Reptiles and Amphibians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reptile and Amphibian List RUSS 2009 UPDATE

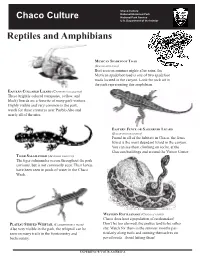

National CHistoricalhaco Culture Park National ParkNational Service Historical Park Chaco Culture U.S. DepartmentNational of Park the Interior Service U.S. Department of the Interior Reptiles and Amphibians MEXICAN SPADEFOOT TOAD (SPEA MULTIPLICATA) Best seen on summer nights after rains, the Mexican spadefoot toad is one of two spadefoot toads located in the canyon. Look for rock art in the park representing this amphibian. EASTERN COLLARED LIZARD (CROTAPHYTUS COLLARIS) These brightly colored (turquoise, yellow, and black) lizards are a favorite of many park visitors. Highly visible and very common in the park, watch for these creatures near Pueblo Alto and nearly all of the sites. EASTERN FENCE OR SAGEBRUSH LIZARD (SCELOPORUS GRACIOSUS) Found in all of the habitats in Chaco, the fence lizard is the most abundant lizard in the canyon. You can see them climbing on rocks, at the Chacoan buildings and around the Visitor Center. TIGER SALAMANDER (ABYSTOMA TIGRINUM) The tiger salamander occurs throughout the park environs, but is not commonly seen. Their larvae have been seen in pools of water in the Chaco Wash. WESTERN RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS VIRIDIS) Chaco does host a population of rattlesnakes! PLATEAU STRIPED WHIPTAIL (CNEMIDOPHORUS VALOR) Don’t be too alarmed, the snakes tend to be rather Also very visible in the park, the whiptail can be shy. Watch for them in the summer months par- seen on many trails in the frontcountry and ticularly along trails and sunning themselves on backcountry. paved roads. Avoid hitting them! EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA Amphibian and Reptile List Chaco Culture National Historical Park is home to a wide variety of amphibians and reptiles. -

Fish and Wildlife

Appendix B Upper Middle Mainstem Columbia River Subbasin Fish and Wildlife Table 2 Wildlife species occurrence by focal habitat type in the UMM Subbasin, WA. -

An Investigation of Four Rare Snakes in South-Central Kansas

• AN INVESTIGATION OF FOUR RARE SNAKES IN SOUTH-CENTRAL KANSAS •• ·: ' ·- .. ··... LARRY MILLER 15 July 1987 • . -· • AN INVESTIGATION --OF ----FOUR ----RARE SNAKES IN SOUTH-CENTRAL KANSAS BY LARRY MILLER INTRODUCTION The New Mexico blind snake (Leptotyphlops dulcis dissectus), Texas night snake (Hypsiglena torqua jani), Texas longnose snake (Rhinocheilus lecontei tessellatus), and checkered garter snake (Thamnophis marcianus marcianus) are four Kansas snakes with a rather limited range in the state. Three of the four have only been found along the southern counties. Only the Texas longnose snake has been found north of the southern most Kansas counties. This project was designed to find out more about the range, habits, and population of these four species of snakes in Kansas. It called for a search of background information on each snake, the collection of new specimens, photographs of habitat, and the taking of notes in regard to the animals. The 24 Kansas counties covered in the investigation ranged from Cowley at the southeastern most • location to Morton at the southwestern most location to Hamilton, Kearny, Finney, and Hodgeman to the north. Most of the work centered around the Red Hills area and to the east of that area. See (Fig. 1) for counties covered. Most of the work on this project was done by me (Larry Miller). However, I was often assisted in the field by a number of other persons. They will be credited at the end of this report. METHODS A total of 19 trips were made by me between the dates of 28 March 1986 and 1 July 1987 in regard to this project. -

A Taxonomic Study of the Genus Hypsiglena

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 5 Number 3 – Number 4 Article 1 12-29-1944 A taxonomic study of the genus Hypsiglena Wilmer W. Tanner Provo High School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Tanner, Wilmer W. (1944) "A taxonomic study of the genus Hypsiglena," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 5 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol5/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ., .The Great Basin Naturalist 7>^^ of Comai;^^ Published by the A«'*^ Zootomy 'U\ I^KH.MMMKNT OF ZoOI.OC.Y AND ExTOMOI.OCV UtInrT i.99»fl46*) J BiMCHAM Young UxiVEKsny. Pkovo, Utah v.,-- / B K A Hj* Volume V DECEMBER 29, 1944 Nos. 3 & 4 )\( I A TA.\( ).\JK- STL'I)\' OV TH1^ GENUS 1 IN' 'Sl( ilJ-.XA WII.MI-'.K W. TANNKRi I'r.jvo Higli ScIkxiI. Provo, Utah IXTKODUe'lION In ihc Course ol my studies of Utah specimens of the genus Hypsiglena it became apparent that 1 could better understand this genus if a large series of specimens were secured for study. Accord- ingl_\- 1 set out tcj bring together by loan as many specimens as possible. As a result over 4(XJ specimens have been assembled and studied. This C(nil(l not have been accomplished without the aid of many workers and insiiiutions who ha\e so graciously allowed me to stutly their specimens. -

Class: Amphibia Amphibians Order

CLASS: AMPHIBIA AMPHIBIANS ANNIELLIDAE (Legless Lizards & Allies) CLASS: AMPHIBIA AMPHIBIANS Anniella (Legless Lizards) ORDER: ANURA FROGS AND TOADS ___Silvery Legless Lizard .......................... DS,RI,UR – uD ORDER: ANURA FROGS AND TOADS BUFONIDAE (True Toad Family) BUFONIDAE (True Toad Family) ___Southern Alligator Lizard ............................ RI,DE – fD Bufo (True Toads) Suborder: SERPENTES SNAKES Bufo (True Toads) ___California (Western) Toad.............. AQ,DS,RI,UR – cN ___California (Western) Toad ............. AQ,DS,RI,UR – cN ANNIELLIDAE (Legless Lizards & Allies) Anniella ___Red-spotted Toad ...................................... AQ,DS - cN BOIDAE (Boas & Pythons) ___Red-spotted Toad ...................................... AQ,DS - cN (Legless Lizards) Charina (Rosy & Rubber Boas) ___Silvery Legless Lizard .......................... DS,RI,UR – uD HYLIDAE (Chorus Frog and Treefrog Family) ___Rosy Boa ............................................ DS,CH,RO – fN HYLIDAE (Chorus Frog and Treefrog Family) Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs) Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs) Suborder: SERPENTES SNAKES ___California Chorus Frog ............ AQ,DS,RI,DE,RO – cN COLUBRIDAE (Colubrid Snakes) ___California Chorus Frog ............ AQ,DS,RI,DE,RO – cN ___Pacific Chorus Frog ....................... AQ,DS,RI,DE – cN Arizona (Glossy Snakes) ___Pacific Chorus Frog ........................AQ,DS,RI,DE – cN BOIDAE (Boas & Pythons) ___Glossy Snake ........................................... DS,SA – cN Charina (Rosy & Rubber Boas) RANIDAE (True Frog Family) -

Type Locality Restriction of <I>Hypsiglena Torquata</I> Gã¼nther

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 57 Number 1 Article 11 3-7-1997 Type locality restriction of Hypsiglena torquata Günther Wilmer W. Tanner Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Tanner, Wilmer W. (1997) "Type locality restriction of Hypsiglena torquata Günther," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 57 : No. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol57/iss1/11 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 57(1), e 1997, pp. 79-82 TYPE LOCALITY RESTRICTION OF HYPSIGLENA TORQUATA GUNTHER Wilmer W Tannerl Key word.s: Hypsiglena lOrquata, Mexico, Nicaroguo.. Since the description ofHIJPsigl.ena torquata type when compared with specimens from by Giinther in 1860 and the designation of the Mazatlan, Sinaloa. He communicated his con type locality as Nicaragua, specimens have cern with Mr. J. C. Battersby at the British been collected only in central Mexico and Museum, who prOVided basic character infor north into the United States (Tanner 1946, mation for the type specimen. Dixon then con Dixon and Dean 1986). Just how far south in cluded that "the locality from which the type Mexico Hypsiglena may range is perhaps not specimen came is somewhat in doubt" and that yet known. Specimens have been taken in "until both co-types are examined and further Morelos, Guerrero, and Michoacan but not as collecting done, it would be unwise to change yet, to my knowledge, from the states of Mex the type locality, even though it appears to be ico, Puebla, Veracruz, Oaxaca, or Chiapas. -

Microhabitat and Prey Odor Selection in Hypsiglena Chlorophaea

Copeia 2009, No. 3, 475–482 Microhabitat and Prey Odor Selection in Hypsiglena chlorophaea Robert E. Weaver1 and Kenneth V. Kardong1 We studied the effects of various shelter and prey odor combinations on selection of microhabitat characters by the Desert Nightsnake, Hypsiglena chlorophaea, a dipsadine snake. We also examined the activity patterns of these snakes over a 23-h period. Three prey odors were tested, based on field work documenting natural prey in its diet: lizard, snake, mouse (plus water as control). In the first experiment, each odor was tested separately in various shelter and odor combinations. We found that snakes preferred shelter to no shelter quadrants, and most often selected a quadrant if it also had prey odor in the form of lizard or snake scent. However, snakes avoided all quadrants containing mouse (adult) odor. In the second experiment, all three odors plus water were presented simultaneously. We found that snakes showed a preference for lizard odor over the others, but again showed an aversion to mouse odor, even compared to water. The circadian rhythms in both experiments showed generally the same pattern, namely an initial peak in activity, falling off as they entered shelters, but then again increasing even more prominently from lights off until about midnight. Thereafter, activity tapered off so that several hours before lights on in the morning, snakes had generally taken up residence in a shelter. Prey preference correlates with field studies of dietary frequency of lizards, while activity exhibits strong endogenous nocturnal movement patterns. EVERAL factors may influence habitat preference and (Stebbins, 2003), with an abundance of lizards, on which circadian patterns of activity. -

Rediscovery of an Endemic Vertebrate from the Remote Islas Revillagigedo in the Eastern Pacific Ocean: the Clario´N Nightsnake Lost and Found

Rediscovery of an Endemic Vertebrate from the Remote Islas Revillagigedo in the Eastern Pacific Ocean: The Clario´n Nightsnake Lost and Found Daniel G. Mulcahy1*, Juan E. Martı´nez-Go´ mez2, Gustavo Aguirre-Leo´ n2, Juan A. Cervantes-Pasqualli2, George R. Zug1 1 Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, United States of America, 2 Instituto de Ecologı´a, Asociacio´n Civil, Red de Interacciones Multitro´ficas, Xalapa, Veracruz, Me´xico Abstract Vertebrates are currently going extinct at an alarming rate, largely because of habitat loss, global warming, infectious diseases, and human introductions. Island ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to invasive species and other ecological disturbances. Properly documenting historic and current species distributions is critical for quantifying extinction events. Museum specimens, field notes, and other archived materials from historical expeditions are essential for documenting recent changes in biodiversity. The Islas Revillagigedo are a remote group of four islands, 700–1100 km off the western coast of mainland Me´xico. The islands are home to many endemic plants and animals recognized at the specific- and subspecific-levels, several of which are currently threatened or have already gone extinct. Here, we recount the initial discovery of an endemic snake Hypsiglena ochrorhyncha unaocularus Tanner on Isla Clario´n, the later dismissal of its existence, its absence from decades of field surveys, our recent rediscovery, and recognition of it as a distinct species. We collected two novel complete mitochondrial (mt) DNA genomes and up to 2800 base-pairs of mtDNA from several other individuals, aligned these with previously published mt-genome data from samples throughout the range of Hypsiglena, and conducted phylogenetic analyses to infer the biogeographic origin and taxonomic status of this population. -

Bulletins of the Zoological Society of San Diego

BULLETINS OF THE Zoological Society of San Diego No. 24 A Key to the Snakes of the United States Second Edition By C. B. PERKINS Herpetologist, Zoological Society of San Diego SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA AUGUST 20, 1949 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from IMLS LG-70-15-0138-15 https://archive.org/details/bulletinsofzoolo2419unse Zoological Society of San Diego Founded October 6, 1916 BOARD OF DIRECTORS L. M. Klauber, President John P. Scripps, First Vice-President Dr. T. O. Burger, Second Vice-President Fred Kunzel, Secretary Robert J. Sullivan, Treasurer F. L. Annable, C. L. Cotant, Gordon Gray, Lawrence Oliver, L. T. Olmstead, H. L. Smithton, Milton Wegeforth STAFF OF ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN Executive Secretary, Mrs. Belle J . Bcnchley General Superintendent, Ralph J . Virden Veterinarian, Dr. Arthur L. Kelly Supervisors : Grounds, B. E. Helms Birds, K. C. Lint Reptiles , C. B. Perkins Mammals, Howard T. Lee General Curator, Ken Stott, Jr. Education, Cynthia Hare Ketchum Food Concessions, Lisle Vinland Purchasing Agent, Charles W. Kern BULLETINS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF SAN DIEGO No. 24 A KEY TO THE SNAKES OF THE UNITED STATES Second Edition by C. B. Perkins Herpetologist, Zoological Society of San Diego SAN DIEGO. CALIFORNIA August 20, 1949 CONTENTS Introduction to the Second Edition 5 ** . • M Introduction to the Eirst Edition 6 A List of the Snakes of the United States 7 Use of Key 14 Generic Key 15 Synoptic Key 22 Key to Each Genus (Alphabetically Arranged) 24 Drawings Showing Scale Nomenclature. 71-72 Glossary 73 Index 76 Frye & Smith, Ltd., San Diego ——— —— Perkins: A Key to the Snakes of the United States 5 Introduction to Second Edition Since 1940 when the first edition of A KEY TO THE SNAKES OF THE EINITED STATES was published there have been a great many changes in nomenclature in the snakes of the 1 United States. -

Herpetology at the Isthmus Species Checklist

Herpetology at the Isthmus Species Checklist AMPHIBIANS BUFONIDAE true toads Atelopus zeteki Panamanian Golden Frog Incilius coniferus Green Climbing Toad Incilius signifer Panama Dry Forest Toad Rhaebo haematiticus Truando Toad (Litter Toad) Rhinella alata South American Common Toad Rhinella granulosa Granular Toad Rhinella margaritifera South American Common Toad Rhinella marina Cane Toad CENTROLENIDAE glass frogs Cochranella euknemos Fringe-limbed Glass Frog Cochranella granulosa Grainy Cochran Frog Espadarana prosoblepon Emerald Glass Frog Sachatamia albomaculata Yellow-flecked Glass Frog Sachatamia ilex Ghost Glass Frog Teratohyla pulverata Chiriqui Glass Frog Teratohyla spinosa Spiny Cochran Frog Hyalinobatrachium chirripoi Suretka Glass Frog Hyalinobatrachium colymbiphyllum Plantation Glass Frog Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni Fleischmann’s Glass Frog Hyalinobatrachium valeroi Reticulated Glass Frog Hyalinobatrachium vireovittatum Starrett’s Glass Frog CRAUGASTORIDAE robber frogs Craugastor bransfordii Bransford’s Robber Frog Craugastor crassidigitus Isla Bonita Robber Frog Craugastor fitzingeri Fitzinger’s Robber Frog Craugastor gollmeri Evergreen Robber Frog Craugastor megacephalus Veragua Robber Frog Craugastor noblei Noble’s Robber Frog Craugastor stejnegerianus Stejneger’s Robber Frog Craugastor tabasarae Tabasara Robber Frog Craugastor talamancae Almirante Robber Frog DENDROBATIDAE poison dart frogs Allobates talamancae Striped (Talamanca) Rocket Frog Colostethus panamensis Panama Rocket Frog Colostethus pratti Pratt’s Rocket -

Predation on the Black-Throated Sparrow Amphispiza Bilineata

Herpetology Notes, volume 13: 401-403 (2020) (published online on 26 May 2020) Predation on the black-throated sparrow Amphispiza bilineata (Cassin, 1850) and scavenging behaviour on the western banded gecko Coleonyx variegatus (Baird, 1858) by the glossy snake Arizona elegans Kennicott, 1859 Miguel A. Martínez1 and Manuel de Luna1,* The glossy snake Arizona elegans Kennicott, 1859 is Robles et al., 1999a), no specific species have been a nocturnal North American colubrid found from central identified as a prey item until this paper, in which we California to southwestern Nebraska in the United States present evidence of predation on the black-throated and south through Baja California, Aguascalientes, San sparrow Amphispiza bilineata (Cassin, 1850). Luis Potosí and Sinaloa in Mexico (Dixon and Fleet, On 20 September 2017, at around 23:00 h, an 1976). Several species have been identified as prey adult specimen of Arizona elegans was found in the items of this snake (Rodríguez-Robles et al., 1999a) municipality of Hipólito (25.7780 N, -101.4017 W, including the mole Scalopus aquaticus (Linnaeus, 1758) 1195 m a.s.l.), state of Coahuila, Mexico. The snake (Eulipotyphla: Talpidae), the rodents Peromyscus sp. had caught and was in the process of killing and then (Rodentia: Cricetidae), Chaetodipus formosus (Merriam, consuming a small bird (Fig. 1); this act lasted close to 1889), Dipodomys merriami Mearns, 1890, Dipodomys 30 minutes. After completely swallowing its prey, the ordii Woodhouse, 1853, Dipodomys sp., Perognathus snake crawled away to a safe spot under a group of inornatus Merriam, 1889, Perognathus (sensu lato) sp. nearby dead Agave lechuguilla plants. -

Impacts of Off-Highway Motorized Vehicles on Sensitive Reptile Species in Owyhee County, Idaho

Impacts of Off-Highway Motorized Vehicles on Sensitive Reptile Species in Owyhee County, Idaho by James C. Munger and Aaron A. Ames Department of Biology Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725 Final Report of Research Funded by a Cost-share Agreement between Boise State University and the Bureau of Land Management June 1998 INTRODUCTION As the population of southwestern Idaho grows, there is a corresponding increase in the number of recreational users of off-highway motorized vehicles (OHMVs). An extensive trail system has evolved in the Owyhee Front, and several off-highway motorized vehicle races are proposed for any given year. Management decisions by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) regarding the use of public lands for OHMV activity should take account of the impact of OHMV activity on wildlife habitat and populations. However, our knowledge of the impact of this increased activity on many species of native wildlife is minimal. Of particular interest is the herpetofauna of the area: the Owyhee Front includes the greatest diversity of reptile species of any place in Idaho, and includes nine lizard species and ten snake species (Table 1). Three of these species are considered to be "sensitive" by BLM and Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG): Sonora semiannulata (western ground snake), Rhinocheilus lecontei (long-nosed snake), and Crotaphytus bicinctores (Mojave black-collared lizard). One species, Hypsiglena torquata (night snake), was recently removed from the sensitive list, but will be regarded as "sensitive" for the purposes of this report. Off-highway motorized vehicles could impact reptiles in several ways. First, they may run over and kill individuals.