John Galt, by R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Guide to Huron County Hiking

Your Guide to Huron County Hiking HikingGuide www.ontarioswestcoast.caPage 1 Huron County’s Hiking Experience Welcome to Huron County . Ontario’s West Coast! Discover the enjoyment of the outdoors for pleasure and improved health through walking, cycling and cross country skiing. Located in Southwestern Ontario, Huron County offers trail enthusiasts of all ages and skill levels a variety of terrains from natural paths to partially paved routes. Come and explore! Huron County is a vacation destination of charm, culture, beauty and endless possibilities! Contact the address or number below and ask for your free copy of the Ontario’s West Coast Vacation Guide to help plan your hiking adventure! For the outdoor recreation enthusiast, Huron County also offers a free Cycling Guide and a Fish/Paddle brochure. For information about these and additional conservation areas and heritage walking tours, contact us. GEORGIAN BAY Owen Sound LAKE SIMCOE LAKE HURON Barrie Kincardine HURON COUNTY Wingham Goderich Blyth Brussels Toronto Clinton Bayfield Seaforth Kitchener/ Zurich Hensall Waterloo Guelph LAKE Exeter Stratford Grand Bend ONTARIO MICHIGAN Niagara Falls, Hamilton USA Trail User’s Code Niagara Falls Port Huron London Sarnia LAKE ST. CLAIR Detroit Windsor LAKE ERIE Kilometers 015 0203040 For your complete Huron County travel information package contact: [email protected] or call 1-888-524-8394 EXT. 3 County of Huron, 57 Napier St., Goderich, Ontario • N7A 1W2 Publication supported by the County of Huron Page 2 Printed in Canada • Spring 2016 (Sixth Edition) How To Use This Guide This Guide Book is designed as a quick and easy guide to hiking trails in Huron County. -

Curriculum Vitae

1 Academic Curriculum Vitae Dr. Sharon-Ruth Alker Current Position 2020 to date Chair of Division II: Humanities and Arts 2018 to date Mary A. Denny Professor of English and General Studies 2017 to date Professor of English and General Studies 2017 to 2019 Chair of the English Department, Whitman College 2010 to 2017 Associate Professor of English and General Studies Whitman College 2004 to 2010 Assistant Professor of English and General Studies Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA. Education *University of Toronto – 2003-2004 Postdoctoral Fellowship * University of British Columbia - 1998 to 2003 - PhD. English, awarded 2003 Gendering the Nation: Anglo-Scottish relations in British Letters 1707-1830 * Simon Fraser University - 1998 MA English * Simon Fraser University - 1996 BA English and Humanities Awards 2020 Aid to Scholarly Publications Award, Federation for Humanities and Social Sciences (Canadian). This is a peer-reviewed grant. For Besieged: The Post War Siege Trope, 1660-1730. 2019 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Alasdair Padman on a John Galt edition. 2018 Whitman Abshire Grant to work with student Nick Maahs on a James Hogg 2 website 2017 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Esther Ra on James Hogg’s Uncollected Works and an edition of John Galt’s Sir Andrew Wylie of that Ilk 2017 Whitman Abshire Grant to work with student Esther Ra on James Hogg’s Manuscripts 2016 Co-organized a conference that received a SSHRC Connection Grant to organize the Second World Congress of Scottish Literatures. Conference was in June 2017. 2015 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Nicole Hodgkinson on chapters of the military siege monograph. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

The Effect of School Closure On

The Business of Writing Home: Authorship and the Transatlantic Economies of John Galt’s Literary Circle, 1807-1840 by Jennifer Anne Scott M.A. (English), Simon Fraser University, 2006 B.A. (Hons.), University of Winnipeg, 2005 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Jennifer Anne Scott 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2013 Approval Name: Jennifer Anne Scott Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (English) Title of Thesis: The Business of Writing Home: Authorship and the Transatlantic Economies of John Galt’s Literary Circle, 1807-1840. Examining Committee: Chair: Jeff Derksen Associate Professor Leith Davis Senior Supervisor Professor Carole Gerson Senior Supervisor Professor Michael Everton Supervisor Associate Professor Willeen Keough Internal Examiner Associate Professor Department of History Kenneth McNeil External Examiner Professor Department of English Eastern Connecticut State University Date Defended/Approved: May 16, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This dissertation examines nineteenth-century Scottish author John Galt’s dialogue with the political economics of his time. In particular, I argue that both in his practices as an author and through the subject matter of his North American texts, Galt critiques and adapts Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776). Galt’s critique of Smith becomes evident when we examine the relationship between his engagement with political economy in his most important North American literary texts and his overt political interests, specifically those concerning transatlantic land development and colonial expansion, a project he pursued with the Canada Company. In Chapter One, I examine John Galt’s role with the Canada Company. -

The Argosy – Bmds ‐ 1891

The Argosy – BMDs ‐ 1891 SATURDAY JANUARY 3 1891 P 4 COL Birth RITCHIE ‐ At St Andrew's Manse, Georgetown, on January 2nd, the wife of the Rev. W.B. Ritchie, of a Daughter. Married TAYLOR‐DOUGALL ‐ At Ebenezer Church, West Coast, Demerara, on 27th December, 1890, by the Rev. James Millar, Minister of the parish, assisted by the Rev. J.L. Green, Henry John Taylor, eldest son of Major William Taylor, R.A., Renfrewshire, N.B., to Anna Rebecca Stuart., eldest daughter of David Dougall, of Pln. Blankenburg. Died CHOPPIN ‐ On 27th December, 1890, at Blankenburg, West Coast, Demerara, Gerald Crosby, aged 28 years, 3rd Class Clerk in the Government Land's Dept. SPEIRS ‐ At the Manse, New Amsterdam, on the 31st ult., Susan Walker, wife of the Rev. James Speirs. SATURDAY JANUARY 10 1891 P 4 COL 1 Birth GETTING ‐ On December 30th, 1890, at Kaieteur College Rd., Norwood, London, the wife of Henry F. Getting, of a Son. Died DE PRADEL ‐ At Paris, on the 16th December, 1890, of Diphtheria, George Eugene, son of Dr. and Mme. De Pradel, aged 2 years and 9 months. FRANCIS ‐ On the morning of the 8th instant, at Lot 189, Upper Charlotte Street, Alfred Cyril, infant son of Charles and Winnie Francis. Aged 9 weeks. SATURDAY JANUARY 17 1891 P 4 COL 1 Married CHAPMAN‐FARLEY ‐ On the 13th instant, at Vryheid's Lust Church, by the Rev. Thomas Slater, Joseph Ivelaw Chapman, to Shirley Isabel, youngest daughter of the late W.H.N.Farley. SATURDAY JANUARY 24 1891 P 4 COL 1 Birth IRVING ‐ At New Amsterdam, on the 20th instant, the wife of M.H.C. -

Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth- Century Novel

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1965 Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth- Century Novel. James M. Keech Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Keech, James M. Jr, "Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth-Century Novel." (1965). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1081. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1081 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been - microfilmed exactly as received 66-737 K E E C H , Jr., James M., 1933- THREE-DECKERS AND INSTALLMENT NOVELS: THE EFFECT OF PUBLISHING FORMAT UPON THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOVEL. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1965 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THREE-DECKERS AMD INSTALLMENT NOVELS: THE EFFECT OF PUBLISHING FORMAT UPON THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOVEL A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulflllnent of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English hr James M. Keech, Jr. B.A., University of North Carolina, 1955 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1961 August, 1965 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to express my deepest appreciation to the director of this study, Doctor John Hazard Wildman. -

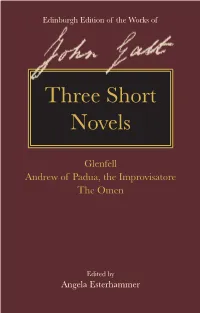

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: a History of Corporate Ownership in Canada

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: A History of Corporate Governance around the World: Family Business Groups to Professional Managers Volume Author/Editor: Randall K. Morck, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-53680-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/morc05-1 Conference Date: June 21-22, 2003 Publication Date: November 2005 Title: The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Author: Randall Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Tian, Bernard Yeung URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10268 1 The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Randall K. Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Y. Tian, and Bernard Yeung 1.1 Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century, large pyramidal corporate groups, controlled by wealthy families or individuals, dominated Canada’s large corporate sector, as in modern continental European countries. Over several decades, a large stock market, high taxes on inherited income, a sound institutional environment, and capital account openness accompa- nied the rise of widely held firms. At mid-century, the Canadian large cor- porate sector was primarily freestanding widely held firms, as in the mod- ern large corporate sectors of the United States and United Kingdom. Then, in the last third of the century, a series of institutional changes took place. These included a more bank-based financial system, a sharp abate- Randall K. Morck is Stephen A. Jarislowsky Distinguished Professor of Finance at the University of Alberta School of Business and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

HERITAGE Walking & Driving Tours

Bluewater HERITAGE Walking & Driving Tours STANLEY TOWNSHIP ‘Stagecoach Stops Produced by the Municipality of Bluewater Heritage Advisory Committee in 2018, with the generous assistance of the Huron Heritage Fund. This tour will take approximately 1 hour at a comfortable driving pace. Municipality of WELCOME! This is a Driving Tour. TOUR ETIQUETTE: Please respect people’s privacy. Many of the places on the tour are private businesses or residences and their inclusion is meant to highlight their history or architecture. Their presence on the tour does not include permission to enter the properties, unless they’re public spaces or businesses offering public services. Keep in mind that construction and other temporary events may involve the need to adjust your tour route; please keep a Huron County map in the car (available at tourist information centres and libraries) or have your GPS (app or device) at hand to help make any necessary detours. Water and picnic supplies are also nice to have along for a tour in the country, not to mention a cooler for refreshments or to store the goodies you’ll find at the farm markets, local breweries and cider shops along the way. Don’t stress if you get lost ... sometimes you find the best treasures that way! Just remember: in this area, the lake is always west. That’s why we have such great sunsets! So! Let’s go on a driving tour of Stanley Township’s stagecoach stops. Along the way, we’ll point out some interesting sites to see and make sure to recommend at least one stop for ice cream for those summertime explorers. -

Weekly Update

Weekly update Rotary Club of Etobicoke District Governor: Ted Koziel RI President: Sakuji Tanaka Week November 07, 2012 Board 2011 - 2012 President: Hugh Williams, Secretary: Ron Miller, Treasurer: Don Edwards November 14, 2012: Speaker – TBA has been active in Community activities; Chair of Stratford Board of Park Management, President of the Stratford Horticultural Society; Chaired the “Save City Hall” movement that Today’s Speakers - Lutzen saved their historic City Hall; was and has Riedstra & Reg White Fryfogel & rejoined the Perth County Historical Foundation Canada Company who are the owners of the Fryfogel Tavern; and is the current Chair of the newly formed committee called the Friends of the Fryfogel Arboretum. He is also an active member of the Rotary Club of Stratford. Lutzen began by giving some background on the Fryfogel Tavern. Located at the edge of Highway 7/8, which constitutes the former Huron Road, Fryfogel's Nigel Brown introduced Lutzen Riedstra and Tavern recalls the early settlement pattern of Reg White. Lutzen retired after 28 years as the the Perth County. It was along this road that archivists for the Stratford-Perth Archives (the settlement in the area first began to spread archives for City of Stratford and Perth out, therefore placing it amidst one of the County). He is historian and has written two municipality's most historic areas. Bordering a histories and numerous articles. Since retiring brook, which was undoubtedly a factor in the he has been teaching part-time at the Master of tavern's placement, the site also features a Library and Information Studies at University of wooded perimeter and grassed yard reflecting Western Ontario. -

John Galt 1779 - 1839 1132 James Galt Layout 1 29/03/2012 17:32 Page 2

1132 James Galt_Layout 1 29/03/2012 17:32 Page 1 John Galt 1779 - 1839 1132 James Galt_Layout 1 29/03/2012 17:32 Page 2 John Galt 1779 - 1839 John Galt was born in Irvine in 1779, the son of a sea captain who traded with the West Indies. In 1789 the family moved to Greenock and much of Galt’s fiction draws from the localities of the west coast of Scotland where he spent his youth. He was a sickly child and much of his time was spent listening to the traditional tales of his mother and the local women of Greenock, an influence that feeds into Galt’s gift for storytelling and his acute ear for regional dialect. John Galt was possessed of a pragmatic as well as an imaginative turn of mind. He had a keen interest in business and politics and always maintained that he regarded writing as a secondary profession. From 1796 - 1804 Galt worked as a junior justice clerk in Greenock before setting off for London on a sudden impulse of restless ambition. Here he studied political economy and commercial history and practise but failed to really make his mark on the business world despite several promising ventures. Around the age of twenty-four Galt began writing. He experimented in verse but was an inferior poet. Several of his essays, however, were published and his writing at this time demonstrates his early interest in politics and the colonies, particularly Canada which had long captured his imagination. 1132 James Galt_Layout 1 29/03/2012 17:32 Page 3 In 1809 Galt spent a period of time travelling on the Mediterranean and it was here that he made his acquaintance with Lord Byron who was to become the subject of his acclaimed biography The Life of Byron in 1830. -

Paisley Pamphlets 1739

PAISLEY PAMPHLETS 1739 – 1893 The 'Paisley Pamphlets' are a collection of ephemera rich in social history covering the period 1739 - 1893. Ephemera are items of collectible memorabilia in written or printed form which had only a short period of usefulness or popularity. The pamphlets cover a range of topics, chiefly politics and religion. To make it easy for you to search, we have combined the indexes for all the volumes into this one volume. On the next page we will give you guidance on how to search the index. Searching the Paisley Pamphlets index ➢ Browse pages simply by scrolling up and down ➢ If you are viewing the index online you can click ctrl + f on your keyboard to bring up the search box where you can enter the term you want to search for If you have saved a copy of the PDF to your tablet or PC, and are using Adobe Acrobat Reader to view it, you can use the search tool. Just click on it and enter the term you want to search for. ➢ Your results will start to appear beneath the search box. You can look at any of the entries by clicking on it. ➢ Using either search tool, your results will appear as highlighted text. You can just work through all the matches to see if any of the records are of use to you. Tips! If you are unsure about the spelling or the wording which has been used, you can search under just a few letters e.g. searching “chem” will give you results including chemist, chemistry, chemicals, etc.