A Summary of Terrestrial and Freshwater Invertebrate Conservation in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Surveys and Stewardship Activities, 2013

Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Surveys and Stewardship Activities, 2013 Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Colin Murray Report No. 2014-01 Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Box 24, 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, Manitoba R3J 3W3 www.manitoba.ca/conservation/cdc Recommended Citation: Murray, C. 2014. Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Surveys and Stewardship Activities, 2013. Report No. 2014-01. Manitoba Conservation Data Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba. v+41 pp. Images: Unless otherwise noted, all images are ©Manitoba Conservation Data Centre. Cover image: View of the Assiniboine River and Beaver Creek valleys looking south from a top the valley plateau. Inset is a White Flower Moth (Schinia bimatris) at rest. Photographed at Spruce Woods Provincial Park. Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Surveys and Stewardship Activities, 2013 By Colin Murray Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Wildlife Branch Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship Winnipeg, Manitoba Executive Summary In 2013, the Manitoba Conservation Data Center (MBCDC) added nearly 1,240 new occurrences to its Biodiversity Geospatial Database. This represents thousands of species at risk (SAR) observations including 27 plant and 51 animal species. Observations were gathered by MBCDC staff and also submitted to the MBCDC by individuals and other organisations. This information will further enhance our understanding of biodiversity in Manitoba and guide research, development, and educational efforts. This year MBCDC field surveys targeted 21 species which are listed under the federal Species at Risk Act, assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), and listed under Manitoba’s Endangered Species and Ecosystems Act, and especially occurring in the mixed-grass prairie and sandhill areas of southwestern Manitoba. -

Survey of Lepidoptera of the Wainwright Dunes Ecological Reserve

SURVEY OF LEPIDOPTERA OF THE WAINWRIGHT DUNES ECOLOGICAL RESERVE Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 159 SURVEY OF LEPIDOPTERA OF THE WAINWRIGHT DUNES ECOLOGICAL RESERVE Doug Macaulay Alberta Species at Risk Report No.159 Project Partners: i ISBN 978-1-4601-3449-8 ISSN 1496-7146 Photo: Doug Macaulay of Pale Yellow Dune Moth ( Copablepharon grandis ) For copies of this report, visit our website at: http://www.aep.gov.ab.ca/fw/speciesatrisk/index.html This publication may be cited as: Macaulay, A. D. 2016. Survey of Lepidoptera of the Wainwright Dunes Ecological Reserve. Alberta Species at Risk Report No.159. Alberta Environment and Parks, Edmonton, AB. 31 pp. ii DISCLAIMER The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department or the Alberta Government. iii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... vi 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY AREA ............................................................................................................. 2 3.0 METHODS ................................................................................................................... 6 4.0 RESULTS .................................................................................................................... -

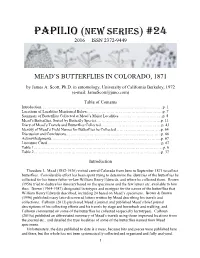

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens. -

Behr's Hairstreak (Satyrium Behrii)

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Adopted under Section 44 of SARA Recovery Strategy for the Behr’s Hairstreak (Satyrium behrii) in Canada Behr’s Hairstreak 2014 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2014. Recovery Strategy for the Behr’s Hairstreak (Satyrium behrii) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. 26 pp. + Appendix. For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry. Cover illustration: Neil K. Dawe Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement du porte-queue de Behr (Satyrium behrii) au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2014. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. RECOVERY STRATEGY FOR THE BEHR’S HAIRSTREAK (Satyrium behrii) IN CANADA 2014 Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada. In the spirit of cooperation of the Accord, the Government of British Columbia has given permission to the Government of Canada to adopt the “Recovery Strategy for Behr’s Hairstreak (Satyrium behrii) in British Columbia” (Part 2) under Section 44 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). -

Species at Risk Portfolio: May 2020

South Okanagan Similkameen Conservation Program ABSTRACT This document summarizes recovery strategy direction for nine Species at Risk Act (SARA) species at risk found in the Okanagan. It provides links to detailed information for each species and is intended to support strategies for avoidance and mitigation of impacts associated with land development. The portfolio is intended for a qualified environmental professional audience to support them in completing SPECIES AT RISK environmental assessments and provide direction that prevents destruction of Critical Habitat. Alison Peatt, M.Sc., RPBio, FAPB PORTFOLIO: MAY 2020 Guidance for Qualified Environmental Professionals (QEP) providing advice on protection of Critical Habitat APRIL 2020 Version SPECIES AT RISK PORTFOLIO: MAY 2020 Applying Critical Habitat Protection on the Ground Species at Risk Photo Portfolio These outreach materials were developed to help support identification and protection of Critical Habitat for nine Species at Risk Act (SARA) Schedule 1 listed Endangered and Threatened species found in the Okanagan. Materials are designed to help Qualified Environmental Professionals (QEPs) and others identify Critical Habitat attributes and consider what strategies for avoidance and mitigation of land use impacts will conserve Critical Habitat and prevent its destruction. These materials are intended to help translate direction in recovery strategies into actions on the ground, thereby strengthening protection of Critical Habitat attributes and the species that depend on them. This document is not intended to be a substitute for professional opinion, or to reduce reliance by professionals on the recovery strategy direction. Acknowledgement: Thanks to Bryn White, Jared Maida and Jamie Leathem for their review and edits to this document. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

Invertebrates

State Wildlife Action Plan Update Appendix A-5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Fact Sheets INVERTEBRATES Conservation Status and Concern Biology and Life History Distribution and Abundance Habitat Needs Stressors Conservation Actions Needed Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 2015 Appendix A-5 SGCN Invertebrates – Fact Sheets Table of Contents What is Included in Appendix A-5 1 MILLIPEDE 2 LESCHI’S MILLIPEDE (Leschius mcallisteri)........................................................................................................... 2 MAYFLIES 4 MAYFLIES (Ephemeroptera) ................................................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Cinygmula gartrelli) .................................................................................................................... 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia falcula) ............................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia jenseni) ............................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Siphlonurus autumnalis) .............................................................................................................. 4 [unnamed] (Cinygmula gartrelli) .................................................................................................................... 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia falcula) ........................................................................................................... -

Specimen Records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895

Catalog: Oregon State Arthropod Collection 2019 Vol 3(2) Specimen records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895 Jon H. Shepard Paul C. Hammond Christopher J. Marshall Oregon State Arthropod Collection, Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis OR 97331 Cite this work, including the attached dataset, as: Shepard, J. S, P. C. Hammond, C. J. Marshall. 2019. Specimen records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895. Catalog: Oregon State Arthropod Collection 3(2). (beta version). http://dx.doi.org/10.5399/osu/cat_osac.3.2.4594 Introduction These records were generated using funds from the LepNet project (Seltmann) - a national effort to create digital records for North American Lepidoptera. The dataset published herein contains the label data for all North American specimens of Lycaenidae and Riodinidae residing at the Oregon State Arthropod Collection as of March 2019. A beta version of these data records will be made available on the OSAC server (http://osac.oregonstate.edu/IPT) at the time of this publication. The beta version will be replaced in the near future with an official release (version 1.0), which will be archived as a supplemental file to this paper. Methods Basic digitization protocols and metadata standards can be found in (Shepard et al. 2018). Identifications were confirmed by Jon Shepard and Paul Hammond prior to digitization. Nomenclature follows that of (Pelham 2008). Results The holdings in these two families are extensive. Combined, they make up 25,743 specimens (24,598 Lycanidae and 1145 Riodinidae). -

Arizona Wildlife Notebook

ARIZONA WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ARIZONA WILDLIFE NOTEBOOK GARRY ROGERS Praise for Arizona Wildlife Notebook “Arizona Wildlife Notebook” by Garry Rogers is a comprehensive checklist of wildlife species existing in the State of Arizona. This notebook provides a brief description for each of eleven (11) groups of wildlife, conservation status of all extant species within that group in Arizona, alphabetical listing of species by common name, scientific names, and room for notes. “The Notebook is a statewide checklist, intended for use by wildlife watchers all over the state. As various individuals keep track of their personal observations of wildlife in their specific locality, the result will be a more selective checklist specific to that locale. Such information would be vitally useful to the State Wildlife Conservation Department, as well as to other local agencies and private wildlife watching groups. “This is a very well-documented snapshot of the status of wildlife species – from bugs to bats – in the State of Arizona. Much of it should be relevant to neighboring states, as well, with a bit of fine-tuning to accommodate additions and deletions to the list. “As a retired Wildlife Biologist, I have to say Rogers’ book is perhaps the simplest to understand, yet most comprehensive in terms of factual information, that I have ever had occasion to peruse. This book should become the default checklist for Arizona’s various state, federal and local conservation agencies, and the basis for developing accurate local inventories by private enthusiasts as well as public agencies. "Arizona Wildlife Notebook" provides a superb starting point for neighboring states who may wish to emulate Garry Rogers’ excellent handiwork. -

Papilio (New Series) # 25 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) # 25 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 ERNEST J. OSLAR, 1858-1944: HIS TRAVEL AND COLLECTION ITINERARY, AND HIS BUTTERFLIES by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract. Ernest John Oslar collected more than 50,000 butterflies and moths and other insects and sold them to many taxonomists and museums throughout the world. This paper attempts to determine his travels in America to collect those specimens, by using data from labeled specimens (most in his remaining collection but some from published papers) plus information from correspondence etc. and a few small field diaries preserved by his descendants. The butterfly specimens and their localities/dates in his collection in the C. P. Gillette Museum (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado) are detailed. This information will help determine the possible collection locations of Oslar specimens that lack accurate collection data. Many more biographical details of Oslar are revealed, and the 26 insects named for Oslar are detailed. Introduction The last collection of Ernest J. Oslar, ~2159 papered butterfly specimens and several moths, was found in the C. P. Gillette Museum, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado by Paul A. Opler, providing the opportunity to study his travels and collections. Scott & Fisher (2014) documented specimens sent by Ernest J. Oslar of about 100 Argynnis (Speyeria) nokomis nokomis Edwards labeled from the San Juan Mts. and Hall Valley of Colorado, which were collected by Wilmatte Cockerell at Beulah New Mexico, and documented Oslar’s specimens of Oeneis alberta oslari Skinner labeled from Deer Creek Canyon, [Jefferson County] Colorado, September 25, 1909, which were collected in South Park, Park Co. -

Porte-Queue De Behr (Satyrium Behrii) Au Canada

PROPOSITION Loi sur les espèces en péril Série de Programmes de rétablissement Adoption en vertu de l’article 44 de la LEP Programme de rétablissement du porte-queue de Behr (Satyrium behrii) au Canada Porte-queue de Behr 2014 Référence recommandée : Environnement Canada. 2014. Programme de rétablissement du porte-queue de Behr (Satyrium behrii) au Canada [Proposition], Série de Programmes de rétablissement de la Loi sur les espèces en péril, Environnement Canada, Ottawa, 31 p. + annexe. Pour télécharger le présent programme de rétablissement ou pour obtenir un complément d’information sur les espèces en péril, incluant les rapports de situation du Comité sur la situation des espèces en péril au Canada (COSEPAC), les descriptions de la résidence, les plans d’action et d’autres documents connexes sur le rétablissement, veuillez consulter le Registre public des espèces en péril. Illustration de la couverture : Neil K. Dawe Also available in English under the title "Recovery Strategy for the Behr’s Hairstreak (Satyrium behrii) in Canada [Proposed]". © Sa Majesté la Reine du chef du Canada, représentée par la ministre de l’Environnement, 2014. Tous droits réservés. ISBN No de catalogue Le contenu du présent document (à l’exception des illustrations) peut être utilisé sans permission, mais en prenant soin d’indiquer la source. PROGRAMME DE RÉTABLISSEMENT DU PORTE-QUEUE DE BEHR (Satyrium behrii) AU CANADA 2014 En vertu de l’Accord pour la protection des espèces en péril (1996), les gouvernements fédéral, provinciaux et territoriaux ont convenu de travailler ensemble pour établir des mesures législatives, des programmes et des politiques visant à assurer la protection des espèces sauvages en péril partout au Canada. -

Yellow Sandverbena (Abronia Latifolia Eschsch.)

PLANT OF THE YEAR Yellow Sandverbena (Abronia latifolia Eschsch.) Patricia Whereat-Phillips Sonoma, California grew up near the southern edge of the Coos Bay dune Miluk languages of Coos Bay: tłǝmqá’yawa, which trans- sheet. There are many green “old friends” I love to lates roughly “the scented one.” meet while hiking in the ta’an (a Hanis Coos word Yellow sandverbena is not a true verbana (Verbena- Ifor dunes): a Port Orford cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoni- ceae). The genusAbronia is a member of the four o’clock ana) growing above a dune lake, purple flowered seashore family (Nyctaginaceae). This family is represented in lupines (Lupinus littoralis), wild strawberries (Fragaria Oregon by just four species of Abronia and three spe- chiloensis), among many others. But one beach-hug- cies of Mirabilis (four o’clock). In the genus Abronia, ging plant has stood out there are two species on for me, not only for its the Oregon coast, yellow bright yellow flowers, but sandverbena (A. latifolia) especially for its strong and pink sandverbena (A. sweet smell: the yellow umbellata). Pink sand- sandverbena. I can’t recall verbena resembles the any other native beach or yellow-flowering species, dune plant that has such but its leaves are longer strongly scented flowers. and narrower, and the Yellow sandver- flowers are a vivid pink bena grows from British with white centers. Some Columbia to the central report pink sandver- California coast and is bena has no scent; others usually found above the report it has a scent, but high tide line beaches and is lighter than its yellow in coastal sand dunes.