Terminal Lakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flow Regime Change in an Endorheic Basin in Southern Ethiopia

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 18, 3837–3853, 2014 www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/18/3837/2014/ doi:10.5194/hess-18-3837-2014 © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Flow regime change in an endorheic basin in southern Ethiopia F. F. Worku1,4,5, M. Werner1,2, N. Wright1,3,5, P. van der Zaag1,5, and S. S. Demissie6 1UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, P.O. Box 3015, 2601 DA Delft, the Netherlands 2Deltares, P.O. Box 177, 2600 MH Delft, the Netherlands 3University of Leeds, School of Civil Engineering, Leeds, UK 4Arba Minch University, Institute of Technology, P.O. Box 21, Arba Minch, Ethiopia 5Department of Water Resources, Delft University of Technology, P.O. Box 5048, 2600 GA Delft, the Netherlands 6Ethiopian Institute of Water Resources, Addis Ababa University, P.O. Box 150461, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Correspondence to: F. F. Worku ([email protected]) Received: 29 December 2013 – Published in Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.: 29 January 2014 Revised: – – Accepted: 20 August 2014 – Published: 30 September 2014 Abstract. Endorheic basins, often found in semi-arid and 1 Introduction arid climates, are particularly sensitive to variation in fluxes such as precipitation, evaporation and runoff, resulting in Understanding the hydrology of a river and its historical flow variability of river flows as well as of water levels in end- characteristics is essential for water resources planning, de- point lakes that are often present. In this paper we apply veloping ecosystem services, and carrying out environmen- the indicators of hydrological alteration (IHA) to characterise tal flow assessments. -

Benchmark 3: Evaluation of Alternatives with Respect to Existing Conditions August 2015

Salton Sea Funding and Feasibility Action Plan Benchmark 3: Evaluation of Alternatives With Respect to Existing Conditions August 2015 Prepared by: Prepared for: This document is prepared as a living document for public review and comment. Comments may be provided to: Salton Sea Authority 82995 Hwy 111, Suite 200 Indio, CA 92201 Email: [email protected] Comments will be reviewed and incorporated as appropriate. If substantive comments are received, a revised document may be produced and distributed. Preferred citation: Salton Sea Authority (2015). Salton Sea Funding and Feasibility Action Plan Benchmark 3 Report: Evaluation of Alternatives With Respect to Existing Conditions, August Report. Revision Record Revisions to this document will be reviewed and approved through the same level of authority as the original document. All changes to the Benchmark 3 Report must be authorized by the Principal in Charge. Date Version Changes January Working Posted on Salton Sea Authority website. 2015 Draft Included changes from draft review by Salton Sea TCT. June 2015 First Updated hydrology section and inflow Complete projections including Figures 48-52, along with Document editorial revisions. August Revision 1 Added this Revision Record. Corrected title of 2015 California Department of Fish and Wildlife and other minor editorial revisions. Updated discussion of historical flows from 2003-present. Tetra Tech, Inc. i August 2015 Executive Summary This report presents a review of Salton Sea restoration alternatives and their components and determine how well they would perform under current and future inflows. Alternatives are considered with respect to existing hydrologic conditions at the Sea, as of 2014, and projected future hydrology. -

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems Around the World

Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Prepared for: State of Utah Great Salt Lake Advisory Council Prepared by: AECOM February 15, 2019 Consequences of Drying Lake Systems around the World Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 13 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................. 13 III. APPROACH ............................................................................. 16 IV. CASE STUDIES OF DRYING LAKE SYSTEMS ...................... 17 1. LAKE URMIA ..................................................................................................... 17 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 18 b) Economic Consequences ............................................................................... 19 c) Social Consequences ..................................................................................... 20 d) Environmental Consequences ........................................................................ 21 e) Relevance to Great Salt Lake ......................................................................... 21 2. ARAL SEA ........................................................................................................ 22 a) Overview of Lake Characteristics .................................................................... 22 b) Economic -

Hydrographic Development of the Aral Sea During the Last 2000 Years Based on a Quantitative Analysis of Dinoflagellate Cysts

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 234 (2006) 304–327 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Hydrographic development of the Aral Sea during the last 2000 years based on a quantitative analysis of dinoflagellate cysts P. Sorrel a,b,*, S.-M. Popescu b, M.J. Head c,1, J.P. Suc b, S. Klotz b,d, H. Oberha¨nsli a a GeoForschungsZentrum, Telegraphenberg, D-14473 Potsdam, Germany b Laboratoire Pale´oEnvironnements et Pale´obioSphe`re (UMR CNRS 5125), Universite´ Claude Bernard—Lyon 1, 27-43, boulevard du 11 Novembre, 69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France c Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Downing Place, Cambridge CB2 3EN, UK d Institut fu¨r Geowissenschaften, Universita¨t Tu¨bingen, Sigwartstrasse 10, 72070 Tu¨bingen, Germany Received 30 June 2005; received in revised form 4 October 2005; accepted 13 October 2005 Abstract The Aral Sea Basin is a critical area for studying the influence of climate and anthropogenic impact on the development of hydrographic conditions in an endorheic basin. We present organic-walled dinoflagellate cyst analyses with a sampling resolution of 15 to 20 years from a core retrieved at Chernyshov Bay in the NW Large Aral Sea (Kazakhstan). Cysts are present throughout, but species richness is low (seven taxa). The dominant morphotypes are Lingulodinium machaerophorum with varied process length and Impagidinium caspienense, a species recently described from the Caspian Sea. Subordinate species are Caspidinium rugosum, Romanodinium areolatum, Spiniferites cruciformis, cysts of Pentapharsodinium dalei, and round brownish protoper- idiniacean cysts. The chlorococcalean algae Botryococcus and Pediastrum are taken to represent freshwater inflow into the Aral Sea. The data are used to reconstruct salinity as expressed in lake level changes during the past 2000 years. -

Lled Basins of the Red

Deep-Sea Research I 46 (1999) 1779}1792 Hydrographic changes during 20 years in the brine-"lled basins of the Red Sea Pierre Anschutz! *,GeH rard Blanc!, Fabienne Chatin", Magali Geiller", Marie-Claire Pierret" !De& partement de Ge& ologie et Oce&anographie (D.G.O.), Universite& Bordeaux 1, CNRS UMR 5805, 33405 Talence Cedex, France "Centre de Ge& ochimie de la Surface, Institut de Ge&ologie, Universite& Louis Pasteur, CNRS UMR 7517, 67084, Strasbourg, France Received 16 June 1998; accepted 8 February 1999 Abstract Many of the deep basins "lled by hot brines in the Red Sea have not been investigated since their discovery in the early 1970s. Twenty years later, in September 1992, six of these deeps were revisited. The temperature and salinity of the Suakin, Port Sudan, Chain B, and Nereus deeps ranged from 23.25 to 44.603C and from 144 to 270&. These values were approximately the same in 1972, indicating that the budget of heat and salt was quite balanced. We measured strong gradients of properties in the transition zone between brines and overlying seawater. The contribution of salinity to the density gradient was more than one order of magnitude higher than the opposite contribution of temperature across the seawater}brine interface. Therefore the interface was extemely stable, and the transfer of properties across it was considered to be controlled mostly by molecular di!usion. We calculate that the di!usional transport of salt from the brines to seawater cannot a!ect signi"cantly the salinity of the brines over a 20 year period, which agrees with the observations. -

Ocean Storage

277 6 Ocean storage Coordinating Lead Authors Ken Caldeira (United States), Makoto Akai (Japan) Lead Authors Peter Brewer (United States), Baixin Chen (China), Peter Haugan (Norway), Toru Iwama (Japan), Paul Johnston (United Kingdom), Haroon Kheshgi (United States), Qingquan Li (China), Takashi Ohsumi (Japan), Hans Pörtner (Germany), Chris Sabine (United States), Yoshihisa Shirayama (Japan), Jolyon Thomson (United Kingdom) Contributing Authors Jim Barry (United States), Lara Hansen (United States) Review Editors Brad De Young (Canada), Fortunat Joos (Switzerland) 278 IPCC Special Report on Carbon dioxide Capture and Storage Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 279 6.7 Environmental impacts, risks, and risk management 298 6.1 Introduction and background 279 6.7.1 Introduction to biological impacts and risk 298 6.1.1 Intentional storage of CO2 in the ocean 279 6.7.2 Physiological effects of CO2 301 6.1.2 Relevant background in physical and chemical 6.7.3 From physiological mechanisms to ecosystems 305 oceanography 281 6.7.4 Biological consequences for water column release scenarios 306 6.2 Approaches to release CO2 into the ocean 282 6.7.5 Biological consequences associated with CO2 6.2.1 Approaches to releasing CO2 that has been captured, lakes 307 compressed, and transported into the ocean 282 6.7.6 Contaminants in CO2 streams 307 6.2.2 CO2 storage by dissolution of carbonate minerals 290 6.7.7 Risk management 307 6.2.3 Other ocean storage approaches 291 6.7.8 Social aspects; public and stakeholder perception 307 6.3 Capacity and fractions retained -

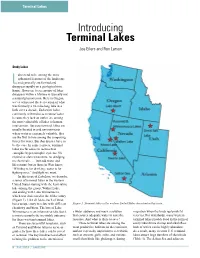

Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson

Terminal Lakes Introducing Terminal Lakes Joe Eilers and Ron Larson Study Lakes akes tend to be among the more ephemeral features of the landscape Land generally are formed and disappear rapidly on a geological time frame. However, to see groups of lakes disappear within a lifetime is typically not a natural phenomenon. Here in Oregon, we’ve witnessed the desiccation of what was formerly a 16-mile-long lake in a little over a decade. Endorehic lakes, commonly referred to as terminal lakes because they lack an outlet, are among the most vulnerable of lakes to human intervention. Because terminal lakes are usually located in arid environments where water is extremely valuable, they are the first to lose among the competing forces for water. But that doesn’t have to be the case. In some respects, terminal lakes are far easier to restore than eutrophic/hypereutrophic systems. No expensive alum treatments, no dredging, no chemicals . just add water and life returns: but as those in West know, “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.” And fight we must. In this issue of LakeLine, we describe a series of terminal lakes in the western United States starting with the least saline lake among the group, Walker Lake, and ending with Lake Winnemucca, which was desiccated in the 20th century (Figure 1). Like all lakes, each of these has a unique story to relate with different Figure 1. Terminal lakes in the western United States described in this issue. chemistry and biota. The loss of Lake Winnemucca is an informative tale, but it a wider audience and reach a solution migration when the birds replenish fat is not necessarily the inevitable outcome that ensures adequate water to save the reserves. -

Nutrient Dynamics in the Jordan River and Great

NUTRIENT DYNAMICS IN THE JORDAN RIVER AND GREAT SALT LAKE WETLANDS by Shaikha Binte Abedin A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering The University of Utah August 2016 Copyright © Shaikha Binte Abedin 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Shaikha Binte Abedin has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Ramesh K. Goel , Chair 03/08/2016 Date Approved Michael E. Barber , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved Steven J. Burian , Member 03/08/2016 Date Approved and by Michael E. Barber , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In an era of growing urbanization, anthropological changes like hydraulic modification and industrial pollutant discharge have caused a variety of ailments to urban rivers, which include organic matter and nutrient enrichment, loss of biodiversity, and chronically low dissolved oxygen concentrations. Utah’s Jordan River is no exception, with nitrogen contamination, persistently low oxygen concentration and high organic matter being among the major current issues. The purpose of this research was to look into the nitrogen and oxygen dynamics at selected sites along the Jordan River and wetlands associated with Great Salt Lake (GSL). To demonstrate these dynamics, sediment oxygen demand (SOD) and nutrient flux experiments were conducted twice through the summer, 2015. The SOD ranged from 2.4 to 2.9 g-DO m-2 day-1 in Jordan River sediments, whereas at wetland sites, the SOD was as high as 11.8 g-DO m-2 day-1. -

Okeanos Explorer Rov Dive Summary

OKEANOS EXPLORER ROV DIVE SUMMARY Site Name GB907 Expedition Kelley Elliott/ Coordinator/ Brian Bingham ROV Lead Stephanie Farrington (Biology) Science Team Leads Jamie Austin (Geology) General Area Gulf of Mexico Descriptor Cruise Season Leg Dive Number ROV Dive Name EX1402 3 DIVE02 ROV: Deep Discoverer Equipment Deployed Camera Platform: Seirios CTD Depth Altitude Scanning Sonar USBL Position Heading ROV Measurements Pitch Roll HD Camera 1 HD Camera 2 Low Res Cam 1 Low Res Cam 2 Low Res Cam 3 Low Res Cam 4 Low Res Cam 2 Equipment N/A Malfunctions Dive Summary: EX1402L3_DIVE02 ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ In Water at: 2014-04-13T13:45:38.439000 27°, 05.899' N ; 092°, 37.310' W Out Water at: 2014-04-13T19:12:34.841000 27°, 05.096' N ; 092°, 36.588' W ROV Dive Summary Off Bottom at: 2014-04-13T18:24:04.035000 (From processed ROV 27°, 05.455' N ; 092°, 36.956' W data) On Bottom at: 2014-04-13T14:31:16.507000 27°, 05.519' N ; 092°, 37.099' W Dive duration: 5:26:56 Bottom Time: 3:52:47 Max. depth: 1266.7 m Special Notes Primary Jamie Austin, EX, UT Austin, [email protected] Stephanie Farrington, EX, HBOI/FAU, [email protected] Andrea Quattrini, Temple, Temple, [email protected] Scientists Involved Bernie Ball, Duke, Duke, [email protected] (please provide name / Brian Kinlan, NOAA NMFS, [email protected] location / affiliation / email) Carolyn Ruppel, Woods Hole, USGS, [email protected] Erik Cordes, Temple, Temple, [email protected] Larry Mayer, UNH, UNH CCOM, [email protected] Michael Vecchione, -

International Geography Exam Part 2

2018 International Geography Bee 7. Which of these Washington cities is driest due to rain International Geography Exam - Part 2 shadow? A. Seattle B. Tacoma Instructions – This portion of the IGB Exam consists of C. Bellingham 100 questions. You will receive two points for a correct D. Spokane answer. You will lose one point for an incorrect answer. Blank responses lose no points. Please fill in the bubbles 8. The Karakum Desert in Central Asia is bordered by completely on the answer sheet. You may write on the what two mountain ranges? examination, but all responses must be bubbled on the A. Ural and Atlas answer sheet. Diacritic marks such as accents have been B. Caucasus and Hindu Kush omitted from place names and other proper nouns. You C. Hindu Kush and Yin have one hour to complete this set of multiple choice D. Caucasus and Ural questions. 9. All of these contain parts of the Kalahari Desert 1. Which of these best defines the term intergovernmental EXCEPT which of the following? organization? A. South Africa A. a multinational corporation B. Kenya B. a treaty with multiple nations as signatories C. Namibia C. an organization composed of sovereign states D. Botswana established by a charter or treaty D. an international aid agency 10. All of these border the Red Sea’s western shore EXCEPT which of the following? 2. Which of the following is an example of an A. Saudi Arabia intergovernmental organization? B. Egypt A. the United Nations C. Djibouti B. the International Red Cross D. Sudan C. the Quartet D. -

A Phytoremediation Pilot Project at the LCP Chemicals

Case Study LCP Chemicals Site Phytoremediation Pilot Project Shea Jones Remedial Project Manager EPA Region 4 Outline of Presentation z Background Information z Groundwater Quality z Groundwater Seeps z Project Goal z Implementation of Project z Community and Agency Concerns z Current Status z Next Steps z Lessons Learned Background Information z 550-acre site z Former oil refinery, paint manufacturing co., power plant, and chlor-alkali facility operated from 1919- 1994 z Significant PRP-led removal actions in 1999 ($60 million) z Soil and sediment contaminated with lead, mercury, and PCBs z Fish advisories z Currently in RI/FS phase Groundwater Quality z Multiple rounds of horizontal and vertical well data z Hg levels as high as 330 ppb and Pb as high as 120 ppb z Hg found below a sandstone layer z Caustic Brine Pool below old cell buildings z Removal Action Groundwater Seeps z During conditions of high water table, seepage of groundwater occurs along portions of the shoreline that separates the upland soils from the tidal marsh z Dark brown color z Some COCs present at elevated levels (74 ppb Hg and 60 ppb Pb) Project Goal z To locally suppress the groundwater table (0.9 ft) and therefore, prevent the seeps from recontaminating the marsh z Secondary Goals – Create a root zone that will degrade organic contaminants through microbial degradation – Stabilize metals and take them up (lower mobility and availability) z Insert first scanned picture showing seep location z Insert scanned pics showing conceptual site model Plant Selection z List of potentially applicable plants was examined z List narrowed based on tolerance to site conditions (i.e. -

Algae Flora of Graduation Towers in the Town of Ciechocinek

Ecological Questions 14/2011: 25 – 29 DOI: 10.2478/v10090-011-0007-6 Algae flora of graduation towers in the town of Ciechocinek Marta Luścińska, Malwina Gadziemska Department of Plant Ecology and Nature Protection Nicolaus Copernicus University, Gagarina 9, 87–100 Toruń e-mail: [email protected] Summary. The research was focused on algae occurring on wooden constructions of three graduation towers, which are the main ele- ments of historical salt production technology, located in the health-resort of Ciechocinek in the region of Kujawy. The research also included algae occurring in reservoirs with brine condensed on graduation towers, as well as algae from puddles and the soil under the graduation towers. 52 algae taxa were recorded in the collected material. Representatives of the following phyla were distinguished: 5 taxa of Cyanoprokaryota, 46 taxa of Heterokontophyta (including 44 taxa of diatoms) and 7 taxa of Chlorophyta. Samples from the sites with brine of the lowest salt concentration (4%) turned out to be the most abundant in species. Key words: halophylic algae, diatoms Chlorophyta, Dunalulla, brine, saline soils. 1. Introduction ers no. 1 and 3 (Fig. 1). She reported the occurrence of 44 algae species, mainly diatoms. All the aforementioned studies focused on algae in- The occurrence of algae in the environment with extreme habiting puddles and small water bodies with different de- salinity, such as gradually thickened brine flowing down grees of salinity, located within salt marshes. Whereas the the graduation towers in Ciechocinek, evoked interest present paper aims at investigating the algae flora occur- among researchers already since the end of the 19th cen- ring on construction elements of the graduation towers, as tury.