Queens´Love Always and Forever- Amor De Reina” – Latinas Who Chose to Join the Almighty Latin King and Queen Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewed Books

REVIEWED BOOKS - Inmate Property 6/27/2019 Disclaimer: Publications may be reviewed in accordance with DOC Administrative Code 309.04 Inmate Mail and DOC 309.05 Publications. The list may not include all books due to the volume of publications received. To quickly find a title press the "F" key along with the CTRL and type in a key phrase from the title, click FIND NEXT. TITLE AUTHOR APPROVEDENY REVIEWED EXPLANATION DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.2 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.3 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. Workbook of Magic Donald Tyson X 1/11/2018 SR per Mike Saunders 100 Deadly Skills Survivor Edition Clint Emerson X 5/29/2018 DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey X 4/6/2017 WCI DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b. b Teaches fighting techniques along with general fitness DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Is inconsistent with or poses a threat to the safety, 100 Things You’re Not Supposed to Know Russ Kick X 11/10/2017 WCI treatment or rehabilitative goals of an inmate. 100 Ways to Win a Ten Spot Paul Zenon X 10/21/2016 WRC DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 Years of Lynchings Ralph Ginzburg X reviewed by agency trainers, deemed historical Brad Graham and 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genuis Kathy McGowan X 12/23/10 WSPF 309.05(2)(B)2 309.04(4)c.8.d. -

Mob Speak ...Is the Way Mob Guys Talk

Dela Rapportera otillåten användning Nästa blogg» Skapa en blogg Logga in mob speak ...is the way mob guys talk. On this site you'll find a wide variety of mob-related stuff updated regularly. You can get up-to-date news on THIEF! book signings, radio and TV interviews, media info, and other THIEF! events by co-authors, Cherie Rohn & William 'Slick' Hanner. Mobwriter wants to hear from YOU. THIEF! The Gutsy, True Story of an Ex-Con Artist Followers Stay tuned for THIEF! book signings, media interviews and other THIEF! events Media Reviews posted periodically Mobwriter comments on true crime events and books THIEF! Website: Excerpts, author bios, reviews, mob THIEF! character, Vince Eli quiz, order link F R I D A Y , J U L Y ht6tp://ww,w.thief truesto2ry.com0 1 2 Part III: Supreme, Crack, Hip-hop & 50-Cent Free Forex Signals 1000+ of the best Day Part III of a 3-Part Series Traders. Watch and Follow. We take up again with Seth Sign up for free! www.ayondo.com/Forex Ferranti, author of The Supreme Team: The Birth of Crack and Hip- hop, Prince's Reign of Terror and Dålig Andedräkt? the Supreme/50-Cent Beef Frisk andedräkt på 3 minuter! Exposed. Prova Gratis Zinkoral från EFI www.EFI.se/Zinkoral Jay-Z & Supreme MS: Do you think Supreme and his gang believed they could outsmart the system or just accepted that death or prison was the price one paid? SF: I would say a lot of dudes know that death and prison are the eventual outcomes when they get involved in the drug game but to them it seems that is the acceptable eventuality. -

Praying Against Worldwide Criminal Organizations.Pdf

o Marielitos · Detroit Peru ------------------------------------------------- · Filipino crime gangs Afghanistan -------------------------------------- o Rathkeale Rovers o VIS Worldwide § The Corporation o Black Mafia Family · Peruvian drug cartels (Abu SayyafandNew People's Army) · Golden Crescent o Kinahan gang o SIC · Mexican Mafia o Young Boys, Inc. o Zevallos organisation § Salonga Group o Afridi Network o The Heaphys, Cork o Karamanski gang § Surenos or SUR 13 o Chambers Brothers Venezuela ---------------------------------------- § Kuratong Baleleng o Afghan drug cartels(Taliban) Spain ------------------------------------------------- o TIM Criminal o Puerto Rican mafia · Philadelphia · TheCuntrera-Caruana Mafia clan § Changco gang § Noorzai Organization · Spain(ETA) o Naglite § Agosto organization o Black Mafia · Pasquale, Paolo and Gaspare § Putik gang § Khan organization o Galician mafia o Rashkov clan § La ONU o Junior Black Mafia Cuntrera · Cambodian crime gangs § Karzai organization(alleged) o Romaniclans · Serbian mafia Organizations Teng Bunmaorganization § Martinez Familia Sangeros · Oakland, California · Norte del Valle Cartel o § Bagcho organization § El Clan De La Paca o Arkan clan § Solano organization Central Asia ------------------------------------- o 69 Mob · TheCartel of the Suns · Malaysian crime gangs o Los Miami o Zemun Clan § Negri organization Honduras ----------------------------------------- o Mamak Gang · Uzbek mafia(Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan) Poland ----------------------------------------------- -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42527-8 — Crack David Farber Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42527-8 — Crack David Farber Index More Information Index “Allah the Father,” 51–52 Black Mafia Family, 166–167 50 Cent, 56, 118 Blackstone Rangers, 67, 72, See Almighty 8-Tray Stones, 69–71 Black P. Stone Nation Abdul Malik Ka’bah. See Fort, Jeff Bloods, 45, 63, 76, 120 Adler, William, 105 Boesky, Ivan, 121, 181 Alexander, Michelle, 168–169, 171 Bolivia, 30, 33 Almighty Black P. Stone Nation, 52, 64, 66, Bourgois, Philippe, 6, 46, 84, 90, 124–125 69, 71, 72, 98 Bradbie, Juanita, 30 American Association for the Advancement Broadus Jr., Calvin. See Snoop Dogg of Science, 16 Buchalter, Louis “Lepke,” 106 American Temperance Society, 20 Bunting, Charles A., 15, 16 amphetamines, 27, 31 Burke, Kareem “Biggs,” 117 Amsterdam News, 134 Bush, George H.W., 6, 36, 146–151, 158, Anderson, Elijah, 88, 91, 94, 97, 107 170, 173–174 Anslinger, Harry, 28 Byrne, Edward, 58 Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, 7, 139, 142–143, 144, 171, 173, 177 Canada, 64 Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, 145 Candis, Adolph, 23 Antney, James “Bimmy”,54–55 carceral state Arbuckle, Fatty, 20 growth of, 7–8, 159, 171, 172 A-Team, 52 incarcerations, 151–154 opinions of, 168, 169, 171 Bad Boy Records, 113 sentencing, 139–144, 146, 162 Baker, James, 147 Carter, Shawn Corey. See Jay-Z Barksdale, “King” David, 72 Cayon, Manuel Garcia, 24 Barnes, Nicky, 98 Central Intelligence Agency, 41, 77, Bebos, 50, 58 177–179 Bennett, Brian “Waterhead Bo,” 77, 108 Chambers, Billy Joe, 105 Bennett, William, 149–151, 170 Chambers, Larry, 93, 101 Bey, Clifford, 98–100 Chicago Defender, 61, 155 Bias, Len, 112, 138 Chicago Police Department, 64, 65 Biden, Joe, 146–147, 150 Chicago Tribune, 71, 75, 158, 159 Biggie Smalls. -

United States District Court Middle District of Tennessee Nashville Division

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE NASHVILLE DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) No. 3:17-cr-00130 ) [1] JAMES WESLEY FRAZIER, ) [2] AELIX SANTIAGO, ) [3] KYLE HEADE, ) [6] JOEL ALDRIDGE, ) [7] JAMES HINES, ) [8] MICHAEL FORRESTER, JR., ) [10] JAMIE HERN, ) [12] MICHAEL MYERS, ) [13] MICHAEL LEVI WEST, ) [14] ADRIANNA FRAZIER, ) [15] DEREK LEIGHTON STANLEY, ) [16] WILLIAM NELPER, ) [17] WILLIAM BOYLSTON, ) [18] JASON MEYERHOLZ, ) [20] JESSIE MARIE DECKER, ) [21] JAMIE LEE ) ) Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND OMNIBUS ORDER On June 29, 2018, a federal grand jury returned a 75-count Third Superseding Indictment against twenty-one Defendants, who are alleged to be members or associates of the Clarksville, Tennessee Chapter of the Mongols Motorcycle Gang. The charges followed a three-year investigation, during which the Government compiled more than 20,000 pages of documents, including more than 350 reports of investigation by federal agents alone. In addition to the overarching charge contained in Count 1 alleging Conspiracy to Commit Racketeering Activity in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1962(d), the charges include: Conspiracy to Distribute and Possession with Intent to Distribute Fifty Grams or More of Methamphetamine, in Case 3:17-cr-00130 Document 998 Filed 09/06/19 Page 1 of 46 PageID #: <pageID> violation of 21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a)(1) and 846; Conspiracy to Commit Money Laundering, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1956(h); Violent Crimes in Aid of Racketeering, including Murder and Kidnapping in Aid of Racketeering, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1959(a)(1); Assault with a Dangerous Weapon in Aid of Racketeering, in violation of 18 U.S.C. -

A Retrospective (1990-2014)

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York: A Retrospective (1990-2014) The New York County Lawyers Association Committee on the Federal Courts May 2015 Copyright May 2015 New York County Lawyers Association 14 Vesey Street, New York, NY 10007 phone: (212) 267-6646; fax: (212) 406-9252 Additional copies may be obtained on-line at the NYCLA website: www.nycla.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COURT (1865-1990)............................................................ 3 Founding: 1865 ........................................................................................................... 3 The Early Era: 1866-1965 ........................................................................................... 3 The Modern Era: 1965-1990 ....................................................................................... 5 1990-2014: A NEW ERA ...................................................................................................... 6 An Increasing Docket .................................................................................................. 6 Two New Courthouses for a New Era ........................................................................ 7 The Vital Role of the Eastern District’s Senior Judges............................................. 10 The Eastern District’s Magistrate Judges: An Indispensable Resource ................... 11 The Bankruptcy -

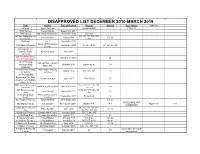

Disapproved List December 2010-March 2019

DISAPPROVED LIST DECEMBER 2010-MARCH 2019 Title Author Date of Review Page # Criteria Description Publisher 100 proof Henry Lee Law November 2018 C1,C2, C4 1000 Tattoos Carlton Books September 2017 I 1000 tattoos ED. Henk Schiffmacher December 2018 269, 358 I 101 Spy Gadgets for the 143-151, 193-215, 237- Second Edition August 2018 C5, C6 Evil Genius 249 12 Beast Vol. 3 November 2018 I foreword by Georges 120 Days of Sodom November 2015 31, 35, 46, 53 A1, A2, A3, A5 Bataille 199 Vaginas: The Ultimate Photo Keyser B. Soze June 2018 I Collection 2000 (Russian Book, January 18. 2017 G Need Translation) 2010 Nursing Patricia Dwyer Schull, spectrum drug October 2017 Entire book C4 MSN, RN handbook 2016 Standard Catalog 26th Edition edited by August 2018 328, 497, 907 C3 of Firearms Jerry Lee 23/7 Pelican Bay Prison and The Rise Keramet Reiter June 2017 17,41,55,59 D of Long Term Solitary Confinement 3000 solved problems in 212, 213, 214, 215, 220, David E. Goldberg Ph.D November 2018 C4 chemistry 221, 222 365 Essetial survial 17,22,28,73,80,123,167, Creek Stewart November 2018 C3 skills 258 4 Foreign Language Photo of book covers September 2018 Entire Book G Books recorded 52 Prepper Projects by David Nash 2015 September C3, C4 PAGES ARE NOT 5O Nights in Gray Laura Elias Novemeber 2014. NIGHT #15 A-1 Night # 15 A-1 NUMBERED A Dopegirl Needs Love 24, 112, 113, 120, 147, Part 2 by Shan June 2018 A1, A2 Too 148, 158, 168, 210 A Game of Thrones Graphic Novel Vol 3 October 2015 50, 51, 84, 145 I A Girl From Flint Treasure Hernandez August 2018 175-181 A1 A Hustler's Dream Ernest Morris January 2018 119 &148 A1 &2 A Hustler's Dream 2 Ernest Morris January 2018 54,55-57 &141 A1 &2 A Maid for All Seasons I & II Devlin O'Neil June 2018 132-141 A1-A4 A Nation of Lords by David Dawley February 2016 126, 172, 195, 199 I A Night In A Moorish Description of sexual H. -

Authorized Federal Capital Prosecutions Resulting in a Life Sentence - 6/10/2016

Authorized Federal Capital Prosecutions Resulting in a Life Sentence - 6/10/2016 Cooper, Alex N.D. IL No. 89-CR-580 Life sentence from jury Name of AG Thornburg Race & gender of def B M Victim R BM Date of DP notice 5/10/1990 two black Chicago gang members received life sentences for the cocaine-related murder of an informant after separate trials. The Government had offered one defendant, but not the other, a plea bargain prior to trial. 19 F.3d 1154 (7th Cir. 1994). Davis, Darnell Anthony N.D. IL No. 89-CR-580 Life sentence from jury Name of AG Thornburg Race & gender of def B M Victim R BM Date of DP notice 5/10/1990 two black Chicago gang members received life sentences for the cocaine-related murder of an informant after separate trials. The Government had offered one defendant, but not the other, a plea bargain prior to trial. 19 F.3d 1154 (7th Cir. 1994). Pitera, Thomas E.D. NY CR No. 90-0424 (RR) Life sentence from jury Name of AG Barr Race & gender of def W M Victim R WF WM HM Date of DP notice 2/8/1991 a white Mafia contract killer, the first person with mob connections to face the federal death penalty, received a life sentence from a Brooklyn, New York jury after being convicted of seven murders, two of which qualified as capital crimes under 21 U.S.C. § 848(e). Several of the murders involved torture and dismemberment of the victims. 5 F.3d 624 (2d Cir. -

Hamper Local Radio

EDISON 1 FORDS BEACON Woodbridgc, Avenel, Colonia, Fords, Hopelfrwn, Isclin, Keasbey, Port Reading, Senrarcn and Edison PiiWIiflrcl Wffltly Woodbridge, N. J., Thursday, January 31, KnterM at 2nd cinw Mall Twenty Pages No. 49 <>n t'hursdny At P. O., Woodbrldg'e. N. J. Price Ten Cents S'1 * t Survey ol Township Census Work liy Block Is !\C«MI<*(1 lo Draw ,Recreation Department Ward Lines, He Says WOODBRIDGE-- DlscuffiW Oir m w ward allKiimcnts which Income effective with publica- tion elsewhere in this Issue of .Tlii' Independent - Leader, Miivnr Walter Zlrpolo said to- Outlines Inadequacies day (hut he "hopes to Ret the Kid'inl Bureau of Census to — come into the Township and I ;ike a tomplfte cmsus of Wi odbridse, blo<-k by block, so Fallon that there will be an adpquate bn.*w for dranlns Ward and v\oltlllV CHARITY: The WniHllirldgc Moris Club cave Ms annual nV District lines." i,, n,,' Mt. Ciii-mrl Nuriint Ciulld ihK week, l.i-ft t<i rinhi: Bernard F. i The mayor explained that Releases i I till I irsl Vlrr I'rrtadrnt; Rt. Krv. Monsimmr Charles (.. MeCorristin, the ecu'-us tracts used by the ,, l.uiUI .mil pastor of *t. lamn Chiirrh. Wnndhrldtr; Kr;,uris Mulligan. Federal bureau every ten years i.imn' Miuiirc committee and Earl Koenix, president, are "without any real form as far as Ward alignments are; Report concerned." Candidates Speak: However, he stated the Coun- WOODBRIDGE — "Even ty Election Board and the Uiou'th the total acreage of Township Clerk, who made up parks and playgrounds falls far the Ward Commissioners as short of jhc current recreation outlined by the new charter, standards, all are developed and \il. -

Authorized Federal Capital Prosecutions Arising in Non-Death Penalty States - 6/10/2016

Authorized Federal Capital Prosecutions Arising in Non-Death Penalty States - 6/10/2016 Brown, Reginald E.D. MI CR No. 92-81127 Innocent Name of AG Barr Race & gender of def B M Victim R BF BM Date of DP notice 8/11/1993 involves eight drug-related gun murders by an innocent gang member. After insisting for nearly two years he had murdered four people, including a child, the government dismissed capital murder charges against a Detroit man and began prosecuting a co-defendant for the same killings. All involved are African-American. Brown, Terrance E.D. MI CR No. 92-81127 Killed or died after authorization Name of AG Barr Race & gender of def B M Victim R BM Date of DP notice 8/11/1993 involves eight gun murders by a drug gang member who himself was found shot to death after the Attorney General approved a capital prosecution. Culbert, Stacy E.D. MI CR No. 92-81127 Guilty plea at trial Name of AG Barr Race & gender of def B M Victim R BM Date of DP notice 7/22/1994 involves eight gun murders by a drug gang member. A prosecutor claimed that the gang was involved in up to 50 murders. Goldston, Anthony D. DC CR No. 92-CR-284-01 Authorization withdrawn Name of AG Reno Race & gender of def B M Victim R BM Date of DP notice involves eight killings. Four African-American D.C. residents who were charged with a total of eight murders as leaders of a District of Columbia drug gang known as the Newton Street Crew. -

EARH WORLD FRANKS BANANAS Lb

\ ■ I iM' .I t s si > V* i i t I..-,-— \ ;/ ■-.f, • I ■ t J h .r': f \ -It ■ ' • ■ -v ^ESDAY, JANUARY 14, 1968 PAGE FOURTEEN Average Dailjr IHot I^em Ran The Weather For the W e^ Ended Forecast of U; 8. weather Barsan Jaau aiy I L 1008 The monthly meeting of St. Blest, rain iwdlng, elsndy, esst- Margaret's Circle, Junior Daugh Engaged 126 Pints of •Blood Collected Engaged BaU Patrons NEV\/> 12,612 ar tenlghL Lsw 98-M. Thnrsilny About Town ters of Isabella, scheduled for tOr ooenslonnl rain sr sasw ikiinkiplng fg M / T H IWWtlM' *2 ti** Audit night, has been postponed. Mem \, ■ lata la day. High $$-$5. Th« Greater Hartford Hoitie Bnnaa at Clrcnlatlon ber^ will be contacted'shout the At Monthly Bloodrriohile VMt Should Reply M anchetter-^A City o f ViUage Charm BSconomica Club will have a eoclal next| meeting. M U 1 I I I I - A N ■ . I ■ ■ card party at its next meeting on h e a r i n g AIPj Jan. 21 at 7:30 p.ni. at the Talcott The Homemakers Holiday meet Despite a record number of James Coughlin,; Austin Cham- 'By Thursday Junior High School, West Hart ing which was canceled last persons who, failed to appear for bera, Everett Cramer. *6 5 «o VOL. LXXVIL NO. 89. (TWENTY-FOtJR PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 15, 1958 tCtaaoUMI AdvarUang sn Psgs. tS) PRICE FIVE CENTS ford. All members, professional Wednesday will be held torrjorrow their appointments, yesterday's Also, Michael Clvlello, Tom Car Residents Invited to be patrons bomb economics and interested All iIm power tnd pcriormtnc* ettoim morning at 9:30 at the Comrntmlty penter, G. -

Marria V. Broadus

Marria v. Broaddus, Not Reported in F.Supp.2d (2003) [2] Constitutional Law KeyCite Yellow Flag - Negative Treatment Beliefs Protected; Inquiry Into Beliefs Declined to Follow by Harrison v. Watts, E.D.Va., March 26, 2009 2003 WL 21782633 Analysis of whether a claimant sincerely holds a Only the Westlaw citation is currently available. particular belief and whether the belief is United States District Court, religious in nature, and thus subject to protection S.D. New York. under free exercise clause of First Amendment, seeks to determine the subjective good faith of Rashaad MARRIA, Plaintiff, an adherent in performing certain rituals and can v. be guided by such extrinsic factors as a Dr. Raymond BROADDUS, Deputy Commissioner purported religious group’s size and history, of Programs; G. Blaetz, Chairperson of Green whether the claimant appears to be seeking Haven Correctional Facility Media Review material gain by hiding secular interests behind Committee; Warith Deen Umar, Coordinator for a veil of religious doctrine, and whether the Islamic Affairs; and Glenn Goord, Commissioner claimant has acted in a manner inconsistent with of the New York State Department of Corrections, his professed beliefs; however, courts are not Defendants. permitted to ask whether a particular belief is appropriate or true, however unusual or No. 97 Civ.8297 NRB. | July 31, 2003. unfamiliar the belief may be. U.S.C.A. Const.Amend. 1. Prisoner brought action against New York State Department of Correctional Services (DOCS) and various 2 Cases that cite this headnote officials alleging violation of his rights under First Amendment and Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA).