5028421954882.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natura Artificiale Di Vivaldi

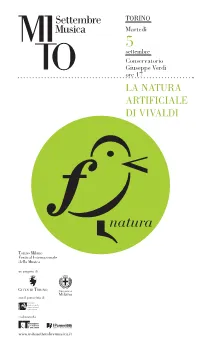

TORINO Martedì 5 settembre Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi ore 17 LA NATURA ARTIFICIALE DI VIVALDI natura www.mitosettembremusica.it LA NATURA ARTIFICIALE DI VIVALDI Nei primissimi anni del Settecento, intrisi di razionalismo, si parla in continuazione di «Natura» come modello, e la naturalezza è il fine d’ogni arte. Quello che crea Vivaldi, molto baroccamente, è una finta natura: l’estremo artificio formale mascherato da gesto normale, spontaneo. E tutti ci crederanno. Il concerto è preceduto da una breve introduzione di Stefano Catucci Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto in la minore per due violini e archi da L’Estro Armonico op. 3 n. 8 RV 522a Allegro – [Adagio] – [Allegro] Sonata in sol maggiore per violino, violoncello e basso continuo RV 820 Allegro – Adagio – Allegro Concerto in re minore per violino, archi e basso continuo RV 813 (ms. Wien, E.M.) Allegro – [Adagio] – Allegro – Adagio – Andante – Largo – Allegro Concerto in sol maggiore per flauto traversiere, archi e basso continuo RV 438 Allegro – Larghetto – Allegro Sonata in re minore per due violini e basso continuo “La follia” op. 1 n. 12 RV 63 Tema (Adagio). Variazioni Giovanni Stefano Carbonelli (1694-1772) Sonata op. 1 n. 2 in re minore Adagio – Allegro Allegro Andante Aria Antonio Vivaldi Concerto in mi minore per violino, archi e basso continuo da La Stravaganza op. 4 n. 2 RV 279 Allegro – Largo – Allegro Modo Antiquo Federico Guglielmo violino principale Raffaele Tiseo, Paolo Cantamessa, Stefano Bruni violini Pasquale Lepore viola Bettina Hoffmann violoncello Federico Bagnasco contrabbasso Andrea Coen clavicembalo Federico Maria Sardelli direttore e flauto traversiere /1 Vivaldi natura renovatur. -

Chorale Prélude "Gelobet Seist Du, Jesu Christ"

Simone Stella Arranger, Composer, Interpreter, Publisher, Teacher Italia, Firenze About the artist Born in Florence (Italy) in 1981, Simone Stella studied piano at the Conservatory ?L. Cherubini? of Florence with Rosanita Racugno, and perfected his piano studies with Marco Vavolo. After studying organ in Florence with Mariella Mochi and Alessandro Albenga, harpsichord in Rome with Francesco Cera, and organ improvisation in Cremona with Fausto Caporali and Stefano Rattini, he has attended many courses and seminars held by internationally acclaimed artists, including Ton Koopman, Matteo Imbruno, Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini, Luca Scandali, Giancarlo Parodi, Stefano Innocenti, Klemens Schnorr, Ludger Lohmann, Michel Bouvard, Monika Henking, Guy Bovet. He won the 2nd and 3rd ?A. Esposito? Youth Organ Competition held in Lucca (2004-05) and then the 1st ?Agati-Tronci? International Organ Competition held in Pistoia (2008). Simone Stella plays, especially as a soloist, in Italy, Spain, Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark. His repertoire includes harpsichord and organ music from every historical era up to and including the present day. Particularly interesting is his live performance (2009-10) of the complete organ works by Dieterich Buxtehude in the historical Orsanmichele Church in Florence, where he was titular organist. He is an active composer of inst... (more online) Personal web: http://www.simonestella.it About the piece Title: Chorale Prelude "Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ" Composer: Stella, Simone Licence: Creative Commons Attribution-Non -

Dietrich Buxtehude Préludes, Chorals, Passacaille… Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dietrich Buxtehude Préludes, Chorals, Passacaille… mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Préludes, Chorals, Passacaille… Country: France Released: 1984 Style: Baroque MP3 version RAR size: 1233 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1154 mb WMA version RAR size: 1176 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 291 Other Formats: FLAC XM MOD MMF WMA MP2 ASF Tracklist A1 Praeludium En Ut Majeur, BuxWV 137 5:02 A2 Choral, BuxWV 197 2:23 A3 Choral, BuxWV 223 5:58 A4 Choral, BuxWV 3:30 A5 Tocata En Ré Mineur, BuxWV 155 6:44 B1 Praeludium En Sol Mineur, BuxWV 149 6:36 B2 Choral, BuxWV 199 3:31 B3 Passacaglia En Ré Mineur, BuxWV 161 5:19 B4 Choral, BuxWV 190 2:40 B5 Choral, BuxWV 183 3:23 B6 Praeludium En Ré Majoeur, BuxWV 139 5:13 Credits Composed By – Dieterich Buxtehude Edited By – Ysabelle Van Wersch-Cot Liner Notes [English Translation] – Nicholas Powell Liner Notes [German Translation] – Ingrid Trautmann Organ [Haerpfer-erman , Sainte Chapelle, Châteu Des Ducs De Savoie, Chambéry], Liner Notes – Marie-Claire Alain Photography – Studio Mollard Recording Supervisor, Engineer [Sound] – Yolanta Skura Notes The distributor's Catalog# is printed on a sticker pasted over the label's Catalog# on the back cover. The backcover's tracklist featured subtitles to the following tracks: A1 > (Prélude, fugue, Chaconne) A2 > "In dulci jubilo" A3 > "Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern" A4 > "Ach Herr, mich armen Sünder" B2 > "Komm, Heiliger Geist, Herre Gott" B4 > "Gott der Vater wohn uns bei" B5 > "Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt" Barcode and Other Identifiers -

Federico Maria Sardelli

F EDERICO M ARIA S A R D E L L I – Conductor In 1984 Federico Maria Sardelli, originally a flutist, founded the Baroque orchestra Modo Antiquo, with which he appears, as both soloist and conductor, at major festivals throughout Europe and in such concert halls as Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées Paris, Tchaikovsky Concert Hall Moscow and Auditorium Parco della Musica in Rome. He is regularly invited as a guest conductor by many prestigious symphony orchestras, including Orchestra Barocca dell’Accademia di Santa Cecilia di Roma, Gewandhaus Lipzig, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Filarmonica Arturo Toscanini, Orchestra Filarmonica di Torino, Staatskapelle Halle, Kammerakademie Potsdam, Real Filarmonia de Galicia, Orchestra dei Pomeriggi Musicali di Milano. Federico Maria Sardelli has been a notable protagonist in the Vivaldi renaissance of the past few years: he conducted the world premiere recording and performance of many Vivaldi’s operas. In 2005, at Rotterdam Concertgebouw, he conducted the world premiere of Motezuma , rediscovered after 270 years. In 2006 he conducted the world premiere of Vivaldi’s L’Atenaide at Teatro della Pergola in Florence. In 2012 he recorded the last eight Vivaldi works reappeared ( New Discoveries II , Naïve) and conducted the world premiere of the new version of Orlando Furioso , rediscovered and reconstituted by him (Festival de Beaune, Naïve recording). In 2007 he has been Principal Conductor of Händel Festspiele in Halle, where he conducted Ariodante. Among the most important production he has conducted, Giasone by Francesco Cavalli at Vlaamse Opera Antwerp, Olivo e Pasquale at Festival Donizetti Bergamo, Dido and Aeneas at Teatro Regio Turin, La Dafne and Alceste at Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Händel’s Teseo at Tchaikovsky Concert Hall in Moscow. -

5) Musikstunde

__________________________________________________________________________ 2 SWR 2 Musikstunde Freitag, den 13. Januar 2012 Mit Susanne Herzog Il prete rosso Vivaldi – unsterblich? Turin: was hat Vivaldis Musik – vielmehr seine Manuskripte – was haben die in Turin zu suchen? In dicke Bände gebunden, mit den Vignetten zweier Kleinkinder versehen? Zurück an den Anfang der Geschichte: 1926 saß der Musikhistoriker Alberto Gentili vor fünfundneunzig dicken Bänden mit Musik. Mönche des Salesianerkloster S. Carlo hatten ihn gebeten, den Wert dieser Manuskripte zu schätzen. Denn ihr Kloster, das musste dringend in Stand gesetzt werden. So dringend, dass man sich entschloss, Teile der Bibliothek zu verkaufen. Gentili also blätterte in den Bänden der Klosterbrüder und stellte bereits nach kurzer Zeit fest: das war eine echte Sensation, die er da in den Händen hielt: vierzehn dieser fünfundneunzig Bände enthielten Musik von Antonio Vivaldi. Ein Zufallsfund, der Vivaldi zu der Unsterblichkeit verholfen hat, die er heute in unserem Musikleben genießt. Und damit herzlich willkommen zur heutigen SWR 2 Musikstunde. 0’56 Musik 1 Antonio Vivaldi Zweiter Satz aus Konzert C-Dur RV 556 <18> Largo 3’00 Ensemble Matheus Jean-Christophe Spinosi, Ltg. Titel CD: Vivaldi. Concerti con Molti Strumenti Disques Pierre Verany, PV 796023, kein LC WDR 5021 145 2 3 Klingt so gar nicht nach Vivaldi: war aber Vivaldi: ein langsamer Satz, der ganz im Zeichen des dunklen Timbres der Klarinette steht. Jean- Christophe Spinosi musizierte mit seinem Ensemble Matheus. 140 Instrumentalwerke, 29 Kantaten, zwölf Opern, ein Oratorium und einige Fragmente, meist autograph von Vivaldi: Gentili war sofort klar: was er da gefunden hatte, das sollte die Turiner Nationalbibliothek erwerben: Aber eine Frage blieb doch noch: wie waren diese Autographe überhaupt in das Kloster gelangt? Und damit noch einen Schritt zurück in der Geschichte: als Vivaldi 1741 in Wien starb, hatte er auf seiner Reise nicht seine umfangreiche Bibliothek mitgeführt. -

Replacement of the Recorder by the Transverse Flute During the Baroque and Classical Periods Victoria Boerner Western University, [email protected]

Western University Scholarship@Western 2018 Undergraduate Awards The ndeU rgraduate Awards 2018 Replacement of the Recorder by the Transverse Flute During the Baroque and Classical Periods Victoria Boerner Western University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/undergradawards_2018 Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boerner, Victoria, "Replacement of the Recorder by the Transverse Flute During the Baroque and Classical Periods" (2018). 2018 Undergraduate Awards. 10. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/undergradawards_2018/10 REPLACEMENT OF THE RECORDER BY THE TRANSVERSE FLUTE DURING THE BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL PERIODS Victoria Boerner Music 2710 F Submitted to Dr. K. Helsen December 2, 2014 Boerner 1 Abstract: While the recorder today is primarily an instrument performed by school children, this family of instruments has a long history, and was once more popular than the flute. This paper examines when, why, and how the Western transverse flute surpassed the recorder in popularity. After an explanation of the origins, history, and overlapping names for these various aerophones, this paper examines the social and cultural, technical, and musical reasons that contributed to the recorder’s decline. While all of these factors undoubtedly contributed to this transition, ultimately it appears that cultural, economic, and technical reasons were more important than musical ones, and eventually culminated in the greatly developed popular contemporary flute, and the unfortunately under respected recorder. Boerner 2 The flute family is one of the oldest instrumental families, originating in the late Neolithic period. There are several forms of flutes classified by their method of sound production; for Western music from 1600 to 1800, the most important are the end-blown recorder and cross blown flute. -

Venice Baroque Orchestra: Vivaldi's Juditha Triumphans

PHOTO BY MATTEODA FINA VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA: VIVALDI’S JUDITHA TRIUMPHANS Saturday, February 4, 2017, at 7:30pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA 300TH ANNIVERSARY TOUR OF VIVALDI’S ORATORIO JUDITHA TRIUMPHANS Andrea Marcon, music director and conductor Delphine Galou, Juditha Mary-Ellen Nesi, Holofernes Ann Hallenberg, Vagaus Francesca Ascioti, Ozias Silke Gäng, Abra Women of the University of Illinois Chamber Singers Andrew Megill, director Antonio Vivaldi Juditha triumphans, RV 644 (1716) (1678-1741) Devicta Holofernis barbarie Sacrum militare oratorium Oratorio in two parts, presented with one 20-minute intermission. Juditha triumphans, commissioned by the Republic of Venice to celebrate the naval victory over the Ottoman Empire at Corfu in 1716, portrays the dramatic story of the Hebrew woman Judith overcoming the invading Assyrian general Holofernes and his army. The Venice Baroque Orchestra is suported by the Fondazione Cassamarca in Treviso, Italy. The Venice Baroque Orchestra appears by arrangement with: Alliance Artist Management 5030 Broadway, Suite 812 New York, NY 10034 www.allianceartistmanagement.com 2 THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE THANK YOU TO THE SPONSORS OF THIS PERFORMANCE Krannert Center honors the spirited generosity of these committed sponsors whose support of this performance continues to strengthen the impact of the arts in our community. * JOAN & PETER HOOD Sixteen Previous Sponsorships Two Current Sponsorships * PAT & ALLAN TUCHMAN Five Previous Sponsorships Two Current Sponsorships *PHOTO CREDIT: ILLINI STUDIO 3 * * JAMES ECONOMY ALICE & JOHN PFEFFER Special Support of Classical Music Nineteen Previous Sponsorships One Season Sponsorship * * THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE MARLYN RINEHART JUDITH & RICHARD SHERRY & NELSON BECK Nine Previous Sponsorships KAPLAN First-Time Sponsors First-Time Sponsors * * CAROLYN G. -

Antonio Vivaldi «The Four Seasons» Nature and the Culture of Sound

Antonio Vivaldi «The Four Seasons» The Contest Between Harmony and Invention First violins: Federico Cardilli*, Azusa Onishi, Eleonora Minerva, Sabina Morelli Second violins: Leonardo Spinedi*, Francesco Peverini, Alessandro Marini, Vanessa Di Cintio Violas: Gianluca Saggini*, Riccardo Savinelli, Luana De Rubeis Cellos: Giulio Ferretti*, Chiara Burattini Double bass: Alessandro Schillaci Harpsichord: Ettore Maria del Romano Nature and the culture of sound The concerts that we’ve become accustomed to call The Four Seasons, are contained in a series of twelve and were published in Amsterdam in 1725 as Opera 8. Vivaldi himself entitled the work, Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione (The Pursuit of Harmony and Invention). The collection is dedicated to the Bohemian Count Wenzel von Morzin, who requested the composer as his “maestro of music in Italy”, that is, as a non-resident Kappellmeister: Vivaldi’s fame was widespread in all of Europe. There is no need to add a single word of comment to the title: cimento (pursuit, or test) / armonia (harmony) / invenzione (invention), the sense of composition, between rules and freedom, science and art, is perfectly contained there in. The Seasons – the first four concert of the collection, in the sequence of Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter – are each accompanied by a sonnet by an anonymous poet. There is reason to believe that the author is Vivaldi himself. The sonnets were neglected on the basis of their literary quality (in a critical review of the work from 1950, Gian Francesco Malipiero misjudges them, “captions of an extremely Baroque nature that define the character of the work as almost that of program music”). -

22 Modo Antiquo SPIRITO DI CORELLI.Pdf

spiriti Sabato Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi ore 20 - ore 22.30 TORINO 12 LO SPIRITO settembre DI CORELLI Torino Milano Festival Internazionale della Musica Un progetto di Con il contributo di Realizzato da LO SPIRITO DI CORELLI Corelli fu il modello di perfezione riconosciuto sino alla fine del Settecento. I suoi pochi lavori furono pubblicati e ripubblicati, copiati e diffusi in tutta Europa. Così il suo spirito animò Händel e Geminiani, suoi allievi, e il giovane Vivaldi, e ancora forse aleggia, in un brano scritto apposta per questo concerto. Il concerto è preceduto da una breve introduzione di Stefano Catucci. Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) Concerto grosso n. 4 in re maggiore op. 6 Adagio. Allegro – Adagio – Vivace – Allegro Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762) Concerto grosso n. 2 in sol minore op. 3 Largo e staccato – Allegro – Adagio – Allegro Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759) Concerto grosso n. 4 in fa maggiore op. 3 HWV 315 Andante. Allegro. Lentement – Andante – Allegro – Minuetto alternativo Federico Maria Sardelli (1963) Concerto grosso nello spirito di Corelli PRIMA ESECUZIONE ASSOLUTA Georg Friedrich Händel Concerto grosso n. 6 in sol minore op. 6 HWV 324 Largo e affettuoso – A tempo giusto – Musette. Larghetto – Allegro Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto n. 11 in re minore RV 565 da L’Estro Armonico op. 3 Allegro – Adagio e spiccato – Allegro – Largo e spiccato – Allegro Modo Antiquo Federico Maria Sardelli direttore La direzione artistica del festival invita a non utilizzare in alcun modo gli smartphone durante il concerto, nemmeno se posti in modalità aerea o silenziosa. L’accensione del display può infatti disturbare gli altri ascoltatori. -

Buxtehude Complete Harpsichord Music Mp3, Flac, Wma

Buxtehude Complete Harpsichord Music mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Complete Harpsichord Music Country: Netherlands Released: 2012 Style: Baroque MP3 version RAR size: 1626 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1394 mb WMA version RAR size: 1349 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 916 Other Formats: MP3 ASF ADX MP2 MP4 WMA AU Tracklist Volume 1 Aria 'Rofilis' In D Minor BuxWV248 1-1 Variatio 1 - Variatio 3 2:12 Suite In G BuxWV240 1-2 I. Allemande 2:27 1-3 II. Courante 2:07 1-4 III. Sarabande 1:43 1-5 IV. Gigue 1:02 Suite In E Minor BuxWV237 1-6 I. Allemande 3:01 1-7 II. Courante 1:36 1-8 III. Sarabande I 2:48 1-9 IV. Sarabande II 1:50 1-10 V. Gigue 1:38 - 1-11 Courante In D Minor BuxWV Anh.6 1:41 Suite In D Minor BuxWV234 1-12 I. Allemande 2:40 1-13 II. Double 2:26 1-14 III. Courante 2:52 1-15 IV. Double 1:31 1-16 V. Sarabande I 2:25 1-17 VI. Sarabande II 1:54 Suite In D BuxWV232 1-18 I. Allemande 2:16 1-19 II. Courante 1:44 Auf Meinen Lieben Gott In E Minor BuxWV179 1-20 I. Allemande 0:55 1-21 II. Double 0:57 1-22 III. Corrente 0:42 1-23 IV. Sarabande 1:25 1-24 V. Gigue 0:45 Suite In C BuxWV230 1-25 I. Allemande 2:21 1-26 II. Courante 1:52 1-27 III. -

Froberger's Fantasias and Ricercars Four Centuries On1 Terence

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Royal College of Music Research Online Journal of the Royal College of Organists , Volume 10 (December 2016), pp. 5–27. Searching fantasy: Froberger’s fantasias and ricercars four centuries on1 Terence Charlston ‘Obscure, profound it was, and nebulous’ 2 It is more than a little surprising, given Johann Jacob Froberger’s significance in the written history of music, how little of his music is regularly played or known today. Traditionally he is viewed as the most important German seventeenth-century keyboard composer, pre-eminent alongside Frescobaldi and Sweelinck, the ‘Father’ of the Baroque keyboard suite. He was celebrated in his own day and his reputation and works were considered important enough to be researched and preserved by following generations. Today the physical notes of his music are readily available in facsimile and modern ‘complete’ editions (see Table 1) and the identification of several new sources of his music since the 1960s, one of which is an autograph with 13 otherwise unknown pieces, have generated renewed interest and discussion.3 Nonetheless, Froberger’s music is still represented in concert and recording only by the same handful of more ‘popular’ pieces which have graced recital programmes and teaching curricula for at least the last 70 years. These few pieces, chosen for their exceptional rather than their representative qualities, leave the majority of his music in peripheral limbo. The exclusion of the less Terence Charlston, ‘Searching fantasy: Froberger’s fantasias and ricercars four centuries on’ © Terence Charlston, 2016. -

Vivaldi Complete MP3 DVD-Details

Antonio Vivaldi (1678 – 1741) Sämtliche Werke / Complete works MP3 – Format Details Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Sämtliche Werke / Complete works MP3 - Die ID3-Tags enthalten alle Interpreten / The ID3-Tags contains the performers - Bezeichnugen der Tonarten / Descriptions of Keys: 1. Dur-Tonarten sind dargestellt in Großbuchstaben, Moll-Tonarten in Kleinbuchstaben Major-keys are described with capital letters, minor-keys with lower case letters 2. Die Bezeichnungen sind in englisch mit folgenden Ausnahmen / The Descriptions are in english with exceptions : B/b=deutsch H-Dur/moll , Bb/bb=deutsch B-Dur/moll, Ab/Eb,…=deutsch As/Es,... Ab,Eb,Bb,… = A,E,B flat Major/minor, Fis,Gis,… = F,G sharp Major/minor - b.c. = basso continuo (Generalbass / General basso) Gesamtzeit / Time sum 199:05:21 = 8 Tage 4 Stunden / 8 days 4 hours Titel / Title Zeit/Time Titel / Title Zeit/Time 1. Concertos 90:17:38 1.1. Concertos for Violin solo 38:59:40 op. 3 Orchestra da camera "I Filarmonici",Violin-Alberto Martini,Ettore Pellegrino,Stefano Pagliani 1.RV549 Conc.f.4 Violins,Cello,Strings & b.c. in D 0:08:14 7. RV567 Concerto for 4 Violins,Cello & b.c. in F 0:08:20 2.RV578 Concerto 2 for 2 Violins,Cello & b.c. in g 0:09:23 8. RV522 Concerto for 2 Violins & b.c. in a 0:10:32 3.RV310 Concerto for Violin,Strings & b.c. in G 0:06:34 9. RV230 Concerto for Violin & b.c. in D 0:07:43 4.RV550 Concerto for 4 Violins,Strings & b.c. in e 0:06:43 10.RV580 Concerto for 4 Violins,Cello & b.c.