The Chemistry of Breadmaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

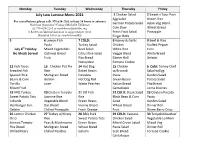

July Low Lactose Menu 2021

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 1 Chicken Salad 2 Sweet n’Sour Pork July Low Lactose Menu 2021 Egg Salad Brown Rice For cancellations, please call: 978-624-2263 at least 24 hours in advance Nutrition Questions? Contact Michelle Zelikman German Potato Salad Asian Veg Blend @ 978-624-2263 or [email protected] Cole Slaw Wheat Bread A $2.00 confidential donation is suggested per meal. Fresh Fruit Salad Pineapple Donation letters are mailed monthly Finger Rolls 5 6 Lemon Fish 7 COLD: 8 Honey & Garlic 9 Beef & Rice Pasta Turkey Salad Chicken Stuffed Pepper July 4th Holiday Mixed Vegetables Beet Salad White Rice Corn No Meals Served Oatmeal Bread Citrus Rice Salad Veggie Blend White Bread Fruit Pita Bread Dinner Roll Gelatin Honeydew Fortune Cookie 12 Fish Tacos 13 Chicken Pot Pie 14 Hot Dog 15 Chicken 6 Cold: Turkey Chef Breaded Fish Rice Baked Beans w/Broccoli Salad w/Egg Spanish Rice Multigrain Bread Coleslaw Pasta Garden Salad Beans & Corn Gelatin Hot Dog Roll Green Beans Potato Salad Tortilla Juice Warm Peaches Italian Bread Pita Bread Mixed Fruit Cantaloupe Lorna Doones 19 BBQ Turkey 20 Chicken Teriyaki 21 Dill Fish 22 COLD: Steak Salad 23 Chicken Piccata Sweet Potato Tots Jasmine Rice Rice Black Bean & Corn Pasta Collards Vegetable Blend Green Beans Salad Garden Salad Hamburger Bun Oat Bread Vienna Bread Wheat Bread Dinner Roll Gelatin Chilled Pineapple Fresh Orange Fruit Warm Berry Crisp 26 Lemon Chicken 27 Turkey w/Gravy 28 BBQ Pork 29 COLD: Caprese 30 Teriyaki Meatloaf Orzo Rice Sweet Potato Tots Chicken Salad Vegetable Lo Mein Stewed Tomato Peas & Mushrooms Green Beans Mixed Green Salad Mixed Veg Pita Bread Multigrain Bread Wheat Bread Pasta Salad Dinner Roll Chilled Pears Chilled Peaches Gelatin Scali Bread Fortune Cookie Cantaloupe . -

Weekly Sales a New Deal Every Day! Your Trusted, Local Grocer

Prices valid Wed, 5/2 - Tue, 5/8 - Page 1 DAILY DEALS Weekly Sales A new deal every day! Your trusted, local grocer. Wednesday may 2nd May 2nd - May 8th | sendiks.com/weeklyad Cut Watermelon ¢ lb 29 Limit 10lbs Sendik’s Natural NATURAL ocessed Thursday • Minimally Pr , Never Frozen • t of USA Fresh ents Produc may 3rd No Artificial Ingredi Boneless Pork Chops or Roasts Kemps Select 2%, 1% and Skim Milk Value Pack $ 99 1 gallon Limit 2 99 99 2 lb Friday lb may 4th 2 Sendik’s Premium NATURAL Sendik’s Natural rocessed • inimally P North Atlantic M USA Fresh, Never Frozen • Product of Haddock Loins No Artificial Ingredients USDA Choice Black Angus $ 99 Rump Roast 3 lb Limit 10 lbs Premium Frozen NATURAL Sendik’s Saturday • Minimally Processed Fresh, Never Frozen • Product of USA may 5th No Artificial Ingredients Natural USDA North Atlantic Haddock Loins Sendik’s Pasture Premium Pasture Premium 100% Grass-Fed Ground Beef 100% Grass Fed 99 $ 99 Boneless Rib Eye 4 lb lb 3 Limit 6 lbs Steaks Sunday may 6th 99 ¢ Sendik’s Homemade 12lb 59lb Organicgirl Gourmet Beef or Turkey Burgers Salads Assorted Varieties Fi rst of the Season! 50/50 Blend, Baby $ 99 Vidalia Sweet Onions Arugula, Baby Spinach, 3 lb Limit 6 lbs Baby Spinach & Arugula Monday Sendik’s Premium may 7th Raised in Romsdal Region of Norway Farm Raised $ Sendik’s Antibiotic Free 35 oz Amish BAP Certifi ed Norwegian Steelhead Rotisserie Chicken Chain of Custody Traceability $ Salmon Fillets 5 ea Limit 2 Fresh, Never Frozen. No antibiotics - ever Tuesday may 8th 99 No added hormones lb Vegetable -

Commercial Breads

Grains of truth about COMMERCIAL BREADS Definitions Nutritional value Bread, called the staff of life, differs greatly in All breads are nutritious—some more so than size, shape, texture, appearance, and flavor. Yeast others. The 2005 edition of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines breads come in a variety of shapes, including for Americans recommends enjoying five to ten flatbreads such as pita or focaccia, buns, rolls and ounces daily of bread, cereal, rice and pasta loaves in the form of hearth or pan breads. (depending on age, gender and activity level) – with half coming from whole grains. They are a major Pan breads: These can be made from white source of complex carbohydrates (starches), fiber, iron flour, whole wheat, or a combination of flours. They and B vitamins and are generally low in fat. are baked in loaf pans for a softer crust. Pan breads may include coarse-textured home-style, richer Keep in mind that serving sizes are equal to premium, and buttery split-top breads. one-ounce and therefore relatively small. One slice of bread weighing one-ounce is a serving, so a sandwich Hearth breads: Baked directly on the hearth would provide two servings. for crispier crusts, some white hearth breads include French, Italian and Vienna bread. The dietary guideline also recommends at Whole wheat bread: This bread is made least 45 to 65 percent of daily calories come from entirely from whole grain wheat flour, which contains carbohydrates, 20 to 35 percent from fat and 10 to 35 all the components of the wheat kernel—the germ, percent from protein. -

Prominent and Progressive Americans

PROMINENTND A PROGRESSIVE AMERICANS AN ENCYCLOPEDIA O F CONTEMPORANEOUS BIOGRAPHY COMPILED B Y MITCHELL C. HARRISON VOLUME I NEW Y ORK TRIBUNE 1902 THEEW N YORK public l h:::ary 2532861S ASTIMI. l .;-M':< AND TILI'EN ! -'.. VDAT.ON8 R 1 P43 I Copyright, 1 902, by Thb Tribune Association Thee D Vinne Prem CONTENTS PAGE Frederick T hompson Adams 1 John G iraud Agar 3 Charles H enry Aldrich 5 Russell A lexander Alger 7 Samuel W aters Allerton 10 Daniel P uller Appleton 15 John J acob Astor 17 Benjamin F rankldi Ayer 23 Henry C linton Backus 25 William T . Baker 29 Joseph C lark Baldwin 32 John R abick Bennett 34 Samuel A ustin Besson 36 H.. S Black 38 Frank S tuart Bond 40 Matthew C haloner Durfee Borden 42 Thomas M urphy Boyd 44 Alonzo N orman Burbank 46 Patrick C alhoun 48 Arthur J ohn Caton 53 Benjamin P ierce Cheney 55 Richard F loyd Clarke 58 Isaac H allowell Clothier 60 Samuel P omeroy Colt 65 Russell H ermann Conwell 67 Arthur C oppell 70 Charles C ounselman 72 Thomas C ruse 74 John C udahy 77 Marcus D aly 79 Chauncey M itchell Depew 82 Guy P helps Dodge 85 Thomas D olan 87 Loren N oxon Downs 97 Anthony J oseph Drexel 99 Harrison I rwln Drummond 102 CONTENTS PAGE John F airfield Dryden 105 Hipolito D umois 107 Charles W arren Fairbanks 109 Frederick T ysoe Fearey Ill John S cott Ferguson 113 Lucius G eorge Fisher 115 Charles F leischmann 118 Julius F leischmann 121 Charles N ewell Fowler ' 124 Joseph. -

2019 Product Catalog

Food AND household essentials shopped AND delivered to meet your independent living needs Store to Door Services 2019 Product Catalog PRODUCT CATALOG In your Store-To-Door 2019 Product Catalog, you will find thousands of grocery items listed in a conveniently-organized, easy-to-use list. This catalog will: • Help you keep track of what items you need between ordering days • Help maintain a list of products you order regularly • Allow you and your order taker to work from the same list when ordering over the phone. You will continue to automatically receive coupon and sale prices on items in the catalog. If items are out of stock, you can indicate whether you want your shopper to substitute similar items of equal or lower price. Please check with your order taker for monthly specials that may be available. NETWORK OF SERVICES GROCERY ASSISTANCE TRANSPORTATION HOME SUPPORT Our service provides access We can take you to Need a little help around the to nutrition, personal appointments and house? Offering both chore contact, and helpful hand anywhere else within the assistance and home repair, in your kitchen. seven counties we serve. we can help keep your home orderly inside and out. Service includes: • Do you have a list of • Phone order placement errands to run? No Examples: dusting, washing • Shopping and delivery of problem. We can make windows, cleaning counters, groceries multiple stops and wait organizing areas, repairing • Help with the extras: for you. drywall, hanging decor, unpacking bags, putting • Want a friend to come moving help, painting walls, heavy items away and along? Rides can be and more! more! accompanied. -

Breads How Can We Sweeten Your Day Breads

Breads How can we sweeten your day Breads Multi-GrainMulti-Grain LoafLoaf bread made made with with flour flour from fromsix different six different types of typesgrain: wheat,of grain: rye, oat,wheat, barley, rye, millet, oat, and corn. barley,It is a hearty millet, and andheavy corn. bread It with is a seeds hearty and and grain heavy parts mixed bread throughout. with seeds and grain parts mixed throughout. Vienna ViennaOur white bread offered with sesame seeds, poppy seeds or plain. A yeast bread that has a thin, Ourcrispy white crust breadthat has offered a glazed appearancewith sesame and seeds,is a light, poppy airy bread. seeds This or bread plain. has A ayeast very unique bread thatcrust, has in part a thin, because crispy of the crust baking that process, has a whichglazed includes appearance steam heat and as isopposed a light, to airy entirely bread. dry Thisheat, bread which mosthas abread very is unique baked in. crust, in part because of the baking process, which includes steam heat as opposed to entirely dry heat, which most bread is baked in. RyeRye BreadBread AA medium medium rye rye bread bread offered offered with carawaywith caraway seeds or seedsplain. Madeor plain. with flourMade from with the flour rye grain from and Caraway thepowdered rye grain caraway and seasoning. powdered caraway seasoning. Seeds SourSour DoughDough Hard-crustedHard-crusted white white bread bread made made from a fromsoured a sponge. soured This sponge. bread must This sit bread and ferment must tosit achieve and fermentit’s taste and to achievetexture. it’s taste and texture. -

US V. Gonnella Baking Co. and Torino Baking

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS - EASTERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, )Civil Action No. 72 C 2484 ) v. ) )Equitable Relief Sought GONNELLA BAKING CO.; and ) TOR1NO BAKING CO., ) )Filed: October 4, 1972 Defendants. ) COMPLAINT The United States of America, plaintiff, by its attorneys, acting under the direction of the Attorney General of the United States, brings this civil action against the defendants named herein, and complains and alleges as follows: JURISDICTION AND VENUE 1. This complaint is filed and this action is instituted under Section 4 of the Act of Congress of July 2, 1890, as amended (15 U.S.C. S 4), commonly known as the Sherman Act, in order to prevent and restrain continuing violation by the defendants, as hereinafter alleged, of Section 1 of said Act (15 U.S.C. § 1). 2. Each of the defendants transactsbusiness and is found in the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division. II THE DEFENDANTS 3. Gonnella Baking Co. (hereinafter referred to as "Gonnella") is hereby made a defendant herein. Gonnella is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of Illinois, with its principal place of business at Chicago, Illinois. Gonnella and .its wholly-owned sub- sidiary, United Bakeries, Inc., are engaged in baking and selling Italian, French and Vienna bread in the greater Chicago area. 4. Torino Baking Co. (hereinafter referred to as "Torino") is hereby made a defendant herein. Torino is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of Illinois, with its principal place of business at Chicago, Illinois. -

ALASKA SOURDOUGH: BREAD, BEARDS and YEAST by Susannah T. Dowds, B.A. a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiremen

Alaska sourdough: bread, beards and yeast Item Type Thesis Authors Dowds, Susannah T. Download date 01/10/2021 03:33:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/7874 ALASKA SOURDOUGH: BREAD, BEARDS AND YEAST By Susannah T. Dowds, B.A. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of the Arts in Northern Studies University of Alaska Fairbanks August 2017 APPROVED: Terrence Cole, Committee Chair Mary Ehrlander, Committee Member Director of Arctic and Northern Studies Molly Lee, Committee Member Todd Sherman Dean of the College of Liberal Arts Michael Castellini Dean of the Graduate School Abstract Sourdough is a fermented mixture of flour and water used around the world to leaven dough. In this doughy world wide web of sourdough, one thread leads to Alaska and the Yukon Territory. Commonly associated with the gold rush era, sourdough is known both as a pioneer food and as a title for a long-time resident. Less well known is the live culture of microbes, yeasts and bacteria that were responsible for creating the ferment for nutritious bread, pancakes, and biscuits on the trail. Through the lens of sourdough, this study investigates the intersection of microbes and human culture: how microbes contribute taste and texture to baked goods; why sourdough, made from imported ingredients, became a traditional food in the North; and how “Sourdough” grew to signify an experienced northerner. A review of research about sourdough microflora, coupled with excerpts from archival sources, illuminates how human and microbial cultures intertwined to make sourdough an everyday food in isolated communities and mining camps. -

Of Pita Bread

SHELF-LIFE EXTENSION STUDIES ON PITA BREAD Aniss Adib El-Khoury Department of Food Science and Agricultural Chemistry Macdonald Campus McGill University Montreal, Quebec Canada A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfiilment of the requirements of degree of Master of Science March, 1999 @ Anis Aàib El-Khoury National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OiiawaON K1AW OitawaON K1AON4 Ceneda Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aliowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/£iim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celeci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. aut onsation. My father, Adib, my mother, Aida, my sister, Sumaya, my brother, Raji God, the Giver of al1 the Blessing A bstract Shelf-Life Extension Studies on Pita Bread In this research, three alternative approaches to chemical preservatives to extend the mold free shelf-life and quality of pita bread were investigated namely: Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP) involving gas packaging, oxygen absorbents technology and ethanol vapor generators, high pressures, and direct and indirect heating. -

2016 Kansas Statutes

2016 Kansas Statutes 65-2301. Definitions. When used in this act: (a) The term "flour" includes and shall be limited to the foods defined as (1) flour, white flour, wheat flour, plain flour, (2) bromated flour, (3) self-rising flour, self-rising white flour, self-rising wheat flour, and (4) phosphated flour, phosphated white flour, and phosphated wheat flour but excludes whole wheat flour and also excludes special flours not used for bread, roll, bun or biscuit baking, such as specialty cake, pancake and pastry flours in the definitions and standards of identity and quality adopted and published by the secretary of health and environment under the authority vested in the secretary by the Kansas food, drug and cosmetic act. (b) The term "enriched" as applied to flour, means the addition to flour of the vitamins and minerals necessary to make it conform to definition and standard of identity of enriched flour, enriched bromated flour, enriched self-rising flour or enriched phosphated flour, as the case may be as fixed and established by the secretary of health and environment under authority vested in the secretary by the general food and drug acts, such standards to be identical with those established by the proper federal agency under the federal food, drug, and cosmetic act of 1938, unless in the opinion of the secretary changes made in the federal standards subsequent to the effective date of this act will not serve the best interests of the citizens of the state of Kansas or are oppressive to the milling and baking industries of the state. -

Exposure Estimate for Semicarbazide from the Use of Azodicarbonamide in Bread for the U.S. Population S

Exposure Estimate for Semicarbazide from the Use of Azodicarbonamide in Bread for the U.S. Population S. Bhagan, D. Doell, H. Lee, T. Croce, and S. Carberry U.S. Food and Drug Administration, College Park, MD 20740 Introduction Identification of Bread Products Method of Estimating Exposure Results Analytical Data Containing ADA as an Ingredient Azodicarbonamide (ADA) is approved for use (21 CFR 172.806): Dietary exposure estimates for SEM from the use of ADA in bread and bread products Table 1: Eaters-only Exposure to SEM (μg/p/d) for the U.S. Population Aged 2 Years and Older Based on 2009-2012 Table 3: Eaters-only Exposure to SEM (μg/p/d) for Children Aged 2-5 Years Based on 2009-2012 NHANES 2-Day Food Table 5: Range of SEM Analytical Results (μg/kg) for Bread and Bread Products Considered in the Exposure Estimate were performed using two different sets of food consumption data: 1) the combined NHANES 2- Day Food Consumption Data. Consumption Data. Bagels <5 - 117 Submarine Rolls 35 - 1260 • As an aging and bleaching ingredient in cereal flour in an amount not to exceed Two different sources were used to identify bread products labeled as containing ADA: 2009-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2-day Low Exposure Average Exposure High Exposure Low Exposure Average Exposure High Exposure Biscuits <5 - 767 Wheat Breads <5 - 191 2.05 grams per 100 pounds of flour (0.0045 percent; 45 parts per million). dietary intake survey; and 2) the 2007-2010 NPD Group, Inc. National Eating Scenario Scenario Scenario Scenario -

(Adapted from the Bread Bakers Apprentice) Pate Fermentee (Made the Day Before) 185G Pate Fermente

http://bewitchingkitchen.com VIENNA BREAD WITH DUTCH CRUMB (adapted from The Bread Bakers Apprentice) Pate fermentee (made the day before) 140 g bread flour 2.5 g salt 1/2 teaspoon instant yeast and 100 g water at room temperature Mix all ingredients, knead briefly and let it rise at room temperature for 1 to 2 hours. Place the mixture in the fridge overnight, remove from the fridge one hour before making the bread. Dough: 185g pate fermentee (you will not use the full amount made) 170g unbleached bread flour 7g sugar 4.5g salt 2g instant yeast (3/4 tsp) 1/2 egg, slightly beaten 7g unsalted butter, melted and slightly cooled 85-100 ml water, lukewarm (90 – 100 F) Dutch Crumb Paste: 1 Tbs bread flour 3/4 cup rice flour 3/4 tsp. instant yeast 2 tsp. sugar 1/4 tsp. salt 2 tsp oil 8 tbsp water (or a little more) to make a thick paste. Remove the pate fermentee from the refrigerator, cut it into 5-6 small pieces, cover and let it at room temperature for about 1 hour. Stir together the flour, sugar, salt, and yeast in a large bowl. Add the pate fermentee pieces, the beaten half egg, butter, and 85 ml of the water. Stir together with a large metal spoon, or with your hands, until the ingredients form a ball. If too dry, add the rest of the water (I did). Let it rest for 20 minutes. Knead by folding 3 times at 20 minutes intervals. At the end of the third cycle of folding (at 1 hour fermentation), leave the dough covered, undisturbed, for another hour.