The Mutual Dependency of Force and Law in American Foreign Policy Richard A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record of the Communications Policy & Research Forum 2009 in Its 2006 National Security Statement, George W

TWITTER FREE IRAN: AN EVALUATION OF TWITTER’S ROLE IN PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND INFORMATION OPERATIONS IN IRAN’S 2009 ELECTION CRISIS ALEX BURNS Faculty of Business and Law Victoria University [email protected] BEN ELTHAM Centre for Cultural Research University of Western Sydney and Fellow, Centre for Policy Development [email protected]) Abstract Social media platforms such as Twitter pose new challenges for decision-makers in an international crisis. We examine Twitter’s role during Iran’s 2009 election crisis using a comparative analysis of Twitter investors, US State Department diplomats, citizen activists and Iranian protestors and paramilitary forces. We code for key events during the election’s aftermath from 12 June to 5 August 2009, and evaluate Twitter. Foreign policy, international political economy and historical sociology frameworks provide a deeper context of how Twitter was used by different users for defensive information operations and public diplomacy. Those who believe Twitter and other social network technologies will enable ordinary people to seize power from repressive regimes should consider the fate of Iran’s protestors, some of whom paid for their enthusiastic adoption of Twitter with their lives. Keywords Twitter, foreign policy, international relations, United States, Iran, social networks 1. Research problem, study context and methods The next U.S. administration may well face an Iran again in turmoil. If so, we will be fortunate in not having an embassy in Tehran to worry about. From a safe distance, we can watch the Iranian people, again, fight for their freedom. We can pray that the clerical Gotterdamerung isn’t too bloody, and that the mullahs quickly retreat to their mosques and content themselves primarily with the joys of scholarly disputation. -

Furthermore, Religion Is Not a Set of Authoritarian Institutions of The

58 The Gulf and US National Security Strategy Lawrence Korb The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research This paper by Dr. Lawrence Korb, Senior Fellow, Center for American Progress, Washington DC, has been published in 2005 by The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research (ECSSR), P.O.Box 4567, Abu Dhabi, UAE as Emirates Lecture Series 58 (ISSN 1682-1238; ISBN 9948-00-728-X). It has been published with special permission from ECSSR. Copyright © belongs to The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research. All rights are reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this material, or any part thereof may not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. The Gulf and US National Security Strategy The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research (ECSSR) is an independent research institution dedicated to furthering scientific investigation of contemporary political, economic and social matters pertinent to the UAE, the Gulf and the Arab world. Since its establishment in 1994, the ECSSR has been at the forefront of analyses and commentary on emerging Arab affairs. The ECSSR invites prominent policy makers, academics and specialists to exchange ideas on a variety of international issues. The Emirates Lecture Series is the product of such scholarly discussions. Further information on the ECSSR can be accessed via its website: http://www.ecssr.ac.ae http://www.ecssr.com Editorial Board Aida Abdullah Al-Azdi, Editor-in-Chief Mary Abraham EMIRATES LECTURE SERIES – 58 – The Gulf and US National Security Strategy Lawrence Korb Published by The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research The Gulf and US National Security Strategy This publication is based on a lecture presented on June 6, 2004. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 0521673186 - The Right War?: The Conservative Debate on Iraq Edited by Gary Rosen Frontmatter More information THE RIGHT WAR? To declare oneself a conservative in American foreign policy is to enter imme- diately into a fractious, long-standing debate. Should America retreat from the world, deal with the world as it is, or try to transform it in its own image? Which school of thought – traditionalist, realist, or neoconservative – is truest to the country’s ideals and interests? With the dramatic shift in American foreign policy since 9/11, these dif- ferences have been brought into stark relief, especially by the Bush admin- istration’s decision to go to war in Iraq. This book brings together the most articulate and influential voices in the debate among conservatives over the tactics and strategy of America’s engagement in Iraq. Its contents run the gamut from protests to second thoughts to full-throated endorse- ments, and represent a vivid sampling of the ideological currents likely to influence the Bush administration as it tries to make good on its ambitious goals for Iraq and the wider Middle East. Gary Rosen is the managing editor of Commentary. A member of the Council on Foreign Relations, he holds a Ph.D. in political science from Harvard and is the author of American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding. His articles and reviews have appeared in Commentary, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University -

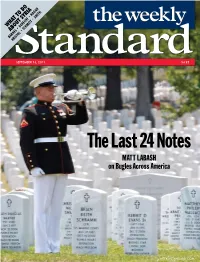

The Last 24 Notes MATT LABASH on Bugles Across America

WHAT TO DO ABOUT SYRIA BARNES • GERECHT • KAGAN KRISTOL • SCHMITT • SMITH SEPTEMBER 16, 2013 $4.95 The Last 24 Notes MATT LABASH on Bugles Across America WWEEKLYSTANDARD.COMEEKLYSTANDARD.COM Contents September 16, 2013 • Volume 19, Number 2 2 The Scrapbook We’ll take the disposable Post, the march of science, & more 5 Casual Joseph Bottum gets stuck in the land of honey 7 Editorial The Right Vote BY WILLIAM KRISTOL Articles 9 I Came, I Saw, I Skedaddled BY P. J. O’ROURKE Decisive moments in Barack Obama history 7 10 Do It for the Presidency BY GARY SCHMITT Congress, this time at least, shouldn’t say no to Obama 12 What to Do About Syria BY FREDERICK W. K AGAN Vital U.S. interests are at stake 14 Sorting Out the Opposition to Assad BY LEE SMITH They’re not all jihadist dead-enders 16 Hesitation, Delay, and Unreliability BY FRED BARNES Not the qualities one looks for in a war president 17 The Louisiana GOP Gains a Convert BY MICHAEL WARREN Elbert Lee Guillory, Cajun noir Features 20 The Last 24 Notes BY MATT LABASH Tom Day and the volunteer buglers who play ‘Taps’ at veterans’ funerals across America 26 The Muddle East BY REUEL MARC GERECHT Every idea Obama had about pacifying the Muslim world turned out to be wrong Books & Arts 9 30 Winston in Focus BY ANDREW ROBERTS A great man gets a second look 32 Indivisible Man BY EDWIN M. YODER JR. Albert Murray, 1916-2013 33 Classical Revival BY MARK FALCOFF Germany breaks from its past to embrace the past 36 Living in Vein BY JOSHUA GELERNTER Remember the man who invented modern medicine 37 With a Grain of Salt BY ELI LEHRER Who and what, exactly, is the chef du jour? 39 Still Small Voice BY JOHN PODHORETZ Sundance gives birth to yet another meh-sterpiece 20 40 Parody And in Russia, the sun revolves around us COVER: An honor guard bugler plays at the burial of U.S. -

Iraq Study Group Report

The Iraq Study Group Report James A. Baker, III, and Lee H. Hamilton, Co-Chairs Lawrence S. Eagleburger, Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Edwin Meese III, Sandra Day O’Connor, Leon E. Panetta, William J. Perry, Charles S. Robb, Alan K. Simpson Contents Letter from the Co-Chairs Executive Summary I. Assessment A. Assessment of the Current Situation in Iraq 1. Security 2. Politics 3. Economics 4. International Support 5. Conclusions B. Consequences of Continued Decline in Iraq C. Some Alternative Courses in Iraq 1. Precipitate Withdrawal 2. Staying the Course 3. More Troops for Iraq 4. Devolution to Three Regions D. Achieving Our Goals II. The Way Forward—A New Approach A. The External Approach: Building an International Consensus 1. The New Diplomatic Offensive 2. The Iraq International Support Group 3. Dealing with Iran and Syria 4. The Wider Regional Context B. The Internal Approach: Helping Iraqis Help Themselves 1. Performance on Milestones 2 2. National Reconciliation 3. Security and Military Forces 4. Police and Criminal Justice 5. The Oil Sector 6. U.S. Economic and Reconstruction Assistance 7. Budget Preparation, Presentation, and Review 8. U.S. Personnel 9. Intelligence Appendices Letter from the Sponsoring Organizations Iraq Study Group Plenary Sessions Iraq Study Group Consultations Expert Working Groups and Military Senior Advisor Panel The Iraq Study Group Iraq Study Group Support 3 Letter from the Co-Chairs There is no magic formula to solve the problems of Iraq. However, there are actions that can be taken to improve the situation and protect American interests. Many Americans are dissatisfied, not just with the situation in Iraq but with the state of our political debate regarding Iraq. -

Neo-Conservatism and Foreign Policy

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2009 Neo-conservatism and foreign policy Ted Boettner University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Boettner, Ted, "Neo-conservatism and foreign policy" (2009). Master's Theses and Capstones. 116. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neo-Conservatism and Foreign Policy BY TED BOETTNER BS, West Virginia University, 2002 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science September, 2009 UMI Number: 1472051 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI" UMI Microform 1472051 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

The Pentagon Muzzles the CIA | the American Prospect

The Pentagon Muzzles the CIA Devising bad intelligence to promote bad policy ROBERT DREYFUSS | December 16, 2002 Even as it prepares for war against Iraq, the Pentagon is already engaged on a second front: its war against the Central Intelligence Agency. The Pentagon is bringing relentless pressure to bear on the agency to produce intelligence reports more supportive of war with Iraq, according to former CIA officials. Key officials of the Department of Defense are also producing their own unverified intelligence reports to justify war. Much of the questionable information comes from Iraqi exiles long regarded with suspicion by CIA professionals. A parallel, ad hoc intelligence operation, in the office of Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Douglas J. Feith, collects the information from the exiles and scours other raw intelligence for useful tidbits to make the case for preemptive war. These morsels sometimes go directly to the president. The war over intelligence is a critical part of a broader offensive by the party of war within the Bush administration against virtually the entire expert Middle East establishment in the United States -- including State Department, Pentagon and CIA area specialists and leading military officers. Inside the foreign-policy, defense and intelligence agencies, nearly the whole rank and file, along with many senior officials, are opposed to invading Iraq. But because the less than two dozen neoconservatives leading the war party have the support of Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, they are able to marginalize that opposition. Morale inside the U.S. national-security apparatus is said to be low, with career staffers feeling intimidated and pressured to justify the push for war. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.Long.T65

Cambridge University Press 0521673186 - The Right War?: The Conservative Debate on Iraq Edited by Gary Rosen Table of Contents More information Contents List of Contributors ..............................page vii Introduction ..................................... 1 Gary Rosen 1 Iraq’s Future – and Ours .............................7 Victor Davis Hanson 2 The Right War for the Right Reasons ....................18 Robert Kagan and William Kristol 3 Iraq: Losing the American Way ........................36 James Kurth 4 Intervention With a Vision ...........................49 Henry A. Kissinger 5 An End to Illusion .................................54 The Editors of National Review 6 Quitters ........................................57 Andrew Sullivan 7 A More Humble Hawk; Crisis of Confidence ...............63 David Brooks 8 Time for Bush to See the Realities of Iraq .................67 George F. Will 9 Iraq May Survive, but the Dream Is Dead .................70 Fouad Ajami [v] © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521673186 - The Right War?: The Conservative Debate on Iraq Edited by Gary Rosen Table of Contents More information CONTENTS 10 The Perils of Hegemony .............................73 Owen Harries 11 Like It’s 1999: How We Could Have Done It Right ...........87 Fareed Zakaria 12 Reality Check – This Is War; In Modern Imperialism, U.S. Needs to Walk Softly ...........91 Max Boot 13 A Time for Reckoning: Ten Lessons to Take Away from Iraq ....96 Andrew J. Bacevich 14 World War IV: How It Started, What It Means, and Why We Have to Win ...........................102 Norman Podhoretz 15 The Neoconservative Moment ........................170 Francis Fukuyama 16 In Defense of Democratic Realism .....................186 Charles Krauthammer 17 ‘Stay the Course!’ Is Not Enough ......................201 Patrick J. Buchanan 18 Realism’s Shining Morality ..........................204 Robert F. -

Iraq: Next Phase in the Campaign?

Strategic Insight Iraq: Next Phase of the Campaign? by James Russell and Iliana Bravo Strategic Insights are authored monthly by analysts with the Center for Contemporary Conflict (CCC). The CCC is the research arm of the National Security Affairs Department at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Naval Postgraduate School, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. April 2, 2002 The Bush Administration's foreign policy is now being driven by a set of principles described by President Bush in his 2002 State of the Union Address. Characterized by various observers as the "Bush Doctrine," the outlines of this policy are: (1) that the United States will combat terror wherever it exists using all means at its disposal, including force; (2) that bilateral relationships around the world will be increasingly defined in terms of those countries that support the war on terrorism and those that do not; and (3) that "rogue" nations and/or terrorist organizations cannot be permitted to acquire and/or threaten the United States with weapons of mass destruction. President Bush identified three countries - Iran, Iraq and North Korea -- as the "axis of evil" and needing particular attention in the next phase of the war on terror. Subsequent remarks by the President and senior officials make clear that acting against Iraq and its brutal dictator Saddam Hussein are the focus in the next phase of implementing the Bush Doctrine around the globe.[1] Given the many policy pronouncements and press leaks over the last several months, there is a general impression that the issue is no longer whether Saddam will be attacked but when the attack will take place. -

2005Annual Report

2005Annual Report American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research BOARD OF TRUSTEES J. Joe Ricketts COUNCIL OF ACADEMIC Chairman and Founder ADVISERS Bruce Kovner, Chairman Ameritrade Holding Corporation Chairman James Q. Wilson, Chairman Caxton Associates, LLC Kevin B. Rollins Pepperdine University President and CEO Lee R. Raymond, Vice Chairman Dell Inc. Chairman and CEO Eliot A. Cohen Exxon Mobil Corporation John W. Rowe Professor and Director of Strategic Studies Tully M. Friedman, Treasurer Chairman, President, and CEO Chairman and CEO Exelon Corporation School of Advanced International Friedman Fleischer & Lowe LLC Studies Edward B. Rust Jr. Johns Hopkins University Gordon M. Binder Chairman and CEO Managing Director State Farm Insurance Companies Gertrude Himmelfarb Coastview Capital, LLC Distinguished Professor William S. Stavropoulos Harlan Crow Chairman of History Emeritus Chairman and CEO The Dow Chemical Company City University of New York Crow Holdings Wilson H. Taylor Samuel P. Huntington Christopher DeMuth Albert J. Weatherhead III President Chairman Emeritus American Enterprise Institute CIGNA Corporation University Professor of Government Harvard University Morton H. Fleischer Marilyn Ware Chairman Chairman Emerita William M. Landes Spirit Finance Corporation American Water Clifton R. Musser Professor of Law and Economics Christopher B. Galvin James Q. Wilson University of Chicago Law School Chairman Pepperdine University Harrison Street Capital, LLC Sam Peltzman Raymond V. Gilmartin Ralph and Dorothy Keller EMERITUS TRUSTEES Special Adviser to the Distinguished Service Professor Executive Committee Willard C. Butcher of Economics Merck & Co., Inc. Graduate School of Business Harvey Golub Richard B. Madden University of Chicago Chairman and CEO, Retired American Express Company Robert H. Malott Nelson W. -

The United States and Iran: a Dangerous but Contained Rivalry, by Mehran Kamrava

The Middle East Institute Policy Brief No. 9 March 2008 The United States and Iran: A Dangerous but Contained Contents Rivalry US Policy toward the Middle East 2 Washington’s “Iranian Threat” 4 By Mehran Kamrava Iranian Foreign Policy 8 Prospects for the Future 13 Executive Summary Despite dangerously high tensions between the United States and Iran, which are rooted in the fundamentally different foreign policy objectives of each country, the risks of open hostilities between the two sides are kept in check by the realization of the catastrophic consequences involved. The conflict be- tween the two sides is one of fundamental foreign policy visions and principles that often — especially since the start of President Bush’s second term — verge on the irreconcilable. The stakes of this dangerous rivalry are high, and the range of possible scenarios for moving beyond it is perilously limited. At the same time, however, both sides appear to be keenly aware of the catastrophic consequences of open hostilities between them, and thus seek to undermine the other’s interests without stepping beyond certain ill-defined red lines. High-level US-Iranian tensions are likely to continue for some time, therefore, without, however, spilling into open warfare. For more than 60 years, the Middle East Institute has been dedicated to increasing Americans’ knowledge and understanding of the re- gion. MEI offers programs, media outreach, language courses, scholars, a library, and an academic journal to help achieve its goals. About the Author The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in America and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and govern- ments of the region. -

N Ew S R Elease

e Media inquiries: Véronique Rodman s [email protected] 202.862.4870 a e l CHRISTOPHER DEMUTH TO RESIGN AS e AEI PRESIDENT IN 2008 R FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: October 11, 2007 s Christopher DeMuth, president of the American Enterprise Institute since 1986, will be stepping down from that position in 2008, the Institute’s Board of Trustees announced today. Mr. DeMuth conveyed w his decision to AEI’s trustees, scholars, and staff during the past week. He will remain at AEI as a senior e fellow, pursuing research and writing on American politics and society and his longtime specialty, govern- ment regulation. N Mr. DeMuth had this to say about his decision: “My twenty-one years as president of AEI have been thoroughly gratifying, edifying, and enjoyable. It has been a momentous period in American and international politics. Throughout, AEI’s scholars have made tremendous contributions to political discourse and to better government policy. AEI’s trustees, donors, and extended family have provided invaluable support—moral and intellectual as well as financial—to everything we have done. It has been a great privilege to work with them; I hope to continue to do so, in a new capacity, for many years to come. “Leadership successions are critical times for policy research institutes. That time will come sooner or later for AEI, and after careful thought I have concluded that the best time for us is now. Our finances are robust and our research and writing are deep, wide-ranging, and highly influential. We are in excellent stride to pass the baton to new leadership.