Readers' Real-Life Narratives in Selected Contemporary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution List Page - 1

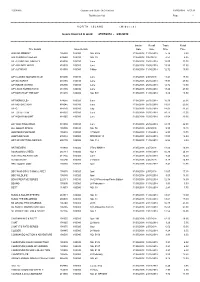

R56891A Gordon and Gotch (NZ) Limited 29/05/2018 8:57:12 Distribution List Page - 1 =========================================================================================================================================================== N O R T H I S L A N D ( M i d w e e k ) Issues invoiced in week 27/05/2018 - 2/06/2018 =========================================================================================================================================================== Invoice Recall Trade Retail Title Details Issue Details Date Date Price Price 2000 AD WEEKLY 105030 100080 NO. 2075 31/05/2018 11/06/2018 5.74 8.80 500 SUDOKU PUZZLES 239580 100010 NO. 39 31/05/2018 9/07/2018 4.53 6.95 A/F AEROPLANE MNTHLY 818005 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 15.00 23.00 A/F AIRLINER WRLD 818020 100020 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 15.59 23.90 A/F AUTOCAR 818030 100080 9 May 31/05/2018 11/06/2018 12.72 19.50 A/F CLASSIC MOTORCYCLE 915600 100010 June 31/05/2018 2/07/2018 11.41 17.50 A/F GUITARIST 818155 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 17.93 27.50 A/F INSIDE UNITED 896390 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 12.72 19.50 A/F LINUX FORMAT DVD 818185 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 18.20 27.90 A/F MATCH OF THE DAY 818215 100080 NO. 504 31/05/2018 11/06/2018 8.80 13.50 A/F MONOCLE> 874655 100020 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 16.30 25.00 A/F MOTORSPORT 818245 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 13.63 20.90 A/F Q 818270 100010 July 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 14.02 21.50 A/F TOTAL FILM 818335 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 10.11 15.50 A/F WOMAN&HOME 818365 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 13.04 20.00 A/F YACHTING WRLD 818380 100010 June 31/05/2018 25/06/2018 14.35 22.00 ALL ABOUT SPACE 105505 100010 NO. -

ABC Consumer Magazine Concurrent Release - Dec 2007 This Page Is Intentionally Blank Section 1

December 2007 Industry agreed measurement CONSUMER MAGAZINES CONCURRENT RELEASE This page is intentionally blank Contents Section Contents Page No 01 ABC Top 100 Actively Purchased Magazines (UK/RoI) 05 02 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 09 03 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution (UK/RoI) 13 04 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Circulation/Distribution Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 17 05 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Actively Purchased Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 21 06 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Newstrade and Single Copy Sales (UK/RoI) 25 07 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Single Copy Subscription Sales (UK/RoI) 29 08 ABC Market Sectors - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 33 09 ABC Market Sectors - Percentage Change 37 10 ABC Trend Data - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution by title within Market Sector 41 11 ABC Market Sector Circulation/Distribution Analysis 61 12 ABC Publishers and their Publications 93 13 ABC Alphabetical Title Listing 115 14 ABC Group Certificates Ranked by Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 131 15 ABC Group Certificates and their Components 133 16 ABC Debut Titles 139 17 ABC Issue Variance Report 143 Notes Magazines Included in this Report Inclusion in this report is optional and includes those magazines which have submitted their circulation/distribution figures by the deadline. Circulation/Distribution In this report no distinction is made between Circulation and Distribution in tables which include a Total Average Net figure. Where the Monitored Free Distribution element of a title’s claimed certified copies is more than 80% of the Total Average Net, a Certificate of Distribution has been issued. -

Disabled People As Football Fans Introduction

Durham E-Theses Supporting the Fans: Learning-disability, Football Fandom and Social Exclusion SOUTHBY, KRIS How to cite: SOUTHBY, KRIS (2013) Supporting the Fans: Learning-disability, Football Fandom and Social Exclusion, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7004/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Kris Southby Supporting the Fans: Learning-disability, Football Fandom and Social Exclusion In Britain, within the contemporary drive of using sport to tackle the isolation of socially excluded groups, association football (football) fandom has been implicated in many policy documents as a possible site for learning-disabled people to become more socially included. However, whilst there is some evidence of the benefits of playing football for learning-disabled people, there is little evidence to support these claims. Drawing on empirical data from learning-disabled people about their experiences of football fandom and from relevant authorities responsible for facilitating the fandom of learning-disabled people, this thesis provides a critical analysis of the opportunities to tackle social exclusion that football fandom provides learning-disabled people. -

Developments in Federal Search and Seizure Law

FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER DISTRICT OF OREGON LISA C. HAY Federal Public Defender Oliver W. Loewy STEPHEN R. SADY 101 SW Main Street, Suite 1700 Elizabeth G. Daily Chief Deputy Defender Portland, OR 97204 Conor Huseby Gerald M. Needham Robert Hamilton Thomas J. Hester 503-326-2123 / Fax: 503-326-5524 Bryan Francesconi Ruben L. Iñiguez Ryan Costello Anthony D. Bornstein Branch Offices: Irina Hughes▲ Susan Russell Kurt D. Hermansen▲ Francesca Freccero 859 Willamette Street 15 Newtown Street Devin Huseby + C. Renée Manes Suite 200 Medford, OR 97501 Kimberly-Claire E. Seymour▲ Nell Brown Eugene, OR 97401 541-776-3630 Jessica Snyder Kristina Hellman 541-465-6937 Fax: 541-776-3624 Cassidy R. Rice Fidel Cassino-DuCloux Fax: 541-465-6975 Alison M. Clark In Memoriam Brian Butler + Nancy Bergeson Thomas E. Price 1951 – 2009 Michelle Sweet Mark Ahlemeyer ▲ Eugene Office Susan Wilk + Medford Office Research /Writing Attorney DEVELOPMENTS IN FEDERAL SEARCH AND SEIZURE LAW Stephen R. Sady Chief Deputy Federal Public Defender October 2020 Update Madeleine Rogers Law Clerk TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 B. What Constitutes A Search? ............................................................................................ 3 C. What Constitutes A Seizure? ......................................................................................... 14 D. Reasonable Expectation of Privacy .............................................................................. -

03 Prenumerata 2010.Indd

Ośrodek Szkoleniowo -Integracyjny Kolportera w Smardzewicach nad Zalewem Sulejowskim Ośrodek Szkoleniowo-Integracyjny Kolportera w Smardzewicach k/Tomaszowa Mazowieckiego, nad Zalewem Sulejowskim to idealne miejsce do przeprowadzenia wszelkiego rodzaju szkoleń, konferencji, seminariów, imprez integracyjnych, wczasów i rodzinnych imprez okolicznościowych. nasze atuty Dysponujemy zapleczem szkoleniowym i komfortową bazą hotelową. Naszym głównym atutem jest niepowtarzalna, domowa kuchnia! Pobyt naszym gościom umila profesjonalna obsługa. wspaniała okolica Malownicze jezioro, sosnowe lasy, cisza, krystalicznie czyste powietrze, tworzą znakomite warunki do nauki i wypoczynku. dogodna lokalizacja - Tomaszów Mazowiecki 7 km - Łódź – 57 km - Warszawa – 117 km - Katowice – 170 km 97-213 Smardzewice, ul. Klonowa 14 Zapraszamy tel. (+4844) 710 86 81, 510 031 715 e-mail: [email protected] Szanowni Państwo! Historia Kolportera zaczęła się przed 20 laty – w maju 1990 r., od powstania Przedsiębiorstwa Wielobranżowego – Zakładu Kolportażu Książki i Prasy „Kolporter”. W ciągu kilku lat stworzyliśmy jedną z najbardziej dynamicznych organizacji gospodarczych w Polsce – grupę kapitałową, która dzięki profilowi działalności wchodzących w jej skład spółek zapewnia kompleksową obsługę nie tylko dużych firm i sieci handlowych, lecz także pojedynczych punktów sprzedaży detalicznej. W skład Grupy Kapitałowej Kolporter wchodzą: Kolporter DP – największy i najbardziej dynamiczny dystrybutor prasy i książek, posiada 17 oddziałów terenowych zlokalizowanych w największych miastach wojewódzkich i powiatowych. Firma obsługuje ponad 49% rynku dystrybucji prasy, rozprowadza około 5000 tytułów polskich i zagranicznych do ponad 27 tysięcy punktów sprzedaży detalicznej i 12.000 prenumeratorów – firm, banków, urzędów, przedsiębiorstw, instytucji państwowych i samorządowych. Grzegorz Fibakiewicz Firma kurierska K-EX (dawniej Kolporter Express) świadczy usługi kurierskie Prezes Zarządu Kolportera DP Sp. z o.o. dla firm i instytucji. -

Public Sa P Afety Vid Proposal Deo and L for Coo D Vehicle Operativ E

RFP# OOK-MA-145 Due: Monday, July 11th, 2016 at 3:00 pm Proposal for Cooperative Contract for Public Safety Video and Vehicle Mounted Equipment NASPO ValuePoint Submitted by WatchGuard Video WatchGuard Video 415 Century Parkway, Allen, TX 75013 1.800.MPEG (6734) www.watchguardvideo.com This page was intentionally left blank for the purpose of double-sided printing. 8th of July, 2016 OMES / Central Purchasing 5005 North Lincoln Boulevard Suite 300 Oklahoma City, OK 73105 Reference: Solicitation # OK‐MA‐145 NASPO ValuePoint Cooperative Contract for Public Safety Video Systems and Vehicle Mounted Equipment WatchGuard Video is pleased to present the 4RE HD Wireless In‐Car Video System and the VISTA Body Worn Camera System to the State of Oklahoma and NASPO ValuePoint Cooperative Purchasing Program in response to Solicitation# OK‐MA‐145. We are the manufacturer and supplier of the products being offered in this proposal. Our legal company name is Enforcement Video, LLC, but we request that NASPO Value Point Cooperative Purchasing Program refer to and list us using our D.B.A. WatchGuard Video. We agree to the Master Agreement Terms and Conditions as written in Attachment A of the Request for Proposal. Thank you for your consideration to this proposal. Respectfully Submitted, Kyrie Endres Proposal Manager Contact Information: Primary Point of Contact Kyrie Endres, Proposal Manager (214) 785‐2608 ‐ Direct [email protected] ‐ Email Company WatchGuard Video 415 Century Parkway Allen, TX 75013 (800) 605‐6734 – Toll Free (972) 423‐9777 – Main -

Revving up the Deportation Machinery: Enforcement and Pushback Under Trump

REVVING UP THE DEPORTATION MACHINERY Enforcement and Pushback under Trump By Randy Capps, Muzaffar Chishti, Julia Gelatt, Jessica Bolter, and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto REVVING UP THE DEPORTATION MACHINERY Enforcement and Pushback under Trump By Randy Capps, Muzaffar Chishti, Julia Gelatt, Jessica Bolter, and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto May 2018 Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for contributing to the research for this report. ICE leaders in Washington, DC, and staff at seven field offices gave generously of their time, experience, and expertise. They also responded to Migration Policy Institute (MPI) Freedom of Information Act data requests in a timely fashion, and ICE experts met with MPI researchers to help them better understand the data. Thanks also go to the more than 120 elected officials, law enforcement officials, immigrant service providers, immigration defense attorneys, former immigration judges, community leaders, community organizers, and advocates who met with MPI researchers across the study sites. They shared generously of their time in describing their work and responses to urgent new needs they face in carrying out their varied missions. The authors are grateful too for the cooperation and interviews they were able to have with the networks of Mexican, Honduran, and Salvadoran consulates that are assisting their nationals in communities around the United States. The authors appreciate the time that three external immigration policy experts devoted to reviewing and giving comments on the first draft of the report, as well as that of MPI colleagues Michael Fix, Doris Meissner, and Mark Greenberg, who provided advice throughout the research and writing and served as internal reviewers. -

Macao Public Library - Periodicals from Foreign Countries 2018

Macao Public Library - Periodicals from Foreign Countries 2018 Wong Wong Wong Wong Ieng Ieng Kuan Ieng Kuan Ieng Kuan Wong Macao Library in Red Sir Robert Kuan Library in Children's Patane S. Louren Ilha Verde Mong Há Library in Taipa Ieng Kuan Coloane Central Ho Yin Market Ho Tung Library Areia Library in Total Publishi Library ço ibrary Library Library Luis de Library Library in Library Library Garden Library Library in Dr. Sun Preta Areia Number No. Title ng Camões Taipa Yat Sen Urban Preta of Cycle Garden Municipal Park Urban Copies Number Number Number Number Number Number Number Number NumberPark Number Number NumberPark Number Number Number of of of of of of of of of of of of of of of Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies Copies 1 A+U Monthly 1 1 1 3 2 AQUA LIFE Monthly 1 1 3 Art Review (U.K版) Monthly 1 1 4 assistant Quarterly 1 1 1 1 1 5 5 Astronomy (U.S版) Monthly 1 1 1 3 6 Automobile (U.S版) Monthly 1 1 1 1 4 7 BASS PLAYER Monthly 1 1 2 8 BBC GoodFood (U.K版) Monthly 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 9 BBC MUSIC (U.K 版) 13/yr 1 1 1 1 4 10 Bead Sty1e(U.S版) Bi-monthly 1 1 1 1 4 Better Homes & 11 Monthly 1 1 1 1 1 5 Gardens (U.S版) 12 Bike Magazine (U.K版) Monthly 1 1 1 3 Black Belt Magazine 13 Bi-monthly 1 1 1 3 (U.S版) 14 Bloomberg Business WeekWeekly (U.S 版)1 1 1 3 15 Bridal Guide (U.S版) Bi-monthly 1 1 1 1 4 Combat Aircraft (The 16 International Journal of Monthly 1 1 1 3 Military Aviation) (U.K版) 17 Country Living (U.S版) Monthly 1 1 1 1 4 18 Crafts Beautiful Monthly 1 1 2 19 Creative Review(U.K版) -

400/230 Volt 60Hz UPS Power

400/230 Volt 60Hz UPS Power Using Dual Voltage standby generation and UPS in one Nothing protects quite like Piller www.piller.com Contents 1 Abstract..........................................................................................................................3 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................4 3 Alternative Power Distribution .....................................................................................6 4 Integrating UPS in a 400 V 60 Hz distribution..............................................................8 5 Supplying Essential Loads in a 400 V distribution ...................................................10 6 Integrated power supply of Critical and Essential loads..........................................13 7 Summary......................................................................................................................15 8 References...................................................................................................................16 2 1 Abstract Within data centers the power used for operating the facility, running IT loads and cooling is the largest expense. With power densities continuing to rise, overall efficiency is still a major issue especially as power cost increases as well. The more the power density per rack raises the more floor space needs to be allocated for power supply components like PDUs, breakers and cabling. The power distribution through the building to the IT -

Essay a FRESH LOOK at TESTS for NONLITERAL COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT

Copyright 2013 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. Northwestern University Law Review Vol. 107, No. 4 Essay A FRESH LOOK AT TESTS FOR NONLITERAL COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT Pamela Samuelson ABSTRACT-Determining whether a copyright has been infringed is often straightforward in cases involving verbatim copying or slavish imitation. But when there are no literal similarities between the works at issue, ruling on infringement claims becomes more difficult. The Second and Ninth Circuits have developed five similar yet distinct tests for judging nonliteral copyright infringement. This Essay argues that each of these tests is flawed and that courts have generally failed to provide clear guidance about which test to apply in which kinds of cases. This Essay offers seven specific strategies to improve the analysis of nonliteral infringements. Courts should do more, for instance, to tailor infringement analysis based on the nature of the works at issue (that is, are they fanciful or artistic works or are they factual or functional?). The goal of this Essay is to offer these strategies as a way to bring greater coherence and consistency to the determination of nonliteral infringements, and to do so in a manner that properly balances the interests of first and subsequent generations of creators. AUTHOR-Richard M. Sherman Distinguished Professor, Berkeley Law School. I am grateful to Northwestern University School of Law for the opportunity to deliver the Julius Rosenthal Lectures, from which this Essay derives, and to Kathryn Hashimoto for her invaluable contributions to this Essay. I am also grateful for comments on an earlier draft by Julie Cohen, Paul Geller, Daniel Gervais, Paul Goldstein, Neil Netanel, David Nimmer, Christopher Sprigman, Rebecca Tushnet, and Molly Van Houweling. -

Bruce Springsteen 1

i i Bruce Springsteen 1 www.americanradiohistory.com THE MUSIC SOLUTION WARNER ELEKTBA ATLANTIC Warner Bros. Records Elektra Records Atlantic Records WEA Distributing Divisions of Warner Communications Inc... www.americanradiohistory.com VOLUME XLIII - NUMBER 32 - December 26, 1981 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY COSH BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher NICK ALBARANO Vice President ALAN SUTTON Vice President and Editor In Chief J.B. CARMICLE Vice President and General Manager, East Coast JIM SHARP Vice President, Nashville RICHARD IMAMURA Managing Editor MARK ALBERT caon' Marketing Director East Coast Editorial FRED GOODMAN - DAVE SCHULPS LARRY RIGGS West Coast Editorial MARK ALBERT. Radio Editor MARC CETNER - MICHAEL GLYNN MICHAEL MARTINEZ rccttng5 Research KEN KIRKWOOD, Manager BILL FEASTER - LEN CHODOSH MIKE PLACHETKA - JEFF LAINE be yours today HARALD TAUBENREUTHER May the Peace and Joy of the Holiday Season and in the coming year. Nashville Editorial/Research JENNIFER BOHLER, Nashville Editor JUANITA BUTLER - TIM STICHNOTH TOM ROLAND Art Director LARRY CRAYCRAFT Circulation THERESA TORTOSA, Manager PUBLICATION OFFICES NEWS HIGHLIGHTS NEW YORK 1775 Broadway. New York NY 10019 Phone: (212) 586-2640 Cable Address: Cash Box NY Telex: 666123 HOLLYWOOD 6363 Sunset Blvd. (Suite 930) Joe Cohen pledges aggressive action on industry problems at Hollywood CA 90028 Phone: (213) 464-8241 1982 NARM convention (page 9). NASHVILLE 21 Music Circle East, Nashville TN 37203 Phone: (615) 244-2898 RCA Records restructures executive staff (page 9). CHICAGO CAMILLE COMPASIO, Coin Machine. Mgr. 1442 S. 61st Ave.. Cicero IL 60650 New and developing acts highlight first quarter album releases Phone: (312) 863-7440 9). WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Segmentation of Skin Lesion Using Cohen–Daubechies–Feauveau Biorthogonal Wavelet

Khalid et al. SpringerPlus (2016) 5:1603 DOI 10.1186/s40064-016-3211-4 RESEARCH Open Access Segmentation of skin lesion using Cohen–Daubechies–Feauveau biorthogonal wavelet Shehzad Khalid1*, Uzma Jamil1,2, Kashif Saleem1, M. Usman Akram3, Waleed Manzoor1, Waqas Ahmed1 and Amina Sohail1 *Correspondence: shehzad_ [email protected] Abstract 1 Department of Computer This paper presents a novel technique for segmentation of skin lesion in dermo- Engineering, Bahria University, Islamabad, scopic images based on wavelet transform along with morphological operations. The Pakistan acquired dermoscopic images may include artifacts inform of gel, dense hairs and Full list of author information water bubble which make accurate segmentation more challenging. We have also is available at the end of the article embodied an efficient approach for artifacts removal and hair inpainting, to enhance the overall segmentation results. In proposed research, color space is also analyzed and selection of blue channel for lesion segmentation have confirmed better performance than techniques which utilizes gray scale conversion. We tackle the problem by find- ing the most suitable mother wavelet for skin lesion segmentation. The performance achieved with ‘bior6.8’ Cohen–Daubechies–Feauveau biorthogonal wavelet is found to be superior as compared to other wavelet family. The proposed methodology achieves 93.87 % accuracy on dermoscopic images of PH2 dataset acquired at Dermatology Service of Hospital Pedro Hispano, Matosinhos, Portugal. Keywords: Image enhancement, Dermoscopy, Skin cancer, Border detection, Image segmentation Background Skin cancer is one of a major concern of world due to its alarming increasing rate (Day and Barbour 2000). The most common type of skin cancer is known as melanoma which originate in the pigment-producing melanocytes in bottom layer of skin.