What Are Some Non-Verbal Signs of Pain?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict, Arousal, and Logical Gut Feelings

CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Wim De Neys1, 2, 3 1 ‐ CNRS, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 2 ‐ Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 3 ‐ Université de Caen Basse‐Normandie, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France Mailing address: Wim De Neys LaPsyDÉ (Unité CNRS 3521, Université Paris Descartes) Sorbonne - Labo A. Binet 46, rue Saint Jacques 75005 Paris France [email protected] ABSTRACT Although human reasoning is often biased by intuitive heuristics, recent studies on conflict detection during thinking suggest that adult reasoners detect the biased nature of their judgments. Despite their illogical response, adults seem to demonstrate a remarkable sensitivity to possible conflict between their heuristic judgment and logical or probabilistic norms. In this chapter I review the core findings and try to clarify why it makes sense to conceive this logical sensitivity as an intuitive gut feeling. CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Imagine you’re on a game show. The host shows you two metal boxes that are both filled with $100 and $1 dollar bills. You get to draw one note out of one of the boxes. Whatever note you draw is yours to keep. The host tells you that box A contains a total of 10 bills, one of which is a $100 note. He also informs you that Box B contains 1000 bills and 99 of these are $100 notes. So box A has got one $100 bill in it while there are 99 of them hiding in box B. Which one of the boxes should you draw from to maximize your chances of winning $100? When presented with this problem a lot of people seem to have a strong intuitive preference for Box B. -

Panic Disorder Issue Brief

Panic Disorder OCTOBER | 2018 Introduction Briefings such as this one are prepared in response to petitions to add new conditions to the list of qualifying conditions for the Minnesota medical cannabis program. The intention of these briefings is to present to the Commissioner of Health, to members of the Medical Cannabis Review Panel, and to interested members of the public scientific studies of cannabis products as therapy for the petitioned condition. Brief information on the condition and its current treatment is provided to help give context to the studies. The primary focus is on clinical trials and observational studies, but for many conditions there are few of these. A selection of articles on pre-clinical studies (typically laboratory and animal model studies) will be included, especially if there are few clinical trials or observational studies. Though interpretation of surveys is usually difficult because it is unclear whether responders represent the population of interest and because of unknown validity of responses, when published in peer-reviewed journals surveys will be included for completeness. When found, published recommendations or opinions of national organizations medical organizations will be included. Searches for published clinical trials and observational studies are performed using the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database using key words appropriate for the petitioned condition. Articles that appeared to be results of clinical trials, observational studies, or review articles of such studies, were accessed for examination. References in the articles were studied to identify additional articles that were not found on the initial search. This continued in an iterative fashion until no additional relevant articles were found. -

Damages for Pain and Suffering

DAMAGES FOR PAIN AND SUFFERING MARCUS L. PLANT* THE SHAPE OF THE LAw GENERALLY It does not require any lengthy exposition to set forth the basic principles relating to the recovery of damages for pain and suffering in personal injury actions in tort. Such damages are a recognized element of the successful plaintiff's award.1 The pain and suffering for which recovery may be had includes that incidental to the injury itself and also 2 such as may be attributable to subsequent surgical or medical treatment. It is not essential that plaintiff specifically allege that he endured pain and suffering as a result of the injuries specified in the pleading, if his injuries stated are of such nature that pain and suffering would normally be a consequence of them.' It would be a rare case, however, in which plaintiff's counsel failed to allege pain and suffering and claim damages therefor. Difficult pleading problems do not seem to be involved. The recovery for pain and suffering is a peculiarly personal element of plaintiff's damages. For this reason it was held in the older cases, in which the husband recovered much of the damages for injury to his wife, that the injured married woman could recover for her own pain and suffering.4 Similarly a minor is permitted to recover for his pain 5 and suffering. No particular amount of pain and suffering or term of duration is required as a basis for recovery. It is only necessary that the sufferer be conscious.6 Accordingly, recovery for pain and suffering is not usually permitted in cases involving instantaneous death." Aside from this, how- ever,. -

Common Myths About the Joint Commission Pain Standards

T H S Y M Common myths about The Joint Commission pain standards Myth No. 1: The Joint Commission endorses pain as a vital sign. The Joint Commission never endorsed pain as a vital sign. Joint Commission standards never stated that pain needs to be treated like a vital sign. The roots of this misconception go back to 1990 (more than a decade before Joint Commission pain standards were released), when pain experts called for pain to be “made visible.” Some organizations tried to achieve this by making pain a vital sign. The only time the standards referenced the fifth vital sign was when examples were provided of how some organizations were assessing patient pain. In 2002, The Joint Commission addressed the problems of the fifth vital sign concept by describing the unintended consequences of this approach to pain management, and described how organizations subsequently modified their processes. Myth No. 2: The Joint Commission requires pain assessment for all patients. The original pain standards, which were applicable to all accreditation programs, stated “Pain is assessed in all patients.” This requirement was eliminated in 2009 from all programs except Behavioral Health Care. It was The Joint Commission thought that these patients were less able to bring up the fact that they were in pain and, therefore, required a more pain standards aggressive approach. The current Behavioral Health Care standard states, “The organization screens all patients • The hospital educates for physical pain.” The current standard for the hospital and other programs states, “The organization assesses and all licensed independent practitioners on assessing manages the patient’s pain.” This allows organizations to set their own policies regarding which patients should and managing pain. -

Psychosexual Characteristics of Vestibulodynia Couples: Partner Solicitousness and Hostility Are Associated with Pain

418 ORIGINAL RESEARCH—PAIN Psychosexual Characteristics of Vestibulodynia Couples: Partner Solicitousness and Hostility are Associated with Pain Mylène Desrosiers, MA,* Sophie Bergeron, PhD,* Marta Meana, PhD,† Bianca Leclerc, B.Sc.,* Yitzchak M. Binik, PhD,‡ and Samir Khalifé, MD§ *Department of Sexology, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; †Department of Psychology, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV, USA; ‡Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; §Jewish General Hospital—Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Montreal, Quebec, Canada DOI: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00705.x ABSTRACT Introduction. Provoked vestibulodynia is a prevalent yet misunderstood women’s sexual health issue. In particular, data concerning relationship characteristics and psychosexual functioning of partners of these women are scarce. Moreover, no research to date has examined the role of the partner in vestibulodynia. Aims. This study aimed to characterize and compare the psychosexual profiles of women with vestibulodynia and their partners, in addition to exploring whether partner-related variables correlated with women’s pain and associ- ated psychosexual functioning. Methods. Forty-three couples in which the woman suffered from vestibulodynia completed self-report question- naires focusing on their sexual functioning, dyadic adjustment, and psychological adjustment. Women were diagnosed using the cotton-swab test during a standardized gynecological examination. They also took part in a structured interview during which they were asked about their pain during intercourse and frequency of intercourse. They also completed a questionnaire about their perceptions of their partners’ responses to the pain. Main Outcome Measures. Dependent measures for both members of the couple included the Sexual History Form, the Locke-Wallace Marital Adjustment Scale and the Brief Symptom Inventory. -

Pain, Sadness, Aggression, and Joy: an Evolutionary Approach to Film Emotions

Pain, Sadness, Aggression, and Joy: An Evolutionary Approach to Film Emotions TORBEN GRODAL Abstract: Based on film examples and evolutionary psychology, this article dis- cusses why viewers are fascinated not only with funny and pleasure-evoking films, but also with sad and disgust-evoking ones. This article argues that al- though the basic emotional mechanisms are made to avoid negative experi- ences and approach pleasant ones, a series of adaptations modify such mechanisms. Goal-setting in narratives implies that a certain amount of neg- ative experiences are gratifying challenges, and comic mechanisms make it possible to deal with negative social emotions such as shame. Innate adapta- tions make negative events fascinating because of the clear survival value, as when children are fascinated by stories about loss of parental attachment. Furthermore, it seems that the interest in tragic stories ending in death is an innate adaptation to reaffirm social attachment by the shared ritual of sad- ness, often linked to acceptance of group living and a tribal identity. Keywords: attachment, cognitive film theory, coping and emotions, evolution- ary psychology, hedonic valence, melodrama, sadness, tragedy Why are viewers attracted to films that contain many negative experiences and endings? It seems counterintuitive that tragic stories can compete for our attention with stories that have a more upbeat content. The basic mechanisms underlying our experience with pleasure and displeasure, which psychologists call positive and negative hedonic valence, would seem to lead us to prefer beneficial and fitness-enhancing experiences and to avoid violent confronta- tion with harmful experiences. We are drawn to tasty food and attractive part- ners and retreat from enemies or bad tasting food. -

![Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9395/arxiv-2011-03588v1-cs-cl-6-nov-2020-1219395.webp)

Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020

Hostility Detection Dataset in Hindi Mohit Bhardwajy, Md Shad Akhtary, Asif Ekbalz, Amitava Das?, Tanmoy Chakrabortyy yIIIT Delhi, India. zIIT Patna, India. ?Wipro Research, India. fmohit19014,tanmoy,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Despite Hindi being the third most spoken language in the world, and a significant presence of Hindi content on social In this paper, we present a novel hostility detection dataset in Hindi language. We collect and manually annotate ∼ 8200 media platforms, to our surprise, we were not able to find online posts. The annotated dataset covers four hostility di- any significant dataset on fake news or hate speech detec- mensions: fake news, hate speech, offensive, and defamation tion in Hindi. A survey of the literature suggest a few works posts, along with a non-hostile label. The hostile posts are related to hostile post detection in Hindi, such as (Kar et al. also considered for multi-label tags due to a significant over- 2020; Jha et al. 2020; Safi Samghabadi et al. 2020); however, lap among the hostile classes. We release this dataset as part there are two basic issues with these works - either the num- of the CONSTRAINT-2021 shared task on hostile post detec- ber of samples in the dataset are not adequate or they cater tion. to a specific dimension of the hostility only. In this paper, we present our manually annotated dataset for hostile posts 1 Introduction detection in Hindi. We collect more than ∼ 8200 online so- The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives forever, cial media posts and annotate them as hostile and non-hostile both online and offline. -

On the Mutual Effects of Pain and Emotion: Facial Pain Expressions

PAINÒ 154 (2013) 793–800 www.elsevier.com/locate/pain On the mutual effects of pain and emotion: Facial pain expressions enhance pain perception and vice versa are perceived as more arousing when feeling pain ⇑ Philipp Reicherts a,1, Antje B.M. Gerdes b,1, Paul Pauli a, Matthias J. Wieser a, a Department of Psychology, Clinical Psychology, Biological Psychology, and Psychotherapy, University of Würzburg, Germany b Department of Psychology, Biological and Clinical Psychology, University of Mannheim, Germany Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article. article info abstract Article history: Perception of emotional stimuli alters the perception of pain. Although facial expressions are powerful Received 27 August 2012 emotional cues – the expression of pain especially plays a crucial role for the experience and communi- Received in revised form 15 December 2012 cation of pain – research on their influence on pain perception is scarce. In addition, the opposite effect of Accepted 5 February 2013 pain on the processing of emotion has been elucidated even less. To further scrutinize mutual influences of emotion and pain, 22 participants were administered painful and nonpainful thermal stimuli while watching dynamic facial expressions depicting joy, fear, pain, and a neutral expression. As a control con- Keywords: dition of low visual complexity, a central fixation cross was presented. Participants rated the intensity of Pain expression the thermal stimuli and evaluated valence and arousal of the facial expressions. In addition, facial elec- EMG Heat pain tromyography was recorded as an index of emotion and pain perception. Results show that faces per se, Mutual influences compared to the low-level control condition, decreased pain, suggesting a general attention modulation of pain by complex (social) stimuli. -

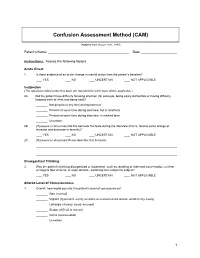

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Adapted from Inouye et al., 1990) Patient’s Name: Date: Instructions: Assess the following factors. Acute Onset 1. Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Inattention (The questions listed under this topic are repeated for each topic where applicable.) 2A. Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention (for example, being easily distractible or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said)? Not present at any time during interview Present at some time during interview, but in mild form Present at some time during interview, in marked form Uncertain 2B. (If present or abnormal) Did this behavior fluctuate during the interview (that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity)? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE 2C. (If present or abnormal) Please describe this behavior. Disorganized Thinking 3. Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable, switching from subject to subject? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Altered Level of Consciousness 4. Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness? Alert (normal) Vigilant (hyperalert, overly sensitive to environmental stimuli, startled very easily) Lethargic (drowsy, easily aroused) Stupor (difficult to arouse) Coma (unarousable) Uncertain 1 Disorientation 5. Was the patient disoriented at any time during the interview, such as thinking that he or she was somewhere other than the hospital, using the wrong bed, or misjudging the time of day? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Memory Impairment 6. -

RELATIONAL EMPATHY 1 Running Head

RELATIONAL EMPATHY 1 Running head: RELATIONAL EMPATHY The Interpersonal Functions of Empathy: A Relational Perspective Alexandra Main, Eric A. Walle, Carmen Kho, & Jodi Halpern Alexandra Main Carmen Kho University of California, Merced University of California, Merced 5200 N Lake Road 5200 N Lake Road Merced, CA 95343 Merced, CA 95343 Phone: 209-228-2429 Phone: 714-253-6163 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Eric A. Walle Jodi Halpern University of California, Merced University of California, Berkeley 5200 N Lake Road 570 University Hall Merced, CA 95343 Berkeley, CA 94720 Phone: 209-228-4634 Phone: 510-642-4366 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alexandra Main, Psychological Sciences, 5200 North Lake Road, University of California, Merced, CA 95343. Phone: 209-228-2429, Email: [email protected] RELATIONAL EMPATHY 2 Abstract Empathy is an extensively studied construct, but operationalization of effective empathy is routinely debated in popular culture, theory, and empirical research. This paper offers a process-focused approach emphasizing the relational functions of empathy in interpersonal contexts. We argue that this perspective offers advantages over more traditional conceptualizations that focus on primarily intrapsychic features (i.e., within the individual). Our aim is to enrich current conceptualizations and empirical approaches to the study of empathy by drawing on psychological, philosophical, medical, linguistic, and anthropological perspectives. In doing so, we highlight the various functions of empathy in social interaction, underscore some underemphasized components in empirical studies of empathy, and make recommendations for future research on this important area in the study of emotion. -

Back Pain and Emotional Distress

Back Pain and Emotional Distress North American Spine Society Public Education Series Common Reactions to Back Pain Four out of five adults will experience an episode of significant back pain sometime during their life. Not surprisingly, back pain is one of the problems most often seen by health care providers. Fortunately, the majority of patients with back pain will successfully recover and return to normal social and work activities within 2-4 months, often without treatment. In 1979, the major professional organization specializing in pain—the International Association for the Study of Pain—introduced the most widely used definition of pain: “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential damage, or described in terms of such damage.” This pain is a complex experience that includes both physical and psychological factors. It is quite normal to have emotional reactions to acute back pain. These reactions can include fear, anxiety and worry about what the pain means, how long it will last and how much it will interfere with activities of daily living. Though it’s normal to avoid activity that causes pain, complete inactivity is ill-advised. Rather, it is important to take an active role in managing pain by participating in physician-guided activities. There are now accepted clinical guidelines for management of acute back pain (by definition, within the first 10 weeks of pain) and its associated stress. These guidelines emphasize: Addressing patients’ fears and misconceptions about back pain Providing a reasonable explanation for the pain as well as an expected outcome Empowering the patient to resume/restore normal activities of daily living through simple prescribed exercises and graded activity. -

Opioids for Acute Pain What You Need to Know

Opioids for Acute Pain What You Need to Know Types of Pain Acute pain usually occurs suddenly and has a known cause, like an injury, surgery, or infection. You may have experienced acute pain, for example, from a wisdom tooth extraction, an outpatient medical procedure, or a broken arm after a car crash. Acute pain normally resolves as your body heals. Chronic pain, on the other hand, can last weeks or months—past the normal time of healing. Prescription Opioids Prescription opioids (like hydrocodone, oxycodone, and morphine) are one of the many options for treating severe Nonopioid options include: acute pain. While these medications can reduce pain during short-term use, they come with serious risks including Pain relievers like addiction and death from overdose when taken for longer ibuprofen, naproxen, periods of time or at high doses. and acetaminophen Acute pain can be managed without opioids Acupuncture or massage Ask your doctor about ways to relieve your pain that do not involve prescription opioids. These treatments may actually work better and have fewer risks and side effects. Application of heat or ice Ask your doctor about your options and what level of pain relief and improvement you can expect for your acute pain. Learn More: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose Opioids for Acute Pain: What You Need to Know If You Are Prescribed Opioids Know your risks It is critical to understand the potential side effects and risks of opioid pain medications. Even when taken as directed, opioids can have several side effects including: · Tolerance, meaning you might need to take more of · Physical dependence, meaning you have withdrawal a medication for the same pain relief symptoms when a medication is stopped—this can · Constipation develop within a few days · Nausea and vomiting · Confusion · Dry mouth · Depression · Sleepiness and dizziness · Itching Know what to expect from your doctor If your doctor is prescribing opioids for acute pain, you can expect him or her to protect your safety in some of the following ways.