Children on Medication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abdominal Epilepsy in an Adult: a Diagnosis Often Missed Psychiatry Section

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19873.8600 Case Report Abdominal Epilepsy in an Adult: A Diagnosis Often Missed Psychiatry Section DEVAVRAT G HARSHE1, SNEHA D HARSHE2, GURUDAS R HARSHE3, GAYATRI G HARSHE4 ABSTRACT Abdominal Epilepsy (AE) is a variant of temporal lobe epilepsy and is commonly seen in pediatric age group. There are however, multiple reports of abdominal epilepsy in adolescents and even in adults. Chronic and recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms with one or more neuropsychiatric manifestations are often the presenting picture for a patient with AE. Such patients therefore, are more likely to consult a general practioner, a physician, a surgeon or a gastroenterologist than consulting a psychiatrist or a neurologist. We hereby present such a case of AE in an adult with review of similar reports. Keywords: Abdominal pain, Consultation liaison psychiatry, Temporal lobe CASE REPORT persisted. Considering the episodic hypertension with headache, A 45-year-old female with no past significant medical or psychiatric pheochromocytoma was suspected and was ruled out, when 24 history was referred to a psychiatric nursing home by a surgeon hours urinary Vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and serum metanephrines for suspected psychogenic abdominal pain. History consisted of turned out to be normal. Abdominal migraine and porphyria were multiple clustered episodes of abdominal pain since one year; each ruled out considering the duration of episodes, lack of any family episode consisting of insufferable abdominal pain with genuine history and absence of other findings supportive of porphyria. distress. Pain would begin at the right iliac fossa and radiate to Abdominal epilepsy was then considered as the diagnosis and was the umbilical area. -

Ictus Emeticus: Case Reports and Literature Review Ismail A

Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences (PJNS) Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 4 7-2007 Ictus Emeticus: Case Reports and Literature Review Ismail A. Khatri Shifa International Hospital Umar S. Chaudhry Shifa International Hospital Abdul Majeed Khatri Neurology Center, Nacogdoches, Texas, USA Zahid F. Cheema University of Oklahoma Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pjns Part of the Neurology Commons Recommended Citation Khatri, Ismail A.; Chaudhry, Umar S.; Khatri, Abdul Majeed; and Cheema, Zahid F. (2007) "Ictus Emeticus: Case Reports and Literature Review," Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences (PJNS): Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pjns/vol2/iss2/4 C A S E R E P O R T ICTUS EMETICUS: CASE REPORTS AND LITERATURE REVIEW Ismail A. Khatri1, Umar S. Chaudhry1, Abdul Majeed Khatri2, Zahid F. Cheema3 1Department of Neurology, Shifa International Hospital, Islamabad, Pakistan; 2 Neurology Center, Nacogdoches, Texas, USA; 3Department of Neurology, University of Oklahoma Medical Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA Correspondence to: Dr. Khatri, Section of Neurology, Shifa International Hospitals Ltd., Pitras Bukhari Road, Sector H-8/4, Islamabad 46000, Pakistan. Tel: (92-51) 444-6801-30 Ext: 3175, 3025. Fax: (92-51) 486-3182. Email: [email protected] Pak J Neurol Sci 2007; 2(2):96-98 ABSTRACT The diagnosis of abdominal epilepsy came into vogue in the 1950s and 1960s. Vomiting as a manifestation of seizure has been given different names including ictus emeticus. We report three cases of this interesting albeit uncommon condition. It is important for physicians to familiarize themselves with this symptomatology so as not to overlook this unique presentation of epileptic seizures. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 697 CG 021 192 AUTHOR Gougelet, Robert M.; Nelson, E. Don TITLE Alcohol and Other Chemicals. Adolescent A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 697 CG 021 192 AUTHOR Gougelet, Robert M.; Nelson, E. Don TITLE Alcohol and Other Chemicals. Adolescent Alcoholism: Recognizing, Intervening, and Treating Series No. 6. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Dept. of Family Medicine. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Rockville, MD. Bureau of Health Professions. PUB DATE 87 CONTRACT 240-83-0094 NOTE 30p.; For other guides in this series, see CG 021 187-193. AVAILABLE FROMDepartment of Family Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210 ($5.00 each, set of seven, $25.00; audiocassette of series, $15.00; set of four videotapes keyed to guides, $165.00 half-inch tape, $225.00 three-quarter inch tape; all orders prepaid). PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) -- Reports - General (140) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Plstage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; *Alcoholism; *Clinical Diagnosis; *Drug Use; *Family Problems; Physician Patient Relationship; *Physicians; Substance Abuse; Units of Study ABSTRACT This document is one of seven publications contained in a series of materials for physicians on recognizing, intervening with, and treating adolescent alcoholism. The materials in this unit of study are designed to help the physician know the different classes of drugs, recognize common presenting symptoms of drug overdose, and place use and abuse in context. To do this, drug characteristics and pathophysiological and psychological effects of drugs are examined as they relate to administration, -

Dictionary of Epilepsy

DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY PART I: DEFINITIONS .· DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY PART I: DEFINITIONS PROFESSOR H. GASTAUT President, University of Aix-Marseilles, France in collaboration with an international group of experts ~ WORLD HEALTH- ORGANIZATION GENEVA 1973 ©World Health Organization 1973 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accord ance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. For rights of reproduction or translation of WHO publications, in part or in toto, application should be made to the Office of Publications and Translation, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. The World Health Organization welcomes such applications. PRINTED IN SWITZERLAND WHO WORKING GROUP ON THE DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY1 Professor R. J. Broughton, Montreal Neurological Institute, Canada Professor H. Collomb, Neuropsychiatric Clinic, University of Dakar, Senegal Professor H. Gastaut, Dean, Joint Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Aix-Marseilles, France Professor G. Glaser, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., USA Professor M. Gozzano, Director, Neuropsychiatric Clinic, Rome, Italy Dr A. M. Lorentz de Haas, Epilepsy Centre "Meer en Bosch", Heemstede, Netherlands Professor P. Juhasz, Rector, University of Medical Science, Debrecen, Hungary Professor A. Jus, Chairman, Psychiatric Department, Academy of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland Professor A. Kreindler, Institute of Neurology, Academy of the People's Republic of Romania, Bucharest, Romania Dr J. Kugler, Department of Psychiatry, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Dr H. Landolt, Medical Director, Swiss Institute for Epileptics, Zurich, Switzerland Dr B. A. Lebedev, Chief, Mental Health, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland Dr R. L. Masland, Department of Neurology, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, USA Professor F. -

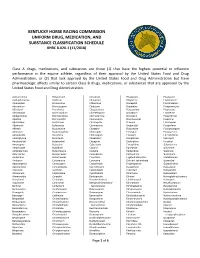

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

Phenobarbital Sodium Injection West-Ward Pharmaceuticals Corp

PHENOBARBITAL SODIUM- phenobarbital sodium injection West-Ward Pharmaceuticals Corp. Disclaimer: This drug has not been found by FDA to be safe and effective, and this labeling has not been approved by FDA. For further information about unapproved drugs, click here. ---------- Phenobarbital Sodium Injection, USP CIV FOR IM OR SLOW IV ADMINISTRATION DO NOT USE IF SOLUTION IS DISCOLORED OR CONTAINS A PRECIPITATE Rx only DESCRIPTION The barbiturates are nonselective central nervous system (CNS) depressants which are primarily used as sedative hypnotics and also anticonvulsants in subhypnotic doses. The barbiturates and their sodium salts are subject to control under the Federal Controlled Substances Act (CIV). Barbiturates are substituted pyrimidine derivatives in which the basic structure common to these drugs is barbituric acid, a substance which has no central nervous system activity. CNS activity is obtained by substituting alkyl, alkenyl or aryl groups on the pyrimidine ring. Phenobarbital Sodium Injection, USP is a sterile solution for intramuscular or slow intravenous administration as a long-acting barbiturate. Each mL contains phenobarbital sodium either 65 mg or 130 mg, alcohol 0.1 mL, propylene glycol 0.678 mL and benzyl alcohol 0.015 mL in Water for Injection; hydrochloric acid added, if needed, for pH adjustment. The pH range is 9.2-10.2. Chemically, phenobarbital sodium is 2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-Pyrimidinetrione,5-ethyl-5-phenyl-, monosodium salt and has the following structural formula: C12H11N2NaO3 MW 254.22 The sodium salt of phenobarbital occurs as a white, slightly bitter powder, crystalline granules or flaky crystals; it is soluble in alcohol and practically insoluble in ether or chloroform. -

A Rare Cause of Unexplained Abdominal Pain

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.10120 Abdominal Epilepsy: A Rare Cause of Unexplained Abdominal Pain Anvesh Balabhadra 1 , Apoorva Malipeddi 2 , Niloufer Ali 3 , Raju Balabhadra 4 1. Department of Neurology, Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Hyderabad, IND 2. Department of Internal Medicine, Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Hyderabad, IND 3. Department of Neurology, Aster Prime Hospital, Hyderabad, IND 4. Department of Neurological Surgery, Aster Prime Hospital, Hyderabad, IND Corresponding author: Anvesh Balabhadra, [email protected] Abstract Abdominal epilepsy (AE) is a very rare diagnosis; it is considered to be a category of temporal lobe epilepsies and is more commonly a diagnosis of exclusion. Demographic presentation of AE is usually in the pediatric age group. However, there is recorded documentation of its occurrence even in adults. AE can present with unexplained, relentless, and recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms such as paroxysmal pain, nausea, bloating, and diarrhoea that improve with antiepileptic therapy. It is commonly linked with electroencephalography (EEG) changes in the temporal lobes along with symptoms that reflect the involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) such as altered consciousness, confusion, and lethargy. Due to the vague nature of these symptoms, there is a high chance of misdiagnosing a patient. We present the case of a 20-year-old man with AE who was misdiagnosed with psychogenic abdominal pain after undergoing multiple investigations with various hospital departments. Categories: Neurology, Gastroenterology, General Surgery Keywords: eeg, abdominal epilepsy, temporal lobe epilepsy, unexplained abdominal pain Introduction Abdominal epilepsy (AE) is a rare syndrome, even rarer when seen in adults and presents with paroxysmal symptoms favouring an abdominal pathology that result from seizure activity [1]. -

Advances 1N the Medical and Surgical Management of Intractable Partial Complex Seizures* **

Advances 1n the Medical and Surgical Management of Intractable Partial Complex Seizures* ** HOOSHANG HOOSHMAND, M.D. Associate Professor of Neurology, Medical College of Virginia, Health Sciences Division of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond Introduction. Seizures can be due to a variety of ing to body surface is safer and more accurate acute, subacute, or chronic diseases with different (Table 2). As the child grows, there may be a need to etiologies. Clinically, they may manifest as focal or gradually increase the dose of anticonvulsants if generalized phenomena (Table I). Whereas the ma seizure control is poor or if the serum level of the an jority of the patients suffering from partial seizures ticonvulsant starts to decline. are easily controlled with medications, in a small Drug Interaction. The relationship of multiple number of patients treatment may fail. The failure drug therapy to its toxic effects on the brain is quite may be due to incorrect diagnosis or incorrect complicated, and many forms of therapeutic failure therapy. The efficacy of medical treatment for seizure or toxicity can result. disorder depends upon six factors: I) dosage; 2) the Combination ofSimilar Drugs. Failure or toxicity size of the patient; 3) drug interaction; 4) drug may be the result of a combination of phar specificity for the disease; 5) the nature of the disease macologically similar drugs. Such a combination may for which the drug is used; 6) the mode and frequency enhance the side effects of drowsiness and ataxia. The of medication. patient may suffer from these side effects without at Dosage of Anticonvulsant. The dosage of anti taining therapeutic levels of individual anticon convulsant is very important (Table 2) . -

Antiepileptic Drug Treatment in 1959

Antiepileptic Drug Treatment in 1959 The two decades between 1938 and 1958 were notable for a large number of new medicinal com- pounds.Phenytoin was of course the most important, but other drugs, some of which are still prescribed, were introduced at this time. Not only drugs – for the ketogenic diet was also popu- larised in this period. Lennox in his book in 1960 gave a long treatise on drug therapy. Head- ing his list were the bromides, which he found rather ineffective, but barbiturates were greeted enthusiastically. Lennox mentioned that 2,500 compounds had been synthesised, and of these 50 compounds were marketed of which phenobarbital was the most frequently used for epilepsy. He was also enthusiastic about phenytoin, especially for patients ‘with long–standing convul- sions previously unrelieved by phenobarbital’ although Mesantoin outranked it on several points, and indeed he favoured their combined use: ‘Mesantoin and Dilantin are Damon and Pythias in respect to their suitability for joint action. Similarity of action gives a doubled therapeutic effect; the dissimilarity of their side reactions keeps these within bounds.’ Phenacemide was ‘what in athletics might be called a triple threat because, more than any other drug, it acts against each of the three main types of seizures, and especially against the most feared psychomotor seizures. However, it is also a triple threat to the patient himself because of possible effect on the marrow, the liver or the psyche.’ Given one chance in 250 of not surviving this treatment, he Drugs introduced into clinical asked, ‘Is the risk too great?’ Trimethadione practice between 1938 and 1958 (Tridione) ‘heads the list of drugs that are 1938 Dilantin Phenytoin peculiarly beneficial to persons subject to 1941 Diamox Acetazolamide 1946 Tridione Trimethadione petits’. -

Abdominal Epilepsy in a Nigerian Child S

of Ch al ild rn u H o e a J l t A h S of Ch al ild rn u H o e a J l t A h S of Ch al ild CASE REPORT rn u H o e a J l t A h Abdominal epilepsy in a Nigerian child S Garba M Ashir, MB BS, MPHM, FWACP Mohammed A Alhaji, MB BS, MWACP Mustapha M Gofama, MB BS, MWACP Department of Paediatrics, University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri, Nigeria Abdullahi Bello Ibrahim, MB BS Nwaizu C Azuka, MB BS Federal Medical Centre Azare, Bauchi State, Nigeria Corresponding author: G M Ashir ([email protected]) Abdominal epilepsy is an exceptionally rare cause of abdominal pain that is more likely to occur in children than in adults. We report on a child with episodic paroxysmal abdominal pain, accompanied by flatulence, neck pain, tiredness and bilateral weakness of the lower limbs. The findings on physical examination were normal except for Mongolian spots. Haematological investigations, radiographs and an ultrasound scan were normal. The electro-encephalogram showed temporal lobe dysrhythmia during a typical attack. The patient responded well to carbamazepine and remained asymptomatic during the 6 months prior to our writing this article, while taking her treatment regularly. Abdominal epilepsy (AE) is an extremely rare syndrome of Other investigations included an abdominal ultrasound scan epilepsy that is more likely to occur in children than adults. and upper and lower gastro-intestinal tract barium studies. Gastro-intestinal complaints, most commonly abdominal pain, No abnormalities were found. Finally an EEG done during result from seizure activity.1 The syndrome is characterised an episode of the abdominal pain revealed left temporal by: (i) otherwise unexplained, paroxysmal gastro-intestinal dysrhythmia. -

Abdominal Epilepsy As an Unusual Cause Ofabdominal Pain: a Case Report

Abdominal epilepsy as an unusual cause ofabdominal pain: a case report. Yılmaz Yunus1, Ustebay Sefer2, Ulker Ustebay Dondu2, Ozanli Ismail3, Ehi Yusuf2 1. Kafkas University, Medical Faculty, Pediatrics 2. Kafkas University Training and Research Hospital 3. Kars Government Hospital, Department of Pediatrics Abstract: Introduction: Abdominal pain, in etiology sometimes difficult to be defined, is a frequent complaint in childhood. Abdominal epilepsy is a rare cause of abdominal pain. Objectives: In this article, we report on 5 year old girl patient with abdominal epilepsy. Methods: Some investigations (stool investigation, routine blood tests, ultrasonography (USG), electrocardiogram (ECHO) and electrocardiograpy (ECG), holter for 24hr.) were done to understand the origin of these complaints; but no abnormalities were found. Finally an EEG was done during an episode of abdominal pain and it was shown that there were generalized spikes especially precipitated by hyperventilation. The patient did well on valproic acid therapy and EEG was normal 1 month after beginning of the treatment. Discussion: The cause of chronic recurrent paroxymal abdominal pain is difficult for the clinicians to diagnose in childhood. A lot of disease may lead to paroxysmal gastrointestinal symptoms like familial mediterranean fever and porfiria. Abdominal epilepsy is one of the rare but easily treatable cause of abdominal pain. Conclusion: In conclusion, abdominal epilepsy should be suspected in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Keywords: Abdominal epilepsy, abdominal pain, case report. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v16i3.32 Cite as: Yunus Y, Sefer U, Dondu UU, Ismail O, Yusuf E. Abdominal epilepsy as an unusual cause of abdominal pain: a case report.