The Road Ahead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record-House. March 20

'1718 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. MARCH 20, By Mr. HILL: The petitions of W. Wrede and 100 others, of F. CHANGES OF REFERENCES. Duok and 100 others, of John Mason and others, of J. W. Berry and Changes of references of petitions were made, under the rule, as 100 others, citizens of Defiance and Williams Counties, and of Cas follows: per Kahl and 100 others, citizens of the sixth district of Ohio, soldiers The petition of W. B. Wellgwood, vice-chancellor of the National of the United States Army, engaged in the late war, for the early University-from the Committee on Appropriations to the Commit passage of a law providing for the payment of the difference between tee on Education and Labor. the value of the greenbacks, in which they were paid for their serv The petitions of Eban B. Grant and others; of Bernard McCormick ices, and the value of gold at the time of payment-to the Commit and 6 other~ of C. J. Poore and 122 others, citizens of Michigan; of tee on Military Affairs. citizens of l.Jolville, Washington Territory, and of citizens of Wash 1 By Mr. JOSEPH J. MARTIN: The petition of the publisher of the ington Territory-from the Committee on Appropriations to the Com Falcon, Elizabeth City, North Carolina, that materials used in mak mittee on ~tary Affairs. ing paper be placed on the free µst, and for the reduction of the duty on printing-paper-to the Committee on Ways and Means. By Mr. McKENZIE: The petitions of J.M. Nicholls and Charles W. -

REGISTER \ 1934 ¿ F I VOLUME 10 * Í/A//TED % NUMBER 217

S o ^ uttebaT V 7 I SCRIPTA I As I MANET I \JI REGISTER \ 1934 ¿ f i VOLUME 10 * Í/A//TED % NUMBER 217 Washington, Saturday, November 3, 1945 The President War Department. Appointments to ' CONTENTS clerical positions on the Isthmus of Pan ama paying $120 in United States cur THE PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE ORDER 9653 rency per month or less may be made without examination. Executive Order: Page Amending Schedules A and B of the Civil Service Rules, amendments Civil Service R ules Paragraph 3, Subdivision VII of Sched - of Schedules A and B____ 13619 ule A is amended to read: By virtue of the authority vested in REGULATIONS AND NOTICES me by Section 2 of the Civil Service Act 3. Clerks in fourth class post offices. (22 Stat. 403), Schedules A ahd B of the Paragraph 7, Subdivision VII of Sched Civil Service Commission: Civil Service Rules are hereby amended ule A is amended to read: Schedule A: Nonclassifled posi as follows: tions excepted from exami 7. Special delivery messengers in sec nation under § 2.3 (b), cross Paragraph 6, Subdivision I of Sched ond, third, and fourth class post offices. ule A is amended to read: reference_______________ 13621 Paragraph 8, Subdivision VII of Sched Schedule B: Nonclassifled posi 6. Any person receiving from one deule A is amended to read: tions which may be filled partment or establishment of the Gov upon noncompetitive exam ernment for his personal salary com 8. Unskilled laborers employed as jani inations under § 2.3 (c), pensation aggregating not more than tors and cleaners in small postal units cross reference__________ 13621 $648 per annum whose duties require in leased quarters at a compensation less Commerce Department: only a portion of his time, or whose than $1299 per annum. -

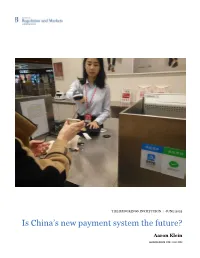

Is China's New Payment System the Future?

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION | JUNE 2019 Is China’s new payment system the future? Aaron Klein BROOKINGS INSTITUTION ECONOMIC STUDIES AT BROOKINGS Contents About the Author ......................................................................................................................3 Statement of Independence .....................................................................................................3 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 5 Understanding the Chinese System: Starting Points ............................................................ 6 Figure 1: QR Codes as means of payment in China ................................................. 7 China’s Transformation .......................................................................................................... 8 How Alipay and WeChat Pay work ..................................................................................... 9 Figure 2: QR codes being used as payment methods ............................................. 9 The parking garage metaphor ............................................................................................ 10 How to Fund a Chinese Digital Wallet .......................................................................... -

Silver Key Builder Drops Project Plan by Dawn Grodsky Armenia, a Captiva Resident, Did Editor Not Return Phone Calls

', I ' ' / JUNE 11, 1993 VOLUME 22 #* '£ /* * •' NUMBER 24 3 SECTIONS, 44 PAGES iv!1 ' REP SANIBEL AND CAPTIVA, FLORIDA Silver Key builder drops project plan By Dawn Grodsky Armenia, a Captiva resident, did Editor not return phone calls. His attor- John Armenia, the developer who ney. Tallahassee-based Kenneth G. has been seeking permits to build Oertel. who signed the withdrawal three, single-family homes on notice with the DER, was out of the Silver Key for more than two years, country and unavailable for com- withdrew a key permit application ment. from the Florida Department of It: is unclear why Armenia would Environmental Regulation (DER) want to withdraw the permit appli- last week. cation he fought so hard to get, Armenia also withdrew a subdivi- especially when the DER had stated sion permit application with the its intention to issue it. City of Sanibel, according to the When the DER first stated its city's planning department. intent in 1991, a series of legal Silver Key is a small, undevel- cases resulted. oped island located between Clam The City of Sanibel, a consortium Bayou and Blind Pass, behind of 12 Clam Bayou-area residents, Bowman's Beach. the Sanibel/Captiva Conservation The DER dredge and fill permit Foundation, the Committee of application, withdrawn Wednesday, Neighborhood Associations (CONA) June 2, would have allowed and Committee of the Islands Armenia to build an access bridge (COTI) challenged the DER's intent. from Sanibel-Captiva Road and The plaintiffs claimed that Clam across Clam Bayou to the key, Bayou was part of the Pine Island paving the way for the development of the homes. -

Wonderstruck

WONDERSTRUCK Screenplay by Brian Selznick Based on the book by Brian Selznick © 201(6) AMAZON.COM, INC. OR ITS AFFILIATES. All Rights Reserved. This material is the exclusive property of AMAZON.COM, INC. OR ITS AFFILIATES and is intended solely for the use of its personnel. No portion of this script may be performed, or reproduced by any means, or quoted, or published in any medium without prior written consent of AMAZON.COM, INC. OR ITS AFFILIATES. BLACKNESS Rising up WE HEAR: The sound of a boy’s panting while he runs. His footsteps crunching. Faster and faster, louder and louder. SUDDENLY - 1 EXT. SNOWY MINNESOTA WOODS - 1977 - NIGHT 1 The roar of some terrifying creature. We are close to the BOY, age twelve, racing through the snowy dark. He is terrified. He manages to glance back behind him. In a shaky dark swirl we catch glimpses of what appear to be animals, black against the blue snow, chasing after him. In a glimpse of light their eyes flash, revealing TWO WOLVES - tearing through the moonlit woods. The boy tries desperately to pick up speed, dodging fallen limbs and rocks along his way. Strangely, he’s barefoot, in a thin tank-top and pajama bottoms, running through a dark, eerie landscape. Up ahead he sees a way to veer off from the path and dip down along an incline. He takes the turn, tearing through brush as he descends along the side of a hill into a slight recess, hoping to drop out of sight. Through the black mesh of trees he spots the wolves running past. -

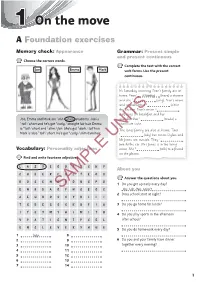

Sample Units

On the move A Foundation exercises Memory check: Appearance Grammar: Present simple and present continuous 1 Choose the correct words. 3 Complete the text with the correct Joe Emma Mark verb forms. Use the present continuous. It’s Saturday morning. Fran’s family are at home. Fran 1 is having (have) a shower and she 2 (sing). Fran’s mum and grandmother 3 (sit) in the kitchen. Fran’s mum 4 (eat) eggs for breakfast and her Joe, Emma and Mark are 1 old / young students. Joe is grandmother 5 (make) a 2 tall / short and he’s got 3 curly / straight fair hair. Emma chocolate cake. is 4 tall / short and 5 slim / fair. She’s got 6 dark / tall hair. 7 8 The Jones family are also at home. Tara Mark is also tall / short . He’s got curly / slim dark hair. 6 (tidy) her room. Dylan and UNITSMr Jones are outside. They 7 (wash) the car. Mrs Jones is in the living Vocabulary: Personality adjectives room. She 8 (talk) to a friend on the phone. 2 Find and write fourteen adjectives. L A Z Y E O O P T S H Y About you C H E E R F U L T E O S 4 Answer the questions about you. R O G E N E R O U S P O 1 Do you get up early every day? E N R D A O SAMPLE P N G E O C Yes, I do./No, I don't. 2 Does school start at eight? A E U B O S S Y R L L I T S D E G S S K U F I A 3 Do you go home for lunch? I T E Y M Y H I M I T B 4 Do you play sports in the afternoon V P A T I E N T P S E L after school? E N C L E V E R Y H U E 5 Do you do homework every day? 1 lazy 8 2 9 6 Do you and your family have dinner 3 10 together every evening? 4 11 5 12 6 13 7 14 1 M01_TODA_ACB_03GLB_1150_U01.indd 1 28/02/2014 13:30 A Activation exercises Memory check: Appearance 1 Complete the description. -

Centralia Students Donate Hair to Create Wig for Girl with Leukemia

Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com $1 Napavine Early Week Edition Falls in Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017 Thriller / Sports 1 Pickpocketing in Morton ARTrails Set for SWW Spokane Man Jailed for Warrants and Lifting Dozens of Local Artists Prepare to Show Wallet Off of Elderly Morton Man / Main 6 Their Work in Annual Showcase / Life 1 WDFW Centralia Students Donate Hair to Timeline of Accused Create Wig for Girl With Leukemia Illegal Hunting DOCUMENTS: Tracing the Actions of Accused Poachers Across Southwest Washington and Oregon By Jordan Nailon [email protected] Editor’s Note: The following timeline is the latest in a series of articles detailing a massive poaching operation uncovered in Southwest Washington and Northwest Oregon. It comes af- ter a records request that yielded hundreds of pages of evidence collected by the Washington De- partment of Fish and Wildlife. See previous coverage at www. chronline.com Date: Aug. 29, 2015 Location: Gifford Pinchot National Forest south of Randle Suspects: Bryan Tretiak, Erik Martin, William Haynes, Jared Wenzelburger / [email protected] Joe Dills, and Eddy Dills Lily Hubbard, left, smiles as her friend, Ellen Buzzard, right, has her first lock of hair cut Saturday afternoon in downtown Centralia. The hair is being donated for the Bears hunted with the use of creation of Lily’s new wig. dogs. Video evidence appears to show Tretiak shooting a GIVING TO A FRIEND: Ellen black bear out of a tree. “That’s your typical National Forest Buzzard and Kaylee bear,” Joe Dills says on video. Rooklidge Cut Their Hair The bear was taken home by Tretiak. -

ED311449.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 449 CS 212 093 AUTHOR Baron, Dennis TITLE Declining Grammar--and Other Essays on the English Vocabulary. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1073-8 PUB DATE 89 NOTE :)31p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 10738-3020; $9.95 member, $12.95 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *English; Gr&mmar; Higher Education; *Language Attitudes; *Language Usage; *Lexicology; Linguistics; *Semantics; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Words ABSTRACT This book contains 25 essays about English words, and how they are defined, valued, and discussed. The book is divided into four sections. The first section, "Language Lore," examines some of the myths and misconceptions that affect attitudes toward language--and towards English in particular. The second section, "Language Usage," examines some specific questions of meaning and usage. Section 3, "Language Trends," examines some controversial r trends in English vocabulary, and some developments too new to have received comment before. The fourth section, "Language Politics," treats several aspects of linguistic politics, from special attempts to deal with the ethnic, religious, or sex-specific elements of vocabulary to the broader issues of language both as a reflection of the public consciousness and the U.S. Constitution and as a refuge for the most private forms of expression. (MS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY J. Maxwell TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." U S. -

The Current and Future State of Digital Wallets

The Current and Future State of Digital Wallets A guide to help understand where the Digital Wallet market is and where it is heading. For business and personal use. v1.0 2019-04-28 Author: Darrell O’Donnell, P.Eng. President & CEO Continuum Loop Inc. Released under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License The Current and Future State of Digital Wallets TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 6 2. Introduction 8 2.1. Structure of the Report 9 2.2. Report/Project Approach 10 3. What Is A Digital Wallet? 12 3.1. Let’s Clear up Some Terms 13 3.2. What Aren’t We Covering 14 3.2.1. Payments 14 3.2.2. Personal Data Stores 14 3.2.3. Crypto Wallets 15 3.2.4. Hardware Wallets 15 3.2.5. The Long History of Digital Wallets 15 3.3. What Can’t a Wallet Do? 16 3.4. What is an Agent? 16 3.5. The Most Basic Digital Wallet 16 3.6. How Do You Use A Digital Wallet? 17 4. Digital Wallet - Deeper Detail 19 4.1. You Already Have a Digital Wallet 19 4.2. What Is At Risk 20 4.3. Detailed Capabilities of Wallets & Agents 20 4.3.1. Credentials – Receiving, Offering, and Presenting 20 4.3.2. Authenticating – Logging You In 21 4.3.3. Organizing 21 4.3.4. Rendering 22 4.3.5. Personas 22 4.3.6. Private Connections 22 4.3.7. Emergency Access 23 4.3.8. Trust Hubs/Registries 24 4.3.9. -

RTD Construction Safety Guideline

Construction Safety Guidelines Statement of Safety Policy It is the policy of the Regional Transportation District to maintain a safe working environment for all District employees, contractor employees and the public. The active support of and participation in the safety program by all RTD personnel, consultants, contractors, subcontractors and work force is mandatory. The RTD FasTracks Construction Safety Guidelines is one of RTD’s construction documents and noncompliance with safety specifications will be treated the same as noncompliance with any contract item. The RTD FasTracks Construction Safety Guidelines does not take the place of the applicable OSHA, Federal, Sate, or Local safety regulations. The contractors and subcontractors are responsible for compliance with all applicable regulations. Workers on all projects are expected to maintain safe work practices, observe known and posted safety rules, and conduct themselves in a manner which will not place themselves, fellow employees or the public in danger. A job must never become so routine or urgent that safety precautions are ignored. The prevention of accidents, injury and damage to property hold equal priority to efficient production. Therefore, safety must remain a priority in the minds of every employee. V.1 5/19/2008 i Construction Safety Guidelines Table of Contents 1.0 Scope And Application ..................................................................................................1 2.0 Project Safety Goals and Objectives ............................................................................3 -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI' Bell & Howell Information and teaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 A GENERIC ANALYSIS OF THE RHETORIC OF HUMOROUS INCIVILITY IN POPULAR CULTURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial FuljBUment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Laura K. -

Peabody Mourns Death of School Superintendent Square One Sees

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2019 Artist brews up Peabody a picturesque mourns death autumn setting of school By Steve Krause ITEM STAFF LYNN — The assignment was to draw superintendent a label for a beer can that evoked imag- es of a harvest. By Thor Jourgensen The name of the beer brewed by Bent ITEM STAFF Water in Lynn is “Harvester American PEABODY — City residents celebrating Brown Ale,” after all, and it was Michael the start of the holiday season were stunned Aghahowa got the gig to come up with to receive news from Mayor Edward Betten- the label. The Lynn native and Lynn court Friday about the death of School Su- Tech graduate began thinking about perintendent Cara Murtagh. what the word “harvest” meant to him. “I am very sorry to share with you the “I thought of what the word ‘harvester’ terrible news of the sudden and unexpect- meant,” said the 25-year-old Aghahowa. ed passing of School Superintendent Cara “It’s the collection of crops. It makes me Murtagh,” Bettencourt said in a robo call think of crops, of living off the land, of and in a statement posted on Facebook. appreciating nature at its finest.” “Superintendent Murtagh’s talent, energy And that certainly fits Aghahowa’s and can-do spirit inspired all those whose nature, so to speak. lives she touched. Her selfless devotion to “I go walking through Lynn Woods a our students, faculty and staff, combined lot with my friend and her dog during with her lifelong passion for education, lift- the height of fall, and we’ve really come ed the entire Pea- to appreciate the beauty of nature, see- body school com- ing all the different colors of the leaves.” munity.