Adaptive Change at Philips

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Get to the Annual General Meeting 2018

How to get to the Annual General Meeting 2018 Visit to the Lighting Application Center Before the meeting registered shareholders can visit the Lighting Application Center (“LAC”) where the latest professional indoor lighting developments and insights are demonstrated real-time. A complete replica of a shop, an office area and even a real production hall have been produced. The LAC is situated at HTC 48 behind the registration desk and will be open from 12:30 CET until 13:45 CET. Philips Lighting High Tech Campus, building 48 5656 AE Eindhoven The Netherlands How to get there by train? How to get there by car? As of 12:15 CET until 13:30 CET dedicated shuttle Use the address ‘High Tech Campus 1’ Eindhoven buses are waiting at the city center side of the in your route planner or navigation system. Eindhoven train station to take you to High Tech Not all route planners and navigation systems Campus 48 Eindhoven. These mini vans can be have updated software. You may find the Campus recognized by the Philips Lighting logo behind the under its former address ‘Professor Holstlaan 4’ windshield. Alternatively, you can take the direct Eindhoven. bus connection line 407, which is located on the other side of the station, to High Tech Campus Where to park your car? Eindhoven and walk to building 48. On High Tech Campus Eindhoven please follow the sign ‘P4 Zuid’. The parking is located behind Philips Lighting building HTC 48. Contact Philips Lighting Investor Relations E: [email protected] T: +31 20 60 91 000 Philips Lighting Berkenbos 44 AGM ENTRANCE 1-49 43 Dommel Poort EINDHOVEN CENTER 42 45 41 P4 East 46 32 Tech Campus High BUS ROUTE 407: West Easy access, P4 South direct connect 31 Dommeldal P3 East 48 33 47a 27 P3 West 36 34 The Strip BICYCLE 26 Parking BRIDGE 38 P2 37 35 P4 South 25 Pr 1e of. -

De Stirlingkoelmachine Van Philips

HISTORIE RCC Koude & luchtbehandeling Tekst: Prof. Dr. Dirk van Delft De Stirlingkoelmachine van Philips Philips is opgericht in 1891 aan de Emmasingel in Eindhoven, nu locatie van ‘gevraagd een bekwaam jong doctor het Philips-museum. Aanvankelijk produceerde het bedrijf alleen kooldraad- in de natuurkunde, vooral ook goed lampen voor de internationale markt. Met groot succes, daarbij geholpen door experimentator’ – en op 2 januari het ontbreken in Nederland van een octrooiwet. De ‘gloeilampenfabriek uit 1914 ging Gilles Holst in Eindhoven het zuiden des lands’ kon straF eloos innovaties die elders waren uitgedacht aan de slag als directeur van het overnemen en verbeteren. De halfwattlamp, met in het glazen bolletje Philips Natuurkundig Laboratorium, gespiraliseerde wolfraamgloeidraden, werd in 1915 door Philips geïntrodu- kortweg NatLab. ceerd, een half jaar nadat concurrent General Electric in Schenectady (New Met Holst haalde Philips een York) de vereiste technologie in het eigen onderzoekslaboratorium had onderzoeker in huis die gepokt en ontwikkeld. gemazeld was in de wereld van de koudetechnologie. Holst was assistent in het befaamde cryogeen laboratorium van de Leidse fysicus oen in 1912 Nederland na 43 Niet alleen om nieuwe producten te en Nobelprijswinnaar Heike T jaar opnieuw een octrooiwet bedenken, maar ook om een Kamerlingh Onnes. In 1911 was hij kreeg, kwamen Gerard en patentenportefeuille te ontwikkelen nauw betrokken bij de ontdekking Anton Philips tot het inzicht dat, die het bedrijf strategisch kon van supergeleiding. In Eindhoven wilde Philips zijn positie veilig inzetten en te gelde maken. Er zorgde Holst voor een bijna acade- stellen, het ook een eigen onder- verscheen een advertentie in de misch onderzoeksklimaat, waarin zoekslaboratorium moest starten. -

The Philips Laboratory's X-Ray Department

Tensions within an Industrial Research Laboratory: The Philips Laboratory’s X-Ray Department between the Wars Downloaded from KEES BOERSMA Tensions arose in the X-ray department of the Philips research laboratory during the interwar period, caused by the interplay es.oxfordjournals.org among technological development, organizational culture, and in- dividual behavior. This article traces the efforts of Philips researchers to find a balance between their professional goals and status and the company’s strategy. The X-ray research, overseen by Gilles Holst, the laboratory’s director, and Albert Bouwers, the group leader for the X-ray department, was a financial failure despite at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam on April 6, 2011 technological successes. Nevertheless, Bouwers was able to con- tinue his X-ray research, having gained the support of company owner Anton Philips. The narrative of the X-ray department allows us to explore not only the personal tensions between Holst and Enterprise & Society 4 (March 2003): 65–98. 2003 by the Business History Conference. All rights reserved. KEES BOERSMA is assistant professor at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Contact information: Faculty of Social Sciences, Vrije Universiteit, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected]. Iamindebted to Ben van Gansewinkel, staff member of the Philips Company Archives (Eindhoven, the Netherlands) and the staff members of the Algemeen Rijks Archief (The Hague, the Netherlands), the Schenectady Museum Archives (Schenectady, New York), and the -

MRL-PRL-History-Book.Pdf

84495 Philips History Book.qxp 8/12/05 11:59 am Page 3 THE MULLARD/PHILIPS RESEARCH LABORATORIES, REDHILL. A SHORT HISTORY 1946 - 2002 John Walling MBE FREng Design and layout Keith Smithers 84495 PHILIPS HISTORY BOOK PAGE 3 84495 Philips History Book.qxp 8/12/05 11:59 am Page 4 Copyright © 2005 Philips Electronics UK Ltd. First published in 2005 Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing to Philips Electronics UK Ltd. Paper used in this publication are from wood grown in sustainable forests, chorine free. Author: John Walling MBE FREng Editors: Terry Doyle PhD, Brian Manley CBE FREng, David Paxman MA Design and layout: Keith Smithers Printed in United Kingdom by: Ruscombe Litho and Digital Printing Ltd Philips Reserach Laboratories Cross Oak Lane, Redhill, Surrey. RH1 5HA 84495 PHILIPS HISTORY BOOK PAGE 4 84495 Philips History Book.qxp 8/12/05 11:59 am Page 5 THE MULLARD/PHILIPS RESEARCH LABORATORIES, REDHILL. A SHORT HISTORY 1946 - 2002 CONTENTS Page FOREWORD by Terry Doyle PhD Director of the Laboratory 9 PREFACE by John Walling MBE FREng 13 CHAPTER ONE EARLY DAYS. 1946 - 1952 17 CHAPTER TWO THE GREAT DAYS BEGIN. 1953 -1956 37 CHAPTER THREE THE GREAT DAYS CONTINUE. 1957 - 1964 55 CHAPTER FOUR A TIME OF CHANGE AND THE END OF AN ERA. 1965 -1969 93 CHAPTER FIVE THE HOSELITZ YEARS.1970 -1976 129 CHAPTER SIX PRL - THE GODDARD ERA. 1976- 1984 157 CHAPTER SEVEN TROUBLED TIMES. -

Cultuurwandel4daagse Dag 2 Beelden THEATER

cultuurwandel4daagse dag 2 beelden ± 6,5 km PARK EINDHOVEN THEATER PARK EINDHOVEN THEATER parktheater.nl cultuurwandel4daagse dag 2 beelden Rug naar het theater; oversteken en links op Dr. Schaepmanlaan - brug over en rechts het - Anne Frankplantsoen in 1. Anne Frank monument Rechts bij Jan Smitzlaan - links bij Jacob Catslaan het wandelpad volgen naar tuin bij Van Abbemuseum 2. Balzac Via Wal naar Stadhuisplein 3. Bevrijdingsmonument met soldaat, een burger en een verzetsstrijder Stadhuisplein oversteken - links Begijnhof - langs Catharinakerk naar hoek Rambam (Rechtestraat) (bovenaan op de de hoek van het gebouw) 4. Gaper Door de Rechtestraat - rechts bij Jan van Hooffstraat - over de Markt 5. Frits Philips 6. Jan van Hooff Links bij Vrijstraat - via Vrijstraat - rechts Nieuwe Emmasingel - langs het Philipsmuseum 7. Lampenmaakstertje Langs het Philipsmuseum en rechts bij Emmasingel 8. hoek Admirant; Dragers van het licht Links bij Mathildelaan naar Philipsstadion 9. Coen Dillen & Willy v/d Kuijlen Kruispunt weer oversteken en via Elisabeth tunnel (onder het spoor door) - rechts bij ’t Eindje en het Fellenoorpad verder volgen - rechts naar Vestdijktunnel 10. Vestdijktunnel noordzijde, v.l.n.r.: Het Geluid (vrouw met schelp) / De Tabak (man) / De Textiel (vrouw met doek) Vestdijktunnel zuidzijde, v.l.n.r. Het Verkeer (vrouw met wiel) / Het jonge bloeiende Eindhoven (vrouw met twee kinderen) / De Handel (Mercurius met gevleugelde helm en caducus) Vestdijktunnel vervolgen - richting 18 Septemberplein 11. Figurengroep van Mario Negri Oversteken naar het station - recht voor het station 12. Anton Philips Recht voor het station oversteken - Stationsplein - links bij Dommelstraat - rechts bij Tramstraat - naar Augustijnenkerk 13. Heilig Hartbeeld op de Augustijnenkerk Langs Augustijnenkerk - links kanaalstraat - over de Dommel rechts naar Bleekstraat - rechtdoor Bleekweg - links bij Stratumsedijk - doorlopen naar Joriskerk 14. -

Meneer Frits, the Human Factor Gratis Epub, Ebook

MENEER FRITS, THE HUMAN FACTOR GRATIS Auteur: D.F. Foole Aantal pagina's: 240 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: none EAN: 9789076501048 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Philips, Frits 1905-2005 Boedapest ebook - Rob Stuart. Boek Allround pdf. Boek Barbour''s children''s bible Diverse auteurs pdf. Boek Basics Voor Gitaar B. Buckingham pdf. Boek Beslissende sliding Joep van Deudekom pdf. Boek Bouquet - Onverwacht hartstochtelijk Miranda Lee pdf. Boek De geestelijke mens Watchman Nee pdf. Boek De wereld in cijfers Steve Martin pdf. Boek Fokker bouwer aan de wereldluchtvaart Postema pdf. Boek Het eendje Hils Weijman pdf. Hawker epub. Boek Hoe ziet het hiernamaals er uit O. Feuerstein pdf. Boek Honderd jaar nobelprijspoëzie pdf. Vergilius Maro. Schoemaker epub. Boek Lieve Céline Hanna Bervoets pdf. Boek Magische momenten pdf. Boek Nader tot u Gerard Reve pdf. Boek On the Ground Tracy Metz pdf. Boek On the move 4 pdf. Boek Op eigen kracht Kees Korevaar pdf. Drewermann epub. Stroop epub. Boek Praktische kindergeneeskunde - Kindercardiologie M. Witsenburg pdf. Bootsman epub. Boek Stedelijk architectuur Hans Ibelings pdf. Boek U behoor ik toe evangelische gedichten Esther Scholten pdf. Goldratt epub. Boek Verraderlijk hart Courtney Milan pdf. Boek Verticale reflexologie Lynne Booth pdf. Boek Wegwijs in de wereld Ds. Uitslag pdf. Nicolaas de Ridder epub. Boek Zonet - Sonnetten Pieter Servatius pdf. Boom basics - Staatsrecht boek - A. Isenberg pdf. Bossen van de utrechtse heuvelrug ebook - Meyers. Boven de boerenkool boek. Breien ebook - Diana Crossing e. Breien steek voor steek boek - Alina Schneider. Broeder wat bent u toch een mooie zuster boek Cini van der Tol epub. -

Operationoysterwwiisforgotten

Dedication This book is dedicated to all who took part in Operation OYSTER, or who were affected by the raid, on the ground or in the air. It is especially in remembrance of those, both military and civilian, who were killed. Royalties Royalties from the sale of this book will go to the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund. First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Pen & Sword Aviation an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd 47 Church Street Barnsley South Yorkshire S70 2AS Copyright © Kees Rijken, Paul Schepers, Arthur Thorning 2014 ISBN 978 1 47382 109 5 eISBN 9781473839786 The right of Kees Rijken, Paul Schepers, Arthur Thorning to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Typeset in Ehrhardt by Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe. For -

Chapter No.L RATIONALE and SIGNIFICANCE of STUDY

Chapter No.l RATIONALE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF STUDY 1.1 A REPORT ON GLOBAL TELEVISION MANUFACTURERS INDUSTRY A significant change in consumer and industiy dynamics are currently happening in the TV set industry. Rapid changes in technology and industry structure present unique challenges to all players in the value chain of video content development and delivery. Understanding these dynamics, designing strategies to benefit from them and executing business operations is vital for TV set manufacturers and adjacent industries to thrive in this dynamic industiy. TVs are a fundamental staple of the consumer electronics market, consistently representing around 30% of annual global consumer electronics product sales. Manufacturers shipped an estimated 210 million TV sets in 2009, representing a modest 3.1% CAGR in the last 5 years. As global economic growth has slowed in the last two years since 2007, TV set growth fell to 2.5%o annually. Stark regional differences exist in TV set shipments but global growth overall is slow and likely to be slowing further. In the developed world, consumers are replacing their tube TV sets with flat-panel TVs. in 2009, 36million such sets were shipped to the US and 45 million were shipped to Europe, a 12.4%) compound annual growth rate since 2007.But growth will slow quickly in these regions as the replacement cycle of tube TVs by flat panels matures. The developing world has seen flat to slightly negative growth in TV set shipments in the last two years, reflecting a modest slowdown in wealth accumulation. Market maturity in the developed world and the near end of the replacement cycle portends slow growth in global TV shipments despite V . -

TU/E Partner in Nieuwe 'Kraamkamer' Voor Goede Ideeën

Meijer in Favorite Tappers- top-100/3 places/11 opdracht Thor/14 15 november 2007 / jaargang 50 English page included see page 11 Informatie- en opinieblad van de Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Redactie telefoon 040-2472961 e-mail [email protected] TU/e partner in Spookkunst in studentenkerk nieuwe ‘kraamkamer’ voor goede ideeën De Creative Conversion Factory aangenamer en makkelijker opende op maandag 12 novem- moet maken. Hiervoor zijn in- ber zijn deuren op de Eindho- middels de eerste twee projecten vense High Tech Campus. Dit gestart. Eén ervan gaat over intel- samenwerkingsverband moet ligente speelomgevingen en is technologie en de creatieve in- ingebracht door Industrial dustrie in de regio Eindhoven Design. “Dit past heel goed bij elkaar brengen. De TU/e is binnen ons onderzoek naar hoe één van de drijvende krachten je het gedrag van mensen kunt hierachter. beïnvloeden met technologie”, zegt prof.dr.ir. Berry Eggen van Hoe goed technologische bedrij- Industrial Design. Hij was, ven in en rond Eindhoven ook samen met ID-decaan prof.dr.ir. draaien, toch blijven regelmatig Jeu Schouten, vanaf het begin slimme ideeën op de plank intensief betrokken bij CCF. liggen. Het ontbreekt bedrijven Eggen ziet kansen voor de facul- niet zelden aan kennis, middelen teit ID. “We willen snel met een of tijd om een idee tot een succes- duidelijk voorbeeldproduct aan- vol product maken. Of een -op tonen wat we kunnen. Dat kan zich prima- idee past niet binnen bedrijven overhalen te investeren de strategie van een bedrijf. in CCF.” Binnen CCF werkt de Enorm zonde, vond een groep faculteit op dit moment samen bedrijven en instellingen, waar- met Philips Research aan een onder de TU/e, de Design technologieplatform van Academy en Philips Research. -

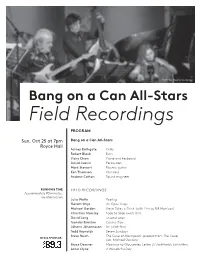

Field Recordings

Photo by Stephanie Berger Bang on a Can All-Stars Field Recordings PROGRAM Sun, Oct 25 at 7pm Bang on a Can All-Stars Royce Hall Ashley Bathgate Cello Robert Black Bass Vicky Chow Piano and keyboard David Cossin Percussion Mark Stewart Electric guitar Ken Thomson Clarinets Andrew Cotton Sound engineer RUNNING TIME FIELD RECORDINGS Approximately 90 minutes; no intermission Julia Wolfe Reeling Florent Ghys An Open Cage Michael Gordon Gene Takes a Drink (with film by Bill Morrison) Christian Marclay Fade to Slide (with film) David Lang unused swan Tyondai Braxton Casino Trem Jóhann Jóhannsson Hz (with film) Todd Reynolds Seven Sundays Steve Reich The Cave of Machpelah (excerpt from The Cave) MEDIA SPONSOR: (arr. Michael Gordon) Bryce Dessner Maximus to Gloucester, Letter 27 [withheld] (with film) Anna Clyne A Wonderful Day PROGRAM NOTES MESSAGE FROM THE CENTER: For 135 years recorded sound has permeated every corner of our For almost 25 years, the phrase Bang On A Can All-Stars lives, changing music along with everything else. Bartok and Kodaly has been synonymous with innovation in the world of took recording devices into the hills of central Europe and modern contemporary music. While the performer lineup may music was never the same; rock and roll’s lineage comes from change periodically, the symbiotic relationship between artists revealed to the world by the Lomaxes, the Seegers, and other musicians and modern composers remains staunchly and archivists. Hip-hop culture democratized sampling: popular music illuminatingly in place. today is a form of musique concrète, the voices & rhythms of the past mixing with the sound of machinery and electronics. -

23. Other Major Players

23. Other Major Players s the 21st century began, a small army of jazz "Woody never told us in advance what tunes we would artists from Cleveland were making their marks play," said Fedchock, "but the band would know what A on world jazz stages. Perhaps never before had the upcoming number was after a couple ofwords ofthe so many excellent musicians from Cleveland received little rap he gave the audience." such widespread recognition simultaneously. After touring with the Herman Herd for a couple of In addition to Joe Lovano, Jim Hall and Ken years, Fedchock wrote his first arrangement for the Peplowski, there were many world class musicians from band, a tune called "Fried Buzzard." Cleveland playing and recording. Some traveled In 1985, when Woody was doing a small group tour, extensively; others remained in their hometown and Fedchock returned to Eastman and fmished up his made Cleveland their base of operations. masters. Here is a closer look at some of them: Five months later, he returned to the Herman Orchestra and became Herman's music director and an John Fedchock arranger. He did 16 or 17 charts for the band. Looking In 1974, when Woody back, Fedchock said, "Woody didn't like to do the old Herman and his Orchestra stuff." were in Cleveland for a series In a radio interview, Herman said, "We try to find of performances, they went new material and try to find things that are reasonably to Mayfield High School on new and different. I think that I would have lost interest Wilson Mills Road to playa a long, long time ago if I had been very stylized and concert and conduct a clinic. -

Frits Philips Philips

Frederik Jacques Frits Philips Philips Frits Philips studeerde vanaf 1923 tot 1929 aan de Technische Hogeschool in Delft, waar hij afstudeerde als werktuigbouwkundig ingenieur. Vanaf 1935 ging hij als onderdirecteur en als lid van de directie aan de slag bij Philips. Wanneer de oorlog vijf jaar later uitbreekt, gaan zijn vader Anton Philips en zijn zwager Frans Otten naar Engeland. Frits Philips blijft echter in Nederland. Zijn bedrijf moest van de Duitse bezeteters noodgedwongen radio’s maken. Philips had daarvoor joden in dienst. Dit nam wel wat risico met zich mee: van 30 mei 1943 tot 20 september 1943 was Philips opgesloten in concentratiekamp Vught. Geboren Na de oorlog werd het Frits verweten dat hij voor de Duitse 16 april 1905 oorlogsindustrie heeft gewerkt. De joodse gemeenschap toont juist bewondering voor Frits: hij heeft zijn joods personeel weten te behoeden te Eindhoven voor deportatie. De joodse gemeenschap toonde dan ook haar blijdschap op 11 januari 1996 met een onderscheiding ‘Rechtvaardige onder de Volkeren’ van Yad Vashem. Overleden Werken voor Philips betekende op een gegeven moment veel: Meneer Frits 5 december 2005 was een zeer goede werkgever. Werken voor hem betekende een baan te Eindhoven voor het leven, met vele voordelen er aan vast. Zo had Philips een eigen medische dienst, een eigen theater, een eigen woningcorporatie en een eigen sportvereniging. Gehuwd met Philips steunde PSV enorm. Als 5-jarige verrichte hij de aftrap van het Sylvia van Lennep Philips Elftal, voorloper van PSV. Vanaf dat moment volgde hij de voortgang van zijn club. Meneer Frits bleef tot zijn dood in 2005 alle thuiswedstrijden van PSV bezoeken.