Alpine Roulette the Impermanence of Alpine Permafrost—And How This Changes Everything in MY MEMORY's EYE, I Can Easily See the Mistake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

Case Study Skyway Mont Blanc, Courmayeur (IT)

Skyway Mont Blanc Case study Skyway Mont Blanc, Courmayeur (IT) Client: Funivie Monte Bianco AG, Courmayeur (IT) Architect: STUDIO PROGETTI Architect Carlo Cillara Rossi, Genua (IT) General contractor: Doppelmayr Italia GmbH, Lana Project completion: 2015 Products: FalZinc®, foldable Aluminium with a pre-weathered zinc surface Skyway Mont Blanc Mont Blanc, or ‘Monte Bianco’ in Italian, is situated between France and Italy and stands proud within The Graian Alps mountain range. Truly captivating, this majestic ‘White Mountain’ reaches 4,810 metres in height making it the highest peak in Europe. Mont Blanc has been casting a spell over people for hundreds of years with the first courageous mountaineers attempting to climb and conquer her as early as 1740. Today, cable cars can take you almost all of the way to the summit and Skyway Mont Blanc provides the latest and most innovative means of transport. Located above the village of Courmayeur in the independent region of Valle d‘Aosta in the Italian Alps Skyway Mont Blanc is as equally futuristic looking as the name suggests. Stunning architectural design combined with the unique flexibility and understated elegance of the application of FalZinc® foldable aluminium from Kalzip® harmonises and brings this design to reality. Fassade und Dach harmonieren in Aluminium Projekt der Superlative commences at the Pontal d‘Entrèves valley Skyway Mont Blanc was officially opened mid- station at 1,300 metres above sea level. From cabins have panoramic glazing and rotate 2015, after taking some five years to construct. here visitors are further transported up to 360° degrees whilst travelling and with a The project was developed, designed and 2,200 metres to the second station, Mont speed of 9 metres per second the cable car constructed by South Tyrolean company Fréty Pavilion, and then again to reach, to the journey takes just 19 minutes from start to Doppelmayr Italia GmbH and is operated highest station of Punta Helbronner at 3,500 finish. -

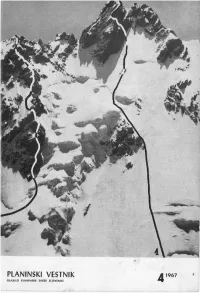

PV 1967 04.Pdf

poštnina plačana v gotovini VSEBINA: RAZMIŠLJANJA OB NAŠIH ODPRAVAH V KAVKAZ Ing. Pavle Šegula 145 KAVKAZ - MOST MED ALPAMI IN HIMALAJO EMO Janez Krušic 149 SLOVENSKO REBRO V SEVERNI STENI GESTOLE Celje Janez Krušic 157 SLOVENSKI STEBER V ULLU-AUSU Ing. Drago Zagorc 160 TIMOFEJEVA SMER V MIŽIRGIJU EMAJLIRNICA Janez Golob 161 METALNA INDUSTRIJA KAKO SE JE CVET SLOVENSKIH ALPINISTOV PRIVAJAL NA VIŠINO 5145 METROV ORODJARNA Boris Krivic 164 NJEGOV ZADNJI VZPON A. Kopinšek 168 IZDELUJE IN DOBAVLJA: K DISKUSIJI O NEKATERIH KRAŠKIH OBLIKAH VISO- KOGORSKEGA KRASA — frite z dodatki za izdelavo emajlov Dušan Novak 169 — emajlirano, pocinkano in alu posodo, sanitarno SEDEM DESETLETIJ PLANINSKEGA VESTNIKA in gospodinjsko opremo ter kovinsko embalažo (1895-1965) — toplotne naprave: radiatorje in kotle za cen- Evgen Lovšin 174 tralno in etažno ogrevanje GOZD JE NAŠ DOM 180 — odpreske in kolesa za motorna vozila ter od- DRUŠTVENE NOVICE 183 preske za rudarstvo ALPINISTIČNE NOVICE 184 — vse vrste orodij zo serijsko proizvodnjo: rezilna, IZ PLANINSKE LITERATURE 187 izsekovalna, vlečna, kombinirana in upogibna RAZGLED PO SVETU 188 orodja za predelavo pločevine, orodja za tlačni ANICA KUK liv in za proizvodnjo iz plastičnih mas, stekla Stanislav Gilič 191 in keramike NASLOVNA STRAN: — emajlira, pocinkuje in predeluje pločevine SEVERNO OSTENJE ULLU-AUS (4789 m) 1 - DIREKTNA SMER V SEVERNI STENI Tel.: 39-21 - Telegram: EMO-Celje - Telex: 0335-12 2 - SLOVENSKI STEBER - PRVENSTVENA SMER SEDEŽ: LJUBLJANA - VEVČE USTANOVLJENE LETA 1842 IZDELUJEJO SULFITNO CELULOZO I. a za vse vrste papirja PINOTAN - strojilni ekstrat BREZLESNI PAPIR za grafično in predelovalno in- dustrijo: za reprezentativne izdaje, umetniške slike, propagandne in turistične prospekte, za pisemski papir in kuverte najboljše kvalitete, za razne protokole, matične knjige, obrazce, -Planinski Vestnik« je glasilo Planinske zveze Slovenije / šolske zvezke in podobno Izdaja ga PZS - urejuje ga uredniški odbor. -

Mont Blanc Sur Sa Rive Gauche, Culminant À 4810 1971 N° 74.01 8 700 Ha Houches Mètres Et Constituant Le Toit De L’Europe Occidentale

MEDDE – ONF –IRSTEA CLPA CLPA - Notice par massif Notice sur les avalanches constatées et leur environnement, dans le massif du Mont-Blanc Document de synthèse accompagnant la carte et les fiches signalétiques de la CLPA N.B. : La définition du massif employée ici, est celle Chamonix AH68-69 utilisée par Météo France pour la prévision du risque AI68-69 d’avalanches (PRA). AJ67-68 AK67-68 Ce document consiste essentiellement en une relation, AK65-66-67-68 généralement à l’échelle d’un massif, des phénomènes Megève-Val d’avalanche historiques 2007 AL65-66-67 20 959 ha pour les zones étudiées par la Montjoie CLPA. Ce n’est pas une analyse de l’aléa ou du risque AM66-67 telles qu'elles figurent dans un Plan de Prévention des Risques (PPR). N.B. : la référence de chaque feuille comprend aussi son Par ailleurs, la rédaction relativement récente de ce année de diffusion. document peut expliquer l’absence de certaines parties du massif qui seront finalisées lors de leur révision La photo-interprétation n’a été que partiellement décennale. Toutes les mises à jour ultérieures seront complétée par l’analyse de terrain. consultables en ligne sur le site Internet : http://www.avalanches.fr 2. Caractéristiques géographiques 1. Historique de la réalisation de la CLPA sur le Présentation : secteur Le massif PRA (prévision du risque d’avalanches) du Mont-Blanc est situé en Haute Savoie et a globalement Les feuilles suivantes de la CLPA ont été publiées dans une forme de bande orientée du nord-est vers le sud- ce secteur : ouest. -

Pinnacle Club Jubilee Journal 1921-1971

© Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved PINNACLE CLUB JUBILEE JOURNAL 1921-1971 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL Fiftieth Anniversary Edition Published Edited by Gill Fuller No. 14 1969——70 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 1971 1921-1971 President: MRS. JANET ROGERS 8 The Penlee, Windsor Terrace, Penarth, Glamorganshire Vice-President: Miss MARGARET DARVALL The Coach House, Lyndhurst Terrace, London N.W.3 (Tel. 01-794 7133) Hon. Secretary: MRS. PAT DALEY 73 Selby Lane, Keyworth, Nottingham (Tel. 060-77 3334) Hon. Treasurer: MRS. ADA SHAW 25 Crowther Close, Beverley, Yorkshire (Tel. 0482 883826) Hon. Meets Secretary: Miss ANGELA FALLER 101 Woodland Hill, Whitkirk, Leeds 15 (Tel. 0532 648270) Hon Librarian: Miss BARBARA SPARK Highfield, College Road, Bangor, North Wales (Tel. Bangor 3330) Hon. Editor: Mrs. GILL FULLER Dog Bottom, Lee Mill Road, Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. Hon. Business Editor: Miss ANGELA KELLY 27 The Avenue, Muswell Hill, London N.10 (Tel. 01-883 9245) Hon. Hut Secretary: MRS. EVELYN LEECH Ty Gelan, Llansadwrn, Anglesey, (Tel. Beaumaris 287) Hon. Assistant Hut Secretary: Miss PEGGY WILD Plas Gwynant Adventure School, Nant Gwynant, Caernarvonshire (Tel.Beddgelert212) Committee: Miss S. CRISPIN Miss G. MOFFAT MRS. S ANGELL MRS. J. TAYLOR MRS. N. MORIN Hon. Auditor: Miss ANNETTE WILSON © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Page Our Fiftieth Birthday ...... ...... Dorothy Pilley Richards 5 Wheel Full Circle ...... ...... Gwen M offat ...... 8 Climbing in the A.C.T. ...... Kath Hoskins ...... 14 The Early Days ..... ...... ...... Trilby Wells ...... 17 The Other Side of the Circus .... -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

Mont Blanc, La Thuile, Italy Welcome

WINTER ACTIVITIES MONT BLANC, LA THUILE, ITALY WELCOME We are located in the Mont Blanc area of Italy in the rustic village of La Thuile (Valle D’Aosta) at an altitude of 1450 m Surrounded by majestic peaks and untouched nature, the region is easily accessible from Geneva, Turin and Milan and has plenty to offer visitors, whether winter sports activities, enjoying nature, historical sites, or simply shopping. CLASSICAL DOWNHILL SKIING / SNOWBOARDING SPORTS & OFF PISTE SKIING / HELISKIING OUTDOOR SNOWKITE CROSS COUNTRY SKIING / SNOW SHOEING ACTIVITIES WINTER WALKS DOG SLEIGHS LA THUILE. ITALY ALTERNATIVE SKIING LOCATIONS Classical Downhill Skiing Snowboarding Little known as a ski destination until hosting the 2016 Women’s World Ski Ski School Championship, La Thuile has 160 km of fantastic ski infrastructure which More information on classes is internationally connected to La Rosiere in France. and private lessons to children and adults: http://www.scuolascilathuile.it/ Ski in LA THUILE 74 pistes: 13 black, 32 red, 29 blue. Longest run: 11 km. Altitude range 2641 m – 1441 m Accessible with 1 ski pass through a single Gondola, 300 meters from Montana Lodge. Off Piste Skiing & Snowboarding Heli-skiing La Thuile offers a wide variety of off piste runs for those looking for a bit more adventure and solitude with nature. Some of the slopes like the famous “Defy 27” (reaching 72% gradient) are reachable from the Gondola/Chairlifts, while many more spectacular ones including Combe Varin (2620 m) , Pont Serrand (1609 m) or the more challenging trek from La Joux (1494 m) to Mt. Valaisan (2892 m) are reached by hiking (ski mountineering). -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

Views on the Mont-Blanc Mountain Range, the Aiguilles Rouges, the Fiz and the Aravis Massifs

Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix 190 place de l’église - 74400 Chamonix – France - Tél : + 33 (0)4 50 53 00 88 www.chamonix-guides.com - e-mail : [email protected] FAMILY TOUR DU MONT-BLANC – PRIVATE ZEC Duration: 6 days Level: The Tour du Mont-Blanc is an ideal and unmissable itinerary, a mythical loop that will allow you to discover the Alpine diversity of three countries and the rich heritage of these regions. Our ‘family’ trips are designed to allow young and old alike to share new discoveries and fun. Our choice of routes, as well as the contributions of our mountain leaders, endeavour to respond to the curiosity of all, fostering learning, an understanding of the mountain environment and the sharing of knowledge. One night in mountain hut will reinforce our immersion in the mountain environment! Luggage transportation during the tour by a taxi. Just bring the hiking necessities and fully enjoy the hike ! ITINERARY Day 1 : Les Houches - Chalet de Nant Borrant Our TMB starts from the the top of the Bellevue cable car, where we will have panoramic views on the Mont-Blanc mountain range, the Aiguilles Rouges, the Fiz and the Aravis massifs. On our way we cross the suspended bridge over Bionnassay torrent. Our descent leads us to Champel hamlet before reaching Les Contamines village. Our path continues to the bottom of the valley at Notre Dame de la Gorge. After one last hike up on the roman path we are reaching Nant Borrant mountain hut where we will spend the night (small dormitory). -

Chamonix to Zermatt

CHAMONIX TO ZERMATT About the Author Kev Reynolds first visited the Alps in the 1960s, and returned there on numerous occasions to walk, trek or climb, to lead mountain holidays, devise multi-day routes or to research a series of guidebooks covering the whole range. A freelance travel writer and lecturer, he has a long associa- tion with Cicerone Press which began with his first guidebook to Walks and Climbs in the Pyrenees. Published in 1978 it has grown through many editions and is still in print. He has also written more than a dozen books on Europe’s premier mountain range, a series of trekking guides to Nepal, a memoir covering some of his Himalayan journeys (Abode of the Gods) and a collection of short stories and anecdotes harvested from his 50 years of mountain activity (A Walk in the Clouds). Kev is a member of the Alpine Club and Austrian Alpine Club. He was made an honorary life member of the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild; SELVA (the Société d’Etudes de la Littérature de Voyage Anglophone), CHAMONIX TO ZERMATT and the British Association of International Mountain Leaders (BAIML). After a lifetime’s activity, his enthusiasm for the countryside in general, and mountains in particular, remains undiminished, and during the win- THE CLASSIC WALKER’S HAUTE ROUTE ter months he regularly travels throughout Britain and abroad to share that enthusiasm through his lectures. Check him out on www.kevreynolds.co.uk by Kev Reynolds Other Cicerone guides by the author 100 Hut Walks in the Alps Tour of the Oisans: GR54 Alpine Points -

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B.