In Defence of Story-Telling Penultimate Version, Forthcoming in Studies In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"We Are the Kickers!" the Milwaukee

WE ARE THE KICKERS! The Milwaukee Kickers Story Chapter 1: “Realizing a Dream” The Wisconsin Soccer Association began a youth soccer program in 1962 with the Milwaukee County Parks & Recreation Department, which, by 1968, had become the third largest participation sport in the park system. In 1970, it moved up to second largest. Because the league program was basically ethnic-oriented, it became evident in 1968 to several people deeply involved in Milwaukee area soccer clubs that a new club needed to be formed to accommodate the growing number of American kids enjoying the game. Recognizing the lack of opportunity for the American player in an almost totally ethnic controlled sport, the 12 initiators wanted to develop the sport in a unique way to become a “traditional American” sport: to give everyone a place and a chance to play, boys and girls alike; to provide good coaching and stable administration; and, most importantly, to develop FAMILY INVOLVEMENT, which, in turn, would provide a strong volunteer base from which to operate the club. After much soul searching, these people left their respective clubs and founded the Milwaukee Kickers in November, 1968. Using the slogan, “American Soccer is Our Goal”, and choosing red and gray as club colors, the twelve Founders were: Carol and Lorenzo Draghicchio, Lew and Louise Dray, Dorothy and Frank Kral, Aleks and Helga Nikolic, Irene and Milan Nikolic, Elfriede and Sirous Samy . The fledgling club operated literally on a shoestring, relying almost entirely on car washes, rummage sales, newspaper drives and merchandise sales to finance the operation. The first adult squads competed in January, 1969, in the Indoor Season of the WSA at the Milwaukee Auditorium. -

Rushing Union Elections: Protecting the Interests of Big Labor at the Expense of Workers’ Free Choice

RUSHING UNION ELECTIONS: PROTECTING THE INTERESTS OF BIG LABOR AT THE EXPENSE OF WORKERS’ FREE CHOICE HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND THE WORKFORCE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD IN WASHINGTON, DC, JULY 7, 2011 Serial No. 112–31 Printed for the use of the Committee on Education and the Workforce ( Available via the World Wide Web: www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/committee.action?chamber=house&committee=education or Committee address: http://edworkforce.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 67–240 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND THE WORKFORCE JOHN KLINE, Minnesota, Chairman Thomas E. Petri, Wisconsin George Miller, California, Howard P. ‘‘Buck’’ McKeon, California Senior Democratic Member Judy Biggert, Illinois Dale E. Kildee, Michigan Todd Russell Platts, Pennsylvania Donald M. Payne, New Jersey Joe Wilson, South Carolina Robert E. Andrews, New Jersey Virginia Foxx, North Carolina Robert C. ‘‘Bobby’’ Scott, Virginia Bob Goodlatte, Virginia Lynn C. Woolsey, California Duncan Hunter, California Rube´n Hinojosa, Texas David P. Roe, Tennessee Carolyn McCarthy, New York Glenn Thompson, Pennsylvania John F. Tierney, Massachusetts Tim Walberg, Michigan Dennis J. Kucinich, Ohio Scott DesJarlais, Tennessee David Wu, Oregon Richard L. Hanna, New York Rush D. Holt, New Jersey Todd Rokita, Indiana Susan A. Davis, California Larry Bucshon, Indiana Rau´ l M. Grijalva, Arizona Trey Gowdy, South Carolina Timothy H. -

2008-09 Media Guide

UUWMWM Men:Men: BBrokeroke 1010 RecordsRecords iinn 22007-08007-08 / HHorizonorizon LeagueLeague ChampionsChampions • 20002000 1 General Information Table of Contents School ..................................University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Quick Facts & Table of Contents ............................................1 City/Zip ......................................................Milwaukee, Wis. 53211 Panther Coaching Staff ........................................................2-5 Founded ...................................................................................... 1885 Head Coach Erica Janssen ........................................................2-3 Enrollment ............................................................................... 28,042 Assistant Coach Kyle Clements ..................................................4 Nickname ............................................................................. Panthers Diving Coach Todd Hill ................................................................4 Colors ....................................................................... Black and Gold Support Staff ...................................................................................5 Pool .................................................................Klotsche Natatorium 2008-09 UWM Schedule ..........................................................5 Capacity..........................................................................................400 Th e 2008-09 Season ..............................................................6-9 -

ID Lecture 7 Fossils 2014

Intelligent Design vs. Evolution Defending God’s Creation Genesis 1:1, 21, 25 1 In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth ! 21 So God created great sea creatures and every living thing that moves, with which the waters abounded, according to their kind, and every winged bird according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. ! 25 And God made the beast of the earth according to its kind, cattle according to its kind, and everything that creeps on the earth according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. Intelligent Design Critics “The argument for intelligent design basically depends on saying, ‘You haven’t answered every question with evolution.’ Well, guess what? Science can’t answer every question.” ! Kenneth Miller Brown University biologist Houston Chronicle, 10-22-05 Fossilization • Animal or plant must be buried quickly – Catastrophic event – Before decay or consumed • Buried with right mixture of minerals – Everything is replaced slowly with minerals and becomes hard as rock ! • Study of fossils is paleontology Nested Hierarchy • Biology classification developed by Carolus Linnaeus (pre-Darwin) • Organisms grouped by similarities and differences Humans Kingdom Animals Phylum Chordates Class Mammals Order Primates Family Hominids Genus Homo Species sapiens Fossil Record • Cambrian Explosion – “Biology’s Big Bang” • Transitional Fossils – Archaeopteryx • Reptile to mammal evolution • Whale evolution • Fish to Amphibian evolution Characteristics of Fossil Record ! • Sudden Appearance (Saltation) ! • Stasis ! • -

About the Wisconsin Policy Forum

About the Wisconsin Policy Forum The Wisconsin Policy Forum was created on January 1, 2018, by the merger of the Milwaukee-based Public Policy Forum and the Madison-based Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance. Throughout their lengthy histories, both organizations engaged in nonpartisan, independent research and civic education on fiscal and policy issues affecting state and local governments and school districts in Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Policy Forum is committed to those same activities and to that spirit of nonpartisanship. Preface and Acknowledgments This report was undertaken to paint a clearer picture of the youth sports landscape in the city of Milwaukee: what options are available to kids and their families, what are the characteristics of these programs and how are they supported financially, and what are some of the primary challenges facing the city’s youth sports organizations. We hope that this research will help guide youth sports leaders, funders, and policymakers. Report authors would like to thank the representatives of youth sports organizations who shared information by responding to our survey, as well as key informants who provided additional insight. In addition, we are grateful to members of the advisory committee convened to guide this report for generously providing their time and expertise; and to representatives from Milwaukee Recreation for taking the time to provide us with important information about the unique role they play in Milwaukee’s youth sports landscape. Finally, we wish to thank the Milwaukee Youth Sports Alliance for spearheading this initiative, and the Milwaukee Bucks and Bader Philanthropies for their contributions that helped make this research possible. -

Your Inner Fish : a Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body / by Neil Shubin.—1St Ed

EPILOGUE As a parent of two young children, I find myself spending a lot of time lately in zoos, museums, and aquaria. Being a visitor is a strange experience, because I’ve been involved with these places for decades, working in museum collections and even helping to prepare exhibits on occasion. During family trips, I’ve come to realize how much my vocation can make me numb to the beauty and sublime complexity of our world and our bodies. I teach and write about millions of years of history and about bizarre ancient worlds, and usually my interest is detached and analytic. Now I’m experiencing science with my children—in the kinds of places where I discovered my love for it in the first place. One special moment happened recently with my son at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. We’ve gone there regularly over the past three years because of his love of trains and the fact that there is a huge model railroad smack in the center of the place. I’ve spent countless hours at that one exhibit tracing model locomotives on their little trek from Chicago to Seattle. After a number of weekly visits 263 to this shrine for the train-obsessed, Nathaniel and I walked to corners of the museum we had failed to visit during our train-watching ventures or occasional forays to the full-size tractors and planes. In the back of the museum, in the Henry Crown Space Center, model planets hang from the ceiling and space suits lie in cases together with other memorabilia of the space program of the 1960s and 1970s. -

Govind Swarup: Radio Astronomer, Innovator Par Excellence and a Wonderfully Inspiring Leader

LIVING LEGENDS IN INDIAN SCIENCE Govind Swarup: Radio astronomer, innovator par excellence and a wonderfully inspiring leader G. Srinivasan They are ill discoverers that think there the important contributions to cosmology is no land, when they can see nothing but being made using this telescope. He sea. mentioned in very flattering terms the Francis Bacon Ph D thesis of one of Swarup’s students (Vijay Kapahi) which had come to him I must say at the outset that I have no for evaluation. That is how I came to special credentials to write an article know of Swarup. about as famous a person as Govind As it turned out, I moved from Cam- Swarup. I am not one of his numerous bridge to the Raman Research Institute students. Nor have I collaborated with (RRI), Bangalore in the beginning of him in research. Indeed, I am not even an 1976. Within weeks after my coming, I astronomer, let alone a radio astronomer. received an invitation from Govind Swa- But I have been one of his great admir- rup to attend a small meeting he had ers, and he has been a beacon of inspira- convened at RRI to discuss a Summer tion for me during the past four decades. School in Astronomy he was organizing I was therefore delighted – although sur- in Bangalore in June 1976. I was rather prised – when the Editor of Current Sci- surprised because I was still working in ence invited me to write this article. The Condensed Matter Physics. There were K. S. Krishnan, B. N. -

CV BOOKLET BIOGRAPHIES Raghda Abu-Shahla

CV BOOKLET BIOGRAPHIES RAGHDA ABU-SHAHLA Date of Birth: 31st August E-mail: [email protected] Biography Raghda Abu-Shahla is a committed activist for a better future towards peace, security and democracy in Palestine. Her work in Gaza with national and international organizations has enriched her understanding of issues of peace and development. She worked on EU and UK health development projects geared towards strengthening the health management field for the Palestinian Ministry of Health. Additionally, she worked with United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) on training for commercial crossings with Israel, and worked with the International Security Team of United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). The diversity of her work experiences over the past decade speak to her dedication of gaining a broader understanding of how to bring about change for peace. Raghda is a Leader for Democracy Fellow of Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs in New York, USA, a scholar of the Woodrow Wilson Center of International Scholars, and an International Peace and Security Leader (IPSI 2014). She has recently published an article, titled MENA Women: Opportunities and Obstacles in 2014 and a book titled Revolution By Love: Emerging Arab Youth Voices. She holds a Bachelor in English Literature and Master Degree in American Regional Studies. Personal Introduction I have spent most of my life in war-torn countries, and having had a first-hand experience of the ugliness of war, I became a committed believer in Peace of Palestine, promoting Peace & Gender Equality to create a better future for the generations to come. -

Causality and Patterns in Evolutionary Systems 1

Telmo Pievani Department of Biology [email protected] Bocconi University Master in Economic and Social Sciences GUEST LECTURE November 28, 2016 Taking History Seriously: causality and patterns in evolutionary systems 1. Experimental sciences VS historical sciences? HISTORICAL SCIENCES: No re-testing No counter-factuals “Hypotheses about the remote No clear repetitions past can never be tested by Different epistemic situations, etc. experiment, and so they are unscientific. No science can ever be historical” (Henry Gee, 1999, p. 5) (cladistics – nomothetic palaeontology) A «secundary status» with respect to EXPERIMENTAL SCIENCES? (Earth sciences, palaeontology, evol. biology, astrophysics?) The division between nomothetic and historical sciences does not mean that each science is exclusively one or the other. The particle physicist might find that the collisions of interest often occur on the surface of the sun; if so, a detailed study of that particular object might help to infer the general law. Symmetrically, the astronomer interested in obtaining an accurate description of the star might use various laws to help make the inference. … The same division exists within evolutionary biology. … Although inferring laws and reconstructing history are distinct scientific goals, they often are fruitfully pursued together. Theoreticians hope their models are not vacuous; they want them to apply to the real world of living organisms. Likewise, naturalists who describe the present and past of particular species often do so with an eye to providing data that have a wider theoretical significance. Nomothetic and historical disciplines in evolutionary biology have much to learn from each other . Elliott Sober (2000) Philosophy of Biology , pp. 14-15 It is quite impossible to find the exclusive cause of a particular phenomenon in biology. -

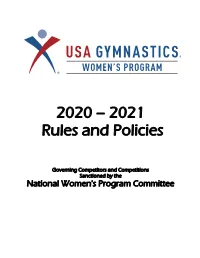

2020 – 2021 Rules and Policies

2020 – 2021 Rules and Policies Governing Competitors and Competitions Sanctioned by the National Women's Program Committee 2020 - 2021 Women's Program Rules and Policies Governing Competitors and Competitions sanctioned by the National Women's Program Committee Updated November 2020 Table of Contents National Women’s Program Committee Structure ………………………………………………………………………………………..... 1 Staff and Officers Directory ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Women’s Program Hotline ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 9 Women’s Program Regional Map …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 Purpose, Code of Ethical Conduct, Safe Sport ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 Chapter 1: Membership ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 18 • Athlete Membership ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 18 • Professional Membership and Responsibilities ……………………………………………………………………………….. 20 • Judges’ Responsibilities …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Chapter 2: Foreign Participants ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 24 Chapter 3: Sanctions ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 28 Chapter 4: Meet Director Responsibilities ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 31 Chapter 5: Meet Officials ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 34 • Criteria for Selection ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 37 • Rating Chart ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 39 • Duties of Meet Officials …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

GAME BOOK Games Bring Laughter, Excitement, Energy and Trust Into a Team

GAME BOOK Games bring laughter, excitement, energy and trust into a team. Here are more than 400 games designed to do just that at YOKE Club. GAME Just some help with leading games. 1. Make it exciting for the kids. DON’T be fake with your enthusiasm, but create an atmosphere of fun and excitement. 2. PARTICIPATE in the activities. The kids want you to interact with them. If you are not leading a game, you should be participating in it. 3. Give directions without sounding like you are. Use positive statements instead of negative ones. (“Don’t put your hand in the candle wax!” “Only the wicks go into the hot candle wax.”) 4. Use other YOKE Folk to act out right and wrong ways of completing a task. Have the kids repeat the rules in shorthand versions or with one word for each rule. 5. Start with excitement! Have the most energetic, fun games at the beginning then decrease the energy level to lead to a more serious atmosphere for the Talk. 6. Change things up. The games in Club in a Box are mixed up and not repeated. Don’t play the same games week after week. 7. Always have a backup plan or extra games. Sometimes it rains on parades; have other games to add if time passes slowly or if the weather proves to be troublesome. 2 GAME No Supplies Needed: Alphabet Game Little Sally Walker Tag: Dancing Freeze Tag Anatomy Monster Walk Tag: Duck Duck Goose Back-to-Back Mother, May I? Tag: Elbow Bedlam Murder Wink Tag: Everybody’s It Birdie on the Wire Name that Tune Tag: Follow Birthday Shuffle Pangaea Tag: Fox/Hound Box the Leader Poor Kitty Tag: -

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English Excerpted from Word Power, Public Speaking Confidence, and Dictionary-Based Learning, Copyright © 2007 by Robert Oliphant, columnist, Education News Author of The Latin-Old English Glossary in British Museum MS 3376 (Mouton, 1966) and A Piano for Mrs. Cimino (Prentice Hall, 1980) INTRODUCTION Strictly speaking, this is simply a list of technical terms: 30,680 of them presented in an alphabetical sequence of 52 professional subject fields ranging from Aeronautics to Zoology. Practically considered, though, every item on the list can be quickly accessed in the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (RHU), updated second edition of 2007, or in its CD – ROM WordGenius® version. So what’s here is actually an in-depth learning tool for mastering the basic vocabularies of what today can fairly be called American-Pronunciation Internationalist High Tech Latinate English. Dictionary authority. This list, by virtue of its dictionary link, has far more authority than a conventional professional-subject glossary, even the one offered online by the University of Maryland Medical Center. American dictionaries, after all, have always assigned their technical terms to professional experts in specific fields, identified those experts in print, and in effect held them responsible for the accuracy and comprehensiveness of each entry. Even more important, the entries themselves offer learners a complete sketch of each target word (headword). Memorization. For professionals, memorization is a basic career requirement. Any physician will tell you how much of it is called for in medical school and how hard it is, thanks to thousands of strange, exotic shapes like <myocardium> that have to be taken apart in the mind and reassembled like pieces of an unpronounceable jigsaw puzzle.