American Excess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1920 Patricia Ann Mather AB, University

THE THEATRICAL HISTORY OF WICHITA, KANSAS ' I 1872 - 1920 by Patricia Ann Mather A.B., University __of Wichita, 1945 Submitted to the Department of Speech and Drama and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Redacted Signature Instructor in charf;& Redacted Signature Sept ember, 19 50 'For tne department PREFACE In the following thesis the author has attempted to give a general,. and when deemed.essential, a specific picture of the theatre in early day Wichita. By "theatre" is meant a.11 that passed for stage entertainment in the halls and shm1 houses in the city• s infancy, principally during the 70' s and 80 1 s when the city was still very young,: up to the hey-day of the legitimate theatre which reached. its peak in the 90' s and the first ~ decade of the new century. The author has not only tried to give an over- all picture of the theatre in early day Wichita, but has attempted to show that the plays presented in the theatres of Wichita were representative of the plays and stage performances throughout the country. The years included in the research were from 1872 to 1920. There were several factors which governed the choice of these dates. First, in 1872 the city was incorporated, and in that year the first edition of the Wichita Eagle was printed. Second, after 1920 a great change began taking place in the-theatre. There were various reasons for this change. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Midwestern Gilbert and Sullivan Society

NEWSLETTER OF THE MIDWESTERN GILBERT AND SULLIVAN SOCIETY September 1990 -- Issue 27 But the night has been long, Ditto, Ditto my song, And thank goodness they're both of 'em over! It isn't so much that the night was long, but that the Summer was (or wasn't, as the case may be). This was not one of S/A Cole's better seasons: in June, her family moved to Central Illinois; in July, the computer had a head crash that took until August to fix, and in that month, she was tired and sick from all the summer excitement. But, tush, I am puling. Now that Autumn is nearly here, things are getting back to normal (such as that is). Since there was no summer Nonsense, there is all kinds of stuff in this issue, including the answers to the Big Quiz, an extended "Where Can it Be?/The G&S Shopper", reports on the Sullivan Festival and MGS Annual Outing, and an analysis of Thomas Stone's The Savoyards' Patience. Let's see what's new. First of all, we owe the Savoy-Aires an apology. Oh, Members, How Say You, S/A Cole had sincerely believed that an issue of the What is it You've Done? Nonsense would be out in time to promote their summer production of Yeomen. As we know now, Member David Michaels appeared as the "First no Nonsense came out, and the May one didn't even Yeomen" in the Savoy-Aires' recent production of mention their address. Well, we're going to start to The Yeomen of the Guard. -

Pringle Papers - Theatre Programs - Grand Opera House Not Dated Recital by Marie Hall 1421

Pringle Papers - Theatre Programs - Grand Opera House not dated Recital by Marie Hall 1421 Prospectus. Franz Molnar's 1422- 1431 “The devil" The following programs are not all Grand Opera house programs, but as they are fastened together probably by Mrs. Pringle herself, and contain the bill for the opening night of the house they, have been included in this unit. 1880 Sept.30 XIIIth battalion band 1432 The incomparable Lotta. incomplete 1433 Mendelssohn quartette club of Boston with Marie Nellini 1434 - 1440 A.Farini English opera co 1441 Fisk university jubilee singers with notes 1442 - 1445 Nov.9 Opening night of the Grand opera house. Salsbury's troubadours 1446 -- Corinne merrymakers. incomplete 1447 -- Boston ideal opera company in -- "Fatinitza: and "The Bells of Corneville" 1448 - 1449 -- Rive-King concerts 1450 1880 Dec.22 concert at "Merksworth" 1451 Dec.27 Christ's church cathedral concert 1452 Dec.31 "Opera mad" 1453 - 1457 -- Emma Abbott in "Paul and Virginia1458 1881 Jan.22 Hi Henry's minstrels 1459 - 1462 Feb.9 Garrick club presenting W.S. Gilbert's comedy "Sweethearts" 1463 - 1466 J. Moodie and sons illus 1466 End of papers fastened together. 1880 Mar.2 MUSIN grand concert company 1467 - 1468 1882 Mar.14 The Al. G. Field ministrels 1469 - 1472-a 1885 May 28 Hamilton musical union. Concert for volunteer in the Northwest 1472-b - 1472-e Sept.7 Lotta and her comedy company 1472-f 1888 Nov.8 Boston ideal opera co. in "Daughter of the regiment" 1473 - 1476 Nov.23 "Billee taylor" with local cast 1477 - 1479 Dec.7 J.C.Duff comic opera co. -

Lillian Russell

T OUR i l l i a n u s s e l l L R Historic Allegheny Cemetery the “Beautiful English Ballad Singer” To Visit Famous Gravesites and Star of Stage and Screen Stephen C. Foster “Rosey” Rowswell Josh Gibson Harry Kendall Thaw Charles Avery General John Neville General James O’Hara Commodore Joshua Barney and More of Pittsburgh’s History A Legend From Pittsburgh Allegheny Cemetery Historical Association 4734 Butler Street Private Mausoleum Pittsburgh PA 15201-2999 Section 40 Lot 5 412/682-1624 FAX 412/622-0655 www. Alleghenycemetery.com ALLEGHENY CEMETERY PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA illian Russell was born Helen Louise Leonard in Clinton, illian Russell was an American light-opera soprano, known for her L Iowa on December 4, 1861. She died June 6, 1922 (60 years L beauty and flamboyant life-style as well as for her singing ability. old) from cardiac exhaustion at 6744 Penn Avenue, Pittsburgh, She studied in Chicago and first appeared on stage in 1879 in New York City in the chorus of “H.M.S. Pinafore” by the British playwright- Pennsylvania and was interred June 8, 1922 in this Private Mauso- composer team of Gilbert and Sullivan. She sang in various opera leum in Allegheny Cemetery. companies in England and the United States including one that she headed (Lillian Russell Opera Company) and from 1899 to 1904 with the noted We assume that her husband, who was the publisher of the Pitts- Weber and Fields company of New York. Her most famous roles burgh Leader newspaper, Alexander Penn Moore, requested that included leading parts in the operettas of Gilbert and Sullivan and those of the quote below be inscribed on the Mausoleum since Lillian pre- Jacques Offenbach. -

Untitled, It Is Impossible to Know

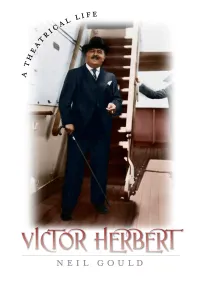

VICTOR HERBERT ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE i ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE ii VICTOR HERBERT A Theatrical Life C:>A<DJA9 C:>A<DJA9 ;DG9=6BJC>K:GH>INEG:HH New York ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2008 Neil Gould All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Neil, 1943– Victor Herbert : a theatrical life / Neil Gould.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2871-3 (cloth) 1. Herbert, Victor, 1859–1924. 2. Composers—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML410.H52G68 2008 780.92—dc22 [B] 2008003059 Printed in the United States of America First edition Quotation from H. L. Mencken reprinted by permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, Maryland, in accordance with the terms of Mr. Mencken’s bequest. Quotations from ‘‘Yesterthoughts,’’ the reminiscences of Frederick Stahlberg, by kind permission of the Trustees of Yale University. Quotations from Victor Herbert—Lee and J.J. Shubert correspondence, courtesy of Shubert Archive, N.Y. ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iv ‘‘Crazy’’ John Baldwin, Teacher, Mentor, Friend Herbert P. Jacoby, Esq., Almus pater ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE v ................ -

The History of the Great Southern Theater, Columbus, Ohio

THE HISTORY OF THE GREAT SOUTHERN THEATER, COLUMBUS, OHIO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By MARCIA A. SIENA, B.A. The Ohio State University 1957 Approved by: Speech TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION, REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE, AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND • • • • • 1 Introduction • 1 Review of the Literature . 1 Historical Background • • 3 II. THE GREAT SOUTHERN THEATER • • • • 8 The Financial Backing 8 The Physical Plant . • • 8 LObby, foyer, and promenade balcony • • 9 Auditorium • • 11 Stage Area • • • • 16 Changes . • • 28 III. PRODUCTION IN THE GREAT SOUTHERN THEATER • 37 Scenery • 39 Lighting . • • 42 Special Effects • • 51 Traps . • 51 Treadmills • 54 Flying • 54 Others 56 IV. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS • • • 57 Summary • • • 57 Conclusions • 58 ii PAGE APPENDIX • • 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY • 100 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE PAGE 1. The Great Southern Hotel and Theater, 1896 • • 10 2. Original Interior Design • 12 3. Orchestra Seating Chart • 14 4. Balcony and Gallery Seating Chart 15 5. Proscenium Arch and Stage 17 6. Proscenium Arch • • 18 7. Light Board • • • • • 20 8. Pin Rail • 21 9. Paint Frame and Workbench • 22 10. Grid and Pulley Bank • • 24 11. Bull Wheel • • • 25 12. Tunnel • 26 13. Elevators • 27 14. Top of Elevators • • 29 15. Great Southern Theater, 1914 • • 31 16. Great Southern Theater, 1957 • • 32 17. Foyer • 33 18. Gallery • • 34 19. Sketch of Auditorium, 1896 • 35 20. Auditorium, 1957 • 36 21. Under The ~ ~ Act III • • • 43 22. Under The Red ~ Act III, Scene II • 44 23. The Devil's Disciple Act IV • 45 iv FIGURE PAGE 24. -

Transcribed Pages from the Charles Dickson Papers

Transcribed Pages from the Charles Dickson Papers Box 3 Binder 6: Mobile Theaters, vol. 6 1. Mob Register, Jan. 31, 1895 Captain Hooper Early Musicians in Mobile “The first musician of whom I have an early recollection was a man by the name of Kuhn, a piano tuner by occupation,” states the writer for the “Diamond Wedding Edition.” “He played fairly well on the piano.” He played on the organ in the Cathedral, the organ now in St. John’s Episcopal Church. This organ is or was before it was altered one of the oldest in this country. It was purchased in Germany and imported by Bishop Portier. It had two banks of keys about fifteen stops, and no swell. In the days when this organ was originally built, such a thing as a swell was unknown. There was a man by the name of Hooper who sang bass in the Cathedral about the time Mr. Kuhn was organist. “He was from Boston, I think.” He subsequently became captain of the Washington Light Infantry. He was passionatly fond of music and a zealous member of the Musical Association. “I think he returned to his northern home and died. “Another musician who flourished was a Professor Fuertes, a Spaniard or Cuban” organist at the Government Street Presbyterian Church. About the time Fuertes left here, there came a German: Dr. Lingen. He came from Philadelphia. He was too poor when he first came here to drive about in a buggy, and had to make his professional calls. He was a homeopathic doctor and, it was said, he combined for a livelihood physic in the day and music at night, playing the cello in the Theatre Orchestra, etc. -

A Survey of Professional Operatic Entertainment in Little Rock, Arkansas: 1870-1900 Jenna M

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 A survey of professional operatic entertainment in Little Rock, Arkansas: 1870-1900 Jenna M. Tucker Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Tucker, Jenna M., "A survey of professional operatic entertainment in Little Rock, Arkansas: 1870-1900" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SURVEY OF PROFESSIONAL OPERATIC ENTERTAINMENT IN LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS: 1870-1900 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In The School of Music by Jenna Tucker B.M., Ouachita Baptist University, 2002 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2004 May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I praise God for the grace and mercy that He has shown me throughout this project. Also, I am forever grateful to my major professor, Patricia O‟Neill, for her wisdom and encouragement. I am thankful to the other members of my committee: Dr. Loraine Sims, Dr. Lori Bade, Professor Robert Grayson, and Dr. Edward Song, for their willingness to serve on my committee as well as for their support. -

9780521871808 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87180-8 — Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture Laurence Senelick Index More Information 332 Index À l’ombre des jeunes i lles en l eur , novel (M. Anderson, Percy 120 Proust, 1918)) 85 Angélo, tyran de Padoue, play (V. Hugo, 1835) 41 Abel- Helena , parody (A. de Azevedo, 1873) 184 Anna Karenina , novel (L. N. Tolstoy, 1875– 77) Abendroth, Walter 216 151 , 159 Aborn Opera Company 252 Anouilh, Jean 247 Academy of Music, Montreal 122 anti- semitism 96 , 300 – 301 Academy of Music, New York 132 in France 68 , 235 – 36 , 238 – 39 Achard, Marcel 244 – 45 in Germany 73 , 77 – 78 , 215 – 19 , 271 Action Française 239 Wagner’s 67 – 71 , 198 Adam, Adolphe 30 Antony , play (A. Dumas père , 1831) 19 Adams, A. Davies 256 Arcadians, h e , musical comedy ((R. Adelphi h eatre, London 101 , 120 , 259 – 60 Courtneidge, A. M. h ompson and M. Adler, Hans Günther 218 Ambruin, music L. Monckton and H. Admiralspalast, Berlin 273 Talbot, 1909) 120 Adorno, h eodor W. 5 – 6 , 201 , 214 Archer, William 116 , 118 Adventures of Robin Hood, h e , i lm (M. Curtiz Arderíus, Francisco 172 – 74 , 180 and W. Keighley, 1938) 261 Argus , Melbourne, periodical 190 Æneid , epic poem (Vergil) 18 Ariadne auf Naxos , opera (R. Strauss, 1912) 202 Agoult, Marie, comtesse d’ (Daniel Stern) 73 Ariane et Barbe- bleue , opera (P. Dukas, 1907) 281 Aïda , opera (G. Verdi, 1871) 185 Aristophanes 112 , 264 , 267 Aimée, Marie 133 , 136 – 37 , 180 , 183 Arlequin barbier , pantomime (J. Of enbach Aimée Opera Company 128 from G. -

BACKTRACK MUSICALS – Lpsjuly 2021

BACKTRACK MUSICALS – LPs Sept. 2021 The Old Grammar School, High Street, Rye, E. Sussex, TN31 7JF Tel: 01797 222777 website: www.backtrackrye.com e-mail: [email protected] GUARANTEE: All items in this catalogue are guaranteed. If you are not completely happy with your purchase, we will refund your money. All items are new and unplayed Stereo recordings unless otherwise stated. Second-Hand items are only listed if in Mint or Excellent condition. POSTAGE & PACKING: Free to U.K. customers. Overseas orders will be charged at actual cost plus £1 per order to cover handling charges - please write, fax or e-mail for details. QUANTITY DISCOUNTS: All orders over £50 qualify for 10% discount; orders over £100 -15%, over £200 -20% and over £350 -25% off. (Single items listed at £50 or more will not qualify for discount, unless part of a larger order) ALTERNATIVES: As some items are in short supply, if possible please list alternative choices. Items may be reserved by telephone before sending payment. ABBREVIATIONS OF COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN: A = Australia; B = Belgium; C = Canada; DK = Denmark; E = England; F = France; G = Germany; GK = Greece; H = Holland; I = Italy; J = Japan; S = Spain; SA - South Africa; US = USA. EC, EEC or EU = European Community. GENERAL ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE CATALOGUE: F/O = Fold Out (Gatefold) Sleeve; S/H = Second-Hand (Used); w. = with. CDs/LPs WANTED: Mint condition used items are always wanted. Please send your list of items for disposal and you will receive Cash/Part Exchange quotes by return. We also welcome “wants” lists and will try to find rarer items at reasonable prices. -

Legendary Ladies Undercover Assignments in Places Like Roosevelt Which Appears on Every Dime

Mills, Pennsylvania. As a reporter for the known work, although not often attrib- move from Scotland to Pittsburgh where and at the Carnegie Internationals. Mary Pittsburgh. The Company, a vital cultural enduring words were her sketches of Museum, Car and Carriage Museum, Pittsburgh area, recognizing famous of the Junior Leagues of America. Kathryn was a divorcee and openly Pittsburgh Dispatch, she took on risky uted to her, is the portrait of Franklin D. they had relatives. After making a for- was a fierce advocate for education and force for 20 years, performed European middle-class life in idyllic, small-town Visitors’ Center and Museum Shop, MARTHA GRAHAM people, places, and events. A tablet in Mrs. Harry Darlington, Jr. was the enjoyed the expensive lifestyle her legendary ladies undercover assignments in places like Roosevelt which appears on every dime. tune in steel, Andrew founded the women’s rights. Seventeen of Mary’s works, such as Verdi’s Aida and La Traviata, “Old Chester,” and the adventures of Greenhouse, and The Café at the Frick. memory of Julia Hogg was dedicated on first president. Early efforts focused ministry afforded her. Nevertheless, sweatshops, slums, and jails. It was She was named a Distinguished Daughter Carnegie Institute of Technology (now works are part of the Carnegie Museum and African-American works, such as country parson Dr. Lavendar. Margaret It is Helen’s legacy to her hometown. June 10, 1941, on the 50th anniversary on volunteer work in hospitals, she was wildly popular, ministering George Madden, the managing editor of of Pennsylvania in 1993. Carnegie Mellon University), and the of Art’s permanent collection.