PNAAF616.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slope Disasters in Mauritius 4-5 115

Appendix 3.2.4 Effects of the constructed countermeasure works (evaluations) JICA Technical cooperation project: Landslide adviser for Mauritius (Final Report) Appendix 3.2.4 Effects of the constructed countermeasure works (evaluations) Existing slope countermeasures were found only in two sites of the total 18, and it was judged that those countermeasures were insufficient by MPI and JET. <Management No.2016-010, Maconde> This slope is located at the cape of Maconde on the south coast of the island. Most of the rock falls were from the basalt part of the cliff. In July and August 2014, RDA carried out removal works of rocks which were unstable and close to the road, and a new road (shift of alignment) was built to reduce the damage from rock falls. In addition, a retaining wall with a rockfall protection fence has been installed in one part of the site. However, it was judged that those countermeasures were insufficient. Rock falls and small rock failures are also a frequent occurrence along the new road because the rocks are weathered, and there is a high possibility of rock fall in future. Photo 1 Maconde (Management No.2016-010), 5 August 2016 (Source: JET) 1 JICA Technical cooperation project: Landslide adviser for Mauritius (Final Report) Appendix 3.2.4 <Management No. 2016-018, Hermitage> This site is situated in the vicinity of Grand River North West. As an existing countermeasure, a boundary wall was constructed by the land developer, but it had been already collapsed in 2012. In the future, a retaining wall should be installed there as a permanent countermeasure for the slope. -

2011 Housing and Population Census

REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS Ministry of Finance and Economic Development STATISTICS MAURITIUS ________ 2011 HOUSING AND POPULATION CENSUS REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS ANALYSIS REPORT Volume IV – Migration August 2014 Contents 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………… 1 2. Highlights……………………………………………………………………………... 1 3. Internal Migration……………………………………………………………………... 3 4. Commuting to work…………………………………………………………………… 7 5. International migration………………………………………………………………... 10 6. Notes………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 6.1 Contact person …………………………………………………………………… 14 6.2 List of Tables…………………………………………………………………....... 14 6.3 List of Figures……………………………………………………………………. 14 6.4 Annexes…………………………………………………………………………... 15 2011 Population Census Migration Report 1. Introduction Migration is the movement of people from one place to another in search of better opportunities. It involves a change in the place of usual residence either to another region within the same country (internal migration), or to another country (international migration). Another important part of people’s movement is related to activities of daily life, mainly commuting to and from work, and can also be of interest to users. This report gives an overview of migration, both internal and international, in the Republic of Mauritius and includes a section on commuting to work based on data collected at the 2011 Population Cenus. Figure 1. Reproduction of the Question on Usual Address five Most of the migration statistics are based on years ago from 2011 Population Census data collected through the question on place of usual residence 5 years ago (Figure 1) and on place of current usual residence. It is to be noted that 0.6% of the census population did not state their usual address in 2006. These people have been excluded from this analysis, and therefore the migration numbers may undercount, though to a little extent, the actual number of migrants between 2006 and 2011. -

A.2. the Population of Mauritius: Facts and Trends

MMigrationigration in Mauritius A COUNTRY PROFILE 2013 M igration in Mauritius igration A COUNTRY PROFILE 2013 PROFILE A COUNTRY 17 route des Morillons, P.O. Box 17, 1211 Geneva 19, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 717 9111 • Fax: +41 22 798 6150 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: http://www.iom.int The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in the meeting of operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This publication was made possible through the financial support provided by the IOM Development Fund (IDF). Publisher: International Organization for Migration (IOM) 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel: +41 22 717 91 11 Fax: +41 22 798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int _____________________________________________________ © 2014 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

ASSESSING the CLIMATE CHANGE-MIGRATION NEXUS THROUGH the LENS of MIGRANTS: the Case of the Republic of Mauritius

This project is funded This project is implemented by the by the European Union International Organization for Migration ANOTHER MANAM? The forced migration of the population of Manam Island, Papua New Guinea, due to volcanic eruptions 2004–2005 eruptions volcanic due to Guinea, New of Manam Island, Papua of the population migration MANAM? The forced ANOTHER ASSESSING THE CLIMATE CHANGE-MIGRATION NEXUS THROUGH THE LENS OF MIGRANTS: 17 route des Morillons, P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19, Switzerland The Case of the Republic of Mauritius Tel.: +41 22 717 9111 • Fax: +41 22 798 6150 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.iom.int This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union and of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Development Fund. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union or IOM. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. -

Port Louis 2030 Investing in the City’S Cultural Assets

Port Louis 2030 Investing in the city’s cultural assets Enrico Eraldo Bertacchini and Alessio Re [ CULTURE AT WORK ] I rapporti di ricerca DEL CENTRO STUDI SILVIA SANTAGATA-EBLA [Culture at work] I rapporti di ricerca del CSS-EBLA The research reports of CSS-EBLA [Culture at work] The research reports of CSS-EBLA PORT LOUIS 2030 INVESTING IN THE CITY’S CULTURAL ASSETS THE LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR PORT LOUIS - MAURITIUS PORT LOUIS 2030 Culture at work I rapporti di ricerca del CSS-EBLA The research reports of CSS-EBLA PORT LOUIS 2030 [Culture at work] I rapporti di ricerca del CSS-EBLA The research reports of CSS-EBLA Collana [CULTURE AT WORK] The research reports of CSS_EBLA PORT LOUIS 2030 Culture at work I rapporti di ricerca del CSS-EBLA The research reports of CSS-EBLA The Scientific Committee of the Research Centre Silvia Santagata is made up by: Francesco Bandarin, UNESCO and IUAV University, Venice, Italy Christian Barrère, Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne, Reims, France Pierre-Jean Benghozi, Ecole Polytechnique Universitè Paris Saclay, France Lluis Bonet, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain Tiziana Cuccia, University of Catania, Catania, Italy Xavier Greffe, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France Guido Guerzoni, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy Massimo Marrelli, The University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy Angelo Miglietta, IULM University, Milan, Italy Andy C. Pratt, City University of London, Great Britain Pier Luigi Sacco, IULM University, Milan, Italy Giovanna Segre, University of Turin, Italy David -

Some Policy Suggestions Based on a Survey of Schools: Mauritius

SACMEQ Policy Research: Report No. 1 Series Editor: Kenneth N. Ross The quality of education: some policy suggestions based on a survey of schools Mauritius bY Dhurumbeer Kulpoo Ministry of Education and Human Resource Development Port Louis, Mauritius International Institute for Ministry of Education and Educational Planning, Human Resource Development, UNESCO Mauritius The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO or IIEP concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. This document has been composed by IIEP Publications and printed in IIEP’s Printshop Published by the International Institute for Educational Planning 7-9 rue Eugene-Delacroix, 75116 Paris, France Cover design by Marie Moncet. Woodcut by Helene D&y. 0 UNESCO 1998 Foreword The Southern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) is a consortium of Ministries of Education located in the Southern Africa sub-region. For several years these Ministries have worked in close partnership with the IIEP in order to undertake educational policy research with the main aim of generating reliable information that can be used by decision-makers to plan the quality of education. In January 1997 the Government of Zimbabwe officially registered SACMEQ as an international non-governmental organization. SACMEQ’s Sub-regional Co-ordinating Centre is located within UNESCO’s Harare Office. The work of the Centre is managed by a Director and is guided by a Committee chaired by Zimbabwe’s Minister of Education. -

Download Menu

ACTIVITIES GUIDE ABOUT MAURITIUS auritius, known officially as the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation located off the coast of the African con- tinent in the southwest Indian Ocean. It is a volcanic M island of lagoons and palm-fringed beaches with coral reefs surrounding most of the coastline. Mauritius is situated approximately 2400 kilometers off the South East Coast of Africa. The island covers an area of 1,865 square kilometers or 720 square miles, with 330 kilometers of coastline. Mauritius is 45km in width and 65km in length. Mauritius is a densely populated island of around 1.2 million people. It has a reputation for stability and racial harmony among its mixed population. Mauritius is known as a plural society where all the ethnic groups present: Hindus, Muslims, Creoles, Chinese and Europeans live in peace and where all the ancestral cultures have been preserved. These features make the island a unique place in the world, and the Mauritians known for their tolerance and kindness towards all people. Most Mauritians are bilingual being equally fluent in French and Eng- lish. English is the official language, but French and Creole are widely spoken. Oriental languages also form part of the linguistic mosaic. Mauritius has preserved its image as one of Africa's few social and eco- nomic success stories, being a sugar and clothing exporter and a center for up market tourism. SEA AND WATER ACTIVITIES BLUE BAY MARINE PARK Blue Bay ound South East of Mauritius, the Blue Bay marine park is framed on one side by a couple of hotels and the runway of our international airport Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Airport. -

Opportunities and Challenges of Migration in Building Resilience Against Climate Change in The

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES OF MIGRATION IN BUILDING RESILIENCE AGAINST CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS YEARS This project is funded This project is implemented by the European Union by the International Organization for Migration This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Government of the Republic of Mauritius, the European Union or the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. ______________________________ Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Evidence for Policy (MECLEP) is a three-year project funded by the European Union, implemented by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) through a consortium with six research partners. The project aims to contribute to the global knowledge base on the relationship between migration and environmental change, including climate change. The innovative research aims to formulate policy options on how migration can benefit adaptation strategies to environmental and climate change. -

Mauritius National Report Phase 1: Integrated Problem Analysis

Global Environment Facility GEF MSP Sub-Saharan Africa Project (GF/6010-0016): “Development and Protection of the Coastal and Marine Environment in Sub-Saharan Africa” MAURITIUS NATIONAL REPORT PHASE 1: INTEGRATED PROBLEM ANALYSIS Dr R. Dulymamode (National Coordinator), Dr M. Bhikajee and Mrs V. Sanassee March 2002 Disclaimer: The content of this document represents the position of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views or official policies of the Government of Mauritius, ACOPS, IOC/UNESCO or UNEP. The components of the GEF MSP Sub-Saharan Africa Project (GF/6010-0016) "Development and Protection of the Coastal and Marine Environment in Sub-Saharan Africa" have been supported, in cash and kind, by GEF, UNEP, IOC-UNESCO, the GPA Coordination Office and ACOPS. Support has also been received from the Governments of Canada, The Netherlands, Norway, United Kingdom and the USA, as well as the Governments of Côte d'Ivoire, the Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa and Tanzania. Table of Contents Page Table of Contents .....................................................................................................................................3 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 1.1 Geographic Location.................................................................................................................1 1.2 Climate......................................................................................................................................1 -

Digest of Demographic Statistics 2017

DIGEST OF DEMOGRAPHIC STATISTICS 2017 CONTACT PERSONS : Mrs C.Martial (Statistician) Mrs N. Fatha Mahomed (Senior Statistical Officer) Demography Unit Statistics Mauritius LIC Building John Kennedy Street Port Louis Tel : 2122316 2122317 2080859 Fax : 2114150 Email : [email protected] DIGEST OF DEMOGRAPHIC STATISTICS - 2017 F O R E W O R D This is the thirty-third issue of a regular publication of Statistics Mauritius on Demographic Statistics. It presents the latest available statistics on population, live births, still births, marriages, deaths and divorces. A set of population projections and life-tables is also included. As in previous issues, data are presented for the islands of Mauritius and Rodrigues, as well as for the Republic. It is hoped that the data published in this report will prove valuable to the public at large and particularly to planners and decision makers. Data required for the preparation of this report were obtained mainly from the Civil Status Division of the Prime Minister’s Office and from the Judicial Department. The assistance and cooperation of these two departments are herewith gratefully acknowledged. L. F. Cheung Kai Suet Director of Statistics Statistics Mauritius, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Port Louis. MAURITIUS October 2018 C O N T E N T S Page Introductory notes 13-18 SECTION 1 - POPULATION Table 1.1 - Estimated resident population of Mauritius as at 31st December 2016 & 2017 21 1.2 - Evolution of the resident population of the Republic of Mauritius as from the 2011 census -

Beach Authority List of Proclaimed Beaches District Wise

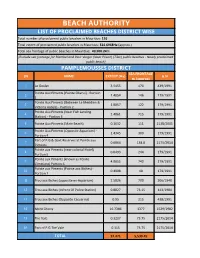

BEACH AUTHORITY LIST OF PROCLAIMED BEACHES DISTRICT WISE Total number of proclaimed public beaches in Mauritius: 126 Total extent of proclaimed public beaches in Mauritius: 324.6968Ha (approx.) Total sea frontage of public beaches in Mauritius: 49,900.24m (Exclude sea frontage for Riambel and Petit Verger (Near Prison) (Tilac) public beaches - Newly proclaimed public beach) PAMPLEMOUSSES DISTRICT SEA FRONTAGE SN NAME EXTENT (Ha) G.N m (approx) 1 Le Goulet 3.5455 470 439/1991 Pointe Aux Piments (Pointe Oberoi) - Portion 2 1.4054 146 179/1991 1 Pointe Aux Piments (Between Le Meridien & 3 1.0857 122 179/1991 Victoria Hotels) - Portion 2 Pointe Aux Piments (Near Fish Landing 4 2.4861 715 179/1991 Station) - Portion 3 5 Pointe Aux Piments (Main Beach) 0.1632 111 2138/2001 Pointe Aux Piments (Opposite Aquarium) - 6 1.4345 300 179/1991 Portion 4 Part of P.G & Govt Reserves at Pointe aux 7 0.6064 138.8 2175/2014 Piments Pointe aux Piments (near colonial Hotel) 8 0.6493 244 179/1991 Portion 5 Pointe aux Piments (known as Pointe 9 4.0055 740 179/1991 Cimetiere) Portion 6 Pointe aux Piments (Pointe aux Biches) - 10 0.4998 40 179/1991 Portion 7 11 Trou aux Biches (opposite ex-Aquarium) 2.5826 700 206/1940 12 Trou aux Biches (Infront Of Police Station) 0.8827 73.15 143/1984 13 Trou aux Biches (Opposite Casuarina) 0.95 215 438/1991 14 Mont Choisy 16.7386 1377 1529/1982 15 The Vale 0.3207 73.75 2175/2014 16 Part of P.G The Vale 0.115 73.75 2175/2014 TOTAL 37.471 5,539.45 RIVIERE DU REMPART DISTRICT SEA FRONTAGE SN NAME EXTENT (Ha) G.N m (approx) 1 Grand -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR8814 Implementation Status & Results Mauritius Infrastructure Project (P091828) Operation Name: Infrastructure Project (P091828) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 8 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 09-Dec-2012 Country: Mauritius Approval FY: 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Sector Investment and Maintenance Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 24-Sep-2009 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2014 Planned Mid Term Review Date 30-Nov-2012 Last Archived ISR Date 01-Jul-2012 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 19-Feb-2010 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 25-Feb-2013 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To prepare and begin implementation of the Public Sector Investment Program Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Road Investments 36.10 Technical Assistance in the Infrastructure Sector 14.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Public Disclosure Authorized Implementation Status Overview The implementation of the Infrastructure Project is continuing to progress well. The works are now complete on all three of the road sections that are being rehabilitated within the project,