Ditch Companies' Reply Brief- 66 Certificate of Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 18 Southwest Idaho

Chapter: 18 State(s): Idaho Recovery Unit Name: Southwest Idaho Region 1 U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed necessary to recover and/or protect the species. Recovery plans are prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and, in this case, with the assistance of recovery unit teams, State and Tribal agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or indicate the approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Director or Regional Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature Citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Chapter 18, Southwest Idaho Recovery Unit, Idaho. 110 p. In: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus) Draft Recovery Plan. Portland, Oregon. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This chapter was developed with the assistance of the Southwest Idaho Bull Trout Recovery Unit Team, which includes: Dale Allen, Idaho Department of Fish and Game Dave Burns, U.S. Forest Service Tim Burton, U.S. Bureau of Land Management (formerly U.S. Forest Service) Chip Corsi, Idaho Department of Fish and Game Bob Danehy, Boise Corporation Jeff Dillon, Idaho Department of Fish and Game Guy Dodson, Shoshone-Paiute Tribes Jim Esch, U.S. -

History of Boise River Reservoir Operations, 1912‐1995

History of Boise River Reservoir Operations, 1912‐1995 By Jennifer Stevens, Ph.D. June 25, 2015 JENNIFER STEVENS. PH.D. 1 Table of Contents Author Background and Methodology ......................................................................................................... 4 National Archives, Seattle ......................................................................................................................... 5 National Archives, Denver ........................................................................................................................ 6 Federal Record Center, Denver ................................................................................................................. 6 Idaho State Archives, Boise ....................................................................................................................... 6 Boise State University Special Collections, Boise ...................................................................................... 6 Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Boise River: 1902‐1953 ........................................................................................................................ 10 Authorization and Construction of Arrowrock Dam ............................................................................... 10 Drought, Floods, and the Authorization of Anderson Ranch Dam ........................................................ -

Ada County Flood History

ADA HISTORY Flood - May-June 1998 Event Summary: Two weeks of rain fell on a melting melting snowpack, causing flooding along the Snake, Weiser, Payette and Boise River drainages for the second year in a row. A levee break near Eagle Island caused flooding of nearby homes. County Summary: Increased flows in the Boise River due to snowmelt and reservoir discharge caused flooding along the Greenbelt. Two sections of the Greenbelt were closed, from Leadville to the old theatre, and between River Run and Powerline Corridor. Homes in subdivisions along the river flooded, such as at River Run and Wood Duck Island. Barber Park was closed and softball games at Willow Lane Athletic Complex were cancelled. Two large trees that fell into the Boise River caused a breach in the levee at the head of Eagle Island. 60 residents were evacuated, and the Riviera Mobile Home Park and nearby homes and farmlands were flooded with a foot of water. The Idaho Statesman, May 15, 17, 28, June 2, 4, 1998 Flood - September 11, 1997 Event Summary: $57,000.00 - Flash flooding from thunderstorms caused damage in the Boise Foothills and around Pocatello County Summary: $57,000.00 - Cloudburst dropped .40" of rain in nine minutes on the Foothills area burned by the 1996 Eighth Street Fire, flooding homes, Highlands Elementary School, and streets in the Crane Creek and Hulls Gulch areas. Floodwaters were contained in several holding ponds. 15 people were evacuated and sheltered at Les Bois Junior High. The Idaho Statesman September 12 and 13, 1997, January 25, 1998 Flood - March-July, 1997 Event Summary: $50,000,000.00 - Rapid melt of a record snowmelt led to flooded rivers throughout southern Idaho. -

170 Ouintessential BOISE

170 Ouintessential BOISE InDex 14th Street, 29, 67 Boise airport, 106, 108, 139, 144, 148 c.c. Anderson house, 131 Ada County, 58, 61,139, 153 Boise Art Museum, 44, 47, 50, 58 Cabana Inn, 47 Adams, Nat, 40, 111 Boise Cascade, 55, 58, 60, 76 Caldwell, City of, 83, 90, 91 Adelmann Building, 6, 50 Boise Centre on the Grove, 23, 35, 61 Camel's Back Park, 99, 101 Albertson, Joe, 133; foundation, 112 Boise City Council, 60, 88, 128, 165, 166 Capital City Development Corporation, 58 Alscott Building, 112 113, 116 Boise City Hall, 6, 16, 56, 76; new, 68 Capital City Market, 25, 79 Alexander's men's store, 58 Boise City National Bank, 56, 76 Capitol Boulevard, 6, 31, 33, 42, 47, 68, American Linen Building, 76, 79 Boise City Parks, 55, 83, 85, 86, 165 106,143 Anduiza Building, 72 Boise Depot, 6, 31, 33, 35, 48, 141, 143, 144, Carnegie Library, 62, 99 167, 172 Carnegie, Andrew. 99 Boise Jaycees, 128 Carrere, Hastings, Shreve & Lamb, 143 Art Deco Municipal Pool at Boise Plaza, 76, 79 Cash Bazaar, 58 Boise River, 26, 31, 34, 41, 42, 43, 48, 73, Cassia, 141, 144 South Junior High School, from 107,108,110,112116; irrigation, 139, Castle Rock, 128, 133 158, 165; Chinese gardens, 150 the Boise Architectural Project. Central Fire Station, 70 Boise River Festival, 42 Chef Lou, 95 Next: The federal Works Boise Stampede, 153 Chinese, 38, 56, 150 Progress Administration Boise State University, 31, 107, 108, 111, 113, 134 Chinden Boulevard, 38, 142, 150 helped build North Junior High Boise Towne Square, 47,139,142 churches: Capitol City Christian, 97, 99; School, completed in 1936. -

History of the Boise National Fo 1905 1976. C

HISTORY OF THE BOISE NATIONAL FO 1905 1976. C 0 0 0 • A HISTORY OF THE BOISE NATIONAL FOREST 1905-1976 by ELIZABETH M. SMITH IDAHO STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOISE 1983 History of the Boise National Forest, 1905-1976, is published under a co- operative agreement between the Idaho State Historical Society and the Boise National Forest. DEDICATION This history is dedicated to the memory of Guy B. Mains, who served as supervisor of the former Payette National Forest from 1908 to 1920 and 1924 to 1925 and was supervisor of the former Boise National Forest from 1925 to 1940. He spent a total of twenty-eight years in the development of the present Boise National Forest, serving as a supervisor for over one-third of the total history of the forest from its beginning in 1905 to the present. kJ TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Boise National Forest Data ix PART I: BEFORE THE NATIONAL FOREST Indians 3 Fur Trade, Exploration, and Emigration 7 Mining 11 Chinese 18 Settlement 20 Place Names 25 7. Early Transportation 29 PART II: CREATION, DEVELOPMENT, AND ADMINISTRATION Creation of the Boise National Forest 39 Administering the Forest 44 Civilian Conservation Corps 55 Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station 61 The Lucky Peak Nursery 66 Youth Conservation Corps 68 PART III: RESOURCES AND FUNCTIONS Geology 71 Watershed, Soils, and Minerals 73 Timber Management 82 Range Management 91 Wildlife Management 99 Recreation and Land Use 105 Fire Management 111 Improvements and Engineering 127 Conclusion 135 APPENDICES Supervisors and Headquarters Locations 139 Early Mining Methods and Terms 140 Towns and Mining Camps 143 Changes in Management Through Legislation 148 Dams and Reservoirs 153 Graves in the Boise National Forest 158 BIBLIOGRAPHY 161 Illustrations Map of the Boise National Forest Photographs following page 78 . -

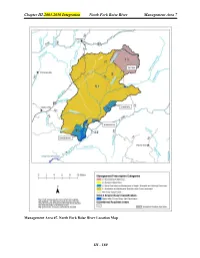

North Fork Boise River Location Map

Chapter III-2003-2010 Integration North Fork Boise River Management Area 7 Management Area 07. North Fork Boise River Location Map III - 180 Chapter III-2003-2010 Integration North Fork Boise River Management Area 7 Management Area 7 North Fork Boise River MANAGEMENT AREA DESCRIPTION Management Prescriptions - Management Area 7 has the following management prescriptions (see map on preceding page for distribution of prescriptions). Percent of Management Prescription Category (MPC) Mgt. Area 1.2 – Recommended Wilderness 13 2.2 – Research Natural Areas 1 3.2 – Active Restoration and Maintenance of Aquatic, Terrestrial, & Watershed Resources 6 5.1 – Restoration and Maintenance Emphasis within Forested Landscapes 80 General Location and Description - Management Area 7 is located within the North Fork Boise River drainage, about 5-25 miles east of Idaho City, Idaho. This management area is administered by the Idaho City Ranger District, and lies in Elmore and Boise Counties. It extends from the confluence of the Middle Fork and North Fork Boise Rivers in the southwest to the Bear River drainage in the northeast (see map, opposite page). The management area is an estimated 171,400 acres, of which the Forest Service manages over 99 percent, and less than 1 percent is privately owned. The area is surrounded by land administered by the Boise National Forest. The primary uses or activities in this management area have been timber management, developed and dispersed recreation, livestock grazing, and mineral development. Access - The main access to the area is by Forest Road 327 that leaves State Highway 21 near Idaho City, climbs over Rabbit Creek Summit, and then follows Rabbit Creek and the North Fork Boise River through the middle of the management area. -

Things You Should Know

-t ,An g6ngd g16s6t (t9'ftn:xfl?:'" Things You Fora3t S.rlca lnlormentain Region Should Know Boiso National Forsst q;,,fri3 w BOISE NANONAL FOREST LEADERSHIP TEAM Suprrrlror'o Otllcc: Forest SupeMsor - Stoyo Mcdey Deputy Forest SupeMsor - Roberta Motaen Public Allairs Oflicer - Frank Caroll Engineering/Lands . Ricfr Christensen Fire. Aviation, Planning - Jack Gollaher Administrative Officer - Al McCombie Law Enlorcem€nt - Russ Newcomb Resource Management - Wayne Patton Vegslation Management - Truman Pucibauer DLtrlct Rlngorr, Arca Bangcr: D-i Mt. Home BarBer Districl - Larry Tripp D-2 Boise Ranger District - Don Peterson D-3 ldaho City Rangff District - Kathy Lucich D-4 Cascade Renger Distract - Ronn Julian D-5 Lowman Ranger Dislrict: ilorris lftrllrnan D-6 Emmett Ranger District - Jim tancaster I I I l TABLE OF CONTENTS Subiect Paoe Forest olfice addresses and ielephone numbers I History 2 Fange 2 Recreation 4 Wildlife and Fisheries 5 TimbEr 7 Soil and Water I Engineering 8 Minerals 9 Cultural Resources 11 Fire 't2 Lands 13 Budgel and Finance t5 Personnel t8 Civil Rights Program 19 Forest Health and Salety Committee 20 Glossary ol Abbreviations 21 BOISE NATIONAL FOREST OFFICE ADDRESSES Forest Supervisor Mt. Home Ranger District (D-1) 1750 Front St. 2'180 American Legion Blvd. Boise, lD 83702 Mt. Home, lD 83647 (208) 364-4100 (208) 364-4310 Boise Ranger District (O-2) ldaho City Ranger Districl (D-3) 5493 Warm Springs Ave. P.O. Box 129 Boise, lD 837'12 ldaho City, lD 83631 (208) 364-4241 (208) 364-4330 Cascade Ranger Districl (D-4) Lowman Ranger District (D-5) P.O. -

A Study on Climate-Driven Flash Flood Risks in the Boise River Watershed, Idaho

water Article A Study on Climate-Driven Flash Flood Risks in the Boise River Watershed, Idaho Jae Hyeon Ryu 1,* and Jungjin Kim 2 1 Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho, 322E. Front ST, Boise, ID 83702, USA 2 Texas A&M AgriLife Research (Texas A&M University System), P.O. Box 1658, Vernon, TX 76384, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 March 2019; Accepted: 14 May 2019; Published: 18 May 2019 Abstract: We conducted a study on climate-driven flash flood risk in the Boise River Watershed using flood frequency analysis and climate-driven hydrological simulations over the next few decades. Three different distribution families, including the Gumbel Extreme Value Type I (GEV), the 3-parameter log-normal (LN3) and log-Pearson type III (LP3) are used to explore the likelihood of potential flash flood based on the 3-day running total streamflow sequences (3D flows). Climate-driven ensemble streamflows are also generated to evaluate how future climate variability affects local hydrology associated with potential flash flood risks. The result indicates that future climate change and variability may contribute to potential flash floods in the study area, but incorporating embedded-uncertainties inherited from climate models into water resource planning would be still challenging because grand investments are necessary to mitigate such risks within institutional and community consensus. Nonetheless, this study will provide useful insights for water managers to plan out sustainable water resources management under an uncertain and changing climate. Keywords: flood frequency analysis; flash flood; climate change and variability; Boise River Watershed; HSPF 1. -

South W Es T

Southwest 16 Idaho Fishing Seasons & Rules 2016-2018 idfg.idaho.gov Southwest Idaho Fishing Seasons & Rules 2016-2018 idfg.idaho.gov 17 SOUTHWEST REGION General Fishing Season for the Southwest Region All Waters Open All Year Except as modified in Southwest Region Special Rule Waters on Pages 19-20. Fishing is not allowed within the posted upstream and downstream boundary of any fish weir or trap. Daily Bag Limits for the Southwest Region The following daily bag limits apply to all waters of the Southwest Region except as modified in Southwest Region Special Rule Waters on Pages 19-20. The possession limit is 3-times the daily bag limit after the second day of the season. Bass (largemouth and smallmouth) • Fishing for or targeting steelhead is prohibited unless a • Bass limit is 6, both species combined steelhead season is specifically opened for that water (see pages 39-43) • None under 12 inches Sturgeon Brook Trout • Sturgeon limit is 0, catch-and-release • Brook trout limit is 25 • Sturgeon must not be removed from the water and must be • Harvest allowed during any open season unless otherwise released upon landing noted under Special Rules – if gear or bait restrictions are listed, they must be followed when fishing for brook trout • Barbless hooks and sliding sinkers are required, see Page Bull Trout 52 for details Southwest • Bull trout limit is 0, catch-and-release Tiger Muskie • Tiger Muskie limit is 2, none under 40 inches • No bull trout harvest is allowed Kokanee Trout includes brown trout, lake trout, golden trout, Arctic -

Part 2. RISK ASSESSMENT

Part 2. RISK ASSESSMENT 7. DAM/CANAL FAILURE 7.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND 7.1.1 Causes of Dam Failure Dam failures in the United States typically occur in one of four ways: • Overtopping of the primary dam structure, which accounts for 34 percent of all dam failures, can occur due to inadequate spillway design, settlement of the dam crest, blockage of spillways, and other factors. • Foundation defects due to differential settlement, slides, slope instability, uplift pressures, and foundation seepage can also cause dam failure. These account for 30 percent of all dam failures. • Failure due to piping and seepage accounts for 20 percent of all failures. These are caused by internal erosion due to piping and seepage, erosion along hydraulic structures such as spillways, erosion due to animal burrows, and cracks in the dam structure. • Failure due to problems with conduits and valves, typically caused by the piping of embankment material into conduits through joints or cracks, constitutes 10 percent of all failures. The remaining 6 percent of dam failures are due to miscellaneous causes. Many are secondary results of other disasters, such as earthquakes, landslides, storms, snowmelt, equipment malfunction, structural damage, and sabotage. The most likely disaster-related causes of dam failure in Ada County are earthquakes, excessive rainfall and landslides. Poor construction, lack of maintenance and repair, and deficient operational procedures are preventable or correctable through regular inspections. Terrorism and vandalism are concerns that all operators of public facilities plan for; these threats are under continuous review by public safety agencies. 7.1.2 Irrigation Canals Much of the arid land of Southwest Idaho was developed through reclamation projects of the early 1900s. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2020 to 09/30/2020 Sawtooth National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2020 to 09/30/2020 Sawtooth National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Nancy Rusho 228, subpart A. Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-731-9196 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] *UPDATED* Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 11/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) 07/01/2020 04:05 am MT Page 1 of 9 Sawtooth National Forest Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Amendments to Land - Land management planning In Progress: Expected:07/2020 07/2020 John Shivik Management Plans Regarding - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Objection Period Legal Notice 801-625-5667 Sage-grouse Conservation 08/02/2019 [email protected] EIS Description: The Forest Service is considering amending its land management plans to address new and evolving issues arising since implementing sage-grouse plans in 2015. -

Refugees Transform the City of Trees Todd Shallat (Editor) Boise State University, [email protected]

Boise State University ScholarWorks Faculty Authored Books 2017 Half the World: Refugees Transform the City of Trees Todd Shallat (editor) Boise State University, [email protected] Kathleen Rubinow Hodges (editor) Idaho State Historial Society Errol D. Jones (editor) Boise State University, [email protected] Laura Winslow (editor) Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/fac_books Part of the Public History Commons, and the Urban Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shallat, Todd (editor); Rubinow Hodges, Kathleen (editor); Jones, Errol D. (editor); and Winslow, Laura (editor), "Half the World: Refugees Transform the City of Trees" (2017). Faculty Authored Books. 481. http://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/fac_books/481 Half the World: Refugees Transform the City of Trees is volume 8 of the Investigate Boise Community Research Series Half the World Half Brief synopsis goes here. Refugees Transform the City of Trees of City the Refugees Transform Half the World “Quote goes here.” – COREY COOK, DEAN, BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF PUBLIC SERVICE Refugees Transform the City of Trees Investigate Boise Community Research Series Half the World Refugees Transform the City of Trees INVESTIGATE BOISE COMMUNITY RESEARCH SERIES BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY VOL. 8 2017 The Investigate Boise Community Research Series publishes fact-based essays of popular scholarship concerning the problems and values that shape metropolitan growth. VOL. 1: Making Livable Places: Transportation, Preservation, and the Limits of Growth (2010) VOL. 2: Growing Closer: Density and Sprawl in the Boise Valley (2011) VOL. 3: Down and Out in Ada County: Coping with the Great Recession, 2008-2012 (2012) VOL. 4: Local, Simple, Fresh: Sustainable Food in the Boise Valley (2013) VOL.