Elizabeth Mitchell Thesis VMTA May 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forty Thousand Horsemen Music Credits

Musical Score Lindley Evans in collaboration with Willy Redstone • Alfred Hill Harry Lindley Evans was a pianist, and amongst many other musical things, an accompanist for Dame Nellie Melba. The ADB contains a detailed biography. Evans alternated between working for Chauvel and producer director Ken G. Hall at Cinesound. He first worked with Chauvel on Uncivilised. Evans also has a wiki here, and there is a short form biography here (there's also a sample of one of his works at this location) which reads: Lindley Evans, born in Capetown on 18th November, 1895, began his musical career very early, and at nine was already a member of St. George's Cathedral choir, Capetown. He later became a timpanist, but after moving to Australia in 1912 he studied piano performance and composition with Frank Hutchens at the NSW Conservatorium of Music. He was to play together with Frank Hutchens as duo- pianists for 40 years until Hutchens' death in 1965 in a car accident. After his studies with Hutchens, Evans later went to study in London with Tobias Matthay. For many years, from 1922, Evans was accompanist to Dame Nellie Melba. As a leader of the Australian Music Camp movement, as the "Melody Man" on the ABC Children's Session, and as duo-pianist with Hutchens, Lindley Evans became known to thousands of Australian music lovers, young and not so young. He met with pianist Isador Goodman in 1930 upon Goodman's appointment to the NSW Conservatorium and they remained friends to their deaths, within hours of each other, on 2nd December, 1982. -

'And There Came All Manner of Choirs:' Melbourne's Burgeoning Choral Scene Since 1950 *

SYMPOSIUM: CHORAL MUSIC IN MELBOURNE ‘And there Came all Manner of Choirs:’ Melbourne’s Burgeoning Choral Scene since 1950 * Peter Campbell The great era of the community choral society in Melbourne—as for much of Australia—was probably the fifty years straddling the year 1900, but there is a continuous and frequently vigorous lineage traceable from the earliest years of settlement to the present. District choirs, including the North Melbourne and Collingwood Choral Societies, and the Prahran Philharmonic Society, were established in the period after 1850, during the prosperous gold- rush years,1 when wealth was able to support the cultural pursuits that were the trappings of higher social aspirations. Similar but later organisations include such choirs as the Malvern Choral Union, established in 1907.2 The Melbourne Philharmonic Society, which has been established in 1853, flourished after Bernard Heinze was appointed in 1937,3 especially once the ABC was engaging it for many performances, thus alleviating the Philharmonic of the burden of orchestral and promotional costs. This article examines state of choirs in Melbourne from the time of Heinze’s gradual lessening of duties at the Philharmonic, in the early 1950s, to the present day. Changes in purpose, structure and quantity (both in terms of the number of singers and the number of organisations) are noted, and social and musical reasons for the differences are advanced. A summary of Melbourne’s contemporary choral landscape is presented in order to illustrate the change that has occurred over the period under discussion. The lengthy, productive and intimate relationship between choir, conductor and broadcaster seen in the case of the Philharmonic, Bernard Heinze and the ABC, also exacted a great cost. -

Emily Sun in Recital at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music 6:30 Pm 24 October 2018

Australian Friends of Keshet Eilon present Emily Sun in recital at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music 6:30 pm 24 October 2018 Michaela Kalowski Welcome * Emily Sun & Phillip Shovk Violin Sonata No. 1 in A major Op. 13 Fauré * Emily Sun & Phillip Shovk Violin Sonata FP 119 Poulenc * Emily Sun & Phillip Shovk Concert Fantasy on Themes from Gershwin's PorGy & Bess Op. 19 Frolov * Video Presentation * Michael Gonski & Emily Sun Interview * Jack Ritch Emily Sun is the 2018 ABC Young Performer of the Year and prizewinner in numerous international violin competitions such as the Royal Over-seas League Gold Medal (UK), YampolsKy (Russia), Brahms (Austria) and Lipizer (Italy). Emily has appeared as soloist with Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Tasmania and Queensland Symphony Orchestras, and is a regular guest soloist with orchestras in USA, Europe and Asia. Emily studied at the Sydney Conservatorium with Dr Robin Wilson and is currently at the Royal College of Music, studying with ItzhaK RashKovsKy. She was supported by the Australian Music Foundation Nora Goodridge Award. Phillip Shovk is considered to be one of Australia's foremost concert pianists, chamber musicians, accompanists and pedagogues. After initial lessons with Anatole MirosznyK, he continued his studies with George Humphrey at the Sydney Conservatorium High School from where he graduated with the FranK Hutchens Prize for being the most promising performer of his year. He then furthered his studies at the Moscow State Conservatory, studying with Professor Valery KastelsKy (himself a student of the legendary Heinrich Neuhaus) and graduating as a Master of Fine Arts with highest marKs in all musical subjects. -

THE UNIVERSITY of MELBOURNE ANNUAL REPORT Report of the Proceedings of the University for the Year Ended 31St December, 1949

THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE ANNUAL REPORT Report of the Proceedings of the University for the year ended 31st December, 1949. To His Excellency, Sir Dallas Brooks, K.C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O.,, Governor of Victoria. May it Please Your Excellency, I have the honour, in accordance with Section 43 of the Uni versity Act 1928, to submit to Your Excellency the following report of the Proceedings of the University during 1949. 1. Student Numbers: The first falling off in numbers, since the post-war inflation, took place in 1949 when the total number of students was 9,254 compared with 9,497 in 1948. This was the direct result of the reduction of ex-service entries from 3,770 in 1948 to 3,460 in 1949. The 1950 enrolments are bound to recede sharply and 1951 will probably see the lowest point of the recession in as much as our recent surveys, which are similar to those prepared by the Universities Commission for all Australian Universities, indicate that numbers will start to rise again in 1952. The restrictions on entry remained as in 1948 and applied only to the second year of the Medical Course (42 students who had passed First Year being deferred till 1950) and to the "extra-Victorian quota" in the first year. 2. Staff: The size of the University can be measured to some extent by the number of those on the pay-roll, which increased from 1,344 in 1948 to 1,534 in 1949 (1,186 full-time and 348 part-time). -

Indigenous Encounters in Australian Symphonies of the 1950S

Symphonies of the bush: indigenous encounters in Australian symphonies1 Rhoderick McNeill Dr Rhoderick McNeill is Senior Lecturer in Music History and Music Theory at the University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba. His principal research interest lies in Australian symphonic music of the earlier 20th century, with particular study of Australian symphonies of the 1950s. Between 1985 and 1995 he helped establish the Faculty of Performing Arts at Nommensen University in Medan, Indonesia. Dr McNeill’s two volume Indonesian-language textbook on Music History was published in Jakarta in 1998 and has been reprinted twice. Landscape was a powerful stimulus to many composers working within extended tonal, nationalist idioms in the early 20th century. Sibelius demonstrated this trend in connection with Finland, its landscape, literature, history and myths. Similar cases can be made for British composers like Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Bax and Moeran, and for American composers Copland and Harris. All these composers wrote symphonies and tone poems, and were important figures in the revival of these forms during the 1920s and 30s. Their music formed much of the core of „modern‟ repertoire heard in Australian orchestral concerts prior to 1950. It seemed logical for some Australian composers -by no means all - to seek a home-grown style which would parallel national styles already forged in Finland, Britain and the United States. They believed that depicting the „timeless‟ Australian landscape in their music would introduce this new national style; their feelings on this issue are clearly outlined in the prefaces to their scores or in their writings or by giving their works evocative Australian titles. -

Publications for Jeanell Carrigan 2021 2020 2019

Publications for Jeanell Carrigan 2021 Carrigan, J., Caillouet, J. (2021). Innovation. In Anna Reid, Carrigan, J. (2020). The Composers' Series: Volume 8 (a) - Neal Peres Da Costa, Jeanell Carrigan (Eds.), Creative Piano Solos Advanced - Frank Hutchens [Portfolio]. The Research in Music: Informed Practice, Innovation and Composers' Series: Volume 8 (a) - Piano Solos Advanced - Transcendence, (pp. 95-99). New York, USA: Routledge. <a Frank Hutchens, (pp. vi - 103). Wollongong, Australia: href="http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780429278426-10">[More Wirripang Pty Ltd. Information]</a> Carrigan, J. (2020). The Composers' Series: Volume 8 (b) - 2020 Piano Solos Intermediate - Frank Hutchens [Portfolio]. The Composers' Series: Volume 8 (b) - Piano Solos Intermediate - Carrigan, J. (2020). Sea Impressions: Piano Miniatures by Frank Hutchens, (pp. vi - 71). Wollongong, Australia: Australian Composers, Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang Pty Wirripang Pty Ltd. Ltd. Carrigan, J. (2020). The Composers' Series: Volume 9 Piano Carrigan, J. (2020). Reverie: Piano Music by Australian Solos - Lindley Evans [Portfolio]. The Composers' Series: Women, CD, Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang. Volume 9 Piano Solos - Lindley Evans, (pp. 1 - 81). Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang. Carrigan, J., Choe, M. (2020). [1-3] Sonata for Cello and Piano: Allegro ritmico; Lento; Allegro [5-8] Four Aspects: Grieving; 2019 Stress; Hope; Healing [10] An Evening Stroll [11] The Lake [12] Nocturne for Piano Carrigan, J. (2019). Meta Overman: Sonata for Viola and [Portfolio]. On In Tribute: Music by Dulcie Holland, CD, Piano, (pp. 1 - 28). Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang Pty Ltd. Wollongong, Australia: Wirripang Media Pty Ltd. Carrigan, J. (2019). 1. Scherzo No. 1 in B minor, 3. Through Richter, G., Carrigan, J., Choe, M. -

INSIDE: * Changing Australia * Lousy Teachers...And All That * The

INSIDE: * Changing Australia * Lousy Teachers.....and All That * The Reader Writes * Trip to Lesotho Volume 7 Num ber 54 June 1970 THIS CHANGING AUSTRALIA The following excerpts are from an Occasional Address CONTENTS given at the April 2 Graduation Ceremony by Professor S. McCulloch, of the University of California. who has been visiting the Monash Department of History : This Changing Australia After being away from Australia for fifteer Lousy Teachers And All That 8 years, with the exception of a flying visit in 1964, I see enormous changes. In 1954-55, I SpE What the Reader is Writing 1 1 nine months in Sydney, and observed Australia gc ing economic and social momentum after adjustin~ A Trip to Lesotho 17 to the aftermath of World War II. In 1970, Ilm amazed at the progress that has been made. Dis Monash to Stage A.U.L.L.A. Congress 20 regarding the obvious changes, such as the new buildings, the swarming cars driven by a pe op l e w Radio Interview by New Zealand are obviously betting maniacs (I bet IIII just Broadcasting Corporation 22 miss him or her), and the enormously efficient air service, I would like to concentrate on fiVE Information, Please! 24 areas - immigration, industry, agriculture, edu cation, and the arts and culture generally. Obituary - Mr. N.J. Field 25 What has changed Australia the most to one Concert for Hall Appeal 26 who was born here, but been away for a very lon~ time, is the flood of immigrants who have reachE Lunch-Hour Concert Series 27 these shores since the war. -

75Th ANNIVERSARY 2020

75th ANNIVERSARY 2020 What better time is there to note the history of one of Lane Cove’s icons than a 75th Anniversary? 2020 marks that celebratory year for Lane Cove Music. On 26th March 1946 Reverend Louis Blanchard, Minister of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church Longueville, was inspired to call a meeting to form a music club with the object of providing first class classical and semi-classical music and entertainment for church members and friends. Initial meetings were held at the Manse, the Vestry and the Church Hall. The idea was so well received that a group was formed as an organisation of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church Longueville and named the “Longueville-Northwood Music Club” with a constitution being drawn up and adopted on 22nd May 1946. Until the end of 1959 concerts were held in the Masonic Hall at 231 Longueville Road, now the Shinnyo Australia Buddhist Temple. Rev. Louis Blanchard 1973 The current name Lane Cove Music dates from 2007, the abbreviated version being in step with the trend set by other music clubs, omission of ‘club’ being deemed to sound less exclusive at a time when all clubs were seeking a membership boost. For expediency the capitals ‘LCM’ or words ‘the club’ will be used henceforth in this text. At that initial meeting in March 1946 it was agreed there would be five concerts held in the first year – subscriptions to be one guinea, being one pound one shilling (£1/1- in pre 1966 currency) with a fee of four shillings for visitors. By the third meeting the Executive Committee had been elected with Rev. -

F Te Hititomts of Iulbonrnt 1939

f te Hititomts of iUlbonrnt 1939. VISITOR. HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR OF VICTORIA. COUNCIL. CHANCELLOR SIR JAMES WILLIAM BARRETT, K.B.E., C.B., C.M.G., LL.D. (Manitoba), M.D., M.S. (Melb.), F.R.A.C.S., F.R.C.S. (Eng.), C.M.Z.S. Elected 30th August, 1935. DEPUTY-CHANCELLOR. RT. HON. SIR JOHN GREIG LATHAM, P.C, G.C.M.G., K.C., M.A., LL.M. Elected 30th August, 1935. VICE-CHAN CELLOR. JOHN DUDLEY GIBBS MEDLEY, M.A. (Oxon). MEMBERS. Appointed by the Governor-in-Council, 17th December, 1935— HON. JOHN PERCY JONES, M.L.C. Originally appointed 11th July, 1923. HON. SIR STANLEY SEYMOUR ARGYLE, K.B.E., M.L.A., M.B.. B.S. Originally appointed 15th September, 1927. SIR WILLIAM LENNON RAWS, KT.B., C.B.E. Originally appointed 12th December, 1928. HON. JOHN LEMMON, M.L.A. Originally appointed, 19th July, 1932. CHARLES HAROLD PETERS, M.C. Originally appointed Sth December, 1932. JAMES MACDOUGALL, Originally appointed Uih August, 1933. HON. PERCY JAMES CLAREY, M.L.C. 19th December, 1938— JOSEPH EDWIN DON. Elected by Convocation, 17th December, 1935— MR. JUSTICE CHARLES JOHN LOWE, M.A., LL.B. Originally elected 10th February, 1927. JAMES RALPH DARLING, M.A. (Oxon and Melb,). Originally elected 31st October, 1933. MORRIS MONDLE PHILLIPS, M.A. Originally elected 13th November, 1934. BERNARD TRAUGOTT ZWAR, M.D., M.S., F.R.A.C.S. Originally elected 7th May, 1935. WILFRF.D RUSSELL GRIMWADE, C.B.E., B.Sc. Originally elected 13th August, 1935. Elected by Convocation, 16th December, 1937— SIR JAMES WILLIAM BARRETT, K.B.E. -

Concertos Ddd Concertos for Piano & Strings for Piano & Strings GORDON JACOB Piano Concerto No

SOMMCD 254 CONCERTOS DDD CONCERTOS for Piano & Strings for Piano & Strings GORDON JACOB Piano Concerto No. 1 (premiere recording) MALCOLM WILLIAMSON Piano Concerto No. 2 DOREEN CARWITHEN Piano Concerto GORDON JACOB Mark Bebbington piano (premiere recording) Innovation Chamber Ensemble (players from the CBSO) Richard Jenkinson conductor DOREEN CARWITHEN Gordon Jacob: Piano Concerto No. 1 (17:08) Doreen Carwithen: Piano Concerto (33:28) MALCOLM WILLIAMSON 1 I. Allegro assai 4:26 7 I. Allegro assai 12:43 2 II. Adagio 5:29 8 II. Lento 10:08 3 III. Allegro risoluto 7:12 9 III. Moderato e deciso ma con moto 10:36 Malcolm Williamson: Piano Concerto No. 2 (16:26) Mark Bebbington Total Duration: 67:20 4 I. Allegro con brio 4:31 piano 5 II. Andante lento 7:35 6 III. Allegro con spirito 4:19 Innovation Chamber Ensemble Recording Producer: Siva Oke Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor (players from the CBSO) Recording location: CBSO Centre, Birmingham, 2-3 June 2014 Front Cover: Mark Bebbington. Photo © Rama Knight Richard Jenkinson Design and Layout: Andrew Giles conductor © & 2014 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU of attractive and technically accomplished music but also as an expert on Concertos for Piano and Strings orchestration. Composers as diverse as Vaughan Williams and Noël Coward by entrusted him with arrangements of their music, and his rousing version of the national anthem was one of the musical highlights of the 1953 coronation. Gordon Jacob . Malcolm Williamson . Doreen Carwithen Jacob’s Concerto No. 1 for piano and string orchestra, which is here receiving its first commercial recording, was written in 1927 and premièred by its dedicatee, GORDON JACOB (1895-1984) fellow composer Arthur Benjamin, with the Queen’s Hall Orchestra under Concerto No. -

The Impact of Russian Music in England 1893-1929

THE IMPACT OF RUSSIAN MUSIC IN ENGLAND 1893-1929 by GARETH JAMES THOMAS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham March 2005 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is an investigation into the reception of Russian music in England for the period 1893-1929 and the influence it had on English composers. Part I deals with the critical reception of Russian music in England in the cultural and political context of the period from the year of Tchaikovsky’s last successful visit to London in 1893 to the last season of Diaghilev’s Ballet russes in 1929. The broad theme examines how Russian music presented a challenge to the accepted aesthetic norms of the day and how this, combined with the contextual perceptions of Russia and Russian people, problematized the reception of Russian music, the result of which still informs some of our attitudes towards Russian composers today. Part II examines the influence that Russian music had on British composers of the period, specifically Stanford, Bantock, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Frank Bridge, Bax, Bliss and Walton. -

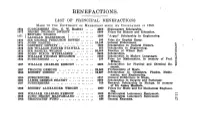

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND .