering letter. -

Literary Agents Who Represent Christian Authors.Pages

Updated:! 7/15/14 !1 FOREWORD! Thanks for downloading this resource guide. I don’t know of anything else like it available anywhere. Let me tell you how it came about.! Several years ago, when I was the Chairman and CEO of Thomas Nelson Publishers, I was routinely asked by authors for agent recommendations. Like nearly all publishers today, we didn’t accept unsolicited proposals or manuscripts. They had to be referred by a literary agent. ! That put me in a quandary. As the largest Christian publisher in the world, we did business with all the agents. I didn’t want to recommend my personal favorites and risk alienating the others. Instead, I wanted to refer aspiring authors to an official list of recognized agents. From there, they could make their own connections.! Only one problem: I couldn’t find such a list anywhere. As a result, I decided to create one.! Using my blog, I put out a call for interested agents to submit their contact information to me. In order to ensure that I only included legitimate, experienced agents, I required each one to provide a list of at least three clients for whom they had secured traditional publishing contracts.! I published that first list in 2007. I have updated it every year since then. The resource you are reading now contains every agent active in the Christian book publishing market today. (The only exception are two or three agents who are currently not accepting new clients.) My goal is to save you the enormous effort it would take to create this list on your own.! Now, before you start emailing or contacting the agents on this list, let me provide a few suggestions:! Updated:! 7/15/14 !2 1. -

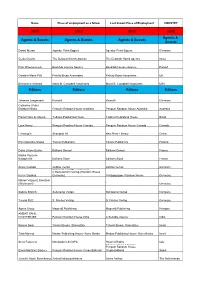

2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents

Name Place of employment as a fellow Last known Place of Employment COUNTRY 2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Scouts Daniel Mursa Agentur Petra Eggers Agentur Petra Eggers Germany Geula Geurts The Deborah Harris Agency The Deborah Harris Agency Israel Piotr Wawrzenczyk Book/lab Literary Agency Book/lab Literary Agency Poland Caroline Mann Plitt Felicity Bryan Associates Felicity Bryan Associates UK Beniamino Ambrosi Maria B. Campbell Associates Maria B. Campbell Associates USA Editors Editors Editors Editors Johanna Langmaack Rowohlt Rowohlt Germany Catherine (Cate) Elizabeth Blake Penguin Random House Australia Penguin Random House Australia Australia Flavio Rosa de Moura Todavia Publishing House Todavia Publishing House Brazil Lynn Henry Penguin Random House Canada Penguin Random House Canada Canada Li Kangqin Shanghai 99 New River Literary China Päivi Koivisto-Alanko Tammi Publishers Tammi Publishers Finland Dana Liliane Burlac Éditions Denoël Éditions Denoël France Maÿlis Vauterin- Bacqueville Editions Stock Editions Stock France Anvar Cukoski Aufbau Verlag Aufbau Verlag Germany Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and C.Bertelsmann Verlag (Random House Karen Guddas Germany) Verlagsgruppe Random House Germany Marion Vazquez Boerzsei (Wichmann) ` ` Germany Sabine Erbrich Suhrkamp Verlag Suhrkamp Verlag Germany Teresa Pütz S. Fischer Verlag S. Fischer Verlag Germany Ágnes Orzóy Magvető Publishing Magvető Publishing Hungary AMBAR SAHIL CHATTERJEE Penguin Random House India A Suitable Agency India Ronnie -

What Editors Do , ,

What Editors Do , , Edited by The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London ............ Th e Th ree Phases of Editing / 1 . : 1 by Peter Ginna / 17 2 : Twelve Rules for Trade Editors by Jonathan Karp / 30 3 : Th e How and Why of Academic Publishing by Gregory M. Britton / 40 4 : Acquiring College Textbooks by Peter Coveney / 49 . : 5 by Nancy S. Miller / 59 6 : Th e Author– Editor Relationship by Betsy Lerner / 69 7 : What I Learned about Editing When I Became a Literary Agent by Susan Rabiner / 77 8 - , Developmental Editing by Scott Norton / 85 9 : On Line Editing by George Witte / 96 10 , , : What Copyeditors Do by Carol Fisher Saller / 106 . : 11 : Th e Editor as Manager by Michael Pietsch / 119 12 : Th e Editor as Evangelist by Calvert D. Morgan Jr. / 131 13 - : Independent Publishing and Community by Jeff Shotts / 141 . : 14 : Editing Literary Fiction by Erika Goldman / 151 15 , , : Editing Genre Fiction by Diana Gill / 159 16 : On Editing General Nonfi ction by Matt Weiland / 169 17 : Editing Books for Children by Nancy Siscoe / 177 18 : Editing Biography, Autobiography, and Memoir by Wendy Wolf / 187 19 : Editing Works of Scholarship by Susan Ferber / 197 20 : Reference Editing and Publishing by Anne Savarese / 205 21 : Creating Illustrated Books by Deb Aaronson / 213 . : 22 : Why Publishing Needs Diversity by Chris Jackson / 223 23 : On Being an Editorial Assistant by Katie Henderson Adams / 231 24 : Making a Career as a Freelance Editor by Katharine O’Moore- Klopf / 238 25 - - by Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry / 248 26 : Th e Editor’s Role in a Changing Publishing Industry by Jane Friedman / 256 . -

Are Literary Agents (Really) Fiduciaries?

Pittsburgh University School of Law Scholarship@PITT LAW Articles Faculty Publications Summer 2019 Are Literary Agents (Really) Fiduciaries? Jacqueline Lipton University of Pittsburgh School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Consumer Protection Law Commons, Contracts Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Legal Profession Commons, Music Business Commons, Other Music Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Jacqueline Lipton, Are Literary Agents (Really) Fiduciaries?, 86 Tennessee Law Review 825 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles/180 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship@PITT LAW. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@PITT LAW. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ARE LITERARY AGENTS (REALLY) FIDUCIARIES? JACQUELINE D. LIPTON INTRODUCTION ............................................. 826 I. AGENCY LAW, FIDUCIARY PRINCIPLES, AND LITERARY AGENTS ............................................ 828 II. LITERARY AGENTS' OBLIGATIONS TO THEIR CLIENTS............839 A. The Nature of the Literary Agent Profession ................ 839 B. Anthony v Morton ......................... 842 C. Friedman v. Kuczkir ........................ 848 D. Levin v. -

Client Connections – New York 2018 Clients Committed As of Thursday, May 03, 2018

Client Connections – New York 2018 Clients Committed as of Thursday, May 03, 2018 Please refrain from contacting these clients prior to the conference, as they will be less inclined to participate in our face-to-face programs if they're inundated with pitches. PLEASE NOTE: There will be NO same-day or same-week appointment signups. All lottery selections must be made during the Client Connections signup period: May 2 - 7, 2018. Client Connections is open to ASJA Professional Members ONLY. Want to become a Professional Member and participate in Client Connections? Visit http://asja.org/How-To-Join/Why-Join-ASJA and apply for Professional Membership for your chance to meet with these and more top editors. NOTE: You must apply for Professional Membership by April 16th and then, if accepted, join ASJA and pay in full by May 3rd. Company Category Online Publication Name Jameson Kowalczyk Company Name Sharecare We pay about $300 to start, though certain projects may pay more or Pay Range less. How freelancers are used We use freelancers primarily for content—articles and slideshows. We're looking for versatile, experienced consumer health and wellbeing writers who can reliably interpret studies, conduct interviews, report Desired Skills news, and research and source information for articles and slideshows. Candidates should ideally appreciate evidence-based science and keep an eye towards clickability, both for social media and email newsletters. Sharecare is a digital health and wellness engagement platform offering a range of health content (conditions, general wellness, public health, Additional info news, etc.) for an audience of engaged consumers.