The Empathetic Architect by Mary N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stupid Starchitect Debate

THE STUPID STARCHITECT DEBATE “Here’s to the demise of Starchitecture!” wrote Beverly Willis, in The New York Timesrecently. Willis, through her foundation, has done much to promote the value of architecture. But like many critics of celebrity architecture, she gets it wrong: “In my 55-plus years of practice and involvement in architecture, I have witnessed the birth and — what I hope will soon be — the demise of the star architect.” The last few years has seen the rise of the snarky, patronizing term “starchitect,” (a term I refuse to use outside this context, much to the annoyance of editors seeking click-bait). But big-name architects creating spectacular, expensive buildings that from time to time prove to be white elephants have always been with us. Think Greek temples, Hindu Palaces, Chinese gardens, and monumental Washington, DC. The Times clearly struck a nerve by running a starchitecture story of utter laziness by author and emeritus professor Witold Rybczynski. That story led to a “Room for Debate” forum offering a variety of solicited points of view, and another more recent forum in which the Times asked readers to respond to a thoughtful letter by Peggy Deamer, an architect (and friend) who teaches at Yale. WHINING ABOUT CELEBRITY ARCHITECTURE I have written a great deal about celebrity architects as well as practitioners of what Rybczynski calls “locatecture.” He names no architects that stick to their own city, however, which says to me he doesn’t really care about the kind of practitioner he claims to celebrate. He’d rather just complain about flashy architecture than deeply examine it. -

Starchitect:” Wright Finds His Voice After Being Fired

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 5, Issue 3– Pages 301-318 After the “Starchitect:” Wright Finds his Voice after Being Fired By Michael O'Brien * The term ―Starchitect‖ seems to have originated in the 1940’s to describe a ―film star who has designed a house‖ but of late has been understood as an architect who has risen to celebrity status in the general culture. Louis Sullivan, like Daniel Burnham, might have been considered a ―starchitect.‖ Starchitects are frequently associated with a unique style or approach to architecture and all who work for them, adopt this style as their own as a matter of employment. Frank Lloyd Wright was one of these architects, working under and in the idiom of Louis Sullivan for six years, learning to draw and develop motifs in the style of Louis Sullivan. Frank Lloyd Wright’s firing by Louis Sullivan in 1893 and his rapidly growing family set him on an urgent course to seek his own voice. The bootleg houses, designed outside the contract terms Wright had with Adler and Sullivan caused the separation, likely fueled by both Sullivan and Wright’s ego, which left Wright alone, separated from his ―Lieber Meister‖1 or ―Beloved Master.‖ These early houses by Wright were adaptations of various styles popular in the times, Neo-Colonial for Blossom, Victorian for Parker and Gale, each, as Wright explained were not ―radical‖ because ―I could not follow up on them.‖2 Wright, like many young architects, had not yet codified his ideas and strategies for activating space and form. How does one undertake the search for one’s language of these architectural essentials? Does one randomly pursue a course of trial and error casting about through images that capture one’s attention? Do we restrict our voice to that which has already been voiced in history? Wright’s agenda would have included the merging of space and enclosure with site and nature structured as he understood it from Sullivan’s Ornament. -

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower by KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower BY KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO We were just getting used to the idea of seeing a sensuous Zaha Hadid building on the corporate-modernist boulevard that is Manhattan’s Park Avenue, but looks like we’ll have to keep dreaming. An invited competition to design a new Park Avenue office building for L&L Holdings and Lemen Brothers Holdings pitted starchitect against starchitect (with a shortlist including Hadid and Rem Koolhaas’s firm OMA). In the end, Lord Norman Foster came out victorious. “Our aim is to create an exceptional building, both of its time and timeless, as well as being respectful of this context,” said Norman Foster in a statement, according to The Architects’ Newspaper. Foster described the building as “for the city and for the people that will work in it, setting a new standard for office design and providing an enduring landmark that befits its world-famous location.” The winning design (pictured left) is a three-tiered, 625,000-square-foot tower. With sky-high landscaped terraces, flexible floor plates, a sheltered street-level plaza, and LEED certification, the building does seem to reiterate some of the same principles seen in the Lever House and Seagram Building, Park Avenue’s current office tower icons, but with markedly updated standards. Only time will tell if Foster’s building can achieve the same timelessness as its mid-century predecessors, a feat that challenged a slew of architects as Park Avenue cultivated its corporate identity in the 1950s and 60s. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Starchitect NSF- 1010624

Starchitect NSF- 1010624 Summative Evaluation for Space Science Institute By Kate Haley Goldman Patricia A. Montano Emily Craig Erin Wilcox Audience Viewpoints Consulting January 2016 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES 3 LIST OF FIGURES 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT BACKGROUND 6 STARCHITECT GAME CONTEXT 8 METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLE 8 Game-wide Sample 9 SAMPLE: CONTROLLED STUDY 14 WHAT WAS THE NATURE OF GAME PLAY? 17 FINDINGS: CONTROLLED STUDY 25 SCIENCE CONFIDENCE 25 NO CHANGE IN ASTRONOMY INTEREST 28 SELF-PERCEPTION OF KNOWLEDGE 29 MEASURED KNOWLEDGE 30 LEARNED FROM THE GAME 34 MOTIVATION FOR PLAYING 35 REFLECTION ON LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE PROJECT 42 REFERENCES 49 APPENDIX A: PRE SURVEY 51 APPENDIX B: POST SURVEY 59 APPENDIX C: TELEPHONE INTERVIEW 68 Starchitect Summative Evaluation 2 Audience Viewpoints Consulting List of Tables Table 1: Where Players Found Out about Starchitect ..................................................................... 9 Table 2: Age Provided Game-Wide ............................................................................................................ 9 Table 3: Gender provided Game-wide ................................................................................................. 12 Table 4: Gender Game-wide....................................................................................................................... 12 Table 5: Starchitect Players are More Knowledgeable about Science than the General Public ........................................................................................................................................................... -

The Avant-Garde Architecture of Three 21St Century Universal Art Museums

ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS by Leslie Elaine Reid APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Richard Brettell, Chair ___________________________________________ Nils Roemer ___________________________________________ Maximilian Schich ___________________________________________ Charissa N. Terranova Copyright 2019 Leslie Elaine Reid All Rights Reserved ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS by LESLIE ELAINE REID, MLA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES - AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank, in particular, two people in Paris for their kindness and generosity in granting me interviews, providing electronic links to their work, and emailing me data on the Louvre-Lens for my dissertation. Adrién Gardère of studio adrien gardère and Catherine Mosbach of mosbach paysagists gave hours of their time and provided invaluable insight for this dissertation. And – even after I had returned to the United States, they continued to email documents that I would need. March 2019 iv ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS Leslie Elaine Reid, PhD The University of Texas at Dallas, 2019 ABSTRACT Supervising Professor: Richard Brettell Rooted in the late 18th and 19th century idea of the museum as a “library of past civilizations,” the universal or encyclopedic museum attempts to cover as much of the history of mankind through “art” as possible. -

The Values of Starchitecture: Commodification of Architectural Design in Contemporary Cities Davide Ponzini Politecnico Di Milano, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DigitalCommons@WPI Volume 3 | Issue 1 Pages 10 - 18 5-17-2014 The Values of Starchitecture: Commodification of Architectural Design in Contemporary Cities Davide Ponzini Politecnico di Milano, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/oa Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Business Commons To access supplemental content and other articles, click here. Recommended Citation Ponzini, Davide (2014) "The Values of Starchitecture: Commodification of Architectural Design in Contemporary Cities," Organizational Aesthetics: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, 10-18. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/oa/vol3/iss1/4 This Special Topic is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Organizational Aesthetics by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WPI. Organizational Aesthetics 3(1): 10-18 © The Author(s) 2014 www.organizationalaesthetics.org The Values of Starchitecture: Commodification of Architectural Design in Contemporary Cities Davide Ponzini Politecnico di Milano Abstract In the last two decades international architects have been playing a significant role in city- branding and in marketing real estate products. Both public and private decision makers raised great expectations toward the increase in the value of the buildings and places that star architects designed and toward positive urban and economic effects that could derive from such projects (e.g. new and spectacular museum facilities, corporation headquarters). This paper criticizes the simplistic views representing the starchitect’s alleged added-value in mere economic terms and it proposes to consider a broader set of cultural and political dimensions. -

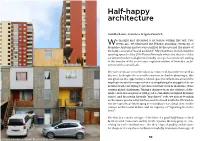

Half-Happy Architecture

Half-happy architecture Camillo Boano, Francisco Vergara Perucich e thought and discussed a lot before writing this text. Few Wweeks ago, we witnessed the Pritzker awarding ceremony of Alejandro Aravena and we were puzzled by the use and the abuse of the buzz-concept of “social architect”. After that then, we followed the opening speech of the 2016 Venice Biennale where the rhetoric of the social turn has been displaced, literally, on top of a metal scale staring to the frontier of the yet to come experimentation of formalist archi- tecture with a social look. The two events are not to be taken as connected, but rather treated as discrete. So despite the several hesitations we had in planning it, this text gives us the opportunity to develop some reflections around the implications and the reasons for not simplifying the struggle of those architects who are trying to produce relevant work in the frame of the current global challenges. Taking a distance from the critique of Ale- jandro Aravena as a person with good social skills (as argued by many critics) and his media-friendly “starchitect” role, we aim at focusing on the space produced by his firm and its overall aesthetic. We wish to rise two specific points hoping to contribute to a critical view on the current architectural debate and its capacity of “reporting from the front”. The first is a concise critique of the idea of a good-half-house coined by Elemental (Aravena’s studio) for the Quinta Monroy project, con- testing its real contribution to the idea of good quality architecture for the poor. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2017-2332

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: LNG2014-1176 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2017-2332 The Phenomenon of Being Distinguished in Architecture; a Study on Pritzker Prize Burcin Basyazici PhD Candidate Istanbul Technical University Turkey Belkis Uluoglu Professor Istanbul Technical University Turkey 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2017-2332 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. This paper has been peer reviewed by at least two academic members of ATINER. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research This paper should be cited as follows: Basyazici, B. and Uluoglu, B. (2017). "The Phenomenon of Being Distinguished in Architecture; a Study on Pritzker Prize", Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: ARC2017-2332. Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN: 2241-2891 27/11/2017 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2017-2332 The Phenomenon of Being Distinguished in Architecture; a Study on Pritzker Prize Burcin Basyazici Belkis Uluoglu Abstract The origin of architecture can be discussed based on the need of shelter and/or noble desire and it is thought that independent of its period, aim, function or audience; architecture, as a profession has desired to reach that which is unique within its definitive context. -

W Magazine September, 2010

W Magazine September, 2010 The Closet Starchitect She has designed icons and won the Pritzker, and is curating this fall's Venice ArChitecture Biennale. So why don't you know her name? Arthyr Lubow Analytic and poetic, assertive and recessive, Kazuyo Sejima is the moonwalker of architecture, gliding in opposite directions with mindbending grace. In 2004 the Tokyo-based firm SANAA, which she and Ryue Nishizawa had formed less than a decade earlier, catapulted onto the world scene with the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, in Kanazawa, a city on the Sea of Japan. Winning the Golden Lion at that year's Venice Architecture Biennale, the museum placed SANAA and Kanazawa on the map of contemporary culture. As SANAA went on to complete increasingly prestigious commissions, including the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, Sejima herself remained as hard to pin down as her architecture. In both her buildings and her manner, she is the opposite of that other prominent female architect, Zaha Hadid. Sejima dresses, speaks, and works in a way that deliberately deflects attention. So it is with ambivalence that Sejima has responded to a year that thrust her into the spotlight. In the spring she and Nishizawa were awarded architecture's highest honor, the Pritzker Prize. They also saw the inauguration of the Rolex Learning Center, a library and student complex in Lausanne, Switzerland, that happens to be their most audaciously attention-grabbing building to date. And this fall Sejima-on her own-is curating the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale. When she was offered the position, Sejima responded typically by asking if she and Nishizawa could be codirectors. -

Brand-New Cities: Frank Gehry's Bilbao Effect Looks a Lot Like 1960S-Style Urban Renewal Author(S): Wayne Curtis Source: the American Scholar, Vol

Architecture: Brand-New Cities: Frank Gehry's Bilbao Effect looks a lot like 1960s-style urban renewal Author(s): Wayne Curtis Source: The American Scholar, Vol. 75, No. 1 (Winter 2006), pp. 113-116 Published by: The Phi Beta Kappa Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41222543 . Accessed: 23/07/2013 16:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Phi Beta Kappa Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Scholar. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 132.206.27.24 on Tue, 23 Jul 2013 16:07:48 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Arts Architecture Brand-New Cities FrankGehry's Bilbao Effect looks a lotlike lgßOs-style urban renewal By Wayne Curtis he was eightyears old, the It's evidentlyno longerenough for a cityto futurearchitect Frank Gehry and havea definingsingle icon or a richlytextured hismother paid a visitto the Art Gal- andcomplex history. Itnow must have a brand, leryof Ontario in Toronto. It was within these completewith a strategyto implementit. hushedhalls thatGehry made a discovery: TheToronto Branding Project spent tens of somethingcalled art existed, and art was some- thousandsof dollarsdeveloping and promot- thinghe shouldstrive to ing BrandToronto (this makepart of his life. -

Today's News - October 5, 2006 a "Somewhat Cryptic" Reason Why There Will Be No Jail by Holl for Denver

Home Yesterday's News Calendar Contact Us Subscribe Today's News - October 5, 2006 A "somewhat cryptic" reason why there will be no jail by Holl for Denver. -- A bit too much history (and granite) dulls Miami's new Carnival Center. -- High hopes that new look for New York's Queens Museum will be eye-catching. -- High hopes for new mall in Plymouth, UK (but is the design already 10 years out of date?). -- In Warsaw, "a preservation battle with a post-totalitarian twist." -- Hume offers some insights to those considering entering Nathan Phillips Square competition. -- Pei returns to his roots with opening of Suzhou Museum tomorrow. -- Star Wars lucre from Lucas behind new film school complex for USC. -- You, too, can hang with U2 in Dublin's new twisting tower. -- Rybczynski rhapsodizes about America's first woman starchitect. -- Chicago Art Institute raids Van Alen for new curator of design. -- Month-long Toronto TRASH festival launches tonight with Rochon and Bélanger Q&A about ruin, reclamation, and trash. -- Kunsthalle Helsinki launches major Saarinen exhibition on international tour. ----- EDITOR'S NOTE: ANN is on the road and Internet access may be spotty...we'll do our best to post daily. To subscribe to the free daily newsletter click here Jail project loses an architect: Denver architectural firm klipp announced Wednesday that it and its partner, Steven Holl Architects, have parted ways. The reason given was somewhat cryptic.- Rocky Mountain News (Denver) Miami's Carnival Center Has Granite, Patron, Too Much History: ...gray granite reads like mashed potatoes whipped into runny peaks..