Nipah Virus Outbreak with Person-To-Person Transmission in a District of Bangladesh, 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Antibiotics for Cholera Chemoprevention

Use of antibiotics for cholera chemoprevention Iza Ciglenecki, Médecins Sans Frontières GTFCC Case management meeting, 2018 Outline of presentation • Key questions: ₋ Rationale for household prophylaxis – household contacts at higher risk? ₋ Rationale for antibiotic use? ₋ What is the effectiveness? ₋ What is the impact on the epidemic? ₋ Risk of antimicrobial resistance ₋ Feasibility during outbreak control interventions • Example: Single-dose oral ciprofloxacin prophylaxis in response to a meningococcal meningitis epidemic in the African meningitis belt: a three-arm cluster-randomized trial • Prevention of cholera infection among contacts of case: a cluster-randomized trial of Azithromycine Rationale: risk for household contacts Forest plot of studies included in meta-analysis: association of presence of household contact with cholera with symptomatic cholera Richterman et al. Individual and Household Risk Factors for Symptomatic Cholera Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JID 2018 Rationale: clustering of cholera cases in time and space Relative risk for cholera among case cohorts compared with control cohorts at different spatio-temporal scales Living within 50 m of the index case: RR 36 (95% CI: 23–56) within 3 days of the index case presenting to the hospital Debes et al. Cholera cases cluster in time and space in Matlab, Bangladesh: implications for targeted preventive interventions. Int J Epid 2016 Rationale: clustering of cholera cases in time and space Relative risk of next cholera case occuring at different distances from primary case Relative risk of next cholera case being within specific distance to another case within days 0-4 Within 40 m: Ndjamena: RR 32.4 (95% 25-41) Kalemie: RR 121 (95% CI 90-165) Azman et al. -

Evidence That Coronavirus Superspreading Is Fat-Tailed BRIEF REPORT Felix Wonga,B,C and James J

Evidence that coronavirus superspreading is fat-tailed BRIEF REPORT Felix Wonga,b,c and James J. Collinsa,b,c,d,1 aInstitute for Medical Engineering and Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139; bDepartment of Biological Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139; cInfectious Disease and Microbiome Program, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02142; and dWyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University, Boston, MA 02115 Edited by Simon A. Levin, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and approved September 28, 2020 (received for review September 1, 2020) Superspreaders, infected individuals who result in an outsized CoV and SARS-CoV-2 exhibited an exponential tail. We number of secondary cases, are believed to underlie a significant searched the scientific literature for global accounts of SSEs, in fraction of total SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Here, we combine em- which single cases resulted in numbers of secondary cases pirical observations of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 transmission and greater than R0, estimated to be ∼3 to 6 for both coronaviruses extreme value statistics to show that the distribution of secondary (1, 7). To broadly sample the right tail, we focused on SSEs cases is consistent with being fat-tailed, implying that large super- resulting in >6 secondary cases, and as data on SSEs are sparse, spreading events are extremal, yet probable, occurrences. We inte- perhaps due in part to a lack of data sharing, we pooled data for grate these results with interaction-based network models of disease SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, to avoid higher- transmission and show that superspreading, when it is fat-tailed, order transmission obfuscating the cases generated directly by leads to pronounced transmission by increasing dispersion. -

Shigellosis Outbreak Investigation & Control

SHIGELLOSIS OUTBREAK INVESTIGATION & CONTROL IN CHILD CARE CENTERS / PRE-SCHOOLS Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment Communicable Disease Epidemiology Program For information on Shigella disease control and epidemiology, including reporting requirements and routine case investigation, please refer to the CPDHE Communicable Disease Manual, available at: http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/dc/Epidemiology/dc_manual.html When a case of shigellosis occurs in a child care center attendee or worker, immediate involvement of public health authorities is critical. Shigella spreads very quickly through child care centers, but can be controlled if appropriate action is taken. When an outbreak occurs, the first case to be diagnosed may be a child, or an adult contact of a child. For a single case of shigellosis associated with a child care center: • Children with shigellosis should not be permitted to re-enter the child care center until diarrhea has resolved and either the child has been treated with an effective antibiotic for 3 days or there are 2 consecutive negative stool cultures. • It is important to obtain the antibiotic susceptibility pattern for the isolate from the physician or the clinical laboratory that performed the test in order to determine if a child has been treated with an effective antibiotic. • Parents of cases should be counseled not to take their children to another child care center during this period of exclusion. • Public health or environmental health staff should visit the facility, review hygienic procedures, and reinforce the importance of meticulous handwashing with childcare center staff. • Look for symptoms consistent with Shigella infection (diarrhea and fever) in other children or staff during the 3 weeks previous to the report of the index case. -

Patterns of Virus Exposure and Presumed Household Transmission Among Persons with Coronavirus Disease, United States, January–April 2020 Rachel M

Patterns of Virus Exposure and Presumed Household Transmission among Persons with Coronavirus Disease, United States, January–April 2020 Rachel M. Burke, Laura Calderwood, Marie E. Killerby, Candace E. Ashworth, Abby L. Berns, Skyler Brennan, Jonathan M. Bressler, Laurel Harduar Morano, Nathaniel M. Lewis, Tiff anie M. Markus, Suzanne M. Newton, Jennifer S. Read, Tamara Rissman, Joanne Taylor, Jacqueline E. Tate, Claire M. Midgley, for the COVID-19 Case Investigation Form Working Group We characterized common exposures reported by a oronavirus disease (COVID-19) was fi rst identi- convenience sample of 202 US patients with corona- Cfi ed in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 (1). The virus disease during January–April 2020 and identifi ed fi rst reported case in the United States was identifi ed factors associated with presumed household transmis- in January 2020 (2); by mid-March, cases had been re- sion. The most commonly reported settings of known ported in all 50 states (3). On March 16, 2020, the White exposure were households and healthcare facilities; House Coronavirus Task Force published guidance for among case-patients who had known contact with curbing community spread of COVID-19 (4); soon af- a confi rmed case-patient compared with those who ter, states began to enact stay-at-home orders (5). By did not, healthcare occupations were more common. late May 2020, all 50 states had begun easing restric- Among case-patients without known contact, use of tions; reported cases reached new peaks in the summer public transportation was more common. Within the household, presumed transmission was highest from and then winter months of 2020 (6,7). -

Sexually Transmitted Infections: Epidemiology and Control

40 Rev Esp Sanid Penit 2011; 13: 58-66 M Díez, A Díaz. Sexually transmitted infections: Epidemiology and control Sexually transmitted infections: Epidemiology and control M Díez, A Díaz Epidemiology Department on HIV and Risk Behaviors. Secretary of the National Plan on AIDS. Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality. National Centre for Epidemiology. Health Institute Carlos III ABSTRACT Sexually transmitted infections (STI) include a group of diseases of diverse infectious etiology in which sexual transmission is relevant. The burden of disease that STI globally represent is unknown for several reasons. Firstly, asymptomatic infections are common in many STI; secondly, diagnostic techniques are not available in some of the most affected countries; and finally, surveillance systems are inexistent or very deficient in many areas of the world. The World Health Organization has estimated that in 1999 there were 340 million new cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, Chlamydia infection and trichomoniasis. An increasing trend in the incidence of gonorrhea and syphilis has been noticed in the last years in the European Union, including Spain. Co-infection with other STI, especially HIV, should be ruled out in all STI patients. Chlamydia screening is also of partic- ular importance since this is the most common STI in Europe and frequently goes unnoticed. STI prevention and control should be based on health education, early diagnosis and treatment, screening for asympto- matic infections, contact investigation and vaccination for those diseases for -

Family-Based Index Case Testing To

Family-based index case testing to identify children with HIV Shaffiq Essajee1, Nande Putta1, Serena Brusamento2, Martina Penazzato2, Stuart Kean3 and Daniella Mark4 1United Nations Children’s Fund; 2World Health Organization; 3World Council of Churches – Ecumenical Advocacy Alliance; 4Paediatric-Adolescent Treatment Africa Rationale Pediatric HIV treatment coverage is stagnating. The most recent estimates suggest 01 that only 46% of children living with HIV are on treatment, well below the AIDS Free target of 1.6 million by the end of 2018.1 A key challenge is to identify children who are living with HIV who have been missed through routine testing services. For children in the 0-14 year age group, over 95% of HIV infections are acquired as a result of vertical transmission. As a result, historical approaches to pediatric diagnosis have tended to focus on early infant diagnosis (EID) within the context of prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) programs. Testing the family of adult or child ‘index’ cases can serve as an entry point for identification of children living with HIV not identified through PMTCT program testing. This type of family-based approach to HIV testing and service delivery enables parents and their children to access care as a unit. Such approaches may improve retention and offer a convenient service for families affected by HIV. Unlike other types of routine approaches to pediatric HIV testing – such as testing in inpatient wards, sick child clinics, malnutrition centres or immunization clinics – index case testing is a potentially high-yield identification strategy irrespective of national seroprevalence. In fact, yield may be higher in low-prevalence countries where programs may be less mature and access to HIV testing and prevention services is lower, resulting in large gaps in PMTCT and EID coverage. -

Sexually Transmitted Infections Introduction and General Considerations Date Reviewed: July, 2010 Section: 5-10 Page 1 of 13

Sexually Transmitted Infections Introduction and General Considerations Date Reviewed: July, 2010 Section: 5-10 Page 1 of 13 Background Information The incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) in Saskatchewan has been increasing over the past number of years. This may be due in part to the introduction of testing procedures that are easier to complete and less invasive. In Saskatchewan, the rates for chlamydia have been among the highest in Canada. Refer to http://dsol- smed.phac-aspc.gc.ca/dsol-smed/ndis/c_indp_e.html#c_prov for historical surveillance data collected by Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). STIs are transmitted in the context of other social and health challenges; the risk of recurrent exposure and infection are likely unless these underlying issues are dealt with. A holistic assessment of clients assists in identifying these underlying issues and a multidisciplinary team approach is often necessary and should involve other partners such as physicians, addiction services and mental health as required. The regulations of The Health Information Protection Act must be adhered to when involving other partners in the management of individuals or when referring individuals to other agencies. This section highlights some of the general and special considerations that should be kept in mind when conducting STI investigations. It also highlights key points and summarizes the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections which can be located at http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/std-mts/sti-its/guide-lignesdir-eng.php. Reporting Requirements Index cases must be reported to the Ministry of Health. See Reporting Requirements in the General Information section of this manual for additional information and guidelines. -

Impact Foundation Bangladesh Annual Report’ 2010

Impact Foundation Bangladesh ANNUAL REPORT’ 2010 About US Before 1990s the disability is- in the living standard of the rural gramme. sue as perceived today, was al- poor by preventing the causes of IFB employs about 200 full-time most nonexistent in the context disabilities through education, staff for its overall operation. 90% of Bangladesh. The late Sir John awareness, training, curative med- of IFB staff is field based in the Wilson CBE, OBE, DCL, who ical services and appropriate so- three IFB project sites. The field was the pioneer of the interna- cial and economic programmes.” offices are in Chuadanga, Me- tional disability movement, was IFB is governed by a Board of herpur and Impact “Jibon Tari” the inspiration of Impact Founda- Trustees and managed by a team are led by the respective Pro- tion Bangladesh. With the support of highly dedicated staff and gen- gramme Administrators. and guidance of this great leader erous volunteers. The IFB organi- IFB stepped forward in 1993 as IFB believes that disability is both zational structure involves a small a Charitable Trust and registered a cause and effect of poverty and head office located in Dhaka non-profit development organiza- persons with disabilities are the headed by the Director with three tion in Bangladesh with the aim, poorest of the poor in the context interdependent departments; Fi- “To achieve sustainable increase of Bangladesh. nance, Administration and Pro- Major Intervention of IFB Hospital Services Community Service • Surgery (Eye, ENT, Orthopedic, Plastic, hydro- -

Annual Report 2011-12

ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 BANGLADESH AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENTCORPORATION MONITORING DIVISION 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 Prepared by : Marina Sarmin Chief : Sheikh Mohammed Saiful Islam Deputy Chief : Md. Shahin Mia Research Officer Edited by : Marina Sarmin Chief Sheikh Mohammed Saiful Islam Deputy Chief : Md. Shahin Mia Research Officer Computer composed by : Md. Abul Kashem Assistant Administrative Officer Md. Humayan Kabir Assistant Personal Officer Published by : Monitoring Division 2 FOREWORD In fulfilment of the statutory requirement as outlined in the charter of the Bangladesh Agricultural Development Corporation, the annual report for the year 2011-12 has been prepared and hereby forwarded. This report contains financial & physical aspects of 24 development projects (12 under crop sub-sector and 12 under irrigation sub-sector) and 83 programs (9 programs under crop sub-sector, 73 programs under irrigation sector and one program under fertilizer management) executed by BADC. The annual report for the year 2011-12 is the outcome of extensive and collective efforts of different executing divisions of the Corporation in general and Monitoring Division in particular. It would be more appreciable if the annual report on the activities of BADC brought out in time. However, the officers and the staffs of the Monitoring Division, who worked hard for its compilation, deserve appreciation. Md. Zahir Uddin Ahmed ndc Chairman BADC 3 PREFACE Publication of annual report on the activities of BADC is a statutory obligation. In fulfillment of such statutory requirement, The Monitoring Division of the Corporation, in close co-operation of the executing divisions and project offices has prepared the annual report for 2011-12. -

The Index Case of SARS-Cov-2 in Scotland: a Case Report

Edinburgh Research Explorer The index case of SARS-CoV-2 in Scotland: a case report Citation for published version: Hill, DKJ, Russell, DCD, Clifford, DS, Templeton, DK, Mackintosh, DCL, Koch, DO & Sutherland, DRK 2020, 'The index case of SARS-CoV-2 in Scotland: a case report', Journal of Infection. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.022 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.022 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Infection Publisher Rights Statement: Author's peer reviewed manuscript as accepted for publication. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 The index case of SARS-CoV-2 in Scotland: a case report Dr Katherine J. Hill1 Dr Clark D. Russell1,2 Dr Sarah Clifford1 Dr Kate Templeton 3 Dr Claire L. Mackintosh1 Dr Oliver Koch1 Dr Rebecca K. Sutherland1 1NHS Lothian, Regional Infectious Diseases Unit, Edinburgh, EH4 2XU. 2University of Edinburgh Centre for Inflammation Research, The Queen's Medical Research Institute, Edinburgh EH16 4TJ 3NHS Lothian, Diagnostic Virology Reference Laboratory, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH16 4TJ Corresponding author: Dr Katherine J Hill, [email protected] 0131 537 2871 Abstract Since its identification in December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has infected 125,048 persons globally with cases identified in 118 countries across all continents (1). -

Ring Vaccination and Smallpox Control Mirjam Kretzschmar,* Susan Van Den Hof,* Jacco Wallinga,* and Jan Van Wijngaarden†

RESEARCH Ring Vaccination and Smallpox Control Mirjam Kretzschmar,* Susan van den Hof,* Jacco Wallinga,* and Jan van Wijngaarden† We present a stochastic model for the spread of small- We investigated which conditions are the best for effec- pox after a small number of index cases are introduced into tive use of ring vaccination, a strategy in which direct con- a susceptible population. The model describes a branching tacts of diagnosed cases are identified and vaccinated. We process for the spread of the infection and the effects of also investigated whether monitoring contacts contributes intervention measures. We discuss scenarios in which ring to the success of ring vaccination. We used a stochastic vaccination of direct contacts of infected persons is suffi- cient to contain an epidemic. Ring vaccination can be suc- model that distinguished between close and casual con- cessful if infectious cases are rapidly diagnosed. However, tacts to explore the variability in the number of infected because of the inherent stochastic nature of epidemic out- persons during an outbreak, and the time until the outbreak breaks, both the size and duration of contained outbreaks is over. We derived expressions for the basic reproduction are highly variable. Intervention requirements depend on number (R0) and the effective reproduction number (Rυ). the basic reproduction number (R0), for which different esti- We investigated how effectiveness of ring vaccination mates exist. When faced with the decision of whether to rely depends on the time until diagnosis of a symptomatic case, on ring vaccination, the public health community should be the time to identify and vaccinate contacts in the close con- aware that an epidemic might take time to subside even for tact and casual contact ring, and the vaccination coverage an eventually successful intervention strategy. -

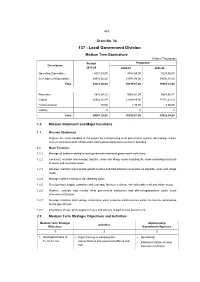

137 - Local Government Division

453 Grant No. 34 137 - Local Government Division Medium Term Expenditure (Taka in Thousands) Budget Projection Description 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 Operating Expenditure 4321,54,00 4753,69,00 5229,06,00 Development Expenditure 29919,66,00 31541,98,00 34696,18,00 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 Recurrent 7815,04,16 9003,87,04 8807,80,41 Capital 26425,35,84 27289,84,96 31115,37,59 Financial Asset 80,00 1,95,00 2,06,00 Liability 0 0 0 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 1.0 Mission Statement and Major Functions 1.1 Mission Statement Improve the living standard of the people by strengthening local government system, developing climate resilient rural and urban infrastructure and implementing socio-economic activities. 1.2 Major Functions 1.2.1 Manage all matters relating to local government and local government institutions; 1.2.2 Construct, maintain and manage Upazilla, union and village roads including the roads and bridges/culverts of towns and municipal areas; 1.2.3 Develop, maintain and manage growth centres and hats-bazaars connected via Upazilla, union and village roads; 1.2.4 Manage matters relating to safe drinking water; 1.2.5 Develop water supply, sanitation and sewerage facilities in climate risk vulnerable rural and urban areas; 1.2.6 Finance, evaluate and monitor local government institutions and offices/organizations under Local Government Division; 1.2.7 Develop, maintain and manage small-scale water resource infrastructures within the timeline determined by the government. 1.2.8 Enactment of Law, promulgation of rules and policies related to local government.