Conch – Appendix: Discovery Interviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FFV1 Video Codec Specification

FFV1 Video Codec Specification by Michael Niedermayer [email protected] Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Terms and Definitions 2 2.1 Terms ................................................. 2 2.2 Definitions ............................................... 2 3 Conventions 3 3.1 Arithmetic operators ......................................... 3 3.2 Assignment operators ........................................ 3 3.3 Comparison operators ........................................ 3 3.4 Order of operation precedence .................................... 4 3.5 Range ................................................. 4 3.6 Bitstream functions .......................................... 4 4 General Description 5 4.1 Border ................................................. 5 4.2 Median predictor ........................................... 5 4.3 Context ................................................ 5 4.4 Quantization ............................................. 5 4.5 Colorspace ............................................... 6 4.5.1 JPEG2000-RCT ....................................... 6 4.6 Coding of the sample difference ................................... 6 4.6.1 Range coding mode ..................................... 6 4.6.2 Huffman coding mode .................................... 9 5 Bitstream 10 5.1 Configuration Record ......................................... 10 5.1.1 In AVI File Format ...................................... 11 5.1.2 In ISO/IEC 14496-12 (MP4 File Format) ......................... 11 5.1.3 In NUT File Format .................................... -

20130218 Technical White Paper.Bw.Jp

Sending, Storing & Sharing Video With latakoo © Copyright latakoo. All rights reserved. Revised 11/12/2012 Table of contents Table of contents ................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 2 2. Sending video & files with latakoo ...................................................................... 3 2.1 The latakoo app ............................................................................................ 3 2.2 Compression & upload ................................................................................. 3 2.3 latakoo minutes ............................................................................................ 4 3. The latakoo web interface .................................................................................. 4 3.1 Web interface requirements .......................................................................... 4 3.2 Logging into the dashboard .......................................................................... 4 3.3 Streaming video previews ............................................................................. 4 3.4 Downloading video ...................................................................................... 5 3.5 latakoo Pilot ................................................................................................. 5 3.6 Search and tagging ...................................................................................... -

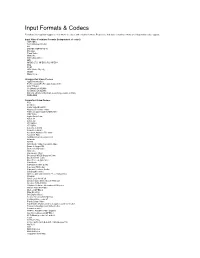

Input Formats & Codecs

Input Formats & Codecs Pivotshare offers upload support to over 99.9% of codecs and container formats. Please note that video container formats are independent codec support. Input Video Container Formats (Independent of codec) 3GP/3GP2 ASF (Windows Media) AVI DNxHD (SMPTE VC-3) DV video Flash Video Matroska MOV (Quicktime) MP4 MPEG-2 TS, MPEG-2 PS, MPEG-1 Ogg PCM VOB (Video Object) WebM Many more... Unsupported Video Codecs Apple Intermediate ProRes 4444 (ProRes 422 Supported) HDV 720p60 Go2Meeting3 (G2M3) Go2Meeting4 (G2M4) ER AAC LD (Error Resiliant, Low-Delay variant of AAC) REDCODE Supported Video Codecs 3ivx 4X Movie Alaris VideoGramPiX Alparysoft lossless codec American Laser Games MM Video AMV Video Apple QuickDraw ASUS V1 ASUS V2 ATI VCR-2 ATI VCR1 Auravision AURA Auravision Aura 2 Autodesk Animator Flic video Autodesk RLE Avid Meridien Uncompressed AVImszh AVIzlib AVS (Audio Video Standard) video Beam Software VB Bethesda VID video Bink video Blackmagic 10-bit Broadway MPEG Capture Codec Brooktree 411 codec Brute Force & Ignorance CamStudio Camtasia Screen Codec Canopus HQ Codec Canopus Lossless Codec CD Graphics video Chinese AVS video (AVS1-P2, JiZhun profile) Cinepak Cirrus Logic AccuPak Creative Labs Video Blaster Webcam Creative YUV (CYUV) Delphine Software International CIN video Deluxe Paint Animation DivX ;-) (MPEG-4) DNxHD (VC3) DV (Digital Video) Feeble Files/ScummVM DXA FFmpeg video codec #1 Flash Screen Video Flash Video (FLV) / Sorenson Spark / Sorenson H.263 Forward Uncompressed Video Codec fox motion video FRAPS: -

Scape D10.1 Keeps V1.0

Identification and selection of large‐scale migration tools and services Authors Rui Castro, Luís Faria (KEEP Solutions), Christoph Becker, Markus Hamm (Vienna University of Technology) June 2011 This work was partially supported by the SCAPE Project. The SCAPE project is co-funded by the European Union under FP7 ICT-2009.4.1 (Grant Agreement number 270137). This work is licensed under a CC-BY-SA International License Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Scope of this document 1 2 Related work 2 2.1 Preservation action tools 3 2.1.1 PLANETS 3 2.1.2 RODA 5 2.1.3 CRiB 6 2.2 Software quality models 6 2.2.1 ISO standard 25010 7 2.2.2 Decision criteria in digital preservation 7 3 Criteria for evaluating action tools 9 3.1 Functional suitability 10 3.2 Performance efficiency 11 3.3 Compatibility 11 3.4 Usability 11 3.5 Reliability 12 3.6 Security 12 3.7 Maintainability 13 3.8 Portability 13 4 Methodology 14 4.1 Analysis of requirements 14 4.2 Definition of the evaluation framework 14 4.3 Identification, evaluation and selection of action tools 14 5 Analysis of requirements 15 5.1 Requirements for the SCAPE platform 16 5.2 Requirements of the testbed scenarios 16 5.2.1 Scenario 1: Normalize document formats contained in the web archive 16 5.2.2 Scenario 2: Deep characterisation of huge media files 17 v 5.2.3 Scenario 3: Migrate digitised TIFFs to JPEG2000 17 5.2.4 Scenario 4: Migrate archive to new archiving system? 17 5.2.5 Scenario 5: RAW to NEXUS migration 18 6 Evaluation framework 18 6.1 Suitability for testbeds 19 6.2 Suitability for platform 19 6.3 Technical instalability 20 6.4 Legal constrains 20 6.5 Summary 20 7 Results 21 7.1 Identification of candidate tools 21 7.2 Evaluation and selection of tools 22 8 Conclusions 24 9 References 25 10 Appendix 28 10.1 List of identified action tools 28 vi 1 Introduction A preservation action is a concrete action, usually implemented by a software tool, that is performed on digital content in order to achieve some preservation goal. -

Arkki PLAYSTREAM Brochure

SEAMLESS Playout & Streaming Key features Arkki PLAYSTREAM • Real-time playlist seeking • Slow motion • Trim editor • Sub playlist As media companies and production outfits grow the number of • External event (Live, Command, channels and delivery methods for their subscribers, the need for CG graphics) a cost-effective solution for delivery of content becomes more • Playlist & Content Scheduling pronounced. The media workflow increases in complexity and • Drag and Drop makes investment in specialized or dedicated equipment more • Multi-select copy-paste and expensive. advanced Playlist editor • Playlist timeline Arkki PlayStream is an innovative and cost-effective platform for • Management of playlist’s gap fill with secondary playlist broadcast and media customers to digitize and playback their • File or Live input content, either as a complement or replacement of an existing • Cg playout delivery chain. Built on an open IT-based platform, Arkki • Cg editor PlayStream is powered by MediaPower proprietary technology, • Advanced Multilevel Graphic ensuring seamless integration not only with the other products of Engine plus Editor the Arkki Suite but also 3rd party systems, to provide a highly • Web Playlist Manager and full editor flexible and highly scalable end-to-end solution. Arkki PlayStream is designed to deliver and playout broadcast quality video in Proxy, Key benefits SD, HD and UHD formats, and support a variety of input / output • Deliver VoD and Live Streaming or local / central storage combinations and built-in redundancy. over the Internet • Includes powerful discovery engine Now, Media Companies can have a resilient, cost-effective video to deploy content to any device or playout, and streaming platform, provisioned with powerful user web browser applications and tools with Arkki PlayStream. -

Supported Codecs and Formats Codecs

Supported Codecs and Formats Codecs: D..... = Decoding supported .E.... = Encoding supported ..V... = Video codec ..A... = Audio codec ..S... = Subtitle codec ...I.. = Intra frame-only codec ....L. = Lossy compression .....S = Lossless compression ------- D.VI.. 012v Uncompressed 4:2:2 10-bit D.V.L. 4xm 4X Movie D.VI.S 8bps QuickTime 8BPS video .EVIL. a64_multi Multicolor charset for Commodore 64 (encoders: a64multi ) .EVIL. a64_multi5 Multicolor charset for Commodore 64, extended with 5th color (colram) (encoders: a64multi5 ) D.V..S aasc Autodesk RLE D.VIL. aic Apple Intermediate Codec DEVIL. amv AMV Video D.V.L. anm Deluxe Paint Animation D.V.L. ansi ASCII/ANSI art DEVIL. asv1 ASUS V1 DEVIL. asv2 ASUS V2 D.VIL. aura Auravision AURA D.VIL. aura2 Auravision Aura 2 D.V... avrn Avid AVI Codec DEVI.. avrp Avid 1:1 10-bit RGB Packer D.V.L. avs AVS (Audio Video Standard) video DEVI.. avui Avid Meridien Uncompressed DEVI.. ayuv Uncompressed packed MS 4:4:4:4 D.V.L. bethsoftvid Bethesda VID video D.V.L. bfi Brute Force & Ignorance D.V.L. binkvideo Bink video D.VI.. bintext Binary text DEVI.S bmp BMP (Windows and OS/2 bitmap) D.V..S bmv_video Discworld II BMV video D.VI.S brender_pix BRender PIX image D.V.L. c93 Interplay C93 D.V.L. cavs Chinese AVS (Audio Video Standard) (AVS1-P2, JiZhun profile) D.V.L. cdgraphics CD Graphics video D.VIL. cdxl Commodore CDXL video D.V.L. cinepak Cinepak DEVIL. cljr Cirrus Logic AccuPak D.VI.S cllc Canopus Lossless Codec D.V.L. -

Vicbond007's Guide to Working with DVD Footage

VicBond007’s Guide to Working with DVD Footage for Use in Anime Music Videos Copying a DVD Copying a DVD The first step to allow you to use DVD footage as your source, is to copy the DVD to your hard drive. Commercial DVDs are protected by a Content Scrambling System, abbreviated as CSS. CSS is a set of 5, 2-digit hexidecimal keys that are only supposedly readable by set-top DVD players, and DVD player software. The purpose of this scrambling code is to prevent you from directly accessing the contents of the disc on your pc, otherwise you could easily make a perfect digital copy by just dragging and drop- ping the contents of the disk to your computer, or decoding the video stream directly off the Figure 1: DVD decrypter version 3.2.3.0 detecting the presence of my laptop’s DVD drive, as well as the disc to an AVI or some other file format. fact that Wolf’s Rain: Disc 8 is in the drive. If you tried to decode the contents of a DVD directly off the disc, the picture would be unrec- ognizable and scattered with various pink and green boxes. If you try to drag the .vob files off the disc, in most situations, it will transfer, however the data will just be unreadable and appear corrupt. If you want to know all the geeky information about CSS, then you can find out all about it at the following address: http://www.alleged.com/mirrors/DVD-CSS/ The solution is to copy the DVD to our drive, and remove the encryption in the process. -

Video Encoding with Open Source Tools

Video Encoding with Open Source Tools Steffen Bauer, 26/1/2010 LUG Linux User Group Frankfurt am Main Overview Basic concepts of video compression Video formats and codecs How to do it with Open Source and Linux 1. Basic concepts of video compression Characteristics of video streams Framerate Number of still pictures per unit of time of video; up to 120 frames/s for professional equipment. PAL video specifies 25 frames/s. Interlacing / Progressive Video Interlaced: Lines of one frame are drawn alternatively in two half-frames Progressive: All lines of one frame are drawn in sequence Resolution Size of a video image (measured in pixels for digital video) 768/720×576 for PAL resolution Up to 1920×1080p for HDTV resolution Aspect Ratio Dimensions of the video screen; ratio between width and height. Pixels used in digital video can have non-square aspect ratios! Usual ratios are 4:3 (traditional TV) and 16:9 (anamorphic widescreen) Why video encoding? Example: 52 seconds of DVD PAL movie (16:9, 720x576p, 25 fps, progressive scan) Compression Video codec Raw Size factor Comment 1300 single frames, MotionTarga, Raw frames 1.1 GB - uncompressed HUFFYUV 459 MB 2.2 / 55% Lossless compression MJPEG 60 MB 20 / 95% Motion JPEG; lossy; intraframe only lavc MPEG-2 24 MB 50 / 98% Standard DVD quality X.264 MPEG-4 5.3 MB 200 / 99.5% High efficient video codec AVC Basic principles of multimedia encoding Video compression Lossy compression Lossless (irreversible; (reversible; using shortcomings statistical encoding) in human perception) Intraframe encoding -

Sakura-Con Opening Ceremonies Video Contest Attention All AMV

Sakura-Con Opening Ceremonies Video Contest Attention all AMV creators and video editors! Enjoy making videos? Why not try your hand at making a video for the 2015 Opening Ceremonies? We want the opening video to start Sakura-Con off right, and we want you to help! What’s in it for us? We play your video in front of everyone at Opening Ceremonies, and you get to show off your work in front of everyone, while also receiving two complimentary memberships for Sakura-Con 2015. It’s a win-win for everyone! Online-Submission forms will be available shortly, and the contest will close on January 19th, 2015. Please read all of the rules for complete details. Rules: 1. Sakura-Con Opening Ceremonies Video Contest is open to all entrants. All entrants under 18 years of age will need to provide parent/guardian contact information with their entry. 2. Videos should be roughly 4 minutes in length, no more than 5 minutes in length, and at least 2 minutes in length. Videos shorter than 2 minutes may be considered, but priority will be given to videos closer to the 4 minute mark. 3. Please do not include any bumpers or slates for your entries, and keep your intros and exits free of any text that does not relate to the video itself. This means no intro or exit text overlays, bugs, watermarks or similar graphics. 4. All videos are required to be in at least a resolution of 640x480. However, preference will be given to those with 720p or higher resolution. -

Video Codecs Comparison Part 2: PSNR Diagrams

Video Codecs Comparison Part 2: PSNR Diagrams Project head: Dmitriy Vatolin Testing: Sergey Grishin Translating: Daria Kalinkina, Stanislav Soldatov Preparing: Nikolai Trunichkin 9 testing sequences! 11 days (260 hours) total compression time! 33 tested codecs! 2430 resulting sequences! May 2003 CS MSU Graphics&Media Lab Video Group http://www.compression.ru/video/ VIDEO CODECS COMPARISON TEST/ PART 2 CS MSU GRAPHICS&MEDIA LAB VIDEO GROUP MOSCOW, 15 MAY 2003 Video Codecs Comparison Part 2: PSNR Diagrams For All Video Codecs 15 May 2003 Contents Contents ..............................................................................................................................2 Disclaimer............................................................................................................................4 Lossless codecs ..................................................................................................................5 Microsoft codec`s versions ..................................................................................................7 Y-PSNR / Frame Size Diagrams........................................................................................12 MPEG4 ......................................................................................................................................13 Microsoft 3688 v3, Divx 3.1, Divx 4.02, Divx 5.02 and Xvid 2.1..................................13 Microsoft v1 & v2 & v3, Divx 4.02, 3IVX D4................................................................17 JPEG .........................................................................................................................................21 -

Rdvideo: a New Lossless Video Codec on GPU

RDVideo: A New Lossless Video Codec on GPU Piercarlo Dondi1, Luca Lombardi1,andLuigiCinque2 1Department of Computer Engineering and Systems Science, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy 2Department of Computer Science, University of Roma ”La Sapienza”, Via Salaria 113, Roma, Italy {piercarlo.dondi,luca.lombardi}@unipv.it, [email protected] Abstract. In this paper we present RDVideo, a new lossless video codec based on Relative Distance Algorithm. The peculiar characteristics of our method make it particularly suitable for compressing screen video recordings. In this field its compression ratio is similar and often greater to that of the other algorithms of the same category. Additionally its high degree of parallelism allowed us to develop an efficient implementa- tion on graphic hardware, using the Nvidia CUDA architecture, able to significantly reduce the computational time. Keywords: Lossless Video Coding, Screen Recording, GPGPU. 1 Introduction Recording screen activity is an important operation that can be useful in dif- ferent fields, from remote descktop applications to usability tests. In the first case is essential to reduce the amount of trasferred data, it is not strictly nec- essary a high quality video compression: a lossy compression and a small set of informations (e.g. the list of pressed keys or of started programs) are generally sufficient[1]. On the contrary, in the second case, it is generally useful to have a complete recording of the screen in order to study the user interaction. There are many screen recording system on market [2] that implement differ- ent features, but all of them use traditional codec for compress the output. -

On Audio-Visual File Formats

On Audio-Visual File Formats Summary • digital audio and digital video • container, codec, raw data Reto Kromer • AV Preservation by reto.ch • different formats for different purposes Open-Source Tools and Resources audio-visual data transformations for Audio-Visual Archives • Elías Querejeta Zine Eskola Donostia (San Sebastián), Spain 19, 21, 26 and 28 May 2020 1 2 Digital Audio • sampling Digital Audio • quantisation 3 4 Sampling • 44.1 kHz • 48 kHz • 96 kHz • 192 kHz digitisation = sampling + quantisation • 500 kHz 5 6 Quantisation • 16 bit (216 = 65 536) • 24 bit (224 = 16 777 216) • 32 bit (232 = 4 294 967 296) Digital Video 7 8 Digital Video Resolution • resolution • SD 480i / SD 576i • bit depth • HD 720p / HD 1080i • linear, power, logarithmic • 2K / HD 1080p • colour model • 4K / UHD-1 • chroma subsampling • 8K / UHD-2 • illuminant 9 10 Bit Depth Linear, Power, Logarithmic • 8 bit (28 = 256) «medium grey» • 10 bit (210 = 1 024) • linear: 18% • 12 bit (212 = 4 096) • power: 50% • 16 bit (216 = 65 536) • logarithmic: 50% • 24 bit (224 = 16 777 216) 11 12 Colour Model • XYZ, L*a*b* • RGB / R′G′B′ / CMY / C′M′Y′ • Y′IQ / Y′UV / Y′DBDR • Y′CBCR / Y′COCG • Y′PBPR 13 14 15 16 RGB24 00000000 11111111 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 11111111 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 11111111 00000000 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 00000000 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 00000000 11111111 17 18 Compression • uncompressed • lossless compression • lossy compression • chroma subsampling • born compressed 19 20 Uncompressed Lossless