MAMU Catalogue July 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNIVERSITY of MELBOURNE ANNUAL REPORT Report of the Proceedings of the University for the Year Ended 31St December, 1949

THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE ANNUAL REPORT Report of the Proceedings of the University for the year ended 31st December, 1949. To His Excellency, Sir Dallas Brooks, K.C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O.,, Governor of Victoria. May it Please Your Excellency, I have the honour, in accordance with Section 43 of the Uni versity Act 1928, to submit to Your Excellency the following report of the Proceedings of the University during 1949. 1. Student Numbers: The first falling off in numbers, since the post-war inflation, took place in 1949 when the total number of students was 9,254 compared with 9,497 in 1948. This was the direct result of the reduction of ex-service entries from 3,770 in 1948 to 3,460 in 1949. The 1950 enrolments are bound to recede sharply and 1951 will probably see the lowest point of the recession in as much as our recent surveys, which are similar to those prepared by the Universities Commission for all Australian Universities, indicate that numbers will start to rise again in 1952. The restrictions on entry remained as in 1948 and applied only to the second year of the Medical Course (42 students who had passed First Year being deferred till 1950) and to the "extra-Victorian quota" in the first year. 2. Staff: The size of the University can be measured to some extent by the number of those on the pay-roll, which increased from 1,344 in 1948 to 1,534 in 1949 (1,186 full-time and 348 part-time). -

Publications for Jeanell Carrigan 2021 2020 2019

Publications for Jeanell Carrigan 2021 Carrigan, J., Caillouet, J. (2021). Innovation. In Anna Reid, Carrigan, J. (2020). The Composers' Series: Volume 8 (a) - Neal Peres Da Costa, Jeanell Carrigan (Eds.), Creative Piano Solos Advanced - Frank Hutchens [Portfolio]. The Research in Music: Informed Practice, Innovation and Composers' Series: Volume 8 (a) - Piano Solos Advanced - Transcendence, (pp. 95-99). New York, USA: Routledge. <a Frank Hutchens, (pp. vi - 103). Wollongong, Australia: href="http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780429278426-10">[More Wirripang Pty Ltd. Information]</a> Carrigan, J. (2020). The Composers' Series: Volume 8 (b) - 2020 Piano Solos Intermediate - Frank Hutchens [Portfolio]. The Composers' Series: Volume 8 (b) - Piano Solos Intermediate - Carrigan, J. (2020). Sea Impressions: Piano Miniatures by Frank Hutchens, (pp. vi - 71). Wollongong, Australia: Australian Composers, Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang Pty Wirripang Pty Ltd. Ltd. Carrigan, J. (2020). The Composers' Series: Volume 9 Piano Carrigan, J. (2020). Reverie: Piano Music by Australian Solos - Lindley Evans [Portfolio]. The Composers' Series: Women, CD, Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang. Volume 9 Piano Solos - Lindley Evans, (pp. 1 - 81). Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang. Carrigan, J., Choe, M. (2020). [1-3] Sonata for Cello and Piano: Allegro ritmico; Lento; Allegro [5-8] Four Aspects: Grieving; 2019 Stress; Hope; Healing [10] An Evening Stroll [11] The Lake [12] Nocturne for Piano Carrigan, J. (2019). Meta Overman: Sonata for Viola and [Portfolio]. On In Tribute: Music by Dulcie Holland, CD, Piano, (pp. 1 - 28). Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang Pty Ltd. Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang Media Pty Ltd. Carrigan, J. (2019). 1. Scherzo No. 1 in B minor, 3. Through Richter, G., Carrigan, J., Choe, M. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright ALFRED HILL’S VIOLA CONCERTO: ANALYSIS, COMPOSITIONAL STYLE AND PERFORMANCE AESTHETIC Charlotte Fetherston A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, NSW 2014 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. -

F Te Hititomts of Iulbonrnt 1939

f te Hititomts of iUlbonrnt 1939. VISITOR. HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR OF VICTORIA. COUNCIL. CHANCELLOR SIR JAMES WILLIAM BARRETT, K.B.E., C.B., C.M.G., LL.D. (Manitoba), M.D., M.S. (Melb.), F.R.A.C.S., F.R.C.S. (Eng.), C.M.Z.S. Elected 30th August, 1935. DEPUTY-CHANCELLOR. RT. HON. SIR JOHN GREIG LATHAM, P.C, G.C.M.G., K.C., M.A., LL.M. Elected 30th August, 1935. VICE-CHAN CELLOR. JOHN DUDLEY GIBBS MEDLEY, M.A. (Oxon). MEMBERS. Appointed by the Governor-in-Council, 17th December, 1935— HON. JOHN PERCY JONES, M.L.C. Originally appointed 11th July, 1923. HON. SIR STANLEY SEYMOUR ARGYLE, K.B.E., M.L.A., M.B.. B.S. Originally appointed 15th September, 1927. SIR WILLIAM LENNON RAWS, KT.B., C.B.E. Originally appointed 12th December, 1928. HON. JOHN LEMMON, M.L.A. Originally appointed, 19th July, 1932. CHARLES HAROLD PETERS, M.C. Originally appointed Sth December, 1932. JAMES MACDOUGALL, Originally appointed Uih August, 1933. HON. PERCY JAMES CLAREY, M.L.C. 19th December, 1938— JOSEPH EDWIN DON. Elected by Convocation, 17th December, 1935— MR. JUSTICE CHARLES JOHN LOWE, M.A., LL.B. Originally elected 10th February, 1927. JAMES RALPH DARLING, M.A. (Oxon and Melb,). Originally elected 31st October, 1933. MORRIS MONDLE PHILLIPS, M.A. Originally elected 13th November, 1934. BERNARD TRAUGOTT ZWAR, M.D., M.S., F.R.A.C.S. Originally elected 7th May, 1935. WILFRF.D RUSSELL GRIMWADE, C.B.E., B.Sc. Originally elected 13th August, 1935. Elected by Convocation, 16th December, 1937— SIR JAMES WILLIAM BARRETT, K.B.E. -

Etruscan Concerto

476 3222 PEGGY GLANVILLE-HICKS etruscan concerto TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA As a still relatively young nation, Australia could composing that they had no option but to go be considered fortunate to have collected so away. Equally true, relatively few of our few notable dead composers! For most of the composing women flourished ‘abroad’ for long, 20th century, almost every composer we could though Tasmanian Katharine Parker (Longford- claim was very much alive. Yet, sadly, this did born and Grainger protégée) did, and Melburnian not stop us from losing track of some of our Peggy Glanville-Hicks is the notable other. Peggy Glanville-Hicks 1912-1990 most talented, who went away and stayed Indeed, Edward Cole’s notes for the 1956 away, as did Percy Grainger and Arthur Benjamin American first recording of her Etruscan Etruscan Concerto [15’17] (the only Australian composer blacklisted by Concerto make the unique claim: ‘Peggy 1 I. Promenade 4’05 Goebbels), or returned too late, like Don Banks. Glanville-Hicks is the exception to the rule that 2 II. Meditation 7’26 And we are now rediscovering many other women composers do not measure up to the 3 III. Scherzo 3’46 interesting stay-aways, like George Clutsam (not standards set in the field by men.’ Caroline Almonte piano just the arranger of Lilac Time), Ernest Hutchinson, John Gough (Launceston-born, like Talented Australian women of Glanville-Hicks’ 4 Sappho – Final Scene 7’42 Peter Sculthorpe) and Hubert Clifford. generation hardly lacked precedent for going Deborah Riedel soprano Meanwhile, among those who valiantly toiled abroad, as Sutherland, Rofe and Hyde all did for away at home, we are at last realising that a while, with such exemplars as Nellie Melba 5 Tragic Celebration 15’34 names like Roy Agnew, John Antill and David and Florence Austral! Peggy Glanville-Hicks’ Letters from Morocco [14’16] Ahern might not just be of local interest, but piano teacher was former Melba accompanist 6 I. -

Canzonetta Canzonetta Iris De Cairos-Rego

Canzonetta Canzonetta Iris de Cairos-Rego Cairos-Rego Iris de Cairos-Rego was a 20th-century Australian composer, pianist and teacher. She was born in 1894. Her father, George, a composer and music critic who was a driving force behind the establishment of the Sydney Conservatorium, was her first teacher. She under- took further studies in Berlin and London from 1907 to 1910. Returning to Australia, Cairos- Rego taught piano at the newly established Conservatorium in Sydney, and at Frensham School in Mittagong. She frequently performed as a piano soloist and chamber musician, including concerto performances with the Conservatorium Orchestra, ABC radio broadcasts, and as an associate artist with her brother, Rex, who was a singer. She died in 1987.1 Cairos-Rego’s compositions Cairos-Rego’s compositions were mostly for piano; they include: • Arabesque in A minor. • Canzonetta. • English June. • Firelight. • A frolic. • Graneen Vale. • Four sketches: Waltz in A, Song of the trees, Little dog and Country dance. • Tarrel (a highland song). • Toccata (The train). • Waltz caprice. • White cloud. • Bushland Sketches for piano duet. Cairos-Rego’s contemporaries • Roy Agnew (Australian, 1891-1944). • Mirrie Hill (Australian, 1892-1986). • Frank Hutchens (Australian, 1892-1965). • Arthur Benjamin (Australian, 1893-1960). • Lili Boulanger (French, 1893-1918). • Lindley Evans (Australian, 1895-1982). • Margaret Sutherland (Australian, 1897-1984). • Linda Phillips (Australian, 1899-2002). • Esther Rofe (Australian, 1904–2000). • Dulcie Holland (Australian, 1913-2000). • Miriam Hyde (Australian, 1913-2005). 1 For further information about the composer, see www.dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/de_cairos-rego_iris or www.musicaustralia.org. Copyright © 2012 by R. A. Hamilton Canzonetta Title A canzonetta is a short song, or a song-like piece, where the melody is always in the upper voice. -

The Impact of Russian Music in England 1893-1929

THE IMPACT OF RUSSIAN MUSIC IN ENGLAND 1893-1929 by GARETH JAMES THOMAS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham March 2005 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is an investigation into the reception of Russian music in England for the period 1893-1929 and the influence it had on English composers. Part I deals with the critical reception of Russian music in England in the cultural and political context of the period from the year of Tchaikovsky’s last successful visit to London in 1893 to the last season of Diaghilev’s Ballet russes in 1929. The broad theme examines how Russian music presented a challenge to the accepted aesthetic norms of the day and how this, combined with the contextual perceptions of Russia and Russian people, problematized the reception of Russian music, the result of which still informs some of our attitudes towards Russian composers today. Part II examines the influence that Russian music had on British composers of the period, specifically Stanford, Bantock, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Frank Bridge, Bax, Bliss and Walton. -

Ruby Rich Schalit Womens Contribution to Music in AU.Pdf (PDF, 2.35MB)

WOMEN 1S CONTRIBUTION TO MUSIC IN .AU�'TRALIA Women have contributed to music in Auatralia in a wide field of endeavour. The Billiers, composers, instnimentalists, teachers, administrators and musicolo�ists have all played their part in Australian history and can lay claim to a place on the honours board of their couatry. AM brevity i• the keynote of this report it must of necessity b� selective. I have therefore endeavoured to catalo�ue only some of the outstandiDi women who have helped to make Australia known internationally or who have been responsible for some historic landmark within Australia. The list has been arr&D&ed chronolo�ically to create a aenae of histor�cal deve lopnent. ************************************* ... ;- . \ EMJ\l!ELINE M. WOOLLEY On 29 June, 1895 it was reported in the Sydney Mail a the pleasure · 'for the first· time in the history of N.S.W. we h ve d w r d to record an event which is by no means common,in the o� o l in namely, the production of an orig al cantata by two ladies. verses , The composer , Emmeline Woolley and the author of the Pedl.ey,are professors of music resident in Sydney.• Miss Ethel ,, Emmeline Woolley who gained this notoriety was a person was f d in of diverse musical attributes. She born in Here or appointment 1843 and came to Australia as a very young girl upon the f of her father, Dr. John Woolley, as the first principal o the University of Sydney. Her earliest I'ecollections were of Norwich, where Dr. -

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

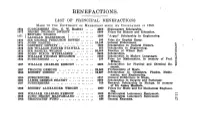

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

1 3 October 2008 SELECT LIST of WORKS

Australian Music Centre, PO Box N690 Grosvenor Place, NSW, 1220 email: [email protected] web: http://www.amcoz.com.au phone: (02) 9247 4677 or 1300 651 834 This list includes scores suitable for HSC performance and available for purchase or borrowing from the Australian Music Centre. Where available, library numbers for matching recordings have also been listed (eg. CD245 or C2003). 3 October 2008 SELECT LIST OF WORKS WRITTEN IN THE LAST 25 YEARS FOR VOICE HELD AT THE AUSTRALIAN MUSIC CENTRE LIBRARY (PLEASE NOTE: this list includes works for voice with piano only. If you are looking for works with accompaniment other than piano, please contact the Centre) ALLEN, GEOFFREY Bredon Hill, opus 10 : eight songs for tenor voice and piano to poems of A. E. Housman / by Geoffrey Allen. - 1995 Perth : Keys Press, 1995. 1 score (36 p.) ; 30 cm. Tenor voice, piano. When I came last to Ludlow -- Loveliest of trees -- Twice a week the winter thorough [sic] -- Reveille -- On the idle hill of summer -- White in the moon -- 'Tis time I think -- Bredon Hill. 783.87542/ALL 1 CD 1337 Four songs : to poems of Rosemary Dobson / by Geoffrey Allen. - 2006 Perth : Keys Press, 2006. 1 score (20 p.) ; 30 cm. ISMN: M-720052-55-7 Keys Press: KP 0278. Voice, piano. 1. A fine thing -- 2. The bystander -- 3. The alphabet -- 4. Ampersand. Includes programme notes. 783.2542/ALL 1 Songs that mother never taught me, opus 17 : for soprano and piano / by Geoffrey Allen. - 1993 Perth : Keys Press, 1993. 1 score (25, [i], p.) ; 30 cm. -

Australian Chamber Music with Piano

Australian Chamber Music with Piano Australian Chamber Music with Piano Larry Sitsky THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Sitsky, Larry, 1934- Title: Australian chamber music with piano / Larry Sitsky. ISBN: 9781921862403 (pbk.) 9781921862410 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Chamber music--Australia--History and criticism. Dewey Number: 785.700924 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Preface . ix Part 1: The First Generation 1 . Composers of Their Time: Early modernists and neo-classicists . 3 2 . Composers Looking Back: Late romantics and the nineteenth-century legacy . 21 3 . Phyllis Campbell (1891–1974) . 45 Fiona Fraser Part 2: The Second Generation 4 . Post–1945 Modernism Arrives in Australia . 55 5 . Retrospective Composers . 101 6 . Pluralism . 123 7 . Sitsky’s Chamber Music . 137 Edward Neeman Part 3: The Third Generation 8 . The Next Wave of Modernism . 161 9 . Maximalism . 183 10 . Pluralism . 187 Part 4: The Fourth Generation 11 . The Fourth Generation . 225 Concluding Remarks . 251 Appendix . 255 v Acknowledgments Many thanks are due to the following. -

% Be Mnitorsitp of Jwboiinw 1940

% be Mnitorsitp of jWboiinw 1940 VISITOR. HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR OF VICTORIA. CHANCELLOR. RT. HON. SIR JOHN GREIG LATHAM, G.C.M.G., M.A., LL.M. Elected 6th March, 1939. DEPUTY-CHANCELLOR. SIR WILLIAM LENNON RAWS, Kt.B., C.B.E. Elected 6th March, 1939. VICE-CHANCELLOR. JOHN DUDLEY GIBBS MEDLEY. M.A. (Oion and Melb.). Appointed 1st July. 1938. COUNCIL. Appointed by the Governor-in-Council (present term expires 17th December, 1943)— • HON. HERBERT HORACE OLNEY, M.L.C. Appointed 17th December, 1939. "FRANCIS FIELD, M.L.A., M.A., LL.B. Appointed 17th December, 1939. • TREVOR DONALD OLDHAM, M.L.A., LL.B. Appointed 17th December, 19J9. SIR WILLIAM LENNON RAWS, KT.B.. C.B.E. Originally appointed 12th December, 1928. / JAMES MACDOUGALL. Originally appointed 14th August, 1933. JOSEPH EDWIN DON. Originally appointed 19th December, 1938. • HERBERT JOHN OKE. Appointed I7th December, 1939; previously appointed 21st November, 1933. ROY GEORGE PARSONS. Appointed 17th December, 1939. Elected by Convocation— Term expiring 17th December, 1941—- • SIR JAMES WILLIAM BARRETT, K.B.E.. C.B., C.M.G., LL.D. (Manitoba), M.D., M.S. (Melb.), F.R.A.C.S., F.R.C.S, Eng., C.M.Z.S. Originally elected 10th January, 1901. • RT. HON. SIR IOHN GREIG LATHAM, G.C.M.G., M.A., LL.M. Originally eiectcd 15th April, 1922. • GEORGINA SWEET, O.B.E., D.Sc. Originally elected Sth December, 1936. CHARLES HALLILEY KELLAWAY, M.C, M.D., M.S., F.R.S. Elected 16th December. 1937. • JOHN ALBERT LAING, M.C.E. Elected 25th July, 1939.