The Movement Against CAFTA in Costa Rica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distritos Declarados Zona Catastrada.Xlsx

Distritos de Zona Catastrada "zona 1" 1-San José 2-Alajuela3-Cartago 4-Heredia 5-Guanacaste 6-Puntarenas 7-Limón 104-PURISCAL 202-SAN RAMON 301-Cartago 304-Jiménez 401-Heredia 405-San Rafael 501-Liberia 508-Tilarán 601-Puntarenas 705- Matina 10409-CHIRES 20212-ZAPOTAL 30101-ORIENTAL 30401-JUAN VIÑAS 40101-HEREDIA 40501-SAN RAFAEL 50104-NACASCOLO 50801-TILARAN 60101-PUNTARENAS 70501-MATINA 10407-DESAMPARADITOS 203-Grecia 30102-OCCIDENTAL 30402-TUCURRIQUE 40102-MERCEDES 40502-SAN JOSECITO 502-Nicoya 50802-QUEBRADA GRANDE 60102-PITAHAYA 703-Siquirres 106-Aserri 20301-GRECIA 30103-CARMEN 30403-PEJIBAYE 40104-ULLOA 40503-SANTIAGO 50202-MANSIÓN 50803-TRONADORA 60103-CHOMES 70302-PACUARITO 10606-MONTERREY 20302-SAN ISIDRO 30104-SAN NICOLÁS 306-Alvarado 402-Barva 40504-ÁNGELES 50203-SAN ANTONIO 50804-SANTA ROSA 60106-MANZANILLO 70307-REVENTAZON 118-Curridabat 20303-SAN JOSE 30105-AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 30601-PACAYAS 40201-BARVA 40505-CONCEPCIÓN 50204-QUEBRADA HONDA 50805-LIBANO 60107-GUACIMAL 704-Talamanca 11803-SANCHEZ 20304-SAN ROQUE 30106-GUADALUPE O ARENILLA 30602-CERVANTES 40202-SAN PEDRO 406-San Isidro 50205-SÁMARA 50806-TIERRAS MORENAS 60108-BARRANCA 70401-BRATSI 11801-CURRIDABAT 20305-TACARES 30107-CORRALILLO 30603-CAPELLADES 40203-SAN PABLO 40601-SAN ISIDRO 50207-BELÉN DE NOSARITA 50807-ARENAL 60109-MONTE VERDE 70404-TELIRE 107-Mora 20307-PUENTE DE PIEDRA 30108-TIERRA BLANCA 305-TURRIALBA 40204-SAN ROQUE 40602-SAN JOSÉ 503-Santa Cruz 509-Nandayure 60112-CHACARITA 10704-PIEDRAS NEGRAS 20308-BOLIVAR 30109-DULCE NOMBRE 30512-CHIRRIPO -

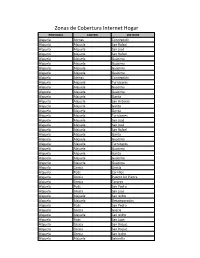

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Mapa De Valores De Terrenos Por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 4

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 4 HEREDIA CANTÓN 03 SANTO DOMINGO 488200 491200 494200 497200 Mapa de Valores de Terrenos Centro Urbano de Santo Domingo por Zonas Homogéneas ESCALA 1:5.000 490200 Barva n Provincia 4 Heredia Avenida 9 CALLE RONDA 2 C RESIDENCIAL VEREDA REAL a SAN VICENTE URBANIZACION LA COLONIA l l Cantón 03 Santo Domingo 4 03 06 U01 4 03 02 U11 e 4 03 02 U06 CALLE RONDA 3 Exofisa LA BASILICA La Casa de los Precios Bajos 4 03 01 U03 4 03 02 U10 Grupo A.A de an l r 1107400 G 1107400 C a ra n a a P a l ío Repuestos Yosomi l Av e C Bar Las Juntas R enida 5 L a San Rafael F o r r a CRUZ ROJA Restaurante El Primero d Qu i n s eb ra s d c a a G I 4 03 01 U02 j u Av ac e La Cruz Roja enida 5 a al Parqueo Plaza Nueva n San Isidro s Ministerio de Hacienda L a a o S i Ave Banco Popular R nida 3 A Abastecedor El Trébol Órgano de Normalización Técnica Tienda Anais os Biblioteca Municipal 9 r Robledales Country House Basílica Santo Domingo de Guzmán lle e a l b Estación de Bomberos G l a a C le C l Plaza de Fútbol de Santo Domingo Ca 4 03 04 R03/U03 o Coope Pará l A l venida 1 i Oficina Parroquial r PlazaIglesia Católica de San Luis r G G a o C Escuela San Luis Gonzaga La Curacao t a s 04 o 5 i ñ a n o t Ru l a g Escuela Félix Arcadio Montero u 4 03 08 R01/U01 p a A r s n CALLE 9 e COMERCIAL E B Municipio d l A 3 veni 4 03 05 U01 a da Ce B.C.R ntral 4 03 01 U01 4 C n ristób e a l l Coló o n l 5 LA BASILICA i Salón Parroquial a c SANTA ROSA URBANO e C a l l 4 03 01 U04 Zapatería Santa Rosa G N 4 03 06 R03/U03 a 4 03 08 R02/U02 PARÁ a C r Iglesia El Rosario CONDOMINIO LOS HIDALGOS e t G e R 4 03 05 U02 r r í SANTO DOMINGO o a A Centro Educativo Santa María C Avenida 2 Condominio La Domingueña er g n Del Co et r m a Depósito San Carlos ercio lle P K-9 Ca Cementerio de San Luis R Banco Nacional u t a 3 C Industrias Zurquí 0 a 8 l l e E ZONA JUZGADO Y CORREO a m r Aprobado por: a 1103400 1103400 4 03 01 U05 i PARACITO l P i a o í SANTA ROSA 4 03 07 R06/U06 R s SANTO TOMÁS á b 6 i da T l i 6 x n Av ve e i nida A Calle La Canoa Ing. -

Otilio Ulate and the Traditional Response to Contemporary Political Change in Costa Rica

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1977 Otilio Ulate and the Traditional Response to Contemporary Political Change in Costa Rica. Judy Oliver Milner Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Milner, Judy Oliver, "Otilio Ulate and the Traditional Response to Contemporary Political Change in Costa Rica." (1977). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3127. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3127 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Mapa De Valores Del Terreno Por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 1 San José Cantón 01 San José Distrito 10 Hatillo

MAPA DE VALORES DEL TERRENO POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 1 SAN JOSÉ CANTÓN 01 SAN JOSÉ DISTRITO 10 HATILLO 487200 489200 Mapa de Valores del Terreno por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 1 San José 1098400 1098400 Cantón 01 San José Distrito 10 Hatillo DISTRITO MATA REDONDA Rio Tiribí Ministerio de Hacienda Órgano de Normalización Técnica Calle 3 DISTRITO HOSPITAL HATILLO 8-n BAJO CAÑADA A Hatillo 1 01 10 U16 HATILLO 8 Avenida Nosara Iglesia Hatillo 7 Plaza G A Hatillo Avenida Adolfo Marin Marte Avenida Juan Rafael Mora BAJO CAÑADA Avenida Tiribí Aprobado por: Calle 1 Los Aserrines Urb. La Loma Ing. Alberto Poveda Alvarado Director Tajo Avenida Nosara Órgano de Normalización Técnica Parque HATILLO 7 Iglesia María Reina Instituto Nacional de Aprendizaje (INA) HATILLO 2 G HATILLO 1 Mapa de Valores del Terreno Centro de Formación Taller Público Hatillo Colegio Brenes Mesen Avenida Villanea 1 01 10 U15 SAN JOSE n Avenida Nusara por Zonas Homogéneas Liceo Roberto Brenes Parque Provincia 1 San José Calle Joaquín Bernardo Calvo Centro Educativo n Cantón 01 San José HATILLO 1 Plaza TOPACIO HATILLO 2 Calle Tempisque Distrito 10 Hatillo Iglesia de Hatillo 6 1 01 10 U14 HATILLO G Esc. Manuel Belgrano Plaza n Río Tiribí Escuela de Hatillo 2 Av. Panamá n Plaza A Hatillo Escuela de Hatillo 2 Paseo Simón Bolívar n Bodegas OIJ Av. Nicaragua HATILLO 6 MÁS X MENOS C.C. Hatillo Plaza TOPACIO Avenida Andes Biblioteca Pública de Hatillo CENTRO COMERCIAL HATILLO Calle Francia SAGRADA FAMILIA 1 01 10 U13 SHELL HATILLOS 5 - 6 -7 1 01 10 U02 1 01 10 U11 SAGRADA FAMILIA Calle Costa Rica 1 01 10 U04 Av. -

1 Costa Rica's Policing of Sexuality and The

COSTA RICA’S POLICING OF SEXUALITY AND THE NORMALIZATION OF THE BOURGEOIS FAMILY By GRISELDA E. RODRIGUEZ A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 ©2010 Griselda E. Rodriguez 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For being an incredible source of ideas and advice, and for eternally changing my theoretical approach to history I would like to thank Dr. Mark Thurner. I am grateful to Dr. Richmond Brown for continuously having an open door policy and being a genuine source of intellectual comfort. To them and to Dr. Carmen Diana Deere I am in debt for their sincere suggestions, guidance, and patience during the lengthy process of thesis writing and my overall intellectual development. I would like to thank my mother, for being my deepest confidante and most fervent supporter; my father for reminding me of the importance of laughter during my moments of frustration; and my brother for being a never-ending source of advice and positivity. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................................... 3 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1 NATION, GENDER, AND MYTH ............................................................................................. 7 Costa Rica’s Exceptionalist Myth ............................................................................................. -

Morality, Equality and National Identity in Carmen Lyra's Cuentos De Mi Tía Panchita

MORALITY, EQUALITY AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN CARMEN LYRA'S CUENTOS DE MI TÍA PANCHITA by CATHERINE ELIZABETH BROOKS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MA by Research Department of Modern Languages, College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham February 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This study argues that Lyra used Cuentos de mi tía Panchita as a vehicle to promote her socio-educational vision, whilst also endorsing a distinctive national identity and strong moral messages. Stories are examined for themes including Costa Rican national identity and the author's political ideology with particular reference to morality, and gender and class equality. Subversion of moral and patriarchal values is also explored. Moral contradictions are identified and discussed, leading to the conclusion that Lyra's work includes examples of both positive and negative behaviour. It is suggested that Lyra does not differentiate character traits or domestic situations based on gender stereotypes; her characters are equals. Furthermore, although some stories include various socio-economic groups, they also feature characters that transcend the different social classes. -

Plan De Desarrollo Distrital, Pocosol 2014-2024

Plan de Desarrollo Distrital, Pocosol 2014-2024 [0] Plan de Desarrollo Distrital Pocosol 2014-2024 Contenido AGRADECIMIENTO .............................................................................................................................. 7 PRESENTACIÓN .................................................................................................................................... 8 Miembros de la comisión del Plan de Desarrollo Municipal ............................................................. 10 1. INTRODUCCION ......................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 Naturaleza y Alcance del plan ................................................................................................. 13 1.1.1 Naturaleza ........................................................................................................................ 13 1.1.2 Alcance ............................................................................................................................. 13 2. ASPECTOS GENERALES DEL CANTON ........................................................................................ 16 2.1 Antecedentes sobre su creación, localización geográfica y límites ........................................ 16 2.2 Reseña Histórica ..................................................................................................................... 18 2.2.1 De Distrito a Cantón ...................................................................................................... -

La Oposición Antitrujillista, La Legión Del Caribe Y José Figueres De Costa Rica (1944-1949) 1 María Dolores Ferrero Universidad De Huelva [email protected]

La oposición antitrujillista, la Legión del Caribe y José Figueres de Costa Rica (1944-1949) 1 María Dolores Ferrero Universidad de Huelva [email protected] Matilde Eiroa Universidad Carlos III de Madrid [email protected] Recepción: 27 de octubre de 2014 / Revisión: 19 de marzo de 2015 Aceptación: 28 de abril de 2015 / Publicación: Diciembre de 2016 Resumen En la década de 1940, los exiliados dominicanos, junto a otros centroamericanos, se unieron en la orga- nización denominada Legión del Caribe con el objetivo de apoyarse mutuamente contra las dictaduras. Acordaron comenzar la lucha contra Trujillo y Somoza, pero la coyuntura aconsejó posponer los planes iniciales y se implicaron en la guerra civil o revolución de Costa Rica de 1948. Los dominicanos Horacio Ornes y Juan Rodríguez dirigieron la activa participación en el conflicto que terminaría con la toma del poder por José Figueres (presidente de facto de 1948 a 1949), que no hubiera sido posible sin la Legión del Caribe. Sin embargo, José Figueres no asumió posteriormente su compromiso con la Legión y las reclamaciones dominicanas nunca se atendieron. Palabras clave: Legión del Caribe, dictaduras centroamericanas, José Figueres, Rafael L. Trujillo, Anastasio Somoza, Caribe, Siglo XX. The Anti-Trujillo Opposition, the Caribbean Legion and Costa Rica’s Jose Figueres (1944-1949) Abstract In the 1940’s, exiled Dominicans and other Central-Americans joined together in an organization called the Caribbean Legion, with the objective of providing mutual support in the struggle against dictator- ship. They began by agreeing to fight against Trujillo and Somoza, but circumstances favored the pos- tponement of their initial plans, and their involvement in the Civil War or Revolution of Costa Rica of 1948 instead. -

Mapa De Valores De Terrenos Por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 2 Alajuela Cantón 09 Orotina

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 2 ALAJUELA CANTÓN 09 OROTINA 426000 428500 431000 433500 436000 438500 441000 443500 446000 448500 Mapa de Valores de Terrenos 1101000 1101000 por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 2 Alajuela Cantón 09 Orotina San Mateo Quebrada Fresca Urb. Vistas Del Mar Atenas 2 09 03 R05/U05 Concepción Ministerio de Hacienda Desarrollo Vista Mar Río Concepción Esparza Quebrada Salitral Órgano de Normalización Técnica 1098500 2 09 03 R06 1098500 Quebrada Pital Zona de Protección Cerro Chompipe Brumas del Machuca Urb. La Moderna Mateo San A 2 09 03 R03 2 09 01 R38/U38 2 09 03 R09/U09 HACIENDA VIEJA Plaza Cabañas Las Cigarras Río Machuca 2 09 01 R34/U34 2 09 01 R06/U06 Urb. Juan Araya I 2 09 03 R04 2 09 05 R07 A Atenas 2 09 01 R33/U33 Quebrada Santo Domingo nm Proyecto Las Veraneras Urb. Hacienda Nueva æ Antiguo Zoológico Barrio Las Cabras 2 09 01 U05 Tajo Calera Dantas Hacienda Vieja 2 09 03 U07 Ruta Nacional 27 Campamento Adventista Escuela 2 09 01 R32/U32 Quebrada Vizcaíno nm 2 09 03 R01/U01 2 09 02 U12 æ 2 09 01 R07/U07 Barrio La Alumbre 2 09 01 R04/U04 2 09 03 R02/U02 2 09 05 R08/U08 2 09 02 R11/U11 2 09 02 R03/U03 Guayabal Ermita Agregados Río Grande Río Jesus María æ Quebrada Rastro EL MASTATE 2 09 01 U36 Barrio Jesús 2 09 02 U01 2 09 01 U03 2 09 02 U05 2 09 01 U27 Quebrada Ceiba 2 09 01 nmU31 Calle Los Meza 2 09 01 R08/U08 A Caldera nm nm Palí Quebrada Grande 2 09 01 U02 Salón Comunal Quebrada Guayabal æ 2 09 02 R02/U02 2 09 02 U06 2 09 01 U23 Poliducto 2 09 01 U01 2 09 01 R09/U09 2 09 03 R08/U08 2 09 01 U10 Aprobado por: 2 09 01 U30 2 09 01 U28 æ 2 09 01nm U26 nm nm 1096000 2 09 01 R29/U29 2 09 01nm U22 2 09 nm01 U11 1096000 Plaza 2 09 01 U24 RADA an APM Terminals Company Urb. -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF JULY 2018 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3024 015571 ALAJUELA COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 54 0 0 0 0 0 54 3024 015572 CARTAGO COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 40 0 0 0 0 0 40 3024 015573 CIUDAD QUESADA COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 58 0 0 0 0 0 58 3024 015577 CURRIDABAT COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 31 0 0 0 0 0 31 3024 015578 DESAMPARADOS COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 57 0 0 0 0 0 57 3024 015579 ESCAZU COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 21 0 0 0 -1 -1 20 3024 015582 GRECIA COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 63 0 0 0 0 0 63 3024 015583 GUADALUPE COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 29 0 0 0 -3 -3 26 3024 015584 HEREDIA COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 35 0 1 0 0 1 36 3024 015586 LIBERIA COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 46 0 0 0 0 0 46 3024 015589 MORAVIA COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 50 0 0 0 0 0 50 3024 015590 OROTINA COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 17 0 0 0 0 0 17 3024 015593 PUNTARENAS COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 24 0 0 0 0 0 24 3024 015594 PURISCAL COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 18 0 0 0 0 0 18 3024 015597 SAN JOSE COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 29 0 0 0 0 0 29 3024 015598 SAN ISIDRO DE EL GENERAL COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 32 1 0 0 0 1 33 3024 015601 SANTO DOMINGO COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 36 0 0 0 0 0 36 3024 015603 TIBAS COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 68 0 0 0 0 0 68 3024 015606 TURRIALBA COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 17 0 0 0 -2 -2 15 3024 029639 SAN JOSE HATILLO COSTA RICA D 4 4 07-2018 12 0 0 0 0 0 12 3024 030637 SAN JOAQUIN