The Kyambogo Years (1990 – 1993)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

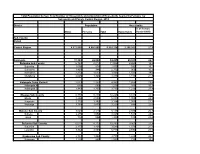

Presidential Election Nullified Polling Stations 2021 District Constituency Scounty Parish POLLING STATION VOTERS No

Presidential Election Nullified Polling Stations 2021 District Constituency Scounty Parish POLLING STATION VOTERS No. 1 32 MUKONO 231 MUKONO MUNICIPALITY 01 GOMA DIVISION 05 SEETA WARD 31 GOSHEN LAND [NAK-Z] 823 2 32 MUKONO 176 MUKONO COUNTY NORTH 02 KYAMPISI 14 KYABAKADDE 08 KASALA 412 3 32 MUKONO 176 MUKONO COUNTY NORTH 02 KYAMPISI 16 NTONTO 05 KASENENE 419 4 32 MUKONO 176 MUKONO COUNTY NORTH 04 NAMA 20 NAMAWOJJOLO 07 NAMAWOJJOLO ISLAMIC P/S [N-Z] 933 5 32 MUKONO 176 MUKONO COUNTY NORTH 04 NAMA 20 NAMAWOJJOLO 08 NAMAWOJJOLO WEST [N-Z] 757 062 KAWEMPE DIVISION 6 12 KAMPALA NORTH 01 KAWEMPE DIVISION 01 BWAISE I 26 EXCEL PR. SCH.(KI-M) 851 062 KAWEMPE DIVISION 7 12 KAMPALA NORTH 01 KAWEMPE DIVISION 01 BWAISE I 27 EXCEL PR. SCH.(N-NAL) 794 8 03 BUNDIBUGYO 014 BWAMBA COUNTY 11 BUSUNGA TOWN COUNCIL 31 LAMIA WARD 05 RUTOOBO SDA CHURCH 139 9 119 KYOTERA 194 KYOTERA COUNTY 04 KIRUMBA 24 BYERIMA 01 KAMPUNGU P/SCHOOL 853 10 119 KYOTERA 194 KYOTERA COUNTY 07 NABIGASA 35 KYASSIMBI 01 KATTENJU PLAYGROUND 604 11 119 KYOTERA 194 KYOTERA COUNTY 07 NABIGASA 35 KYASSIMBI 02 BULYANA MOSQUE (A-M) 341 12 119 KYOTERA 194 KYOTERA COUNTY 01 KABIRA 03 KYANIKA 04 BBANDA PRI. SCH 752 273 MAWOGOLA NORTH 13 45 SSEMBABULE COUNTY 01 LUGUSULU 19 KAIRASYA 03 KIZAANO PENTECOSTAL CHURCH 182 273 MAWOGOLA NORTH 14 45 SSEMBABULE COUNTY 01 LUGUSULU 22 MWITSI 04 NYAKATABO 226 15 36 RAKAI 249 BUYAMBA COUNTY 06 LWAMAGGWA 25 KIBUUKA 01 KIBUUKA P/SCHOOL 469 16 36 RAKAI 249 BUYAMBA COUNTY 06 LWAMAGGWA 25 KIBUUKA 02 KYANIKA CATHOLIC CHURCH 564 17 32 MUKONO 176 MUKONO COUNTY NORTH 04 NAMA 20 NAMAWOJJOLO 04 BWEFULUMYA EAST-AT FOREST HILL 501 18 12 KAMPALA 067 RUBAGA DIVISION SOUTH 01 RUBAGA DIVISION 07 NDEEBA 22 LATE J.B. -

Uganda Chapter Annual Programmes Narrative Report for the Period January

FORUM FOR AFRICAN WOMEN EDUCATIONALISTS (FAWE) UGANDA CHAPTER ANNUAL PROGRAMMES NARRATIVE REPORT FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY – DECEMBER 2016 Plot 328, Bukoto Kampala P.O. Box 24117, Kampala. Tel. 0392....... E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.faweuganda.org 1 1.0 Introduction This annual programme narrative report for the year ending 2016 has been prepared as a reference document for assessing progress of activities implemented by FAWEU during the period under review (i.e. Jan – Dec 2016). The report provides feedback on the progress made in the achievements of set goals, objectives and targets and the challenges met in implementation of activities during the period January – December 2016. 1.2 Overview of the FAWEU Programme The FAWEU programme comprises of a number of projects where majority of them run for a period ranging from one year to three years. The projects address different aspects that are very critical in the empowerment of women and girls to enable them fully participate in the development at all levels. The aspects include; the scholarship component (i.e. school fees/Tuition fees and functional fees, scholastic materials and basic requirements, meals and accommodation and transport), the Advocacy component for awareness creation and fostering positive practices and strategies among different stakeholders for learning and development. Such aspects include; Adolescent Sexual reproductive health (awareness raising through provision of age appropriate information and advocacy), Violence Against, mentoring, counselling and guidance among others. 1. SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM In a bid to enable vulnerable children from disadvantaged backgrounds, FAWEU provides educational support in collaboration with different funders. These include the following; 1.1 KARAMOJA SECONDARY SCHOOL SCHOLARSHIP FAWEU and Irish Aid have been in partnership since 2005 implementing a secondary education programme for vulnerable girls 65% and boys 35%. -

Kyambogo University Fact Book

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY FACT BOOK Table of Contents Table of Figures: ............................................................................................................................................ 3 List of Tables: ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Preamble: ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgement ....................................................................................................................................... 8 1.0: GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY: ................................................. 10 1.1: Vision: To be a Centre of Academic and Professional Excellence: ............................................... 10 1.2: Mission: ...................................................................................................................................... 10 1.3: Kyambogo Motto: ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.4: Core values: ................................................................................................................................ 10 1.5: Kyambogo University Administrative -

Uganda at 50: the Past, the Present and the Future

UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 ii A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue 2012 Published by ACODE P.O. Box 29836, Kampala - UGANDA Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Kabarungi, N. (2013). Uganda at 50: The Past, the Present and the Future. A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue. ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No.17, 2013. Kampala. © ACODE 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is exempted from this restriction. ISBN 978 9970 34 009 5 Cover Photo: A Cross section of participants attending the Uganda @50 in 4 Hours Dialogue held on October 3, 2012 at Sheraton Hotel in Kampala. -

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

Makerere University Business School

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY BUSINESS SCHOOL ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT PRIVATE ADMISSIONS, 2018/2019 ACADEMIC YEAR PRIVATE THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ADMITTED TO THE FOLLOWING PROGRAMME ON PRIVATE SCHEME BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING (MUBS) COURSE CODE ACC INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0801/525 NAMIRIMU Carolyne Mirembe 2017 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.8 2 U0083/542 ANKUNDA Crissy 2017 F U 46 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 3 U0956/649 SSALI PAUL 2017 M U 49 NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 45.4 4 U0169/626 MUHANUZI Robert 2017 M U 102 ST.ANDREA KAHWA'S COL., HOIMA 45.2 5 U0048/780 NGANDA Nasifu 2017 M U 88 MASAKA SECONDARY SCHOOL 44.5 6 U0178/502 ASHABA Lynn 2017 F U 12 CALTEC ACADEMY, MAKERERE 43.6 7 U0060/583 ATUGONZA Sharon Mwesige 2017 F U 13 TRINITY COLLEGE, NABBINGO 43.6 8 U0763/546 NYALUM Connie 2017 F U 43 BUDDO SEC. SCHOOL 43.3 9 U2546/561 PAKEE PATIENCE 2016 F U 55 PRIDE COLLEGE SCHOOL MPIGI 43.3 10 U0334/612 KYOMUGISHA Rita Mary 2011 F U 55 UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 43.1 11 U0249/532 MUGANGA Diego 2017 M U 55 ST.MARIA GORETTI S.S, KATENDE 42.1 12 U1611/629 AHUURA Baseka Patricia 2017 F U 34 OURLADY OF AFRICA SS NAMILYANGO 41.5 13 U0923/523 NABUUMA MAJOREEN 2017 F U 55 ST KIZITO HIGH SCH., NAMUGONGO 41.5 14 U2823/504 NASSIMBWA Catherine 2017 F U 55 ST. HENRY'S COLLEGE MBALWA 41.3 15 U1609/511 LUBANGAKENE Innocent 2017 M U 27 NAALYA SSS 41.3 16 U0417/569 LUBAYA Racheal 2017 F U 16 LUZIRA S.S.S. -

Professional Development Practices and Service Delivery of Academic Staff in Kampala International and Kyambogo Universities in Uganda

Journal of Popular Education in Africa June 2018, Volume 2, Number 6 ISSN 2523-2800 (online) Citation: Kulthum, N; Tusiime, H.M & Kyaligonza, R. (2018). Professional Development Practices and Service Delivery of Academic Staff in Kampala International and Kyambogo Universities in Uganda. Journal of Popular Education in Africa. 2(6), 109 – 119. Professional Development Practices and Service Delivery of Academic Staff in Kampala International and Kyambogo Universities in Uganda By Nabunya Kulthum, Hilary Mukwenda Tusiime, Robert Kyaligonza Abstract The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between professional development practices and service delivery of academic staff in Kampala International and Kyambogo universities. Specifically, the study examined the relationship between professional development practices on teaching, research and community service delivery of academic staff. The study was guided by correlational and cross-sectional designs. A total of 478 respondents were involved in the study. These included 187 from KIU and 291 from Kyambogo University. Academic staff were sampled using stratified sampling techniques while administrative staff were sampled using purposive sampling. Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire for academic staff and interview guide for administrative staff. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics which included, student’s-test, ANOVA, correlation and simple linear regression analyses. Qualitative data was analysed using thematic analysis method. The main findings of the study were that professional development practices were significantly related with teaching service delivery of academic staff, while it (PDPs) insignificantly related with research service delivery and community service delivery of academic staff. It was therefore concluded that PDPs significantly relates with academic staff service delivery. -

Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities KAMPALA, UGANDA

Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities KAMPALA, UGANDA Urban Environmental Profile Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities KAMPALA, UGANDA Urban Environmental Profile COPYRIGHT © 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. September 2015 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Publishing and Knowledge Division, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, -

Nakawa Division Grades

DIVISION PARISH VILLAGE STREET AREA GRADE NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO24 LUTHULI 4TH CLOSE 2-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO25 LUTHULI 1ST CLOSE 1-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO26 LUTHULI 5TH CLOSE 1-9 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO27 LUTHULI 2ND CLOSE 1-10 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BLOCK 1 TO28 LUTHULI RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MBUYA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MIZINDALO ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MPANGA CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II MUZIWAACO ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II PRINCESS ANNE DRIVE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II ROBERT MUGABE ROAD. 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BAZARRABUSA DRIVE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BINAYOMBA RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BINAYOMBA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II BUGOLOBI STREET 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II FARADAY ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II FARADY ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II HUNTER CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW II KULUBYA CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I BANDALI RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I HANLON ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I MUWESI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I NYONDO CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I SALMON RISE 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I SPRING ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUGOLOBI BUNGALOW I YOUNGER AVENUE 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I KALONDA KISASI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I KALONDA SERUMAGA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MUKALAZI KISASI ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MUKALAZI MUKALAZI ROAD 1 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I MULIMIRA OFF MOYO CLOSE 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I NTINDA- OLD KIRA ZONE NTINDA- OLD KIRA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I OLD KIRA ROAD BATAKA ROAD 1 NAKAWA BUKOTO I OLD KIRA ROAD LUTAYA -

Upf Promotions 2021

1. AIP – IP (.) S/NO FORCE NO RANK NAMES STATION/UNIT 1 1/185 AIP IGULOT JEAN JANSSEN APAC 2 A/1003 AIP SANYA VICENT BUKEDI SOUTH REG. HQTRS 3 A/1081 AIP AGABA PADDY AIRWING 4 A/1114 AIP AYARO JOHN ASWA REGION H/ QTRS 5 A/1134 AIP AGENOMUNGU AGNES NEBBI 6 A/1190 AIP ABALO JOYCE LIRA 7 A/1192 AIP ABIRIA BEATRICE KIBOGA P/STN 8 A/12/35 AIP AMONG FLORENCE CID HQTRS 9 A/1208 AIP ABURA EMMANUEL WILSON LOGISTICS NAMANVE 10 A/1219 AIP AMURET JAMES ABIM 11 A/1220 AIP AKURUT RACHEAL POLICE HEADQUARTERS/ICT 12 A/1222 AIP AYIKO JOEL CID HQTRS 13 A/1227 AIP ASIIMWE EZRA WAMALA REG. HQTRS 14 A/1231 AIP ASIIMWE DENNIS CT/VIPPU 15 A/1238 AIP ARYAO CHRISTINE TECHNICAL SERVICES 16 A/1240 AIP ATWORO SILVESTO CT/VIPPU/VIS 17 A/1262 AIP ATIKU SHIRAJI NORTH KYOGA REGION 18 A/1264 AIP ASASIIRA BRENDAH EAST KYOGA REGION 19 A/1279 AIP ARIMA HEZRON WEST NILE REGION 20 A/1280 AIP AUDO DEBORAH WANDEGEYA 21 A/1313 AIP AMAMUKE FESTUS OLEMA KOBOKO 22 A/1314 AIP ADRONI BERNARD MARACHA 23 A/1325 AIP AILO BETTY LIRA 24 A/1330 AIP ATUHAIRE CALEB KMP/EAST 25 A/1331 AIP ALUONZI STEPHEN KAKIRI 26 A/1347 AIP AMODOI WILLIAM SILVER KAMULI 27 A/1356 AIP AKAMUHABWA AFRICANO KYANKWANZI P/STN Page 1 of 98 28 A/1359 AIP AROBA TERESA ENTEBBE 29 A/1363 AIP AHABWE DENIS MUBENDE P/STN 30 A/1449 AIP ALUPO ANNA GRACE KIRA DIVISION 31 A/1457 AIP ARIA ALICE GULU DISTRICT 32 A/1459 AIP ANGOIS LAWRENCE MITYANA P/STN 33 A/1465 AIP ADEKERE WILBERT GULU DISTRICT 34 A/1472 AIP AMAYO NICHOLAS CID HQTRS 35 A/1622 AIP ACAYE PHILLIPS PTS KABALYE 36 A/1638 AIP AKELLO DOROTHY CT TECHNICAL SERVICES -

Kyambogo University National Merit Admission 2019-2020

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE COURSE CODE AFD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U1223/539 BALABYE Alice Esther 2018 F U 16 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.9 2 U1223/589 NANYONJO Jovia 2018 F U 85 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.7 3 U0801/501 NAKIMBUGE Kevin 2018 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.9 4 U1688/510 TUMWESIGE Hilda Sylivia 2018 F U 34 KYADONDO SS 45.8 5 U1224/536 AKELLO Jovine 2018 F U 31 ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 45.8 6 U0083/693 TUKASHABA Catherine 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 7 U1609/503 OTHIENO Tophil 2018 M U 54 NAALYA SSS 45.7 8 U0046/508 ATUHAIRE Comfort 2018 F U 123 MARYHILL HIGH SCHOOL 45.6 9 U2236/598 NABULO Gorret 2018 F U 52 ST.MARY'S COLLEGE, LUGAZI 45.6 10 U0083/541 BEINOMUGISHA Izabera 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.5 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF VOCATIONAL STUDIES IN AGRICULTURE WITH EDUCATION COURSE CODE AGD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0059/548 SSEGUJJA Emmanuel 2018 M U 97 BUSOGA COLLEGE, MWIRI 33.2 2 U1343/504 AKOLEBIRUNGI Cecilia 2018 F U 30 AVE MARIA SECONDARY SCHOOL 31.7 3 U3297/619 KIYIMBA Nasser 2018 M U 51 BULOBA ROYAL COLLEGE 31.4 4 U1476/577 KIRYA Brian 2018 M U 93 RAINBOW HIGH SCHOOL, BUDAKA 31.2 5 U0077/619 KIZITO -

Annie Begumisa (Phd.) ACADEMIC REGISTRAR Approved By: Page 1 of 12 Chairman Admissions Board BACHELOR of ENGINEERING in AUTOMATIVE POWER ENGINEERING

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2018/2019 ACADEMIC YEAR (NATIONAL MERIT) THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ADMITTED TO THE FOLLOWING PROGRAMME ON GOVERNMENT SCHEME BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE COURSE CODE AFD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0083/551 ASHABAHEBWA Rachael 2017 F U 46 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 48 2 U1223/669 KANYESIGYE Edwin 2017 M U 117 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 46.2 3 U0063/516 AMOIT Megan Angel 2017 F U 54 MT.ST.MARY'S, NAMAGUNGA 46.2 4 U1107/502 SSEWANYANA Courage 2017 M U 116 ST. LAWRENCE S.S, SSONDE 46.1 5 U0060/627 ATUKUNDA Noeline 2017 F U 50 TRINITY COLLEGE, NABBINGO 46 6 U2929/580 WALUDE Deborah 2017 F U 17 SEETA H/S GREEN CAMPUS, MUKONO 46 7 U1223/661 BAINOMUGISA Judith 2017 F U 42 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 45.9 8 U0459/502 NAKIMBUGWE Latifah 2017 F U 55 KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 45.8 9 U1611/635 AMANIYO Doreen 2017 F U 03 OURLADY OF AFRICA SS NAMILYANGO 45.8 10 U0763/503 GULAYITA Anna 2017 F U 63 BUDDO SEC. SCHOOL 45.7 11 U2177/522 NABIRYE Gorret 2017 F U 16 MBOGO COLLEGE SCHOOL 45.7 BACHELOR OF VOCATIONAL STUDIES IN AGRICULTURE WITH EDUCATION COURSE CODE AGD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0437/529 MULEME Moses 2017 M U 49 KABAALE SANJE S.S. 36.2 2 U2139/524 NTEZA Steven 2017 M U 51 MUMSA HIGH SCHOOL, MITYANA 34.5 3 U1907/502 SENTONGO Joseph 2017 M U 32 NAKASEKE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE 34.3 4 U0082/517 MUHWEZI Julius 2017 M U 110 ST.KAGGWA BUSHENYI HIGH SCH.