Srtseniornotes, Texts, and Translations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musica Lirica

Musica Lirica Collezione n.1 Principale, in ordine alfabetico. 891. L.v.Beethoven, “Fidelio” ( Domingo- Meier; Barenboim) 892. L.v:Beethoven, “Fidelio” ( Altmeyer- Jerusalem- Nimsgern- Adam..; Kurt Masur) 893. Vincenzo Bellini, “I Capuleti e i Montecchi” (Pavarotti- Rinaldi- Aragall- Zaccaria; Abbado) 894. V.Bellini, “I Capuleti e i Montecchi” (Pavarotti- Rinaldi- Monachesi.; Abbado) 895. V.Bellini, “Norma” (Caballé- Domingo- Cossotto- Raimondi) 896. V.Bellini, “I Puritani” (Freni- Pavarotti- Bruscantini- Giaiotti; Riccardo Muti) 897. V.Bellini, “Norma” Sutherland- Bergonzi- Horne- Siepi; R:Bonynge) 898. V.Bellini, “La sonnanbula” (Sutherland- Pavarotti- Ghiaurov; R.Bonynge) 899. H.Berlioz, “La Damnation de Faust”, Parte I e II ( Rubio- Verreau- Roux; Igor Markevitch) 900. H.Berlioz, “La Damnation de Faust”, Parte III e IV 901. Alban Berg, “Wozzeck” ( Grundheber- Meier- Baker- Clark- Wottrich; Daniel Barenboim) 902. Georges Bizet, “Carmen” ( Verret- Lance- Garcisanz- Massard; Georges Pretre) 903. G.Bizet, “Carmen” (Price- Corelli- Freni; Herbert von Karajan) 904. G.Bizet, “Les Pecheurs de perles” (“I pescatori di perle”) e brani da “Ivan IV”. (Micheau- Gedda- Blanc; Pierre Dervaux) 905. Alfredo Catalani, “La Wally” (Tebaldi- Maionica- Gardino-Perotti- Prandelli; Arturo Basile) 906. Francesco Cilea, “L'Arlesiana” (Tassinari- Tagliavini- Galli- Silveri; Arturo Basile) 907. P.I.Ciaikovskij, “La Dama di Picche” (Freni- Atlantov-etc.) 908. P.I.Cajkovskij, “Evgenij Onegin” (Cernych- Mazurok-Sinjavskaja—Fedin; V. Fedoseev) 909. P.I.Tchaikovsky, “Eugene Onegin” (Alexander Orlov) 910. Luigi Cherubini, “Medea” (Callas- Vickers- Cossotto- Zaccaria; Nicola Rescigno) 911. Luigi Dallapiccola, “Il Prigioniero” ( Bryn-Julson- Hynninen- Haskin; Esa-Pekka Salonen) 912. Claude Debussy, “Pelléas et Mélisande” ( Dormoy- Command- Bacquier; Serge Baudo). 913. Gaetano Doninzetti, “La Favorita” (Bruson- Nave- Pavarotti, etc.) 914. -

We Are Proud to Offer to You the Largest Catalog of Vocal Music in The

Dear Reader: We are proud to offer to you the largest catalog of vocal music in the world. It includes several thousand publications: classical,musical theatre, popular music, jazz,instructional publications, books,videos and DVDs. We feel sure that anyone who sings,no matter what the style of music, will find plenty of interesting and intriguing choices. Hal Leonard is distributor of several important publishers. The following have publications in the vocal catalog: Applause Books Associated Music Publishers Berklee Press Publications Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company Cherry Lane Music Company Creative Concepts DSCH Editions Durand E.B. Marks Music Editions Max Eschig Ricordi Editions Salabert G. Schirmer Sikorski Please take note on the contents page of some special features of the catalog: • Recent Vocal Publications – complete list of all titles released in 2001 and 2002, conveniently categorized for easy access • Index of Publications with Companion CDs – our ever expanding list of titles with recorded accompaniments • Copyright Guidelines for Music Teachers – get the facts about the laws in place that impact your life as a teacher and musician. We encourage you to visit our website: www.halleonard.com. From the main page,you can navigate to several other areas,including the Vocal page, which has updates about vocal publications. Searches for publications by title or composer are possible at the website. Complete table of contents can be found for many publications on the website. You may order any of the publications in this catalog from any music retailer. Our aim is always to serve the singers and teachers of the world in the very best way possible. -

La Sonnambula 3 Content

Florida Grand Opera gratefully recognizes the following donors who have provided support of its education programs. Study Guide 2012 / 2013 Batchelor MIAMI BEACH Foundation Inc. Dear Friends, Welcome to our exciting 2012-2013 season! Florida Grand Opera is pleased to present the magical world of opera to the diverse audience of © FLORIDA GRAND OPERA © FLORIDA South Florida. We begin our season with a classic Italian production of Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème. We continue with a supernatural singspiel, Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Vincenzo Bellini’s famous opera La sonnam- bula, with music from the bel canto tradition. The main stage season is completed with a timeless opera with Giuseppe Verdi’s La traviata. As our RHWIEWSRÁREPI[ILEZIEHHIHERI\XVESTIVEXSSYVWGLIHYPIMRSYV continuing efforts to be able to reach out to a newer and broader range of people in the community; a tango opera María de Buenoa Aires by Ástor Piazzolla. As a part of Florida Grand Opera’s Education Program and Stu- dent Dress Rehearsals, these informative and comprehensive study guides can help students better understand the opera through context and plot. )EGLSJXLIWIWXYH]KYMHIWEVIÁPPIH[MXLLMWXSVMGEPFEGOKVSYRHWWXSV]PMRI structures, a synopsis of the opera as well as a general history of Florida Grand Opera. Through this information, students can assess the plotline of each opera as well as gain an understanding of the why the librettos were written in their fashion. Florida Grand Opera believes that education for the arts is a vital enrich- QIRXXLEXQEOIWWXYHIRXW[IPPVSYRHIHERHLIPTWQEOIXLIMVPMZIWQSVI GYPXYVEPP]JYPÁPPMRK3RFILEPJSJXLI*PSVMHE+VERH3TIVE[ILSTIXLEX A message from these study guides will help students delve further into the opera. -

Cavalleria Rusticana Pagliacci

Pietro Mascagni - Ruggero Leoncavallo Cavalleria rusticana PIETRO MASCAGNI Òpera en un acte Llibret de Giovanni Targioni -Tozzetti i Guido Menasci Pagliacci RUGGERO LEONCAVALLO Òpera en dos actes Llibret i música de Ruggero Leoncavallo 5 - 22 de desembre Temporada 2019-2020 Temporada 1 Patronat de la Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu Comissió Executiva de la Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu President d’honor President Joaquim Torra Pla Salvador Alemany Mas President del patronat Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives, Francesc Vilaró Casalinas Vicepresidenta primera Vocals representants del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives Amaya de Miguel Toral, Antonio Garde Herce Vicepresident segon Vocals representants de l'Ajuntament de Barcelona Javier García Fernández Joan Subirats Humet, Marta Clarí Padrós Vicepresident tercer Vocal representant de la Diputació de Barcelona Joan Subirats Humet Joan Carles Garcia Cañizares Vicepresidenta quarta Vocals representants de la Societat del Gran Teatre del Liceu Núria Marín Martínez Javier Coll Olalla, Manuel Busquet Arrufat Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Vocals representants del Consell de Mecenatge Francesc Vilaró Casalinas, Àngels Barbarà Fondevila, Àngels Jaume Giró Ribas, Luis Herrero Borque Ponsa Roca, Pilar Fernández Bozal Secretari Vocals representants del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Joaquim Badia Armengol Santiago Fisas Ayxelà, Amaya de Miguel Toral, Santiago de Director general -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No. -

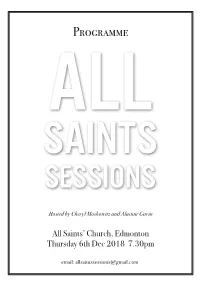

Programme ALL SAINTS SESSIONS

Programme ALL SAINTS SESSIONS Hosted by Cheryl Moskowitz and Alastair Gavin All Saints’ Church, Edmonton Thursday 6th Dec 2018 7.30pm email: [email protected] PROGRAMME Four arias after Vincenzo Bellini Richard Scott Ah! non credea mirarti Aria from “La Sonnambula” by Vincenzo Bellini Elinor Popham - Soprano Alastair Gavin - Electric Piano Reading Richard Ebben? Ne andrò lontana Aria from “La Wally” by Alfredo Catalani Elinor/Alastair 23 Words Cheryl Moskowitz Music by Alastair -------- INTERVAL -------- No One’s Rose A poem sequence by Richard and Cheryl 1) That Word All Over Again after Walt Whitman’s ‘Reconciliation’ - Cheryl 2) le jardin secret (from ‘Soho’) - Richard 3) Lines from ‘Psalm’ by Paul Celan – Cheryl 4) botany4boys - Richard 5) Making Our Own Garden (a Golden Shovel* after Paul Celan’s Psalms) - Cheryl 6) Oh My Soho! (section I) - Richard 7) Creation Story ‘Before there was anything there was…’ - Cheryl 8) Oh My Soho! (section IX) - Richard Music by Elinor & Alastair, concluding with Ma rendi pur content from “Composizioni da Camera” by Vincenzo Bellini * The Golden Shovel is a poetic form devised and given its name by American poet Terrance Hayes (who, with Richard, is also on this year’s TS Eliot prize shortlist). Part cento and part erasure, the form takes a line or a section from a poem by another poet and uses the words from that line or section as the end words in the new poem. The result is an honouring, a response to, and a reinvention of the original. Special thanks to Revd. Stuart Owen for his support and enthusiasm for this venture, Anthony Fisher for his generous donation of sound equipment, and of course to our very special guests Richard Scott and Elinor Popham. -

Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice Through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers

UNDERSTANDING THE LIRICO-SPINTO SOPRANO VOICE THROUGH THE REPERTOIRE OF GIOVANE SCUOLA COMPOSERS Youna Jang Hartgraves Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor William Joyner, Committee Member Silvio De Santis, Committee Member Stephen Austin, Chair of the Division of Vocal Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Hartgraves, Youna Jang. Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 53 pp., 10 tables, 6 figures, bibliography, 66 titles. As lirico-spinto soprano commonly indicates a soprano with a heavier voice than lyric soprano and a lighter voice than dramatic soprano, there are many problems in the assessment of the voice type. Lirico-spinto soprano is characterized differently by various scholars and sources offer contrasting and insufficient definitions. It is commonly understood as a pushed voice, as many interpret spingere as ‘to push.’ This dissertation shows that the meaning of spingere does not mean pushed in this context, but extended, thus making the voice type a hybrid of lyric soprano voice type that has qualities of extended temperament, timbre, color, and volume. This dissertation indicates that the lack of published anthologies on lirico-spinto soprano arias is a significant reason for the insufficient understanding of the lirico-spinto soprano voice. The post-Verdi Italian group of composers, giovane scuola, composed operas that required lirico-spinto soprano voices. -

Guild Gmbh Guild -Historical Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen/TG, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - E-Mail: [email protected] CD-No

Guild GmbH Guild -Historical Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen/TG, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Composer/Track Artists GHCD 2201 Parsifal Act 2 Richard Wagner The Metropolitan Opera 1938 - Flagstad, Melchior, Gabor, Leinsdorf GHCD 2202 Toscanini - Concert 14.10.1939 FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Symphony No.8 in B minor, "Unfinished", D.759 NBC Symphony, Arturo Toscanini RICHARD STRAUSS (1864-1949) Don Juan - Tone Poem after Lenau, op. 20 FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809) Symphony Concertante in B flat Major, op. 84 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor (Orchestrated by O. Respighi) GHCD Le Nozze di Figaro Mozart The Metropolitan Opera - Breisach with Pinza, Sayão, Baccaloni, Steber, Novotna 2203/4/5 GHCD 2206 Boris Godounov, Selections Moussorgsky Royal Opera, Covent Garden 1928 - Chaliapin, Bada, Borgioli GHCD Siegfried Richard Wagner The Metropolitan Opera 1937 - Melchior, Schorr, Thorborg, Flagstad, Habich, 2207/8/9 Laufkoetter, Bodanzky GHCD 2210 Mahler: Symphony No.2 Gustav Mahler - Symphony No.2 in C Minor „The Resurrection“ Concertgebouw Orchestra, Otto Klemperer - Conductor, Kathleen Ferrier, Jo Vincent, Amsterdam Toonkunstchoir - 1951 GHCD Toscanini - Concert 1938 & RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis NBC Symphony, Arturo Toscanini 2211/12 1942 JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Symphony No. 3 in F Major, op. 90 GUISEPPE MARTUCCI (1856-1909) Notturno, Novelletta; PETER IILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840- 1893) Romeo and Juliet -

Spoleto Festival Usa Program History 2017 – 1977

SPOLETO FESTIVAL USA PROGRAM HISTORY 2017 – 1977 Spoleto Festival USA Program History Page 2 Table of Contents, Organized by Year 2017 .................................... 3 2016 .................................... 6 1996 .................................... 76 2015 .................................... 10 1995 .................................... 79 2014 .................................... 13 1994 .................................... 82 2013 .................................... 16 1993 .................................... 85 2012 .................................... 20 1992 .................................... 88 2011 .................................... 24 1991 .................................... 90 2010 .................................... 27 1990 .................................... 93 2009 .................................... 31 1989 .................................... 96 2008 .................................... 34 1988 .................................... 99 2007 .................................... 38 1987 .................................... 101 2006 .................................... 42 1986 .................................... 104 2005 .................................... 45 1985 .................................... 107 2004 .................................... 49 1984 .................................... 109 2003 .................................... 52 1983 .................................... 112 2002 .................................... 55 1982 .................................... 114 2001 ................................... -

In Concert the Hologram Tour Callas in Concert the Hologram Tour 80.26

CALLAS IN CONCERT THE HOLOGRAM TOUR CALLAS IN CONCERT THE HOLOGRAM TOUR 80.26 Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) 1 La gazza ladra, Overture (excerpt) 2.55 Philharmonia Orchestra · Carlo Maria Giulini Charles Gounod (1818-1893) 2 Roméo et Juliette, Act 1: Juliet’s Waltz. “Ah! Je veux vivre dans ce rêve” (Juliette) 3.40 Maria Callas Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion Française · Georges Prêtre Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) 3 Macbeth, Act 1: Letter Scene. “Nel dì della vittoria ... Vieni! t’affretta” (Lady Macbeth, Chorus) 7.48 Maria Callas Philharmonia Chorus & Orchestra · Nicola Rescigno Georges Bizet (1838-1875) Carmen 4 Overture 2.17 5 Act 1: Habanera. “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” (Carmen, Chorus) 4.22 6 Act 3: Card Aria. “Mêlons! Coupons!” (Frasquita, Mercédès, Carmen) 6.56 Carmen Maria Callas Frasquita Nadine Sautereau · Mercédès Jane Berbié Orchestre de l’Opéra National de Paris · Georges Prêtre Giuseppe Verdi Macbeth 7 Act 3: Ballabile (Valzer) 3.11 New Philharmonia Orchestra · Riccardo Muti 8 Act 4: Sleepwalking Scene. “Una macchia è qui tuttora!” (Lady Macbeth) 11.17 Maria Callas Philharmonia Orchestra · Nicola Rescigno Alfredo Catalani (1854-1893) 9 La Wally, Act 1: “Ebben?... Ne andrò lontana”* (Wally) 4.51 Maria Callas Philharmonia Orchestra · Tullio Serafin 2 Ambroise Thomas (1811-1896) 10 Hamlet, Act 4: Mad Scene. “À vos jeux, mes amis … Partagez-vous mes fleurs” (Ophélie) 10.24 Maria Callas Philharmonia Orchestra · Nicola Rescigno Amilcare Ponchielli (1834-1886) La Gioconda, Act 4: 11 Prelude 5.04 12 “Suicidio!” (Gioconda) -

SOCIAL STUDIES: Historical Settings for Opera/ Becoming the Librettist

SOCIAL STUDIES: Historical Settings for Opera/ Becoming the Librettist Students will Read for information and answer questions Research an event, civilization, landmark, or literary work as a source for a setting Write a brief setting and story as the basis for an opera Copies for Each Student: Tosca Synopsis, “What is a Librettist”, “Our Librettists, Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica“, Activity Worksheet Copies for the Teacher: Social Studies lesson plan, Tosca Synopsis, “What is a Librettist”, “Our Librettists, Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica“, Activity Worksheet, Answer Key Getting Ready Prepare internet access for possible research for guided practice or group work. Gather pens, pencils and additional writing paper as needed for your students. Introduction Explain to your students that a commissioned work is a piece of visual or performing art created at the request and expense of someone else. Begin the lesson by explaining to your students that composers and librettists work closely to create an opera. Have the students discuss what they believe the research duties of a librettist are. You may want to guide the discussion so that the students begin to understand the historic and cultural influence on opera and art as a whole. Have your students read the synopsis, “What is a Librettist”, and “Our Librettists, Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica”. Give each student a copy of the Activity Worksheet or display it on a screen. Give an overview of the assignment, and point out the information your students are expected to research and write about. To align with Texas TEKS, you may provide and tailor research topics according to your grade level: 6th Grade: Societies of the contemporary world. -

The Recordings of Beniamino Gigli His Master's Voice and Victor

The Recordings of Beniamino Gigli His Master's Voice and Victor Version 2.0 (Updated Aug 12, 2020) JOHN R. BOLIG Mainspring Press Free edition for personal, non-commercial use only © 2020 by John R. Bolig. All rights are reserved. All photographs are from the G. G. Bain Collection in the Library of Congress, and are in the public domain. This publication is protected under U.S. copyright law as a work of original scholarship. It may downloaded free of charge for personal, non-commercial use only. This work may not be duplicated, altered, or distributed in any form — printed, digital, or otherwise — including (but not limited to) conversion to digital database or e-book formats, or distribution via the Internet or other networks. Sale or other commercial use of this work is prohibited. Unauthorized use, whether or not for monetary gain, will be addressed under applicable laws. Publication rights are assigned to Mainspring Press LLC. For information on licensing this work, or for permission to reproduce excerpts exceeding customary fair-use standards, please contact the publisher. Mainspring Press LLC PO Box 631277 Littleton CO 80163-1277 www.mainspringpress.com / [email protected] The Commercial Recordings of Beniamino Gigli By John R. Bolig Preface and Introduction Beniamino Gigli was the first of many tenors who was described as “The next Caruso.” His career began shortly before the death of the great tenor, and he was a major attraction at a number of major opera houses, and in concert, for the next 25 years. He was also featured in a number of motion pictures, and especially as a recording artist.