Historical Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inkerman Lodge Farm Hungarton, Leicestershire

INKERMAN LODGE FARM HUNGARTON, LEICESTERSHIRE Sales ● Lettings ● Surveys ● Mortgages Market Harborough 15.3 miles l Melton Mowbray 9.6 miles l Uppingham 13.5 miles l Oakham 12.3 miles Sales ● Lettings ● Surveys ● Mortgages Non -printing text please ignore Inkerman Lodge Farm OUTSIDE Hungarton There are formal gardens to the front and rear of the house designed to require minimal maintenance. The Leicestershire rear gardens are sheltered, laid to lawn and enjoys a pond with stunning bucolic views beyond. A paddock is Guide Price £1,800,000 fenced with water connected. There are no public rights A handsome, unlisted country home nestled of way over the paddock. peacefully between Cold Newton and Lowesby in To one end of the home office is a store room a triple a picturesque setting with far reaching garage with a substantial parking area. Behind the uninterrupted countryside views. garaging is a large portal framed barn with a lean-to hay barn and another concrete hard standing area. Entrance hall l Four reception rooms l Kitchen and The p ermanent pastureland which is in one block is principally located behind the property with 15 acres breakfast room Five bedrooms Three bathrooms l l l located at the front and is divided into a number of Triple garaging l Self-contained annex l Workshop l enclosures with water and three further ponds . Basic Payments entitlements are included within the sale which Two barns Approx. 70 acres l l the vendor will endeavour to transfer to the purchaser. The vendor will keep the 2018 Basic Payment. The ACCOMMODATION annual grass keeping agreement is renewable in April of Inkerman Lodge is believed to have originated around 1750 each year. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE. -

How to See Your Doctor

L H LATHA M M P HOUS E M E D I C A L P R A C T I C E Sage Cross Street, Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, LE13 1NX Tel: 01664 503000 Fax: 01664 501825 Asfordby Branch Surgery Regency Road, Asfordby, Leicestershire, LE14 3YL Tel: 01664 503006 Fax: 01664 501825 www.lhmp.co.uk OUT OF HOURS: 0845 045041 NHS Direct 0845 4647 www.nhsdirect.uk *Please see overleaf for Area covered by Latham House Medical Practice Latham House Medical Practice is the largest single group practice in the country. We are the only practice serving the market town of Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, Leicester and the surrounding area. Latham House Medical Practice was established in 1931, it's aim is to provide as many services as possible, by a wide range of clinicians, to their patients, from within their premises. The Practice encourages their clinicians to have specialist areas of interest and we still believe the best services we can offer to patients is by doctors holding registered lists, so that patients can forge long lasting relationships with the doctor of their choice. The Latham House Medical Practice is open from 8.30am to 6.30pm. A duty doctor is on site 8am – 8.30am and 6pm – 6.30pm. Appointments are available at various times between: 8.30 am - 5.30 pm at the main site at Melton Mowbray and between 9.00 am – 10.30 am at the Asfordby branch surgery. Extended hours – appointments are also available Mondays 7.50am – 8.00am and 6.30pm – 7.00pm, Thursdays 6.30pm – 7.00pm. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

Allexton 1994 Laughton Arnesby 1987 * Leire Ashby Parva 1987

HARBOROUGH DISTRICT COUNCIL : CONSERVATION AREA STATEMENTS Allexton 1994 Laughton 1975 Arnesby 1987 * Leire 1975 Ashby Parva 1987 Lowesby 1975 Billesdon 1974 Lubenham 1975 Bitteswell 1972 * Lutterworth 1972 Blaston 1975 ** Market 1969 Harborough Bringhurst 1972 * Medbourne 1973 Bruntingthorpe 1973 Nevill Holt 1974 Burton Overy 1974 North Kilworth 1972 Carlton Curlieu 1994 Owston 1975 Catthorpe 1975 Peatling Parva 1976 Church Langton 1994 Rolleston 1994 Claybrooke Parva 1987 * Saddington 1975 Drayton 1975 Scraptoft 1994 East Langton 1972 Shawell 1975 East Norton 1994 * Shearsby 1975 Foxton 1975 * Skeffington 1975 Gaulby 1994 * Slawston 1973 Great Bowden 1974 Smeeton Westerby 1975 Great Easton 1973 Stoughton 1987 Gumley 1976 Swinford 1975 Hallaton 1973 * Theddingworth 1975 Horninghold 1973 Thurnby 1977 Houghton-on-the-Hill 1973 * Tilton-on-the-Hill 1975 Hungarton 1975 * Tugby 1975 Husbands Bosworth 1987 * Tur Langton 1975 Illston-on-the-Hill 1977 Ullesthorpe 1978 Keyham 1975 Walton 1975 * Kibworth Beauchamp 1982 * Willoughby 1975 Waterleys * Kibworth Harcourt 1982 Grand Union 2000 Canal Kimcote 1977 (Foxton Locks) Kings Norton 1994 (Market Harborough Loddington 2006 Canal Basin) Supplementary Planning Guidance , Issue 1 - September 2001 Produced by the Planning Policy and Conservation Group HARBOROUGH DISTRICT COUNCIL : CONSERVATION AREA STATEMENTS Designated Designated Allexton 1994 Laughton 1975 Arnesby 1987 * Leire 1975 Ashby Parva 1987 Lowesby 1975 Billesdon 1974 Lubenham 1975 Bitteswell 1972 * Lutterworth 1972 Blaston 1975 ** Market -

THE LEICESTERSHIRE Archleological SOCIETY 1954

THE LEICESTERSHIRE ARCHlEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 1954 President Lt.-Col. Sir Robert Martin, C.M.G., D.L., M.A. Vice-Presidents Kathleen, Duchess of Rutland The Hon. Lady Martin The Right Rev. The Lord Bishop of Leicester, D.D. The Right Hon. Lord Braye The High Sheriff of Leicestershire The Right Worshipful The Lord Mayor of Leicester The Very Rev. H. A. Jones, B.Sc., Provost of Manchester Sir William Brockington, C.B.E., M.A. Colin D. B. Ellis, Esq., M.C., M.A., F.S.A. Albert Herbert, Esq., F.R.I.B.A., F.S.A. Capt. L. H. Irvine, M.B.E., M.A. Victor Pochin, Esq., M.A., D.L. Walter Brand; Esq., F.R.I.B.A. A. Bernard Clarke, Esq. Levi Fox, Esq., M.A., F.S.A. W. G. Hoskins, Esq., M.A., Ph.D. Miss K. M. Kenyon, M.A., F.S.A. Officers Hon. Secretary: David T .-D. Clarke, Esq., M.A. Hon. Treasurer: C. L. Wykes, Esq., F.C.A. Hon. Auditor: Percy Russell, Esq., F.C.A. Hon. Editors: Professor J. Simmons, M.A. Norman Scarfe, Esq., M.A. Hon. Librarian: G. H. Martin, Esq., M.A. Trustees of the Leicestershire Archa1ological Society Albert Herbert, Esq., F.R.I.B.A., F.S.A. Lt.-Col. Sir Robert Martin, C.M.G., D.L., M.A. 8 LEICESTERSHIRE ARCH£0LOGICAL SOCIETY Trustees of the Leicestershire Archamlogical Research Fund Colin D. B. Ellis, Esq., M.C., M.A., F.S.A. A. H. Leavesley, Esq. Anthony Herbert, Esq., A.R.I.B.A. -

Hungarton Parish Walks

3 6 /4km (4 miles), 4 Continue along the drive. walk 2:allow 2 hours. Good views of Hungarton can be seen in the distance. Hungarton Undulating countryside, muddy in places. Just past the Lodge Gatehouse bear right following the Take the bridleway out of Church Lane, past the farm waymarkers across two large fields, leading back into This leaflet is one of a series produced to promote buildings following the track through the Hungarton Church lane. circular walking throughout the county. You can obtain Hungarton Spinney. After the gate bear right and keep to the As you descend back to the village you can clearly see others in the series by visiting your local library or track with the hedge boundary on your left. the ridge-and-furrow pattern left by medieval ploughing Tourist Information Centre. You can also order them by Then, go straight across three more fields following methods. The up and down ploughing of long narrow phone or from our website. the waymarkers to reach Hungarton Road. strips, with a certain type of plough, threw the soil circular 1 Turn right and continue along the road to a towards the centre of the strip, so producing a high ridge. walks T-junction. Then turn left over the cattle grid. Much ridge-and-furrow disappeared with the intense 2 ploughing during the Second World War, however a good 3 1 Leave the road taking the bridleway on your right. 1 5 ⁄4 kms/3 ⁄2 miles Slowly descend as views of rolling hills and village deal remains in Leicestershire. -

Accompanying Note

Rural Economy Planning Toolkit Companion Document Instructions for Using the Toolkit Useful Context Information Produced by: Funded by: Rural Economic Development Planning Toolkit This document explains how to use the toolkit in greater detail and sets out some of the broader context relevant to the development of the toolkit. Its sections are: Instructions for Using the Toolkit Economic Development Context The Emerging National Framework for Planning and Development The assessment of planning applications for rural economic development: designated sites and key issues for Leicestershire authorities What makes a good rural economic development planning proposal? Case Studies Parish Broadband Speeds The Distribution and Contribution of Rural Estates within Leicestershire Attractions in Leicester and Leicestershire Instructions - Using the Toolkit The toolkit is in the form of an interactive PDF document. Most of the text is locked, and you cannot change it. Throughout the toolkit, though, comments, information and responses are asked for, and boxes you can type in are provided. You are also asked to select 'traffic lights' – red, amber or green. It is important to understand that, if you start with a blank copy of the toolkit, the first thing you should do is save it with a different name using the 'Save as Copy' command in Acrobat Reader. This means you have now created a version of the toolkit for the particular project you are working on, and still have the blank copy of the toolkit for another time. Let's assume you have saved your copy of the PDF file as 'Project.pdf' – every time you save again you will save all of the additions and traffic light choices you have made. -

High Leicestershire

Landscape Character Area Harborough District Landscape Character Assessment High Leicestershire High Leicestershire Landscape Character Area Key Characteristics Topography Tilton on the Hill • Steep undulating hills The topography of High Leicestershire is its most Scraptoft • High concentration of woodland defining feature. The steeply sloping valleys and Bushby • Parkland areas with narrow gated roads Houghton on the Hill broad ridges were created by fluvio-glacial influences Leicester Thurnby • Rural area with a mix of arable farming on and water courses that flowed across the area. The lowlands and pasture on hillsides central area of High Leicestershire reaches 210m East Norton • Scattering of traditional villages and hamlets AOD beside Tilton on the Hill, and falls to below High Leicestershire through the area 100m AOD along the western edge of Leicester. The • Encroachment of Leicester to the west of the topography generally radiates out and down from this Great Glen area high point adjacent to Tilton on the Hill into the valleys of the adjoining character areas and Leicester city. General Description Geology Fleckney Kibworth The predominantly rural character area comprises Broughton Astley Medbourne undulating fields with a mix of pasture on the higher The main geology grouping of High Leicestershire is sloping land and arable farming on the lower, Jurassic Lower Lias. Foxton flatter land. Fields are divided by well established Upper Soar Welland Valley hedgerows, with occasional mature hedgerow Vegetation Ullesthorpe Lutterworth Lowlands trees. A network of narrow country lanes, tracks and Lubenham Market Harborough footpaths connect across the landscape interspersed The numerous woodlands which stretch across the by small thickets, copses and woodlands. -

The Leicestershire Archjeological and Historical Society 1961-2

THE LEICESTERSHIRE ARCHJEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1961-2 President Lieut.-Col. Sir Robert Martin, C.M.G., D.L., T .D., LLD., M.A. (Deceased 13 1une 1961) Colin D. B. Ellis, Esq., C.B.E., M.C., M .A., F.S.A. (Elected 29 September 1961) * Vice-Presidents Kathleen, Duchess of Rutland The Hon. Lady Martin The Right Revd. The Lord Bishop of Leicester, D.D. The High Sheriff of Leicestershire The Right Worshipful The Lord Mayor of Leicester The Very Revd. H. A. Jones,, B.Sc., Dean of Manchester Albert Herbert, Esq., F.R.I.B.A., F.S.A. Victor Po:::hin, Esq., C.B.E., M.A., D.L., J.P. A. Bernard Clarke, Esq. Levi Fox, Esq., M.A., F.S.A. W. G. Hoskins, Esq., M.A., Ph.D. Miss K. M. Kenyon, C.B.E., M.A., D.Lit., F.B.A., F.S.A. * Officers Hon. Secretary: David T-D. Clarke, Esq., M.A., F.M.A. Hon. Treasurer: C. L. Wykes, Esq., F.C.A. Hon. Auditor: Lieut.-Col. G. L. Aspell, T.D., D.L., F.C.A. Hon. Editor : Professor J. Simmons, M .A., F.R.Hist.S., F.R.S.L. Hon. Librarian: G. H. Martin, Esq., M.A., D.Phil., F.R.Hist.S. * Trustees of the Leicestershire Archawlogical and Historical Society J. E. Brownlow, Esq. Colin D. B. Ellis, Esq., C.B.E., M.C., M.A., F.S.A. Albert Herbert, Esq., F .R.I.B.A., F.S.A. J. N. Pickard, Esq., J.P. -

The Archjeological Leicestershire and Historical Society

THE LEICESTERSHIRE ARCHJEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1966-67 President Profe1;sor Jack Simmons, M.A., F.R.HIST.S., F.R.S.L. * President-Emeritus Colin D. B. Ellis, Esq., C.B.E., M.C., M.A., F .S.A, * Vice-Presidents Kathleen, Duchess of Rutland The Hon. Lady Martin The Right Reverend ,The Lord Bishop of Leicester, D.D. The High Sheriff of Leicestershire The Right Worshipful The Lord Mayor of Leicester The Very Reverend H. A. Jones, B.SC. Victor Pochin, Esq., C.B.E., M.A., D.L., J.P. A. Bernard Clarke,. Esq. Levi Fox, Esq., M.A., F.S.A. Professor W. G. Hoskins, M.A., M.SC., PH.D. Miss K. M. Kenyon, C.B.E., M.A., D.LITT., F.B.A., F.S.A.. Mrs. F. E. Skillington * Officers Hon. Secretaries: James Crompton, Esq., M.A., B.LITT., F.R.HIST.S., F.S.A, (Minutes) Miss Mollie P. Rippin, B.A. (General) Miss Winifred A. G. Herrington (Excursions) Hon. Treasurer: C. L. Wykes, Esq., F.C.A. Hon. Auditor : Lieut.-Col. G. L. Aspell, T.D., D.L., F.C.A. Hon. Editor: James Crompton, Esq., M.A., B.LITT., F.R.HIST.S., F.S.A. Hon. Librarian: F. S. Cheney, Esq. * Trustees of the Leicestershire Archceological and Historical Society J. E. Brownlow, Esq. Colin D. B. Ellis, Esq., C.B.E., M.C., M.A., F.S.A.• J. N. Pickard, Esq., J.P. J. R. Webster, Esq. C. L . Wykes, Esq., F.C.A. * Trustees of the Leicestershire Archceological Research Fund 0 . -

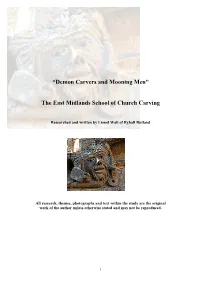

Demon Carvers and Mooning Men V4

“Demon Carvers and Mooning Men” The East Midlands School of Church Carving Researched and written by Lionel Wall of Ryhall Rutland All research, themes, photographs and text within the study are the original work of the author unless otherwise stated and may not be reproduced. 1 Contents Churches included in this Study……………………………………………………………………...3 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Summary of Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………….6 Ryhall and Oakham – the Quest Begins……………………………………………………………..7 The Mooning Men…………………………………………………………………………………...9 Terminology………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Dating the Work…………………….……………………………………………………………….11 Subject Matter……………………………………………………………………………………….12 The Significance of the Mooning Men…………………….………………………………………..14 Those Naughty Stonemasons……………………….……………………………………………….15 What were the Friezes for?.................................................................................................................17 Common Themes……………………………………………………………………………………21 Four Carvers…………………………………………………………………………………………24 The King of the Gargoyle…………………………………………………………………………...33 The Shop Work Issue……………………………………………………………………………….36 Demons & Gargoyles……………………………………………………………………………….37 Setting the Boundaries………………………………………………………………………………38 The Mooning Gargoyles…………………………………………………………………………….40 Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………….41 Church Friezes of the Mooning Men Guild • Ryhall…………………………………………………………43 • Oakham……………………………………………………….47 • Cottesmore……………………………………………………50 • Buckminster…………………………………………………..51