Comprehensive Plan Subcommittee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrating Infill Planning in California's General

Integrating Infill Planning in California’s General Plans: A Policy Roadmap Based on Best-Practice Communities September 2014 Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE)1 University of California Berkeley School of Law 1 This report was researched and authored by Christopher Williams, Research Fellow at the Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law. Ethan Elkind, Associate Director of Climate Change and Business Program at CLEE, served as project director. Additional contributions came from Terry Watt, AICP, of Terrell Watt Planning Consultant, and Chris Calfee, Senior Counsel; Seth Litchney, General Plan Guidelines Project Manager; and Holly Roberson, Land Use Council at the California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR), among other stakeholder reviewers. 1 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 Land Use Element ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Find and prioritize infill types most appropriate to your community .......................................... 5 1.2 Make an inclusive list of potential infill parcels, including brownfields ....................................... 9 1.3 Apply simplified mixed-use zoning designations in infill priority areas ...................................... 10 1.4 Influence design choices to -

How Built Environment Affects Travel Behavior

http://jtlu.org . 5 . 3 [2012] pp. 40–52 doi: 10.5198/jtlu.v5i3.266 How built environment affects travel behavior: A comparative analysis of the con- nections between land use and vehicle miles traveled in US cities Lei Zhang Jinhyun Hong Arefeh Nasri Qing Shen (corresponding author) University of University of Maryland University of University of Marylanda Washington Washington Abstract: Mixed findings have been reported in previous research regarding the impact of built environment on travel behavior—i.e., sta- tistically and practically significant effects found in a number of empirical studies and insignificant correlations shown in many other studies. It is not clear why the estimated impact is stronger or weaker in certain urban areas and how effective a proposed land use change/policy will be in changing certain travel behavior. This knowledge gap has made it difficult for decision makers to evaluate land use plans and policies according to their impact on vehicle miles traveled (VMT), and consequently, their impact on congestion mitigation, energy conservation, and pollution and greenhouse gas emission reduction. This research has several objectives: (1) re-examine the effects of built-environment factors on travel behavior, in particular, VMT in five US metropolitan areas grouped into four case study areas; (2) develop consistent models in all case study areas with the same model specifica- tion and datasets to enable direct comparisons; (3) identify factors such as existing land use characteristics and land use policy decision-making processes that may explain the different impacts of built environment on VMT in different urban areas; and (4) provide a prototype tool for government agencies and decision makers to estimate the impact of proposed land use changes on VMT. -

Infill Development Standards and Policy Guide

Infill Development Standards and Policy Guide STUDY PREPARED BY CENTER FOR URBAN POLICY RESEARCH EDWARD J. BLOUSTEIN SCHOOL OF PLANNING & PUBLIC POLICY RUTGERS, THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW JERSEY NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY with the participation of THE NATIONAL CENTER FOR SMART GROWTH RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND COLLEGE PARK, MARYLAND and SCHOOR DEPALMA MANALAPAN, NEW JERSEY STUDY PREPARED FOR NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY AFFAIRS (NJDCA) DIVISION OF CODES AND STANDARDS and NEW JERSEY MEADOWLANDS COMMISSION (NJMC) NEW JERSEY OFFICE OF SMART GROWTH (NJOSG) June, 2006 DRAFT—NOT FOR QUOTATION ii CONTENTS Part One: Introduction and Synthesis of Findings and Recommendations Chapter 1. Smart Growth and Infill: Challenge, Opportunity, and Best Practices……………………………………………………………...…..2 Part Two: Infill Development Standards and Policy Guide Section I. General Provisions…………………….…………………………….....33 II. Definitions and Development and Area Designations ………….....36 III. Land Acquisition………………………………………………….……40 IV. Financing for Infill Development ……………………………..……...43 V. Property Taxes……………………………………………………….....52 VI. Procedure………………………………………………………………..57 VII. Design……………………………………………………………….…..68 VIII. Zoning…………………………………………………………………...79 IX. Subdivision and Site Plan…………………………………………….100 X. Documents to be Submitted……………………………………….…135 XI. Design Details XI-1 Lighting………………………………………………….....145 XI-2 Signs………………………………………………………..156 XI-3 Landscaping…………………………………………….....167 Part Three: Background on Infill Development: Challenges -

Filling in the Spaces: Ten Essentials for Successful Urban Infill Housing

Filling in the Spaces: Ten Essentials for Successful Urban Infill Housing The Housing Partnership November, 2003 Made possible, in part, through a contribution from the Washington Association of Realtors This publication was prepared by The Housing Partnership, through a contribution from the Washington Association of Realtors. The Housing Partnership is a non-profit organization (officially known as the King County Housing Alliance) is dedicated to increasing the supply of affordable market rate housing in King County. This is achieved, in part, through policies of local government that foster increased housing development while preserving affordability and neighborhood character. The Partnership pursues these goals by: (a) building public awareness of housing affordability issues; (b) promoting design and regulatory solutions; and (c) acting as a convener of public, private and community leaders. Contact: Michael Luis, 425-453-5123, [email protected]. The 17,000-member Washington Association of REALTORS® represents 150,000 homebuyers each year, and the interests of more than 4 million homeowners throughout the state. REALTORS® are committed to improving our quality of life by supporting quality growth that encourages economic vitality, provides a variety of housing opportunities, builds better communities with good schools and safe neighborhoods, preserves the environment for our children, and protects property owners ability to own, use, buy and sell real property. Contact: Bryan Wahl, 1-800-562-6024, [email protected]. Cover photo: Ravenna Cottages. Developed by Threshold Housing. Filling in the Spaces: Ten Essentials for Successful Urban Infill Housing A growth management strategy that relies on extensive urban infill requires major changes from past industry and regulatory practice. -

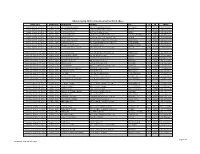

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

Smart Growth and Economic Success: Investing in Infill Development

United States February 2014 Environmental Protection www.epa.gov/smartgrowth Agency SMART GROWTH AND ECONOMIC SUCCESS: INVESTING IN INFILL DEVELOPMENT Office of Sustainable Communities Smart Growth Program Acknowledgments This report was prepared by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Sustainable Communities with the assistance of Renaissance Planning Group and RCLCO under contract number EP-W-11-009/010/11. Christopher Coes (Smart Growth America); Alex Barron (EPA Office of Policy); Dennis Guignet and Robin Jenkins (EPA National Center for Environmental Economics); and Kathleen Bailey, Matt Dalbey, Megan Susman, and John Thomas (EPA Office of Sustainable Communities) provided editorial reviews. EPA Project Leads: Melissa Kramer and Lee Sobel Mention of trade names, products, or services does not convey official EPA approval, endorsement, or recommendation. This paper is part of a series of documents on smart growth and economic success. Other papers in the series can be found at www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/economic_success.htm. Cover photos and credits: La Valentina in Sacramento, California, courtesy of Bruce Damonte; Small-lot infill in Washington, D.C., courtesy of EPA; The Fitzgerald in Baltimore, courtesy of The Bozzuto Group; and The Maltman Bungalows in Los Angeles, courtesy of Civic Enterprise Development. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ i I. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... -

R117.2019 STOMSA01 Sherritt Moa 43-101 Technical Report Effective Date 31 December 2018 Report Signature Date 6 June 2019 Report Status Final

kelIts NI 43-101 TECHNICAL REPORT Moa Nickel Project, Cuba CSA Global Report Nº R117.2019 Effective Date: 31 December 2018 Signature Date: 6 June 2019 www.csaglobal.com Qualified Persons Michael Elias , FAusIMM (CSA Global) Paul O’Callaghan , FAusIMM (CSA Global) Adrian Martinez , P.Geo (CSA Global) Kelvin Buban , P. Eng. (Sherritt International Corporation) SHERRITT INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION MOA NICKEL PROJECT – NI 43-101 TECHNICAL REPORT Report prepared for Client Name Sherritt International Corporation Project Name/Job Code STO.MSA.01v1 Contact Name Kelvin Buban Contact Title Director of Operations Support Office Address 8301-113 Street, Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta T8L 4K7 Report issued by CSA Global Pty Ltd Level 2, 3 Ord Street West Perth, WA 6005 AUSTRALIA PO Box 141 CSA Global Office West Perth WA 6872 AUSTRALIA T +61 8 9355 1677 F +61 8 9355 1977 E [email protected] Division Mining Report information Filename R117.2019 STOMSA01 Sherritt Moa 43-101 Technical Report Effective Date 31 December 2018 Report Signature Date 6 June 2019 Report Status Final Author and Qualified Person Signatures Coordinating Michael Elias [“Signed”] Author and BSc (Hons), MAIG, FAusIMM Signature: {Michael Elias} Qualified Person CSA Global Pty Ltd at Perth, Australia Paul O’Callaghan [“Signed”] Co-author and BEng (Mining), FAusIMM Signature: {Paul O’Callaghan} Qualified Person CSA Global Pty Ltd at Perth, Australia Dr. Adrian Martinez Vargas [“Signed & Sealed”] Co-author and PhD., P.Geo. (BC, ON) Signature: {Adrian Martinez Vargas} Qualified Person CSA Global Pty Ltd at Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Kelvin Buban [“Signed & Sealed”] Co-author and BSc. Chem. Eng., P.Eng. -

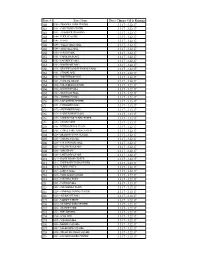

Radio Shack Closing Locations

Radio Shack Closing Locations Address Address2 City State Zip Gadsden Mall Shop Ctr 1001 Rainbow Dr Ste 42b Gadsden AL 35901 John T Reid Pkwy Ste C 24765 John T Reid Pkwy #C Scottsboro AL 35768 1906 Glenn Blvd Sw #200 - Ft Payne AL 35968 3288 Bel Air Mall - Mobile AL 36606 2498 Government Blvd - Mobile AL 36606 Ambassador Plaza 312 Schillinger Rd Ste G Mobile AL 36608 3913 Airport Blvd - Mobile AL 36608 1097 Industrial Pkwy #A - Saraland AL 36571 2254 Bessemer Rd Ste 104 - Birmingham AL 35208 Festival Center 7001 Crestwood Blvd #116 Birmingham AL 35210 700 Quintard Mall Ste 20 - Oxford AL 36203 Legacy Marketplace Ste C 2785 Carl T Jones Dr Se Huntsville AL 35802 Jasper Mall 300 Hwy 78 E Ste 264 Jasper AL 35501 Centerpoint S C 2338 Center Point Rd Center Point AL 35215 Town Square S C 1652 Town Sq Shpg Ctr Sw Cullman AL 35055 Riverchase Galleria #292 2000 Riverchase Galleria Hoover AL 35244 Huntsville Commons 2250 Sparkman Dr Huntsville AL 35810 Leeds Village 8525 Whitfield Ave #121 Leeds AL 35094 760 Academy Dr Ste 104 - Bessemer AL 35022 2798 John Hawkins Pky 104 - Hoover AL 35244 University Mall 1701 Mcfarland Blvd #162 Tuscaloosa AL 35404 4618 Hwy 280 Ste 110 - Birmingham AL 35243 Calera Crossing 297 Supercenter Dr Calera AL 35040 Wildwood North Shop Ctr 220 State Farm Pkwy # B2 Birmingham AL 35209 Center Troy Shopping Ctr 1412 Hwy 231 South Troy AL 36081 965 Ann St - Montgomery AL 36107 3897 Eastern Blvd - Montgomery AL 36116 Premier Place 1931 Cobbs Ford Rd Prattville AL 36066 2516 Berryhill Rd - Montgomery AL 36117 2017 280 Bypass -

CREATING an EQUITABLE INFILL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK for KERN COUNTY: Analysis and Community Recommendations to Support the 2019 General Plan Update

CREATING AN EQUITABLE INFILL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK FOR KERN COUNTY: Analysis and community recommendations to support the 2019 General Plan Update POLICY BRIEF APRIL 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AUTHORS Anisha Hingorani, Policy and Research Analyst, Advancement Project California Jacky Guerrero, Senior Policy & Research Analyst, Advancement Project California Adeyinka Glover, Esq., Attorney, Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability Chris Ringewald, Director of Research and Data Analysis, Advancement Project California PHOTO CREDIT: Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability WITH DEEPEST THANKS TO OUR TEAM AND PARTNERS FOR OFFERING YOUR INVALUABLE EXPERTISE THROUGHOUT THIS PROJECT: Michael Russo, Director of Equity in Community Investments, Advancement Project California Daniel Wherley, Senior Policy & Research Analyst, Advancement Project California Katie Smith, Director of Communications, Advancement Project California John Joanino, Senior Communications Associate, Advancement Project California Leslie Poston, Grant and Writing Consultant, Advancement Project California Ebonye Gussine Wilkins, Chief Executive Officer, Inclusive Media Solutions Jasmene Del Aguila, Policy Advocate, Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability Phoebe Seaton, Co-Founder And Co-Director And Legal Director, Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability Veronica Garibay, Co-Founder And Co-Director, Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability Gustavo Aguirre, Director of Organizing, Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment Chelsea Tu, -

Dillard's Spring 2012 In-Store Event List for ECCO Shoes

Dillard's Spring 2012 In-Store Event List for ECCO Shoes EVENT DATE EVENT TIMES STORE NAME ADDRESS CITY ST ZIP PHONE Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM COLUMBIANA CENTRE 100 COLUMBIANA CIRCLE COLUMBIA SC 29212 803-732-7037 Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM COASTLAND CENTER 1798 TAMIAMI TRAIL NORTH NAPLES FL 34102 239-261-4100 Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM COCONUT POINT 8017 VIA SARDINIA WAY ESTERO FL 33928 239-947-4133 Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM ALTAMONTE MALL 451 E ALTAMONTE DR STE #1101 ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32701 407-830-1211 Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM MARKET STREET 4414 S. W. COLLEGE RD SUITE 700 OCALA FL 34474 352-629-9266 Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM MELBOURNE SQUARE 1700 W. NEW HAVEN AVE. SUITE 801 MELBOURNE FL 32904 321-676-1300 Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM SANTA ROSA MALL 300 MARY ESTHER BLVD SUITE 119 MARY ESTHER FL 32569 850-244-7111 Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM PEMBROKE LAKES MALL 11945 PINES BLVD PEMBROKE PINES FL 33026 954-450-8661 Friday, March 16, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM SHOPPES AT RIVER CROSS 5080 RIVERSIDE DRIVE SUITE 800 MACON GA 31210 478-474-4545 Saturday, March 17, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM HAYWOOD MALL BOX 508 700 HAYWOOD ROAD GREENVILLE SC 29607 864-987-9229 Saturday, March 17, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM MACARTHUR CENTER 200 MONTICELLO AVE NORFOLK VA 23510 757-622-6800 Saturday, March 17, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM INTERNATIONAL PLAZA 2223 N WESTSHORE BLVD TAMPA FL 33607 813-342-1220 Saturday, March 17, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM SOUTHGATE PLAZA 400 SOUTHGATE PLAZA SARASOTA FL 34239 941-955-2241 Saturday, March 17, 2012 10 AM - 6 PM EDISON MALL 4125 CLEVELAND AVE FT. -

Store # Store Name Dates Clinique Gift Is Running 140 3.3.17

Store # Store Name Dates Clinique Gift Is Running 140 0140 - TRIANGLE TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 141 0141 - CARY TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 143 0143 - ALAMANCE CROSSING 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 144 0144 - FOUR SEASONS 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 145 0145 - HANES 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 146 0146 - VALLEY HILLS MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 148 0148 - ASHEVILLE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 150 0150 - SOUTH PARK 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 151 0151 - CAROLINA PLACE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 152 0152 - EASTRIDGE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 153 0153 - NORTHLAKE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 156 0156 - WESTFIELD INDEPENDENCE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 161 0161 - CITADEL MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 162 0162 - NORTHWOOD MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 163 0163 - COASTAL GRAND 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 164 0164 - COLUMBIANA CENTRE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 166 0166 - HAYWOOD MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 167 0167 - WESTGATE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 168 0168 - ANDERSON MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 170 0170 - MACARTHUR CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 171 0171 - LYNNHAVEN MALL 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 172 0172 - GREENBRIER MALL 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 174 0174 - PATRICK HENRY MALL 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 176 0176 - SHORT PUMP TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 179 0179 - STONY POINT 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 201 0201 - INTERNATIONAL PLAZA 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 203 0203 - CITRUS PARK TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 204 0204 - BRANDON TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 205 0205 - TYRONE SQUARE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 206 0206 - COUNTRYSIDE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 207 0207 - GULFVIEW SQUARE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 208 0208 - WIREGRASS 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 209 0209 - LAKELAND SQUARE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 210 0210 - EAGLE RIDGE CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 213 0213 -

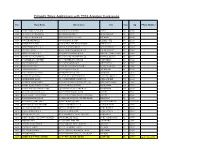

DILLARDS | Annalee Store List

Dillard's Store Addresses with 2018 Annalee Exclusives Store Store Name Address Line 2 City State Zip Phone Number 0141 CARY TOWNE CENTER 1105 WALNUT STREET CARY NC 27511 0143 ALAMANCE CROSSING 1003 BOSTON DRIVE BURLINGTON NC 27215 0146 VALLEY HILLS MALL 1930 US HIGHWAY 70 SE HICKORY NC 28602 0150 SOUTHPARK MALL 4400 SHARON ROAD CHARLOTTE NC 28211 0151 CAROLINA PLACE 11041 CAROLINA PLACE PKWY PINEVILLE NC 28134 0156 INDEPENDENCE MALL 3500 OLEANDER DRIVE WILMINGTON NC 28403 0161 CITADEL MALL 2066 SAM RITTENBERG BLVD. CHARLESTON SC 29407 0162 NORTHWOOD MALL 2150 NORTHWOODS BLVD NORTH CHARLESTON SC 29406 0163 COASTAL GRAND MALL 100 COASTAL GRAND CIRCLE MYRTLE BEACH SC 29577 0164 COLUMBIANA CENTRE 100 COLUMBIANA CIRCLE COLUMBIA SC 29212 0166 HAYWOOD MALL 700 HAYWOOD ROAD GREENVILLE SC 29607 0167 WESTGATE MALL 205 W. BLACKSTOCK ROAD SPARTANBURG SC 29301 0168 ANDERSON MALL 3101 N.MAIN SUITE D ANDERSON SC 29621 0170 MACARTHUR CENTER 200 MONTICELLO AVE NORFOLK VA 23510 0171 LYNNHAVEN MALL 701 LYNNHAVEN PARKWAY VIRGINIA BEACH VA 23452 0172 GREENBRIER MALL 1401 GREENBRIER PARKWAY CHESAPEAKE VA 23320 0174 PATRICK HENRY MALL 12300 JEFFERSON AVENUE STE 300 NEWPORT NEWS VA 23602 0176 SHORT PUMP TOWN CENTER 11824 W BROAD STREET RICHMOND VA 23233 0179 STONY POINT FASHION PARK 9208 STONY POINT PARKWAY RICHMOND VA 23235 0201 INTERNATIONAL PLAZA 2223 N WESTSHORE BLVD TAMPA FL 33607 0203 WESTFIELD CITRUS PARK 8161 CITRUS PARK TOWN CTR MALL TAMPA FL 33625 0204 WESTFIELD BRANDON 303 BRANDON TOWN CENTER MALL BRANDON FL 33511 0205 TYRONE SQUARE MALL 6990 TYRONE SQUARE ST. PETERSBURG FL 337103936 0206 WESTFIELD COUNTRYSIDE 27001 US HIGHWAY 19 N CLEARWATER FL 33761 0207 GULFVIEW SQUARE 9409 U.S.