Poospiza Nigrorufa/Whitii)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Argentina (Custom Tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour Leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-Guided by Sam Woods

Northwest Argentina (custom tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-guided by Sam Woods Trip Report by Andrés Vásquez; most photos by Sam Woods, a few by Andrés V. Elegant Crested-Tinamou at Los Cardones NP near Cachi; photo by Sam Woods Introduction: Northwest Argentina is an incredible place and a wonderful birding destination. It is one of those locations you feel like you are crossing through Wonderland when you drive along some of the most beautiful landscapes in South America adorned by dramatic rock formations and deep-blue lakes. So you want to stop every few kilometers to take pictures and when you look at those shots in your camera you know it will never capture the incredible landscape and the breathtaking feeling that you had during that moment. Then you realize it will be impossible to explain to your relatives once at home how sensational the trip was, so you breathe deeply and just enjoy the moment without caring about any other thing in life. This trip combines a large amount of quite contrasting environments and ecosystems, from the lush humid Yungas cloud forest to dry high Altiplano and Puna, stopping at various lakes and wetlands on various altitudes and ending on the drier upper Chaco forest. Tropical Birding Tours Northwest Argentina, Nov.2015 p.1 Sam recording memories near Tres Cruces, Jujuy; photo by Andrés V. All this is combined with some very special birds, several endemic to Argentina and many restricted to the high Andes of central South America. Highlights for this trip included Red-throated -

Listas De Aves 2019

List of bird of CUSCO BIRDING - CUSCO 3399 m.a.s.l N° ENGLISH NAME NOMBRE CIENTIFICO 1 Alder Flycatcher Empidonax alnorum 2 American Golden-Plover Pluvialis dominica 3 American Kestrel Falco sparverius 4 Amethyst-throated Sunangel Heliangelus amethysticollis 5 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 6 Andean Cock-of-the-rock Rupicola peruvianus 7 Andean Condor Vultur gryphus 8 Andean Duck Oxyura ferruginea 9 Andean Flicker Colaptes rupicola 10 Andean Goose Oressochen melanopterus 11 Andean Guan Penelope montagnii 12 Andean Gull Chroicocephalus serranus 13 Andean Hillstar Oreotrochilus estella 14 Andean Lapwing Vanellus resplendens 15 Andean Motmot Momotus aequatorialis 16 Andean Negrito Lessonia oreas 17 Andean Parakeet Bolborhynchus orbygnesius 18 Andean Solitaire Myadestes ralloides 19 Andean Swallow Orochelidon andecola 20 Andean Swift Aeronautes andecolus 21 Andean Tinamou Nothoprocta pentlandii 22 Andean Tit-Spinetail Leptasthenura andicola 23 Aplomado Falcon Falco femoralis 24 Ash-breasted Sierra-Finch Phrygilus plebejus 25 Ash-breasted Tit-Tyrant Anairetes alpinus 26 Ashy-headed Tyrannulet Phyllomyias cinereiceps 27 Azara's Spinetail Synallaxis azarae 28 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii 29 Bananaquit Coereba flaveola 30 Band-tailed Fruiteater Pipreola intermedia 31 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas fasciata 32 Band-tailed Seedeater Catamenia analis 33 Band-tailed Sierra-Finch Phrygilus alaudinus 34 Band-winged Nightjar Systellura longirostris 35 Bank Swallow Riparia riparia 36 Bar-bellied Woodpecker Veniliornis nigriceps 37 Bare-faced -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection. -

Neotropical Birding 24 2 Neotropical Species ‘Uplisted’ to a Higher Category of Threat in the 2018 IUCN Red List Update

>> FEATURE RED LIST 2018 The 2018 IUCN Red List in the Neotropics James Lowen, Hannah Wheatley, Claudia Hermes, Ian Burfield and David Wege Neotropical Birding 21 featured a summary of the key implications for the Neotropics of the 2016 IUCN Red List for birds. This article briefs readers on the main changes from the 2018 update. s part of its role as the IUCN Red List BirdLife’s Red List team updated the Authority for birds, BirdLife International information available for roughly 2,300 species A is responsible for assessing the global worldwide. Globally, this resulted in changes to conservation status of each of the world’s 11,000 the categorisation of 89 species; 58 species were or so bird species, allocating each to a category ‘uplisted’ to a higher category of threat, whilst ranging from Least Concern to Extinct. The latest roughly half that number – 31 species – were update was published in November 2018 (BirdLife ‘downlisted’. In the Neotropics, 13 species were International 2018). Although much more modest uplisted (Fig. 2) and slightly more – 18 – were in reach than the comprehensive update carried downlisted (Fig. 5). Now let’s take a closer look at out in 2016, whose Neotropical dimension was the individual changes, largely using information discussed in Symes et al. (2017), the 2018 revamp made available on BirdLife’s ‘Globally Threatened contains a suite of interesting changes for species Bird Forums’ (8 globally-threatened-bird- occurring in the Neotropical Bird Club region that forums.birdlife.org). Is the picture quite as rosy as are worth drawing to readers’ collective attention. -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report CENTRAL PERUVIAN ENDEMICS: THE HIGH ANDES 2018 May 31, 2018 to Jun 16, 2018 Dan Lane & Dave Stejskal For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. One of the most-wanted birds of the tour was the Golden-backed Mountain-Tanager. This Peruvian endemic is found in a small area of high forest in the eastern Peruvian Andes, including Bosque Unchog. We had great looks at this beauty at a spot very near our camp. Photo by guide Dave Stejskal. Field Guides has been guiding birding tours to Peru since our inception. Indeed, the first tour ever run at Field Guides back in June of 1985 was to Peru! Since then, we've set up quite a number of diverse offerings to this wonderful, rich country over the years, from the border with Ecuador in the north, south to the Bolivian border, and east into the wilds of western Amazonia. Our most popular offerings seem to be in the northern Andes and the southern Andes (think Marvelous Spatuletail/Long-whiskered Owlet and Machu Picchu/Abra Malaga), but the the vast central Andes region has been relatively neglected all of these years. This expansive region in Peru (in Ancash, Huánuco, Pasco, and Junín departments) holds a high percentage of the total number of Peruvian endemics, a number of which can't be seen anywhere else in the world! But you've really got to want to see these birds in the intensely scenic, high Andean settings where they're found, in order to get through the high elevation hiking, camping (only two nights), and cold temperatures that are endemic to this itinerary. -

Birds from Cáceres, Mato Grosso: the Highest Species Richness Ever Recorded in a Brazilian Non-Forest Region

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 24(2), 137-167 ARTICLE June 2016 Birds from Cáceres, Mato Grosso: the highest species richness ever recorded in a Brazilian non-forest region Leonardo Esteves Lopes1,8, João Batista de Pinho2, Aldo Ortiz2, Mahal Massavi Evangelista3, Luís Fábio Silveira4,6, Fabio Schunck4,5,6 and Pedro Ferreira Develey7 1 Laboratório de Biologia Animal, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Campus Florestal, Rodovia LMG 818, km 6, s/n, CEP 35690-000, Florestal, MG, Brazil. 2 Núcleo de Estudos Ecológicos do Pantanal, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Avenida Fernando Corrêa da Costa, s/n, Boa Esperança, CEP 78060-900, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil. 3 Faculdade de Ciências Biólogicas, Universidade de Cuiabá, Rua Manoel José de Arruda, 3100, Jardim Europa, CEP 78065-900, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil. 4 Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Nazaré, 481, Ipiranga, CEP 04263-000, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 5 Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos-CBRO, Brazil. 6 Pós-Graduação, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão, Travessa 14, 101, Cidade Universitária, CEP 05508-090, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 7 Sociedade para a Conservação das Aves do Brasil - SAVE, Rua Fernão Dias, 219 cj. 2, Pinheiros, CEP 05427-010, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 8 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 30 January 2016. Accepted on 04 April 2016. ABSTRACT: Them unicipality of Cáceres. Mato Grosso state, Brazil, lies in a contact zone between three semi-arid to arid ecoregions: the Chiquitano Dry Forests, the Cerrado and the Pantanal. -

Climate Explains Recent Population Divergence, Introgression

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/439265; this version posted October 22, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Climate explains recent population divergence, introgression and persistence in tropical 2 mountains: phylogenomic evidence from Atlantic Forest warbling finches 3 4 Fábio Raposo do Amaral1†*, Diego F. Alvarado-Serrano2†, Marcos Maldonado-Coelho1, Katia 5 C. M. Pellegrino1, Cristina Y. Miyaki3, Julia A. C. Montesanti1, Matheus S. Lima-Ribeiro4, 6 Michael J. Hickerson2, Gregory Thom3 7 8 1 Universidade Federal de São Paulo. Departamento de Ecologia e Biologia Evolutiva. Rua 9 Professor Artur Riedel, 275, Diadema, SP, 09972-270, Brazil. 10 2 Biology Department, City College of New York, New York, NY 10031, USA 11 3 Universidade de São Paulo, Departamento de Genética e Biologia Evolutiva. Rua do Matão, 12 277, Cidade Universitária, São Paulo, SP, 05508-090, Brazil. 13 4 Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Campus Jataí, Jataí, 14 GO, Brasil 15 † These authors contributed equally to this study 16 * To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] 17 18 Running title: Isolation and contact in Atlantic Forest mountains 19 Keywords: Atlantic Forest biogeography, cold-adapted birds, demographic history, 20 ultraconserved elements 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/439265; this version posted October 22, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

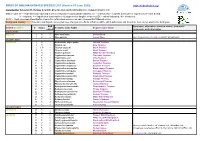

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4Th to 25Th September 2016

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4th to 25th September 2016 Marañón Crescentchest by Dubi Shapiro This tour just gets better and better. This year the 7 participants, Rob and Baldomero enjoyed a bird filled trip that found 723 species of birds. We had particular success with some tricky groups, finding 12 Rails and Crakes (all but 1 being seen!), 11 Antpittas (8 seen), 90 Tanagers and allies, 71 Hummingbirds, 95 Flycatchers. We also found many of the iconic endemic species of Northern Peru, such as White-winged Guan, Peruvian Plantcutter, Marañón Crescentchest, Marvellous Spatuletail, Pale-billed Antpitta, Long-whiskered Owlet, Royal Sunangel, Koepcke’s Hermit, Ash-throated RBL Northern Peru Trip Report 2016 2 Antwren, Koepcke’s Screech Owl, Yellow-faced Parrotlet, Grey-bellied Comet and 3 species of Inca Finch. We also found more widely distributed, but always special, species like Andean Condor, King Vulture, Agami Heron and Long-tailed Potoo on what was a very successful tour. Top 10 Birds 1. Marañón Crescentchest 2. Spotted Rail 3. Stygian Owl 4. Ash-throated Antwren 5. Stripe-headed Antpitta 6. Ochre-fronted Antpitta 7. Grey-bellied Comet 8. Long-tailed Potoo 9. Jelski’s Chat-Tyrant 10. = Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Yellow-breasted Brush Finch You know it has been a good tour when neither Marvellous Spatuletail nor Long-whiskered Owlet make the top 10 of birds seen! Day 1: 4 September: Pacific coast and Chaparri Upon meeting, we headed straight towards the coast and birded the fields near Monsefue, quickly finding Coastal Miner. Our main quarry proved trickier and we had to scan a lot of fields before eventually finding a distant flock of Tawny-throated Dotterel; we walked closer, getting nice looks at a flock of 24 of the near-endemic pallidus subspecies of this cracking shorebird. -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Bolivia's Avian Riches 2018 Sep 7, 2018 to Sep 23, 2018 Dan Lane and Micah Riegner For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The cloud forest on the eastern side of the Andes supports some of the richest birdlife in the world. Photo by guide Micah Riegner. Bolivia is one of those well-kept secrets; in the birding world it tends to be eclipsed by Ecuador, Peru and Brazil, whose feeder-adorned lodges attract birders worldwide. That said, for those who are up for some adventure, Bolivia is a fabulous, fabulous place to bird. The range of habitats crammed within its borders is truly astounding. From moss-laden Yungas ridgetops dripping with ferns and orchids on the eastern flank of the Andes to steep cactus gorges in their rain shadow—and from hot Chiquitania lowlands around Santa Cruz, to the frigid Puna at 4700 m where ground-tyrants and diuca- finches frolic through Ichu bunch grass, to the colossal sandstone massifs of Refugio Los Volcanes towering over the southernmost fingers of Amazonia, Bolivia is truly a birder’s paradise. In our 2-week pursuit of antpittas, canasteros, sunbeams and salteñas, we traversed these awesome landscapes and encountered some of the country's most sought-after avifauna. We were bedazzled by the turquoise rump of the endemic Black-hooded Sunbeam, baffled by a Giant Antshrike (a thamnophilid, the size of a Sharp-shinned Hawk!), and bewildered by Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe, who eke out existence in the barren, wind-swept Puna. -

Brazil Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna

Southeast Brazil Atlantic Rainforest and savanna 17 September – 4 October 2010 Tour leader: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Photo right: Red-necked Tanager This is an ambitious tour; we cover a lot of ground (over 3500 km) yet see a heck of a lot of birds, leaving very little behind by the end of the 18 days. This year’s version was once again superb and very smooth, with decent weather, a small, friendly group, and its share of avian surprises. A slight itinerary modification due to the temporary closure of Caraça may have cost us Maned Wolf, but it did pay extra dividends in allowing us to successfully target Rio de Janeiro Antbird, the first time we’ve ever had it on this tour. Speaking of antbirds, they were perhaps the most memorable feature of this tour; Southeast Brazil features the most spectacular and colorful members of this huge neotropical family, and we saw a tour record 34 species, missing nothing of note, and everyone saw each of them well! That will be tough to surpass on future tours. The Canastra area was exceptionally good this year; we nailed the mergansers within minutes on our first morning, allowing us to enjoy birding there with a lot less stress. A recent burn in upper grasslands made it a great year for the usually tough Campo Miner, and a surprise Capped Seedeater was a very welcome addition to the tour. 17 September : Fortunately, everyone arrived in São Paulo on schedule, and we quickly headed out of this gigantic metropolis to Intervales State Park, a few hours to the southwest. -

SOUTHERN BRAZIL 27 March – 11 April 2018 by #Epatrialbirding

Group of Red-spectacled Amazon searching for seeds in the Araucaria tree (Eduardo Patrial) SOUTHERN BRAZIL 27 March – 11 April 2018 By #epatrialbirding Despite being a tour right at the beginning of autumn - not the richest time to visit the Atlantic Forest - this 2018 Southern Brazil trip was still fully packed with birds with over four hundred (410) species recorded. This is a tour that usually surprises participants by offering a very scenic route in the country in some of most diverse and singular areas from the whole Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Besides achieving most of the regional and localised endemics present in southern São Paulo and in the Brazilian South region, the tour this time of year also revealed the singular seeding period of the Araucaria tree in the southern plateaus together with the spectacular migration of Red- spectacled Amazon, a refined touch for the trip. We recorded a total of fifty three (53) genuine Brazilian endemic species and over a hundred and thirty (137) endemics from the biome Atlantic Forest. On this fabulous trip starting from Guarulhos (São Paulo) international airport in Brazil, we first visited the mighty a Intervales State Park at Serra do Paranapiacaba, a large branch of Serra do Mar in southern São Paulo which is part of the largest continuous Atlantic Forest remnant in the country. The park offers good facilities and in three full days its dense montane and bamboo rich Atlantic Forest was responsible for nearly half of the checklist. In this bird paradise full of endemic #epatrialbirding –