Grassroots Development Journal of the Inter-American Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution

Mitchell Hamline School of Law Mitchell Hamline Open Access DRI Press DRI Projects 12-1-2020 Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution Howard Gadlin Nancy A. Welsh Follow this and additional works at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/dri_press Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Gadlin, Howard and Welsh, Nancy A., "Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution" (2020). DRI Press. 12. https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/dri_press/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the DRI Projects at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in DRI Press by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evolution of a Field: Personal Histories in Conflict Resolution Published by DRI Press, an imprint of the Dispute Resolution Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law Dispute Resolution Institute Mitchell Hamline School of Law 875 Summit Ave, St Paul, MN 55015 Tel. (651) 695-7676 © 2020 DRI Press. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020918154 ISBN: 978-1-7349562-0-7 Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota has been educating lawyers for more than 100 years and remains committed to innovation in responding to the changing legal market. Mitchell Hamline offers a rich curriculum in advocacy and problem solving. The law school’s Dispute Resolution Insti- tute, consistently ranked in the top dispute resolution programs by U.S. News & World Report, is committed to advancing the theory and practice of conflict resolution, nationally and inter- nationally, through scholarship and applied practice projects. -

Mar 07, 2021 Issue 2

CampusMONDAY, MARCH 8, 2021 / VOLUME 148, ISSUE 2 Times SERVING THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER COMMUNITY SINCE 1873 / campustimes.org URAC Holds Protest During Mangelsdorf Event, Demands Action By Henry Litzky and Haven Worley PHOTO EDITOR and NEWS EDITOR On Thursday, the UR Abolition Coalition (URAC) staged a protest at the in-person Casual Conversa- tions with President Mangelsdorf event. During the event, students repeated their de- mands for changes to the Department of Public Safety (DPS) to Mangelsdorf directly. This move follows last semester’s overnight occu- pation of the DPS parking lot where URAC protes- tors voiced their demands to University President Sarah Manglesdorf and DPS chief Mark Fischer, who promised further discussion. “[President Manglesdorf] had promised us that night [...] that she would be starting to actually have progress with this mental health task force to institute Daniel’s [Law] on campus, and ensure that cops [...] and campus police do not respond to mental health calls on this campus,” URAC orga- nizer and senior Antoinette Nguyen said. “Howev- er, there’s been no update regarding that.” The protest began at the steps of Rush Rhees Li- brary, where many of their actions have started in the past. At around 4:30 p.m., organizers went over the plans to the group of roughly 30 people around the steps. HENRY LITSKY / PHOTO EDITOR They departed the steps at 4:36 p.m. and walked son Commons and then Rush Rhees, armed with cially for admin,” URAC member and junior Katie down Eastman Quad chanting, “What do we want? hundreds of paper flyers that listed The Students’ Hardin said. -

Book Proposal 3

Rock and Roll has Tender Moments too... ! Photographs by Chalkie Davies 1973-1988 ! For as long as I can remember people have suggested that I write a book, citing both my exploits in Rock and Roll from 1973-1988 and my story telling abilities. After all, with my position as staff photographer on the NME and later The Face and Arena, I collected pop stars like others collected stamps, I was not happy until I had photographed everyone who interested me. However, given that the access I had to my friends and clients was often unlimited and 24/7 I did not feel it was fair to them that I should write it all down. I refused all offers. Then in 2010 I was approached by the National Museum of Wales, they wanted to put on a retrospective of my work, this gave me a special opportunity. In 1988 I gave up Rock and Roll, I no longer enjoyed the music and, quite simply, too many of my friends had died, I feared I might be next. So I put all of my negatives into storage at a friends Studio and decided that maybe 25 years later the images you see here might be of some cultural significance, that they might be seen as more than just pictures of Rock Stars, Pop Bands and Punks. That they even might be worthy of a Museum. So when the Museum approached me three years ago with the idea of a large six month Retrospective in 2015 I agreed, and thought of doing the usual thing and making a Catalogue. -

Final Nominations List the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences, Inc

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS LIST THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. Final Nominations List 63rd Annual GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year September 1, 2019 through August 31, 2020 Note: More or less than 5 nominations in a category is the result of ties. General Field Category 1 8. SAVAGE Record Of The Year Megan Thee Stallion Featuring Beyoncé Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) Beyoncé & J. White Did It, producers; Eddie “eMIX” and/or Mixer(s) and mastering engineer(s), if other than the artist. Hernández, Shawn "Source" Jarrett, Jaycen Joshua & Stuart White, engineers/mixers; Colin Leonard, mastering 1. BLACK PARADE engineer Beyoncé Beyoncé & Derek Dixie, producers; Stuart White, engineer/mixer; Colin Leonard, mastering engineer 2. COLORS Black Pumas Adrian Quesada, producer; Adrian Quesada, engineer/mixer; JJ Golden, mastering engineer 3. ROCKSTAR DaBaby Featuring Roddy Ricch SethinTheKitchen, producer; Derek "MixedByAli" Ali, Chris Dennis, Liz Robson & Chris West, engineers/mixers; Glenn A Tabor III, mastering engineer 4. SAY SO Doja Cat Tyson Trax, producer; Clint Gibbs & Kalani Thompson, engineers/mixers; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer 5. EVERYTHING I WANTED Billie Eilish Finneas O'Connell, producer; Rob Kinelski & Finneas O'Connell, engineers/mixers; John Greenham, mastering engineer 6. DON'T START NOW Dua Lipa Caroline Ailin & Ian Kirkpatrick, producers; Josh Gudwin, Drew Jurecka & Ian Kirkpatrick, engineers/mixers; Chris Gehringer, mastering engineer 7. CIRCLES Post Malone Louis Bell, Frank Dukes & Post Malone, producers; Louis Bell & Manny Marroquin, engineers/mixers; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer © The Recording Academy 2020 - all rights reserved 1 Not for copy or distribution 63rd Finals - Press List General Field Category 2 8. -

August 2020 Issue

THE HARBINGER Empowering young minds through information Miami Lakes Educational Center August 2020 ~ Vol. XXII No. 1 5780 NW 158th St Miami Lakes, FL Miami Week Of Welcome: “Ready, Set, MSO!” waking up at their usual time to “I expect the first week of time to begin the process of trict officials have also recom- By Aileen Delgado reunite with their classmates; to be about situating ourselves and aggregating the necessary data. mended that students wear their @aileenedu instead, high school will begin working on being able to com- “There continue to be uniforms at home, to achieve After months of un- at 8:30, an hour and ten min- municate smoothly with teachers. challenges for all of us. Students, “a greater sense of normalcy.” certainty, a surge in COVID-19 utes later. Instead of navigating It can get hard especially with parents, teachers, and district Regardless of how much infections and public debates, through the school campus, to teachers who may not be techno- personnel would all like to feel teachers and district officials push Miami-Dade County Public the right classroom in the cor- logically inclined,” she continued. 100 percent secure as we move for a smooth opening of schools, Schools (MDCPS) will begin rect building, Jaguars will open With an updated bell forward, but we are utilizing a it will feel far from normal. the 2021 school year online. up a laptop and click to attend schedule and an unfamiliar on- technological medium to deliver “The past several months After days of parent in- a scheduled virtual meeting. -

Art Exhibit Portrays Struggles, Emphasizes Hope Workshop

THE Vol. 103 No. 2 IONIAN The Official Student-Run Newspaper of Iona College February 25 - March 9, 2021 Like Ionian Newspaper on Facebook www.TheIonian.org Follow us on Twitter @IonianNewspaper News...................2 Black History Art exhibit portrays struggles, emphasizes Month.................3 hope Features...............5 By: Margaret Dougherty Managing Editor difficulties faced today both personally and Opinion................7 by society as a whole. The artists each used WHERE TO START their unique medium – such as paintings, Arts.....................8 collages, sculptures and photography – to illuminate some of these issues and attempt Sports...............10 to reach an understanding of one another’s struggles. Many of the recurring themes in the Ways to limit art centered around the pandemic, including screen time struggles with mental health, economic Features & Lifestyle uncertainty and food insecurity. However, the most dominant theme of the exhibit is the Editor Aliyah discrimination and marginalization faced by Rodriguez explores people of color. Many of the artists were inspired by the FEATURES ways to give your growth of the Black Lives Matter movement eyes a break. this past year. Janet Smith Castronuovo created a mixed media collage entitled ‘We Are: The “Humanity Arises and Takes to the Street” Brooklyn Saints’ to represent the many people who marched for Black lives in 2020. In the collage, a is an emotional masked protester raises their hands while a documentary on red circle around their head creates a target football, community mark. Behind the protester is a collection of newspaper clippings and powerful phrases This documentary that were commonly heard in 2020, such as focuses on more “Hands up, don’t shoot,” “I can’t breathe” than just the game of and “Stop the spread.” Although last year was football. -

Power Failure Leaves Rice in the Dark for Four Hours Outage Reveals Inadequacies of Campus Emergency Lighting Systems

SINCE 1916 VOLUME 76, NO WE NEVER GUARANTEED A SWIMSUIT ISSUE FEBRUARY 10, 1989 Power failure leaves Rice in the dark for four hours Outage reveals inadequacies of campus emergency lighting systems when it did go out this time, they by Anu Bajaj were too busy taking aire of other stuff, so it was just,better to let us sit A power outage Monday, Febru- it out," she said. ary 6, left the entire campus dark for Director of the Physical Plant Ed four hours and raised questions Samfield said they have the capacity about the preparedness of the uni- to use the cogenerator to power part versity for emergency situations. of the university. However, the co- Although power has been restored generator also lost power. to the entire campus, the cause of the "The cogenerator has the capac- outage is still unknown. ity to generate its own electricity, but No injuries occurred during the it went out, too. It's not meant to blackout, but several buildings on replace Houston Lighting and Power campus were left without emer- but to supplement it If we had been % gency lighting and the Rice Univer- unable to restore HL&P power, we sity Police Department had no emer- could have turned on power to a gency power. limited area of the university," he Rice University Police Depart- said. ment without generator Fondren Library—insufficient Chief of RUPD Mary Voswinkel emergency lighting said RUPD had no problems doing Because of the power outage its job despite being left without Fondren Library closed early. -

College Voice Vol. 35 No. 11

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2010-2011 Student Newspapers 2-7-2011 College Voice Vol. 35 No. 11 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2010_2011 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 35 No. 11" (2011). 2010-2011. 9. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2010_2011/9 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2010-2011 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. MONDAY FEBRUARY 7 2011 VOLUME -J<er l5SUE II the balcony playing cards , Monday. March 3. 1919: "ZZ .• Runty. Jess and I spent all Our time out (J(\ . t \.>as a peach of a day." - Diary of Mildred Howard Meet Connecticut College's first graduating class of 1919. For more stories and photos from our first decade. see page 2. True Grit Women's Basketball fights through off-court issues to claim first NESCACwin in three years MIKE FLINT After starting off the month of SPORTS EDITOR January so well with consecutive On Saturday, women's bas- victories against New York City ketball defeated Wesleyan 49-42 College of Technology, NYU, at home, securing the Camels' Eastern Nazarene College and first NESCAC victory since the Johnson & Wales, by the 22nd 2007 -2008 season. Such an ac- the Camels had officially slipped complishment is something to on the NESCAC ice. Conn had celebrate no matter the circum- lost four games in a row-all to stances, but considering the kind conference opponents-and al- of season-let alone the kind of though the team was playing well, the lack of success in league was CECILIA BROWN I STAFF month-women's hasketball has been having, the win over Wes- growing more and more frustrat- leyan was a well-deserved story- ing by the day. -

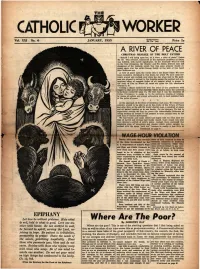

·Wh-Ere Are the Poor? Is Evil, Hold to What Is Good

' CATHOLIC WORKER Subacr1ption1 Vol. XXI No. 6 J~ARY, 1955 25c Per Vear Price le A RIVER OF. PEACE - CHRISTMAS MESSAGE OF THE HOLY FATHER "Behold I will bring upon her, as ;t were', a river of peace" (Isaias 66, 12). This promise, announced in the messianic prophecy of Isaias, was fulfilled, with mystic significance, by the Incarnate Word of God in the New Jerusalem, the Church: and We desire, beloved sons and daughters of the Catholic world, that this same promise should re sound again over the entire human f1;1mily as the wish of Our heart this Chrlstmas eve. A river of peace upon the world: this is the desire which We have most constantly cherished in Our heart, for. which We have most fer vently prayed and worked, ever since the day when God in His good ness was pleased to entrust to Our humble person the exalted and awe inspiring office of common father of all peoples which is proper to the vicar of Him to Whom all races are given for His inheritance -- (Psalms 2, 8). Casting a glance backwards over the years of Our pontificate with regard to that ,part of Our .mandate which derives from the universal fa therhood conferred upon Us, We feel that it was the intention of Divine Providence to assign to Us the particular mission. of helping, by means of patient and almost exhausting toil, to lead mankind back to the paths of peace. * * * At the approach of the feast of Christmas each year, We would have ardently wished to ·be able to go to the cradle of the Prince of Peace and offer Him, as the gift He would cherish most, a mankind at peace and all united together as in one family. -

The Mckinley Times, Student Newspaper VIII

THE MCKINLEY TIMES February 2021 Serving the McKinley Community Since 2020 Volume VIII Donald Trump Stop Motion Animation Impeachment Trial by Jacob M. Please note, this article was written before the trial. When you are doing stop motion, you can take pictures and make it look like by Juliet S. the toys or anything you are using is moving. You have to take pictures of On January 20, we welcomed new presi- International Day: What Will their actions. It will seem like it is easy, dent, Joe Biden, and Vice President Ka- It Look Like Online? but it is harder than it looks. It takes time mala Harris into office. But scrutiny does to put them in place and do whatever not seem to be over for former president by Molly L. you want with them. You can make a Donald Trump. movie, and, if you have iMovie, you can McKinley Elementary School has a lot send it to iMovie and add noise. Trump is the first president to have been of yearly events and traditions. One impeached twice. In his first trial, he was event you may remember from past The Super Bowl acquitted, meaning that he had an im- years is International Day. On Interna- peachment trial, but was ultimately not tional Day, we can learn about other cul- by Jonah C. removed from office. As for what will tures and their traditions. Because of the happen in this trial, we don’t know yet. pandemic, this event will be online. Even The Super Bowl is the most popular so, the PTA has some amazing plans to sports game in America. -

Daily Eastern News: January 21, 2021

Eastern Illinois University The Keep January 2021 1-21-2021 Daily Eastern News: January 21, 2021 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2021_jan Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: January 21, 2021" (2021). January. 8. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2021_jan/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the 2021 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in January by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PEACE TALKS OVC STANDINGS UPDATE A virtual conversation about the concept of The Belmont men's basketball peace-will be held Thurs<1:ay afternoon. team leads the OVC while Eastern PAGE 5 is tied for seventh place. PAGE 8 =~ E-4 AILY ASTERN EWS Thursday, January 21, 2021 "TELL THE .RUTH AND DON'T BE FRAID" VOL. 105 I NO. 80 Students Inauguration Day display share their thoughts on inaugliration By Julie Zaborowski Staff Reporter I @DEN_news Joseph R. Biden, Jr. was sworn in as the 46th President of the United States on Wednesday. This year's historical inauguration has sparked much debate and left many with questions as to what will come next. With the new vice president, Kamala Har ris, being the fiTSt woman and person of Black and South Asian descent to hold the of fice, the country continuing its combat with COVID-19 and citizens protesting for causes on both the left and right side of politics, stu dents have mixed opinions on the swearing in of the 46th president of the United States. -

Cynthia Erivo, Chloe X Halle, and Trevor Noah Wear Tiffany & Co. at the 63Rd Annual Grammy Awards

Cynthia Erivo, Chloe x Halle, and Trevor Noah Wear Tiffany & Co. at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards | 1 (Los Angeles, CA): Nominated for Best Song Written For Visual Media for “Stand Up” from the film Harriet, Cynthia Erivo wore iconic Tiffany & Co. Schlumberger® Mellon diamond earclips at this year’s Grammy Awards. She completed her look with a Tiffany & Co. Curb Link Bracelet and a selection of Tiffany & Co. Schlumberger® and Tiffany T T1 diamond rings. Three-time nominees, including for Best Progressive R&B Album for Ungodly Hour, Chloe x Halle each donned Tiffany & Co. Chloe Bailey appeared wardrobed in Tiffany HardWear double long link earrings, along with a Tiffany T T1 bangle, Tiffany HardWear link bracelet, and a Tiffany Victoria® diamond ring. Meanwhile, Halle Bailey wore Tiffany Victoria® mixed cluster drop earrings and bracelet, with a selection of diamond Tiffany T T1 bangles and rings. The night’s host, Trevor Noah wore a dazzling Tiffany & Co. Schlumberger® Apollo brooch. Cynthia Erivo, Chloe x Halle, and Trevor Noah Wear Tiffany & Co. at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards | 2 Cynthia Erivo, Chloe x Halle, and Trevor Noah Wear Tiffany & Co. at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards | 3 Cynthia Erivo, Chloe x Halle, and Trevor Noah Wear Tiffany & Co. at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards | 4 Cynthia Erivo, Chloe x Halle, and Trevor Noah Wear Tiffany & Co. at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards | 5 Jewerly Details: Cynthia Erivo, Chloe x Halle, and Trevor Noah Wear Tiffany & Co. at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards | 6 About Tiffany & Co. TIFFANY & CO., founded in New York City in 1837 by Charles Lewis Tiffany, is a global luxury jeweler synonymous with elegance, innovative design, fine craftsmanship and creative excellence.