"Red" Faber (Chicago AL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of University Of

UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON MEDIA ALMANAC 2012 COUGAR BASEBALL WWW.UHCOUGARS.COM UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON MEDIA ALMANAC 2012 COUGAR BASEBALL WWW.UHCOUGARS.COM 2012 HOUSTON BASEBALL CREDITS Executive Editor Jamie Zarda Kailee Neumann Allison McClain Editors Dave Reiter, Jeff Conrad Editorial Assistance Mike McGrory Layout Jamie Zarda, Allison McClain Printing University of Houston Printing and Postal Services UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS 3100 Cullen Blvd. Houston, Texas 77204-6002 www.UHCougars.com MEDIA ALMANAC INTRODUCTION Career Leaders 68-69 GENERAL INFORMATION Table of Contents 3 Single-Season Leaders 70-71 Location Houston, Texas Media Information 4 Team Single-Season Leaders 72-73 Enrollment 39,800 Roster 5 Year-by-Year Leaders 74-76 Founded 1927 INTRODUCTION Schedule 6 Year-by-Year Lineups 77-79 Nickname Cougars Against Ranked Teams 80-81 Colors Scarlet and White COACHING STAFF Year-by-Year Pitching Stats 82 President Dr. Renu Khator Todd Whitting 8 Year-by-Year Hitting Stats 83 Athletics Director Mack Rhoades Trip Couch 9 Standout Hitting Performances 84 Faculty Representative Dr. Richard Scamell Jack Cressend 10 Standout Pitching Performances 85 SWA DeJuena Chizer Ryan Shotzberger/Traci Cauley 11 Attendance Records 86 Conference Conference USA Support Staff 12 Coaching History 87 Began C-USA Competition 1996 All-Time Roster 88-89 2012 COUGARS All-Time Jersey Numbers 90-91 BASEBALL STAFF Season Preview 14 The Last Time... 92 Head Coach Todd Whitting Cannon/Lewis 15 Retired Jersey 93 Alma Mater, Year Houston, 1995 Morehouse -

The Meadoword, June 2017

June 2017 Volume 35, Number 06 The To FREE Meadoword MeaThe doword PUBLISHED BY THE MEADOWS COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION TO PROVIDE INFORMATION AND EDUCATION FOR MEADOWS RESIDENTS MANASOTA, FL MANASOTA, U.S. POSTAGE PRESORTED STANDARD PERMIT 61 PAID PDF done -CC 2 The Meadoword • June 2017 MCA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Notes From the Claire Coyle, President Marilyn Maleckas, Vice President Joe Miller, Treasurer Malcolm Hay, Secretary President’s Desk Bob Clark Claire Coyle—MCA President Bruce Ferretti Phil Hughes Jan Lazar The Renaissance of property values will increase by more distributed about a year ago. Leaders Dr. Bart Levenson The Meadows than six percent. And, that is only the of the community built on this data in COMMITTEES beginning. two meetings of association presidents Assembly of Property Owners is about to begin Real estate experts tell us that new and assembly members. The result is a Pam Campbell, Chair plan that calls for upgrading the overall Claire Coyle, Liaison construction usually causes the value The recent announcement that The look of our community. Communications of properties in the surrounding areas Claire Coyle, Chair Meadows Country Club has signed an to increase Everything ties together to make Community Involvement agreement with a developer to build this time an incredibly exciting one Marilyn Maleckas, Chair up to 180 new units on the property New construction also stimulates to be a member of The Meadows Finance and Budget now owned by the country club existing homeowners to invest in community. New building will bring Jerry Schwarzkopf, Chair signaled the start of the revitalization upgrading their properties to keep new people and renewed energy. -

PDF of August 17 Results

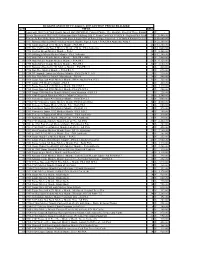

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Baseball Cyclopedia

' Class J^V gG3 Book . L 3 - CoKyiigtit]^?-LLO ^ CORfRIGHT DEPOSIT. The Baseball Cyclopedia By ERNEST J. LANIGAN Price 75c. PUBLISHED BY THE BASEBALL MAGAZINE COMPANY 70 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY BALL PLAYER ART POSTERS FREE WITH A 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION TO BASEBALL MAGAZINE Handsome Posters in Sepia Brown on Coated Stock P 1% Pp Any 6 Posters with one Yearly Subscription at r KtlL $2.00 (Canada $2.00, Foreign $2.50) if order is sent DiRECT TO OUR OFFICE Group Posters 1921 ''GIANTS," 1921 ''YANKEES" and 1921 PITTSBURGH "PIRATES" 1320 CLEVELAND ''INDIANS'' 1920 BROOKLYN TEAM 1919 CINCINNATI ''REDS" AND "WHITE SOX'' 1917 WHITE SOX—GIANTS 1916 RED SOX—BROOKLYN—PHILLIES 1915 BRAVES-ST. LOUIS (N) CUBS-CINCINNATI—YANKEES- DETROIT—CLEVELAND—ST. LOUIS (A)—CHI. FEDS. INDIVIDUAL POSTERS of the following—25c Each, 6 for 50c, or 12 for $1.00 ALEXANDER CDVELESKIE HERZOG MARANVILLE ROBERTSON SPEAKER BAGBY CRAWFORD HOOPER MARQUARD ROUSH TYLER BAKER DAUBERT HORNSBY MAHY RUCKER VAUGHN BANCROFT DOUGLAS HOYT MAYS RUDOLPH VEACH BARRY DOYLE JAMES McGRAW RUETHER WAGNER BENDER ELLER JENNINGS MgINNIS RUSSILL WAMBSGANSS BURNS EVERS JOHNSON McNALLY RUTH WARD BUSH FABER JONES BOB MEUSEL SCHALK WHEAT CAREY FLETCHER KAUFF "IRISH" MEUSEL SCHAN6 ROSS YOUNG CHANCE FRISCH KELLY MEYERS SCHMIDT CHENEY GARDNER KERR MORAN SCHUPP COBB GOWDY LAJOIE "HY" MYERS SISLER COLLINS GRIMES LEWIS NEHF ELMER SMITH CONNOLLY GROH MACK S. O'NEILL "SHERRY" SMITH COOPER HEILMANN MAILS PLANK SNYDER COUPON BASEBALL MAGAZINE CO., 70 Fifth Ave., New York Gentlemen:—Enclosed is $2.00 (Canadian $2.00, Foreign $2.50) for 1 year's subscription to the BASEBALL MAGAZINE. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Hemingway Gambles and Loses on 1919 World Series

BLACK SOX SCANDAL Vol. 12, No. 1, June 2020 Research Committee Newsletter Leading off ... What’s in this issue ◆ Pandemic baseball in 1919: Flu mask baseball game... PAGE 1 ◆ New podcast from Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum ........ PAGE 2 ◆ Alias Chick Arnold: Gandil’s wild west early days ..... PAGE 3 ◆ New ESPN documentary shines light on committee work .. PAGE 11 ◆ Hemingway gambles, loses on 1919 World Series ...... PAGE 12 ◆ Photos surface of Abe Attell’s World Series roommate . PAGE 14 ◆ Shano Collins’ long-lost interview with the Boston Post ..... PAGE 15 ◆ George Gorman, lead prosecutor in the Black Sox trial . PAGE 20 ◆ What would it take to fix the 2019 World Series? ..... PAGE 25 John “Beans” Reardon, left, wearing a flu mask underneath his umpire’s mask, ◆ John Heydler takes a trip prepares to call a pitch in a California Winter League game on January 26, 1919, in to Cooperstown ........ PAGE 28 Pasadena, California. During a global influenza pandemic, all players and fans were required by city ordinance to wear facial coverings at all times while outdoors. Chick Gandil and Fred McMullin of the Chicago White Sox were two of the participants; Chairman’s Corner Gandil had the game-winning hit in the 11th inning. (Photo: Author’s collection) By Jacob Pomrenke [email protected] Pandemic baseball in 1919: At its best, the study of histo- ry is not just a recitation of past events. Our shared history can California flu mask game provide important context to help By Jacob Pomrenke of the human desire to carry us better understand ourselves, [email protected] on in the face of horrific trag- by explaining why things hap- edy and of baseball’s place in pened the way they did and how A batter, catcher, and American culture. -

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library Guide to the Sporting Life Cabinet Card Collection, 1902-1906

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library Guide to the Sporting Life Cabinet Card Collection, 1902-1906 Descriptive Summary Repository: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Creator: Sporting Life Publishing Company (Philadelphia, Pa.) Title: Sporting Life Cabinet Card Collection (W600) Language: English Location: Photo Archive Abstract: Collection of baseball cards issued as premiums by the Sporting Life Publishing Company of Philadelphia from 1902 to 1911. The cards contain bust-length portraits of professional baseball players, dressed in uniform and street clothes, who were active during the issuing period. The set is comprised entirely of monochromatic, photomechanical prints mounted on cardboard measuring 5 x 7 1/2 inches. Extent: 281 items in 2 boxes Access: Available by appointment, Monday-Friday 9AM to 4 PM. Copyright: Individual researchers are responsible for using these materials in accordance with both copyright law and any donor restrictions accompanying the materials. Preferred Citation: Sporting Life Cabinet Card Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY Acquisitions Information: The collection was given to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by two donors, William A. Merritt of Lowell, Massachusetts in 1952 and Peter Stebbins Craig in 1969. Processing Information: Described by Carlos Pearman, Photo Archive intern, July 2009. Additions and editing by Jenny Ambrose, Assistant Photo Archivist. Biographical Sketch Founded by former baseball player and famed sportswriter Francis C. Richter, the Sporting Life Publishing Company of Philadelphia published Sporting Life, a weekly newspaper devoted to “base ball, trap shooting and general sports” from 1883 to 1917, and from 1922 to 1924. Richter also edited the Reach baseball guides from their inception in 1901 until his death in 1926. -

Standings Compiled by Secretary the Third Out

1 ■— — « —— ■ ■■ ■ —— been torn out, and a new aidawalk 3 WALKS PLUS 3 is being put in. < Cardinals Headed Toward * * * Both these store spares are also Pennant; Pitching TUNNEY NEARS being remodeled, and the Broad- EDINBURG ON Men's way Shop, owned by Ben HITS ONE was And Best In Avers Vessels EQUAL Epstein, and which damaged by Batting League * *. * fire several weeks ago, is to be re- opened soon. Lf FLAYING TOP IN UPPER RUN —PROF. HUG TRAINING END _ 17.—(A*—The Edcouch Go NEW YORK. July McAllen, Cleveland Indians have demon- Champ to Box and Eat Up As Donna and strated how a team can make three safe hits and receive three bases Great Quantities I _ Pharr Lose on balls in one inning and still Of Meat Out of score only one run. \ankees Snap this bracket— The Indians performed Upper feat for the benefit of SPECULATOR. N. Y. July 17.— Slump Taking Two; Team W. L. Prt. strange metropolian fans watching them a rest from all Edinburg 9 3 .750 (/Fb—After 24-hour lose both ends if a double-header Cards Emerge After McAllen 7 5 .583 ring work. Gene Tunney decided to to the New York Yankees yester- Donna 7 6 .538 renew exchanging blows with his Losing Pair Edcouch 5 7 .417 day. sparring partners today to fit him- In the third of the first Pharr 2 11 .153 inning self for his world's heavyweight title Lind to right and BY HERBERT W. BARKER Lower bracket— game, singled bout against Tom Hceney on July 26. -

Baseball All-Time Stars Rosters

BASEBALL ALL-TIME STARS ROSTERS (Boston-Milwaukee) ATLANTA Year Avg. HR CHICAGO Year Avg. HR CINCINNATI Year Avg. HR Hank Aaron 1959 .355 39 Ernie Banks 1958 .313 47 Ed Bailey 1956 .300 28 Joe Adcock 1956 .291 38 Phil Cavarretta 1945 .355 6 Johnny Bench 1970 .293 45 Felipe Alou 1966 .327 31 Kiki Cuyler 1930 .355 13 Dave Concepcion 1978 .301 6 Dave Bancroft 1925 .319 2 Jody Davis 1983 .271 24 Eric Davis 1987 .293 37 Wally Berger 1930 .310 38 Frank Demaree 1936 .350 16 Adam Dunn 2004 .266 46 Jeff Blauser 1997 .308 17 Shawon Dunston 1995 .296 14 George Foster 1977 .320 52 Rico Carty 1970 .366 25 Johnny Evers 1912 .341 1 Ken Griffey, Sr. 1976 .336 6 Hugh Duffy 1894 .440 18 Mark Grace 1995 .326 16 Ted Kluszewski 1954 .326 49 Darrell Evans 1973 .281 41 Gabby Hartnett 1930 .339 37 Barry Larkin 1996 .298 33 Rafael Furcal 2003 .292 15 Billy Herman 1936 .334 5 Ernie Lombardi 1938 .342 19 Ralph Garr 1974 .353 11 Johnny Kling 1903 .297 3 Lee May 1969 .278 38 Andruw Jones 2005 .263 51 Derrek Lee 2005 .335 46 Frank McCormick 1939 .332 18 Chipper Jones 1999 .319 45 Aramis Ramirez 2004 .318 36 Joe Morgan 1976 .320 27 Javier Lopez 2003 .328 43 Ryne Sandberg 1990 .306 40 Tony Perez 1970 .317 40 Eddie Mathews 1959 .306 46 Ron Santo 1964 .313 30 Brandon Phillips 2007 .288 30 Brian McCann 2006 .333 24 Hank Sauer 1954 .288 41 Vada Pinson 1963 .313 22 Fred McGriff 1994 .318 34 Sammy Sosa 2001 .328 64 Frank Robinson 1962 .342 39 Felix Millan 1970 .310 2 Riggs Stephenson 1929 .362 17 Pete Rose 1969 .348 16 Dale Murphy 1987 .295 44 Billy Williams 1970 .322 42 -

Baseball Cards Have New T3s, T202 Triple Folders, B18 Blankets, 1921 E121s, 1923 Willard’S Chocolates and 1927 W560s

Clean Sweep: The Sweet Spot for Auctions The sports memorabilia business seems to have an auction literally every day, not to mention ebay. Some auctions are telephone book size catalogs with multiple examples of the same item (thus negatively affecting prices) while others are internet-only auctions that run for a short time and have only been in business for a relatively short time (5 years or less). Clean Sweep Auctions is the sweet spot of sports auction companies. We have been in business for over 20 years and have one of the deepest and best mailing lists of any auction house. Do not think for a second that a printed catalog in addition to a full fledged website will not result in higher prices for your prized collection. Clean Sweep has extensive, virtually unmatched experience in working with all higher quality vintage cards, autographs and memorabilia from all of the major sports. Our catalogs are noted for their extremely accurate descriptions, great pictures and easy to read layout, including a table of contents. Our battle tested website is the best in the business, combining great functionality with ease of use. Clean Sweep will not put your cherished collection in random or overly large lots, killing the potential to get a top price. We can spread out your collection over different types of auctions, maximizing prices. We work harder and smarter than anyone in the business to bring top dollar for your collection at auction. Clean Sweep is extremely well capitalized, with large interest-free cash advances available at any time. -

Konerko: Mr. White Sox for the New Millennium

Konerko: Mr. White Sox for the new millennium By Dr. David J. Fletcher, CBM President Posted Monday, September 30th, 2013 Although it was a disaster for both the Cubs and Sox, the end of Chicago baseball season is always sad. The transition to October is a sorrowful moment even this year. Both teams finished in last place with a combined record of 129- 195. That mark sets all-time Chicago baseball record for futility with the most combined losses. This season is a far cry from 2008, when both teams advanced to Paul Konerko talks the postseason together for the first time since the 1906 World about possible re- Series. The first-ever Subway Series finally was a possibility. But tirement in his dug- both the Cubs and Sox quickly fizzled in the Division Series. Nei- out press conference ther has made the postseason since. on Sept. 27. For me as a Chicago baseball historian, the hardest thing about the season end is the fact that Sunday’s curtain-closer at U.S. Cellular Field might have been be the final time that Paul Konerko (“PK”) appeared in a Sox uniform. PK was pulled from the game, walking off from his first-base position, in a class move by Manager Robin Ventura. He left after one out in the 2nd inning to allow the Chicago faithful one more time to cheer for PK to shouts of “Paulie…Paulie…Paulie.” As is his custom, PK did not soak up the limelight and exited his as fast as possible to get to the dugout, acknowledging the fans with a brief curtain call and hugs/high fives from his teammates in the dugout. -

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014 A complete record of my full-season Replays of the 1908, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1966, 1967, 1975, and 1978 Major League seasons as well as the 1923 Negro National League season. This encyclopedia includes the following sections: • A list of no-hitters • A season-by season recap in the format of the Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia- Baseball • Top ten single season performances in batting and pitching categories • Career top ten performances in batting and pitching categories • Complete career records for all batters • Complete career records for all pitchers Table of Contents Page 3 Introduction 4 No-hitter List 5 Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia Baseball style season recaps 91 Single season record batting and pitching top tens 93 Career batting and pitching top tens 95 Batter Register 277 Pitcher Register Introduction My baseball board gaming history is a fairly typical one. I lusted after the various sports games advertised in the magazines until my mom finally relented and bought Strat-O-Matic Football for me in 1972. I got SOM’s baseball game a year later and I was hooked. I would get the new card set each year and attempt to play the in-progress season by moving the traded players around and turning ‘nameless player cards” into that year’s key rookies. I switched to APBA in the late ‘70’s because they started releasing some complete old season sets and the idea of playing with those really caught my fancy. Between then and the mid-nineties, I collected a lot of card sets.