Alternative Media, Self-Representation and Arab-American Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cumulative Michigan Notable Books List

Author(s) Title Publisher Genre Year Abbott, Jim Imperfect Ballantine Books Memoir 2013 Abood, Maureen Rose Water and Orange Blossoms: Fresh & Classic Recipes from My Lebenese Kitchen Running Press Non-fiction 2016 Ahmed, Saladin Abbott Boom Studios Fiction 2019 Airgood, Ellen South of Superior Riverhead Books Fiction 2012 Albom, Mitch Have a Little Faith: A True Story Hyperion Non-fiction 2010 Alexander, Jeff The Muskegon: The Majesty and Tragedy of Michigan's Rarest River Michigan State University Press Non-fiction 2007 Alexander, Jeff Pandora's Locks: The Opening of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway Michigan State University Press Non-fiction 2010 Amick, Steve The Lake, the River & the Other Lake: A Novel Pantheon Books Fiction 2006 Amick, Steve Nothing But a Smile: A Novel Pantheon Books Fiction 2010 Anderson, Godfrey J. A Michigan Polar Bear Confronts the Bolsheviks: A War Memoir: the 337th Field Hospital in Northern Russia William B. Eerdmans' Publishing Co. Memoir 2011 Anderson, William M. The Detroit Tigers: A Pictorial Celebration of the Greatest Players and Moments in Tigers' History Dimond Communications Photo-essay 1992 Andrews, Nancy Detroit Free Press Time Frames: Our Lives in 2001, our City at 300, Our Legacy in Pictures Detroit Free Press Photography 2003 Appleford, Annie M is for Mitten: A Michigan Alphabet Book Sleeping Bear Press Children's 2000 Armour, David 100 Years at Mackinac: A Centennial History of the Mackinac Island State Park Commission, 1895-1995 Mackinac Island State Historic Parks History 1996 Arnold, Amy & Conway, Brian Michigan Modern: Designed that Shaped America Gibbs Smith Non-fiction 2017 Arnow, Harriette Louisa Simpson Between the Flowers Michigan State University Press Fiction 2000 Bureau of History, Michigan Historical Commission, Michigan Department of Ashlee, Laura R. -

Bibliography of Frank Cook's Early Library

Bibliography of Frank Cook’s Early Library Frank was a pack rat. He saved every book he ever owned. The following list represents Frank’s early readings, for the most part before his love of plants emerged. Frank gathered these books in a small library kept in his brother Ken’s basement shortly before his death. PHI provides this bibliography to friends interested in seeing some of Frank’s early influences. ALLEN, E. B. D. M. (1960). THE NEW AMERICAN POETRY (Reprint. Twelfth Printing.). GROVE PRESS. Amend, V. E. (1965). Ten Contemporary Thinkers. The Free Press. Anonymous. (1965). The Upanishads. Penguin Classics. Armstrong, G. (1969). Protest: Man against Society (2nd ed.). Bantam Books. Asimov, I. (1969). Words of Science. Signet. Atkinson, E. (1965). Johnny Appleseed. Harper & Row. Bach, R. (1989). A Gift of Wings. Dell. Baker, S. W. (1985). The Essayist (5th ed.). HarperCollins Publishers. Baricco, A. (2007). Silk. Vintage. Beavers, T. L. (1972). Feast: A Tribal Cookbook (First Edition.). Doubleday. Beck, W. F. (1976). The Holy Bible. Leader Publishing Company. Berger, T. (1982). Little Big Man. Fawcett. Bettelheim, B. (2001). The Children of the Dream. Simon & Schuster. Bolt, R. (1990). A Man for All Seasons (First Vintage International Edition.). Vintage. brautigan, R. (1981). Hawkline Monster. Pocket. Brautigan, R. (1973). A Confederate General from Big Sur (First Thus.). Ballantine. Brautigan, R. (1975). Willard and His Bowling Trophies (1st ed.). Simon & Schuster. Brautigan, R. (1976). Loading Mercury With a Pitchfork: [Poems] (First Edition.). Simon & Schuster. Brautigan, R. (1978). Dreaming of Babylon. Dell Publishing Co. Brautigan, R. (1979). Rommel Drives on Deep into Egypt. -

April New Books

BROWNELL LIBRARY NEW TITLES, APRIL 2018 FICTION F ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. Queen Anne's lace / Berkley Prime Crime, 2018 While helping Ruby Wilcox clean up the loft above their shops, China comes upon a box of antique handcrafted lace and old photographs. Following the discovery, she hears a woman humming an old Scottish ballad and smells the delicate scent of lavender. Soon strange things start occurring. Could the building be haunted? F ARDEN Arden, Katherine. The bear and the nightingale: a novel / Del Rey, 2017 A novel inspired by Russian fairy tales follows the experiences of a wild young girl who taps the mysterious powers of a precious necklace given to her father years earlier to save her village from dark and dangerous forces. F BALDACCI Baldacci, David. The fallen / Grand Central Publishing, 2018 Amos Decker and his journalist friend Alex Jamison are visiting the home of Alex's sister in Barronville, a small town in western Pennsylvania that has been hit hard economically. When Decker is out on the rear deck of the house talking with Alex's niece, a precocious eight-year- old, he notices flickering lights and then a spark of flame in the window of the house across the way. When he goes to investigate he finds two dead bodies inside and it's not clear how either man died. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. There's something going on in Barronville that might be the canary in the coal mine for the rest of the country. Faced with a stonewalling local police force, and roadblocks put up by unseen forces, Decker and Jamison must pull out all the stops to solve the case. -

LUZERNE COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE LIBRARY New Materials October 01, 2014 - December 31, 2014

LUZERNE COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE LIBRARY New Materials October 01, 2014 - December 31, 2014 CIRCULATING MATERIALS BD436 .F4313 2013 Ferry, Luc. On love: a philosophy for the twenty-first century. English ed. Malden, MA: Polity, c2013. BF575.E55 E65 2014 Epley, Nicholas. Mindwise: how we understand what others think, believe, feel, and want. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, c2014. BF723.C5 E44 2014 The emergent executive: a dynamic field theory of the development of executive function. Boston, MA: Wiley, 2014. BJ1535.A8 D47 2013 Derber, Charles. Sociopathic society: a people's sociology of the United States. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, c2013. BL1923 .S46 2013 Sha, Zhi Gang. Soul healing miracles: ancient and new sacred wisdom, knowledge, and practical techniques for healing the spiritual, mental, emotional, and physical bodies. Dallas, TX: BenBella Books, Inc., c2013. BP605.S2 W75 2013 Wright, Lawrence. Going clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the prison of belief. 1st ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, c2013. BR520 .S836 2014 Stewart, Matthew. Nature's God: the heretical origins of the American republic. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, c2014. D570.9.Y7 M37 2014 Mastriano, Douglas V. Alvin York: a new biography of the hero of the Argonne. Lexington, KY. : University Press of Kentucky, c2014. D767.25.H6 H334 2014 Ham, Paul. Hiroshima, Nagasaki: the real story of the atomic bombings and their aftermath. 1st U.S. ed. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin's Press, 2014, c2011. D769.347 506th .A57 2001 Ambrose, Stephen E. Band of brothers: E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne: from Normandy to Hitler's Eagle's nest. -

Tao Te Ching: the Definitive Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TAO TE CHING: THE DEFINITIVE EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lao Tzu,Jonathan Star | 368 pages | 31 Mar 2004 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9781585422692 | English | Los Angeles, United States Tao te Ching : The Definitive Edition - - Jane English, whose photographs from the integral part of the book, holds a BA from Mount Holyoke College and received her doctorate from the University of Wisconsin in experimental high energy particle physics. In she found her own publishing business, Earth Heart. She was born in Boston, Massachusetts in Product Details. Inspired by Your Browsing History. The I Ching Workbook. The Cathar Tarot. John Matthews. Colette Baron-Reid and Alberto Villoldo. The Wisdom of Avalon Oracle Cards. Colette Baron-Reid. Cool Memories IV. Jean Baudrillard. Wisdom of the Oracle Divination Cards. A Brief History of Everything. Crystal Blueprint. Beatriz Singer. Postcards from Spirit. Sahara Rose Ketabi. Caroline Myss. Exceptional Eye Tricks. Brad Honeycutt. The Occult. Colin Wilson. Caitlin Keegan. Tao te ching: a new version for all seekers , Anusara Press TM. Tao te ching: the new translation from tao te ching : the definative edition , Jeremy P. Tao te ching , Shambhala, Distributed in the U. The tao te ching: a contemporary translation , Fifth Estate. Tao te ching , Shambhala. Tao Te Ching , HarperCollins. Tao te ching: a new version for all seekers , Anusara. Paperback in English - Bilingual edition. Tao te ching: the cornerstone of Chinese culture , Astrolog Pub. Tao te ching , Vega. Tao te ching: a new English version , HarperCollins. Checked Out. Tao te ching , Counterpoint. Tao te ching: an illustrated journey , HarperCollins Publishers. The gate of all marvelous things: a guide to reading the Tao te ching , Red Mansions Pub. -

Reading List

MFA Photography, Video & Related Media Reading List At the start of the program, all students should feel comfortable with the history of photography and the lens-based arts, modern art, the basic thrust of contemporary criticism, and the significance of new media. Each student can adapt the following annotated list to her or his own needs. This list is by no means conclusive but offers a place to start. REQUIRED READING The books listed below are required reading for all students entering the MFA Photography, Video & Related Media program. All students MUST read these books and will be expected to be familiar with the material. We also strongly recommend that you read as many * books as possible from the additional reading list. Fill in whatever gaps you might have in your knowledge. You do not need to purchase these books – most are available at better libraries or universities. Wells, Liz. Photography: A Critical Introduction. Routledge. 2015 (Fifth Edition) (Get e-book here) Cotton, Charlotte. The Photograph as Contemporary Art. Thames and Hudson. 2014. (3rd ed) Rush, Michael. New Media in Art. Thames and Hudson, 2005 Bell, Adam and Charles Traub. Vision Anew: The Lens and Screen Arts. University of California Press. 2015 **Evening, Martin. Adobe Photoshop CC for Photographers (2018 Edition). Focal Press, 2018 ** Required for all photo students entering into Studio: Imaging I & II. If you are working in the moving image or video and taking the other section of Studio: Imaging – the book is not required. ADDITIONAL READING (* are placed next to recommended texts) PHOTOGRAPHY *Adams, Robert. Why People Photograph. -

Graphic Novels: Enticing Teenagers Into the Library

School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts Department of Information Studies Graphic Novels: Enticing Teenagers into the Library Clare Snowball This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University of Technology March 2011 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: _____________________________ Date: _________________________________ Page i Abstract This thesis investigates the inclusion of graphic novels in library collections and whether the format encourages teenagers to use libraries and read in their free time. Graphic novels are bound paperback or hardcover works in comic-book form and cover the full range of fiction genres, manga (Japanese comics), and also nonfiction. Teenagers are believed to read less in their free time than their younger counterparts. The importance of recreational reading necessitates methods to encourage teenagers to enjoy reading and undertake the pastime. Graphic novels have been discussed as a popular format among teenagers. As with reading, library use among teenagers declines as they age from childhood. The combination of graphic novel collections in school and public libraries may be a solution to both these dilemmas. Teenagers’ views were explored through focus groups to determine their attitudes toward reading, libraries and their use of libraries; their opinions on reading for school, including reading for English classes and gathering information for school assignments; and their liking for different reading materials, including graphic novels. -

Globalization, Publishing, and the Marketing of “Hispanic” Identities

Rev9-02 26/2/03 16:33 Página 89 Jill Robbins* ➲ Globalization, Publishing, and the Marketing of “Hispanic” Identities Summary: My article explores the complex Spanish reaction to recent changes in the Spanish-language publishing business as indicative of an ambivalence toward Spain’s place in the new global order, particularly by liberal intellectuals who associate books and bookstores with resistance and solidarity. The purchase of important Spanish publis- hers by international media conglomerates also implies to some a loss of national identity and cultural values, at the same time as the internationalization of the publishing business represents Spain’s incorporation into the European community and the world economy. The European Union, however, and Spain in particular, have globalized and marketed Latin America through business ventures, NGOs and cooperative efforts linked both to the embassies and to the international corporations. The resulting contradictions –the resistance to and welcoming of globalization, the nostalgia for, economic colonization of and rejection of Latin America– affect what is currently published in Spain by Spanish and Latin American authors and how it is marketed. During the summer of 2000, a series of articles appeared in the Spanish daily El País addressing the changes in publishing, both in Spain and abroad, and the pernicious effects of those changes on the real and perceived relevance of bookstores, editors, aut- hors, and books themselves, especially in comparison to the decades immediately follo- wing the Spanish Civil War and World War II. In those years, Leftist Spanish intellec- tuals sensed an affinity with their Latin American counterparts, and that alliance was forged and maintained in Spain through the often clandestine circulation of books by Latin American and exiled Spanish authors. -

Books Located in the National Press Club Archives

Books Located in the National Press Club Archives Abbot, Waldo. Handbook of Broadcasting: How to Broadcast Effectively. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1937. Call number: PN1991.5.A2 1937 Alexander, Holmes. How to Read the Federalist. Boston, MA: Western Islands Publishers, 1961. Call number: JK155.A4 Allen, Charles Laurel. Country Journalism. New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1928. Alsop, Joseph and Stewart Alsop. The Reporter’s Trade. New York: Reynal & Company, 1958. Call number: E741.A67 Alsop, Joseph and Catledge, Turner. The 168 Days. New York: Doubleday, Duran & Co., Inc, 1938. Ames, Mary Clemmer. Ten Years in Washington: Life and Scenes in the National Capital as a Woman Sees Them. Hartford, CT: A. D. Worthington & Co. Publishers, 1875 Call number: F198.A512 Andrews, Bert. A Tragedy of History: A Journalist’s Confidential Role in the Hiss-Chambers Case. Washington, DC: Robert Luce, 1962. Anthony, Joseph and Woodman Morrison, eds. Best News Stories of 1924. Boston, MA: Small, Maynard, & Co. Publishers, 1925. Atwood, Albert (ed.), Prepared by Hershman, Robert R. & Stafford, Edward T. Growing with Washington: The Story of Our First Hundred Years. Washington, D.C.: Judd & Detweiler, Inc., 1948. Baillie, Hugh. High Tension. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1959. Call number: PN4874.B24 A3 Baker, Ray Stannard. American Chronicle: The Autobiography of Ray Baker. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1945. Call number: PN4874.B25 A3 Baldwin, Hanson W. and Shepard Stone, Eds.: We Saw It Happen: The News Behind the News That’s Fit to Print. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1938. Call number: PN4867.B3 Barrett, James W. -

Realization of Internet Services in a Media Company – the Case of Bertelsmann Professional Information

RESEARCH n A b s t r a c t n Realization of Internet Services in a a m s The Internet offers a new channel for l e t Media Company – the Case of distribution of content and provision of r e B new services to media companies. Med- , t e Bertelsmann Professional ia companies are adopting this. In- n r e depth analysis of products, processes t n I Information and Information Technology infrastruc- , y n ture in the companies is still missing. a p The aim of this paper is to discuss this m o THOMAS HESS question based on the case of Bertels- c a i d mann Professional Information. Bertels- e m mann Professional Information : s d developed new Internet services from r o 1996 to 1997. As one of the results of w y e this study, several new topics for re- K search have been identified: opportu- nities and restrictions of automation of selection and packaging of content, INTRODUCTION than at home. Because the PC is an organization of data flow while using established and well-known front end different target media and outsourcing Products of the media industry can be in the office environment, there is no of information technology functions in digitized completely, ie digitally pro- need for a change in media consump- a media company. cessed and distributed. Therefore, en- tion habits among target customers. terprises in the media industry depend Therefore, a publisher of professional on innovations in information tech- information has been selected as an nology more than most other example for this case study. -

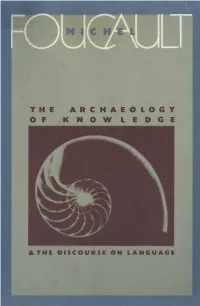

Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF KNOWLEDGE &: THE DISCOURSE ON LANGUAGE THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF KNOWLEDGE Also by Michel Foucault Madness and Civilization: A History ofInsanity in the Age of Reason The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother. .. A Case of Parricide in the Nineteenth Century Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison The History of Sexuality, Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Herculine Barbin , Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-Century French Hermaphrodite Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 The Foucault Reader (edited by Paul Rabinow) MICHEL FOUCAULT THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF KNOWLEDGE AND THE I)ISCQURSE ON LANGUAGE Translated from the French by A. M. Sheridan Smith PANTHEON BOOKS, NEW YORK Copyright © 1972 by Tavistock Publications Limited All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Pub lished in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in Great Britain by Tavistock Publications, Ltd. Originally published in France under the title L'Archeologie du Savoir by Editions Gallimard. © Editions Gallimard 1969 The DiscllUrse un Language (Appendix) was,originally published in French under the title L'ordre du discllUrs by Editions Gallimard. © Editions Gallimard 1971. English translation by Rupert Swyer. Copyright © 1971 by Social Science Informatiun. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Foucault, Michel. The archaeology of knowledge. (World of man) Translation of�archeologie du savoir. Includes the author's The Discourse on Language, translation of�ordre du discours I. -

18416.Brochure Reprint

RANDOMRANDOM HOUSEHOUSE PremiumPremium SalesSales && CustomCustom PublishingPublishing Build Your Next Promotion with THE Powerhouse in Publishing . Random House nside you’ll discover a family of books unlike any other publisher. Of course, it helps to be the largest consumer book publisher in the world, but we wouldn’t be successful in coming up with creative premium book offers if we didn’t have Ipeople who understand what marketers need. Drop in and together we’ll design your blueprint for success. Health & Well-Being You’re in good hands with a medical staff that includes the American Heart Association, American Medical Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cancer Society, Dr. Andrew Weil and Deepak Chopra. Millions of consumers have received our health books through programs sponsored by pharmaceutical, health insurance and food companies. Travel Targeting the consumer or business traveler in a future promotion? Want the #1 brand name in travel information? Then Fodor’s, with its ever-expanding database to destina- tions worldwide, is the place to be. Talk to us about how to use Fodor’s books for your next convention or meeting and even about cross-marketing opportunities and state-of- the-art custom websites. If you need beauti- fully illustrated travel books, we also publish the Knopf Guides, Photographic Journey and other picture book titles. Call 1.800.800.3246 Visit us on the Web at www.randomhouse.com 2 Cooking & Lifestyle Imagine a party with Julia Child, Martha Stewart, Jean-Georges, and Wolfgang Puck catering the affair. In our house, we have these and many more award winning chefs and designers to handle all the details of good living.