The Framers' Intent: John Adams, His Era, and the Fourth Amendment†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Sculpture Census / Répertoire De Sculpture Française

FRENCH SCULPTURE CENSUS / RÉPERTOIRE DE SCULPTURE FRANÇAISE BINON, Jean-Baptiste born in Lyon, Rhône John Adams (1735-1826), second président des Etats- Unis, de 1797 à 1801 John Adams (1735-1826), Second President of the United States, 1797-1801 1819 plaster bust 3 1 7 25 ?16 x 20 ?16 x 10 ?8 in. inscribed on base: J.B. BINON / BOSTON Acc. No.: UH176 Credit Line: Gift of the artist, 1819 (UH176) Photo credit: photograph by Jerry L. Thompson © Artist : Boston, Massachusetts, Boston Athenaeum www.bostonathenaeum.org Provenance 1819, Gift of the artist Bibliography Boston Athenaeum's website, August 20, 2015 2006 Dearinger David B. Dearinger, in Stanley Ellis Cushing and David B. Dearinger, eds., Acquired Tastes: 200 Years of Collecting for the Boston Athenæum (2006), p. 265-268 (see text below) Exhibitions 1839 Boston Annual exhibition, Boston, Boston Athenæum, 1839, no. 26 1980 Boston A Climate for Art: The History of the Boston Athenæum Gallery, 1827-1873, Boston, Boston Athenæum, October 3 - October 29, 1980, no. 118 2007 Boston Acquired Tastes: 200 Years of Collecting for the Boston Athenaeum, Boston, Boston Athenæum, February 12 - July 13, 2007, no. 81 Comment Boston Athenaeum website, August 20, 2015: David B. Dearinger, from Stanley Ellis Cushing and David B. Dearinger, eds., Acquired Tastes: 200 Years of Collecting for the Boston Athenæum (2006): 265-268. Copyright © The Boston Athenæum: In February 1818 the Massachusetts state legislature passed a resolution to commission a marble bust of former president John Adams for Faneuil Hall in Boston. Typical of members of such bodies, the legislators had second thoughts, however, and one week later voted to delay the project indefinitely. -

50 Properties Listed in Or Determined Eligible for the NRHP Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6

Properties Listed In or Determined Eligible for the NRHP Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 (NR-2410; IHSSI # 098-296-01173), 1801 Nowland Avenue The Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 was listed in the NRHP in 2016 under Criteria A and C in the areas of Architecture and Education for its significance as a Carnegie Library (Figure 4, Sheet 8; Table 20; Photo 43). Constructed in 1911–1912, the building consists of a two-story central block with one-story wings and displays elements of the Italian Renaissance Revival and Craftsman styles. The building retains a high level of integrity, and no change in its NRHP-listed status is recommended. Photo 43. Indianapolis Public Library Branch No. 6 (NR-2410; IHSSI # 098-296-01173), 1801 Nowland Avenue. Prosser House (NR-0090; IHSSI # 098-296-01219), 1454 E. 10th Street The Prosser House was listed in the NRHP in 1975 under Criterion C in the areas of Architecture and Art (Figure 4, Sheet 8; Table 20; Photo 44). The one-and-one-half-story cross- plan house was built in 1886. The original owner was a decorative plaster worker who installed 50 elaborate plaster decoration throughout the interior of the house. The house retains a high level of integrity, and no change to its NRHP-listed status is recommended. Photo 44. Prosser House (NR-0090; IHSSI # 098-296-01219), 1454 E. 10th Street. Wyndham (NR-0616.33; IHSSI # 098-296-01367), 1040 N. Delaware Street The Wyndham apartment building was listed in the NRHP in 1983 as part of the Apartments and Flats of Downtown Indianapolis Thematic Resources nomination under Criteria A and C in the areas of Architecture, Commerce, Engineering, and Community Planning and Development (Figure 4, Sheet 1; Table 20; Photo 45). -

Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment As Justice of the Peace

Catholic University Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Winter 1996 Article 2 1996 Marbury's Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment as Justice of the Peace. David F. Forte Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation David F. Forte, Marbury's Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment as Justice of the Peace., 45 Cath. U. L. Rev. 349 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol45/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES MARBURY'S TRAVAIL: FEDERALIST POLITICS AND WILLIAM MARBURY'S APPOINTMENT AS JUSTICE OF THE PEACE* David F. Forte** * The author certifies that, to the best of his ability and belief, each citation to unpublished manuscript sources accurately reflects the information or proposition asserted in the text. ** Professor of Law, Cleveland State University. A.B., Harvard University; M.A., Manchester University; Ph.D., University of Toronto; J.D., Columbia University. After four years of research in research libraries throughout the northeast and middle Atlantic states, it is difficult for me to thank the dozens of people who personally took an interest in this work and gave so much of their expertise to its completion. I apologize for the inevita- ble omissions that follow. My thanks to those who reviewed the text and gave me the benefits of their comments and advice: the late George Haskins, Forrest McDonald, Victor Rosenblum, William van Alstyne, Richard Aynes, Ronald Rotunda, James O'Fallon, Deborah Klein, Patricia Mc- Coy, and Steven Gottlieb. -

John-Adams-3-Contents.Pdf

Contents TREATY COMMISSIONER AND MINISTER TO THE NETHERLANDS AND TO GREAT BRITAIN, 1784–1788 To Joseph Reed, February 11, 1784 Washington’s Character ....................... 3 To Charles Spener, March 24, 1784 “Three grand Objects” ........................ 4 To the Marquis de Lafayette, March 28, 1784 Chivalric Orders ............................ 5 To Samuel Adams, May 4, 1784 “Justice may not be done me” ................... 6 To John Quincy Adams, June 1784 “The Art of writing Letters”................... 8 From the Diary: June 22–July 10, 1784 ............. 9 To Abigail Adams, July 26, 1784 “The happiest Man upon Earth”................ 10 To Abigail Adams 2nd, July 27, 1784 Keeping a Journal .......................... 12 To James Warren, August 27, 1784 Diplomatic Salaries ......................... 13 To Benjamin Waterhouse, April 23, 1785 John Quincy’s Education ..................... 15 To Elbridge Gerry, May 2, 1785 “Kinds of Vanity” .......................... 16 From the Diary: May 3, 1785 ..................... 23 To John Jay, June 2, 1785 Meeting George III ......................... 24 To Samuel Adams, August 15, 1785 “The contagion of luxury” .................... 28 xi 9781598534665_Adams_Writings_791165.indb 11 12/10/15 8:38 AM xii CONteNtS To John Jebb, August 21, 1785 Salaries for Public Officers .................... 29 To John Jebb, September 10, 1785 “The first Step of Corruption”.................. 33 To Thomas Jefferson, February 17, 1786 The Ambassador from Tripoli .................. 38 To William White, February 28, 1786 Religious Liberty ........................... 41 To Matthew Robinson-Morris, March 4–20, 1786 Liberty and Commerce....................... 42 To Granville Sharp, March 8, 1786 The Slave Trade............................ 45 To Matthew Robinson-Morris, March 23, 1786 American Debt ............................ 46 From the Diary: March 30, 1786 .................. 49 Notes on a Tour of England with Thomas Jefferson, April 1786 ............................... -

Boston Elites and Urban Political Insurgents During the Early Nineteenth Century

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1997 "The am gic of the many that sets the world on fire" : Boston elites and urban political insurgents during the early nineteenth century. Matthew H. rC ocker University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Crocker, Matthew H., ""The am gic of the many that sets the world on fire" : Boston elites and urban political insurgents during the early nineteenth century." (1997). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1248. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1248 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 312Dbb 2 b M D7fl7 "THE MAGIC OF THE MANY THAT SETS THE WORLD ON FIRE" BOSTON ELITES AND URBAN POLITICAL INSURGENTS DURING THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY A Dissertation Presented by MATTHEW H. CROCKER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 1997 Department of History © Copyright by Matthew H. Crocker 1997 All Rights Reserved • "THE MAGIC OF THE MANY THAT SETS THE WORLD ON FIRE" BOSTON ELITES AND URBAN POLITICAL INSURGENTS DURING THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY A Dissertation Presented by MATTHEW H. CROCKER Approved as to style and content by C It. Ja Jack fpager, Chair Bruce Laurie , Member Ronald Story, Member Leonard Richards , Member 6^ Bruce Laurie, Department Head History ABSTRACT "THE MAGIC OF THE MANY THAT SETS THE WORLD ON FIRE": BOSTON ELITES AND URBAN POLITICAL INSURGENTS DURING THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY SEPTEMBER 1997 MATTHEW H. -

The Framers, Faith, and Tyranny

Roger Williams University Law Review Volume 26 Issue 2 Vol. 26: No. 2 (Spring 2021) Article 7 Symposium: Is This a Christian Nation? Spring 2021 The Framers, Faith, and Tyranny Marci A. Hamilton University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Hamilton, Marci A. (2021) "The Framers, Faith, and Tyranny," Roger Williams University Law Review: Vol. 26 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR/vol26/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roger Williams University Law Review by an authorized editor of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Framers, Faith, and Tyranny Marci A. Hamilton* “Cousin America has run off with a Presbyterian parson, and that was the end of it.” —Horace Walpole1 INTRODUCTION There was a preponderance of Calvinists at the Constitutional Convention, nearly one fifth of whom were graduates of the preeminent Presbyterian college of the day, the College of New Jersey, which is now Princeton University.2 Over one third had direct connections to Calvinist beliefs. These leaders of the time reflected on their collective knowledge and experiences for usable theories to craft a governing structure in the face of the crumbling Articles of Confederation. They were in an emergency and felt no compunction to distinguish between governing ideas that were secular or theological in origin. Accounts of the Constitution’s framing rarely credit its Calvinist inspiration. -

The Winslows of Boston

Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV FAMILY MEMORIAL The Winslows of Boston Isaac Winslow Margaret Catherine Winslow IN FIVE VOLUMES VOLUME IV Boston, Massachusetts 1837?-1873? TRANSCRIBED AND EDITED BY ROBERT NEWSOM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 2009-10 Not to be reproduced without permission of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV Editorial material Copyright © 2010 Robert Walker Newsom ___________________________________ All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this work, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission from the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts. Not to be reproduced without permission of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV A NOTE ON MARGARET’S PORTION OF THE MANUSCRIPT AND ITS TRANSCRIPTION AS PREVIOUSLY NOTED (ABOVE, III, 72 n.) MARGARET began her own journal prior to her father’s death and her decision to continue his Memorial. So there is some overlap between their portions. And her first entries in her journal are sparse, interrupted by a period of four years’ invalidism, and somewhat uncertain in their purpose or direction. There is also in these opening pages a great deal of material already treated by her father. But after her father’s death, and presumably after she had not only completed the twenty-four blank leaves that were left in it at his death, she also wrote an additional twenty pages before moving over to the present bound volumes, which I shall refer to as volumes four and five.* She does not paginate her own pages. I have supplied page numbers on the manuscript itself and entered these in outlined text boxes at the tops of the transcribed pages. -

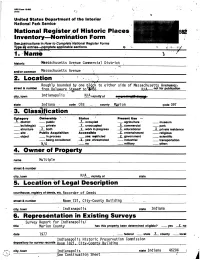

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form \M N A

NPS Form 10-900 (7-81) United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See4rjstructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type a\} entries—cqmptete applicable sections____________O \m N a rife historic Massachusetts Avenue Commercial District , 2. Location Roughly bounded by one block to either side of Massachusetts Avem«t3> street & number from Delaware Styeef tQ fca%5-_____-___________N/A—— not for publication city, town Indianapolis N/A vicinityof state Indiana code 018 county Marion code 097 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use — A district public X occupied agriculture - museum building(s) privpt<» X unoccupied X commercial park structure JLboth X work in progress X educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible X entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted X government scientific being considered X yes :y unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military other: 4. Owner off Property name Multiple street & number city, town N/A_ vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Recorder of Deeds street & number Room.721, City-County Building city, town ' Indianapolis state Indiana 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Survey Report for Indianapolis/ title Marion County _____ has this property been determined eligible? yes _ X_ no date 1977 federal __ state X county local Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission depository for survey records Room 182 1. Clty-CoQnty Building_______ city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 46204 See Continuation Sheet 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site _X _ good ruins X altered mnveri date N/A J(_falr unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Massachusetts Avenue extends northeast from Monument Circle, the center of the original Mile Square plat of Indianapolis, and the heart of downtown. -

C. 1820 Plaster;Marble;Plaster;Plaster;Painted Plaster, Hollow Bust;Bust;Bust;Bust;Bust

FRENCH SCULPTURE CENSUS / RÉPERTOIRE DE SCULPTURE FRANÇAISE cast made in 1819-1820 from 1818 marble;1818;1819;1818;c. 1820 plaster;marble;plaster;plaster;painted plaster, hollow bust;bust;bust;bust;bust 3 1 7 3 7 1 25 x 20 x 14 in.;25 ?16 x 20 ?16 x 10 ?8 in.;26 ?16 x 19 ?8 x 9 ?16 in.;24 x 17 x 10; 1 base: 5 x 9 ?2 x 8 in. inscribed on base: J.B. BINON / BOSTON;signed front of base: JB BINON;on left end of base: J.B.Binon / Boston Acc. No.: 2002-20;UH176;P50;1935.006 Credit Line: Gift of the artist, 1819 (UH176);Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of the Hon. John Davis to the University, 1819;Gift of the New Hampshire Society of Cincinnati Photo credit: © Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello ;ph. Wikimedia/Daderot;photograph by Jerry L. Thompson;ph. courtesy New Hampshire Historical Society © Artist : Provenance 1818-1820, cast made from marble bust at Faneuil Hall, Boston 1825, given to Jefferson by Benjamin Gould;bust acquired by 215 subscribers to be exhibited at Faneuil Hall, Boston;1819, Gift of the artist;c. 1902, Placed in Cincinnati Memorial Hall by Col. Daniel Gilman (1851-1923), the grandson of Nathaniel Gilman (1759-1847), a younger brother of John Taylor Gilman 1935, Given to the New Hampshire Historical Society by the New Hampshire Society of Cincinnati with the approval of Daniel Gilman's son, Daniel E. Gilman (1889-1978) Art historian William B. Miller, Colby College, suggested this bust was done posthumously in Portland, Maine, in 1850-1852. -

MIDNIGHT JUDGES KATHRYN Turnu I

[Vol.109 THE MIDNIGHT JUDGES KATHRYN TuRNu I "The Federalists have retired into the judiciary as a strong- hold . and from that battery all the works of republicanism are to be beaten down and erased." ' This bitter lament of Thomas Jefferson after he had succeeded to the Presidency referred to the final legacy bequeathed him by the Federalist party. Passed during the closing weeks of the Adams administration, the Judiciary Act of 1801 2 pro- vided the Chief Executive with an opportunity to fill new judicial offices carrying tenure for life before his authority ended on March 4, 1801. Because of the last-minute rush in accomplishing this purpose, those men then appointed have since been known by the familiar generic designation, "the midnight judges." This flight of Federalists into the sanctuary of an expanded federal judiciary was, of course, viewed by the Republicans as the last of many partisan outrages, and was to furnish the focus for Republican retaliation once the Jeffersonian Congress convened in the fall of 1801. That the Judiciary Act of 1801 was repealed and the new judges deprived of their new offices in the first of the party battles of the Jeffersonian period is well known. However, the circumstances surrounding the appointment of "the midnight judges" have never been recounted, and even the names of those appointed have vanished from studies of the period. It is the purpose of this Article to provide some further information about the final event of the Federalist decade. A cardinal feature of the Judiciary Act of 1801 was a reform long advocated-the reorganization of the circuit courts.' Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the judicial districts of the United States had been grouped into three circuits-Eastern, Middle, and Southern-in which circuit court was held by two justices of the Supreme Court (after 1793, by one justice) ' and the district judge of the district in which the court was sitting.5 The Act of 1801 grouped the districts t Assistant Professor of History, Wellesley College. -

The Summer of 1787: Getting a Constitution

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 27 Issue 3 Article 6 7-1-1987 The Summer of 1787: Getting a Constitution J. D. Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Williams, J. D. (1987) "The Summer of 1787: Getting a Constitution," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 27 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol27/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Williams: The Summer of 1787: Getting a Constitution the summer of 1787 getting a constitution J D williams it is not at all certain that complex historical events really have beginnings but it is absolutely certain that all essays must and so we begin with my favorite living frenchman jean francois revel commenting on the revolution in eighteenth century america that revolution was in any case the only revolution ever to keep more promises than it broke 51 what made that possible in america was the constitution of the united states written eleven years after the declara- tion of independence and six years after our defeat of the british at yorktown on 17 september 1987 that document was two hundred years old and it is to that birthday and to all of us that this essay is fondly dedicated my intent here is threefold to recall how one american government the -

Free Trade & Family Values: Kinship Networks and the Culture of Early

Free Trade & Family Values: Kinship Networks and the Culture of Early American Capitalism Rachel Tamar Van Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Rachel Tamar Van All Rights Reserved. ABSTRACT Free Trade & Family Values: Kinship Networks and the Culture of Early American Capitalism Rachel Tamar Van This study examines the international flow of ideas and goods in eighteenth and nineteenth century New England port towns through the experience of a Boston-based commercial network. It traces the evolution of the commercial network established by the intertwined Perkins, Forbes, and Sturgis families of Boston from its foundations in the Atlantic fur trade in the 1740s to the crises of succession in the early 1840s. The allied Perkins firms and families established one of the most successful American trading networks of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and as such it provides fertile ground for investigating mercantile strategies in early America. An analysis of the Perkins family’s commercial network yields three core insights. First, the Perkinses illuminate the ways in which American mercantile strategies shaped global capitalism. The strategies and practices of American merchants and mariners contributed to a growing international critique of mercantilist principles and chartered trading monopolies. While the Perkinses did not consider themselves “free traders,” British observers did. Their penchant for smuggling and seeking out niches of trade created by competing mercantilist trading companies meant that to critics of British mercantilist policies, American merchants had an unfair advantage that only the liberalization of trade policy could rectify.