Our Bodies Aren't Wonderlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

The Showgirl Goes On

Star_Jan02_p1-20_Layout 1 1/2/2013 3:31 PM Page 1 ONLINE GET SELECT CONTENT ON THE GO, WWW.MONTROSE-STAR.COM IS MOBILE ENABLED! The WWW.MONTROSE-STAR.COM YOUR GUIDE TO GLBT ENTERTAINMENT, RECREATION & CULTURE IN CENTRAL AND COASTAL TEXAS WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 2, 2013 H VOL. III, ISSUE 20 FEATURE n19 One Good Love CALENDAR n6 Next2Weeks! DINING GUIDE n14 Roots Juice Drink Your Veggies! COMMUNITY n6 HAPPY NEW YEAR! The Showgirl INDEX Editorial........................4 Non-Profits Calendar .....16 Goes On Cartoons ....................33 Crossword ..................33 p10 Lifestyles ....................31 Star_Jan02_p1-20_Layout 1 1/2/2013 2:58 PM Page 2 Page 2 Montrose Star H Wednesday, January 2, 2013 www.Montrose-Star.com H also find us onn F Facebook.com/Star.Montrose Star_Jan02_p1-20_Layout 1 1/2/2013 2:58 PM Page 3 Montrose Star H Wednesday, January 2, 2013 Page 3 www.Montrose-Star.com H also find us onn F Facebook.com/Star.Montrose Star_Jan02_p1-20_Layout 1 1/2/2013 2:58 PM Page 4 Page 4 Montrose Star H Wednesday, January 2, 2013 Op-ED CONTACT US: 713-942-0084 EMAIL: [email protected] publisher Executive Editor Health & Fitness Music Laura M. Villagrán Kenton Alan DJ Chris Allen Sales Director Davey Wavey DJ JD Arnold Angela K. Snell Dr. Randy Mitchmore DJ Mark DeLange Creep of the Week: production News & Features DJ Wild & DJ Jeff Rafael Espinosa Johnny Trlica Scene Writers Circulation & Distribution Jim Ayers Arts Reviews Miriam Orihuela Pope Benedic XVI Daddy Bob Bill O’Rourke & Loyal K Elizabeth Membrillo Stephen Hill Lifestyles Rey Lopez Gayl Newton By d’anne WitkoWski lent to a suicide bomber. -

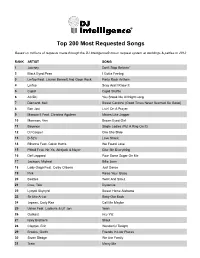

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

Uptownlive.Song List Copy.Pages

Uptown Live Sample - Song List Top 40/ Pop 24k Gold - Bruno Mars Adventure of A Lifetime - Coldplay Aint My Fault - Zara Larsson All of Me (John Legend) Another You - Armin Van Buren Bad Romance -Lady Gaga Better Together -Jack Johnson Blame - Calvin Harris Blurred Lines -Robin Thicke Body Moves - DNCE Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Cake By The Ocean - DNCE California Girls - Katy Perry Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepsen Can’t Feel My Face - The Weeknd Can’t Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Cheap Thrills - Sia Cheerleader - OMI Clarity - Zedd feat. Foxes Closer - Chainsmokers Closer – Ne-Yo Cold Water - Major Lazer feat. Beiber Crazy - Cee Lo Crazy In Love - Beyoncé Despacito - Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee and Beiber DJ Got Us Falling In Love Again - Usher Don’t Know Why - Norah Jones Don’t Let Me Down - Chainsmokers Don’t Wanna Know - Maroon 5 Don’t You Worry Child - Sweedish House Mafia Dynamite - Taio Cruz Edge of Glory - Lady Gaga ET - Katy Perry Everything - Michael Bublé Feel So Close - Calvin Harris Firework - Katy Perry Forget You - Cee Lo FUN- Pitbull/Chris Brown Get Lucky - Daft Punk Girlfriend – Justin Bieber Grow Old With You - Adam Sandler Happy – Pharrel Hey Soul Sister – Train Hideaway - Kiesza Home - Michael Bublé Hot In Here- Nelly Hot n Cold - Katy Perry How Deep Is Your Love - Calvin Harris I Feel It Coming - The Weeknd I Gotta Feelin’ - Black Eyed Peas I Kissed A Girl - Katy Perry I Knew You Were Trouble - Taylor Swift I Want You To Know - Zedd feat. Selena Gomez I’ll Be - Edwin McCain I’m Yours - Jason Mraz In The Name of Love - Martin Garrix Into You - Ariana Grande It Aint Me - Kygo and Selena Gomez Jealous - Nick Jonas Just Dance - Lady Gaga Kids - OneRepublic Last Friday Night - Katy Perry Lean On - Major Lazer feat. -

13-030113.Compressed.Pdf

King & Queen of the Rodeo BrlanBlck lJcIuolFlnt Schedule Of Events: Satu«iay Mlch 16,2013 !OOrsdri MatchlU13 8:30am· Mardattty NewContestant Meeq 2:00pm. fIllse Stdli(bec~~nbegi"6,Pasatna Fai~lOunds 9:ooam·H. Noolish (approUmatelyl· Grand Entry BAYOU BEAU 8:00pm. lone ~at lit ~v~,8's Aftemooo· Rodeoc.ontiwes ~gaCJ....•••9:00pm. ~amondsand Peansrnee~ DenimaM Spursatlre e,qs S:30pm •Happy Hour at TwoCities Bar and Grin CClfMNntt~ Health Services. Frilai MardiII, m13 7:00 pm· 0kIah00la Tea Party, EJ's "'_I ..u,•••" ••• 8:l0 am· Rodeo Sdilol Regi~lation SundaYMarch 17,lOll sabayc)ubeeu.com 9:00am· Rodeo Scoool and Safety Oass,PasaO!IIa Fai~roonds 9:30am·H. NooIish (approUmatelyl· Grand Entry 9:00am· HI.\'le1141(re~·in begms,PasadenaF~rgrcunds Aftemooo· Rodeoamtillles 6:00pmtil9:OO pm. ContestdntandVolJnteerRegistlilt~n, HllItHotel 7:00 pm· DiMer at the BRB Ii>. lO:OOpm·ffingIirue, HeI-n-Heek vsHell-n·Hoovesaltlf e,qs 8:00pm· Rodeo Awards at the BRB MONTROSEST.t ril ~ YELLOW V\:::IulOJHgt 10 nJU Hcu5"'Ol',GlBT Co' NO ".- ~ $1 cups -..~'tll the kegs run dry ~ MARCH 15&16 Sunday 3/10/13 @ 5:00 YOU JUST MIGHT GET 330 San Pedro, San Antonio, TX ~ ~b' AN~ "1 ufJ!lfJu Motivation By Jennifer Webb Perception My next series of articles deals with perception, us) we miss what's in front of our face. And we're because it can get in our way more than most of not alone. Everyone out there is doing the same us realize. And this week, let's look at how we can thing we are. -

Show Code: #12-50 Show Date: Weekend of December 8-9, 2012 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg

Show Code: #12-50 Show Date: Weekend of December 8-9, 2012 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg. 1 Content: #40 “REMEMBER WHEN (PUSH REWIND)” – Chris Wallace #39 “SOMEBODY THAT I USED TO KNOW” – Gotye #38 “OATH” – Cher Lloyd f/Becky G. Commercials: :30 Pier One :30 Barnes & Noble :30 Toys R Us :30 State Farm Auto Outcue: “...to a better state.” Segment Time: 14:02 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 2 Content: #37 “READY OR NOT” – Bridgit Mendler #36 “WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN” – Rihanna #35 “CATCH MY BREATH” – Kelly Clarkson #34 “ANYTHING COULD HAPPEN” – Ellie Goulding Commercials: :30 Subway/Fresh Buzz :30 Zazzle.com :30 Coca-Cola :30 Pier One Outcue: “...Pier One Imports.” Segment Time: 18:38 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 3 Content: #33 “TITANIUM” – David Guetta f/Sia Break Out: “BAD FOR ME” – Megan & Liz Extra: “SCREAM” – Usher #32 “DON'T STOP THE PARTY” – Pitbull f/TJR #31 “HALL OF FAME” – The Script f/will.i.am Commercials: :30 Telestrations :30 State Farm Auto Outcue: “...to a better state.” Segment Time: 19:20 Local Break 1:00 Seg. 4 ***This is an optional cut - Stations can opt to drop song for local inventory*** Content: AT40 Extra: “BOYFRIEND” – Justin Bieber Outcue: “…Seacrest on Twitter.” (sfx) Segment Time: 3:23 Hour 1 Total Time: 60:23 END OF DISC ONE Show Code: #12-50 Show Date: Weekend of December 8-9, 2012 Disc Two/Hour Two Opening Billboard None Seg. 1 Content: #30 “WIDE AWAKE” – Katy Perry #29 “LIVE WHILE WE'RE YOUNG” – One Direction #28 “50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE” – Train Commercials: :30 Subway/Fresh Buzz :30 Toys R Us :30 Atlantic/Wiz Khalifa :30 Zazzle.com Outcue: “...code holiday magic.” Segment Time: 13:44 Local Break 2:00 Seg. -

Why Hip-Hop Is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music

Why Hip-Hop is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez Advisor: Dr. Irene Mata Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies May 2013 © Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 “These Are the Breaks:” Flow, Layering, Rupture, and the History of Hip-Hop 6 Hip-Hop Identity Interventions and My Project 12 “When Hip-Hop Lost Its Way, He Added a Fifth Element – Knowledge” 18 Chapter 1. “Baby I Ride with My Mic in My Bra:” Nicki Minaj, Azealia Banks and the Black Female Body as Resistance 23 “Super Bass:” Black Sexual Politics and Romantic Relationships in the Works of Nicki Minaj and Azealia Banks 28 “Hey, I’m the Liquorice Bitch:” Challenging Dominant Representations of the Black Female Body 39 Fierce: Affirmation and Appropriation of Queer Black and Latin@ Cultures 43 Chapter 2. “Vamo a Vence:” Las Krudas, Feminist Activism, and Hip-Hop Identities across Borders 50 El Hip-Hop Cubano 53 Las Krudas and Queer Cuban Feminist Activism 57 Chapter 3. Coming Out and Keepin’ It Real: Frank Ocean, Big Freedia, and Hip- Hop Performances 69 Big Freedia, Queen Diva: Twerking, Positionality, and Challenging the Gaze 79 Conclusion 88 Bibliography 95 3 Introduction In 1987 Onika Tanya Maraj immigrated to Queens, New York City from her native Trinidad and Tobago with her family. Maraj attended a performing arts high school in New York City and pursued an acting career. In addition to acting, Maraj had an interest in singing and rapping. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of The Problem Social class as one of a social factor that play a role in language variation is the structure of relationship between groups where people are clasified based on their education, occupation, and income. Social class in which people are grouped into a set of hierarchical social categories, the mos common being the upper, middle, working class, and lower classes. Variation in laguage is an important topic in sociolinguistics, because it refers to social factror in society and how each factor plays a role in language varieties. Languages vary between ethnic groups, social situations, and spesific location. In social relationship, language is used by someone to represent who they are, it relates with strong identity of a certain social group. In this study the writer concern about swear words in rap song lyric. Karjalainen (2002:24) “swearing is generally considered to be the use of language, an unnecessary linguistic feature that corrupts our language, sounds unpleasant and uneducated, and could well be disposed of”. It can be concluded that swear words are any kind of rude language which is used with or without any purpose. Usually we can finds swear words on rap songs. Rap is one of elements of hip-hop culture that has been connected to the black people. The music of the artists who were born during 80’s appeared to present the music in a way that describes as a social critique. This period of artists focused on the social issue of black urban life, which later forulated hardcore activist, and gangster rap genres of hip-hop rap. -

Skyline Orchestras

PRESENTS… SKYLINE Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, you’ll be viewing the band Skyline, led by Ross Kash. Skyline has been performing successfully in the wedding industry for over 10 years. Their experience and professionalism will ensure a great party and a memorable occasion for you and your guests. In addition to the music you’ll be hearing tonight, we’ve supplied a song playlist for your convenience. The list is just a part of what the band has done at prior affairs. If you don’t see your favorite songs listed, please ask. Every concern and detail for your musical tastes will be held in the highest regard. Please inquire regarding the many options available. Skyline Members: • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES…………………………..…….…ROSS KASH • VOCALS……..……………………….……………………………….….BRIDGET SCHLEIER • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..………….…………………….……VINCENT FONTANETTA • GUITAR………………………………….………………………………..…….JOHN HERRITT • SAXOPHONE AND FLUTE……………………..…………..………………DAN GIACOMINI • DRUMS, PERCUSSION AND VOCALS……………………………….…JOEY ANDERSON • BASS GUITAR, VOCALS AND UKULELE………………….……….………TOM MCGUIRE • TRUMPET…….………………………………………………………LEE SCHAARSCHMIDT • TROMBONE……………………………………………………………………..TIM CASSERA • ALTO SAX AND CLARINET………………………………………..ANTHONY POMPPNION www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 DANCE: 24K — BRUNO MARS A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY — FERGIE A SKY FULL OF STARS — COLD PLAY LONELY BOY — BLACK KEYS AIN’T IT FUN — PARAMORE LOVE AND MEMORIES — O.A.R. ALL ABOUT THAT BASS — MEGHAN TRAINOR LOVE ON TOP — BEYONCE BAD ROMANCE — LADY GAGA MANGO TREE — ZAC BROWN BAND BANG BANG — JESSIE J, ARIANA GRANDE & NIKKI MARRY YOU — BRUNO MARS MINAJ MOVES LIKE JAGGER — MAROON 5 BE MY FOREVER — CHRISTINA PERRI FT. ED SHEERAN MR. SAXOBEAT — ALEXANDRA STAN BEST DAY OF MY LIFE — AMERICAN AUTHORS NO EXCUSES — MEGHAN TRAINOR BETTER PLACE — RACHEL PLATTEN NOTHING HOLDING ME BACK — SHAWN MENDES BLOW — KE$HA ON THE FLOOR — J. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Heather Hayes Experience Songlist Aretha Franklin Chain of Fools

Heather Hayes Experience Songlist Aretha Franklin Chain of Fools Respect Ben E. King Stand By Me Drifters Under The Boardwalk Eddie Floyd Knock On Wood The Four Tops Sugar Pie Honey Bunch James Brown I Feel Good Sex Machine The Marvelettes My Guy Marvin Gaye & Tammie Terrell You’re All I Need Michael Jackson I’ll Be There Otis Redding Sittin’ On The Dock Of The Bay Percy Sledge When A Man Loves A Woman Sam & Dave Soul Man Sam Cooke Chain Gang Twistin’ Smokey Robinson Cruisin The Tams Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy The Temptations OtherBrother Entertainment, Inc. – Engagement Contract Page 1 of 2 Imagination My Girl The Isley Brothers Shout Wilson Pickett Mustang Sally Contemporary and Dance 50 cent Candy Shop In Da Club Alicia Keys If I Ain’t Got You No One Amy Winehouse Rehab Ashanti Only You Ooh Baby Babyface Whip Appeal Beyoncé Baby Boy Irreplaceable Naughty Girls Work It Out Check Up On It Crazy In Love Dejá vu Black Eyed Peas My Humps Black Street No Diggity Chingy Right Thurr Ciara 1 2 Step Goodies Oh OtherBrother Entertainment, Inc. – Engagement Contract Page 2 of 2 Destiny’s Child Bootylicious Independent Women Loose My Breath Say My Name Soldiers Dougie Fresh Mix Planet Rock Dr Dre & Tupac California Love Duffle Mercy Fat Joe Lean Back Fergie Glamorous Field Mobb & Ciara So What Flo Rida Low Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gwen Stefani Holla Back Girl Ice Cube Today Was A Good Day Jamie Foxx Unpredictable Jay Z Give It To Me Jill Scott Is It The Way John Mayer Your Body Is A Wonderland Kanye West Flashy Lights OtherBrother Entertainment, Inc. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat.