Historical Society Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Legal History

WESTERN LEGAL HISTORY THE JOURNAL OF THE NINTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT HISTORiCAL SOCIETY VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 SUMMER/FALL 1988 Western Legal History is published semi-annually, in spring and fall, by the Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society, P.O. Box 2558, Pasadena, California 91102-2558, (818) 405-7059. The journal explores, analyzes, and presents the history of law, the legal profession, and the courts - particularly the federal courts - in Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Western Legal History is sent to members of the Society as well as members of affiliated legal historical societies in the Ninth Circuit. Membership is open to all. Membership dues (individuals and institutions): Patron, $1,000 or more; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499; Sustaining, $100-$249; Advocate, $50-$99; Subscribing (non- members of the bench and bar, attorneys in practice fewer than five years, libraries, and academic institutions), $25-$49. Membership dues (law firms and corporations): Founder, $3,000 or more; Patron, $1,000-$2,999; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499. For information regarding membership, back issues of Western Legal History, and other Society publications and programs, please write or telephone. POSTMASTER: Please send change of address to: Western Legal History P.O. Box 2558 Pasadena, California 91102-2558. Western Legal History disclaims responsibility for statements made by authors and for accuracy of footnotes. Copyright 1988 by the Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society. ISSN 0896-2189. The Editorial Board welcomes unsolicited manuscripts, books for review, reports on research in progress, and recommendations for the journal. -

Populism and Politics: William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party

University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Politics Political Science 1974 Populism and Politics: William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party Peter H. Argersinger University of Maryland Baltimore County Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Argersinger, Peter H., "Populism and Politics: William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party" (1974). American Politics. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_science_american_politics/8 POPULISM and POLITICS This page intentionally left blank Peter H. Argersinger POPULISM and POLITICS William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party The University Press of Kentucky ISBN: 978-0-8131-5108-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-86400 Copyright © 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University- Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky -

The Spine of American Law: Digital Text Analysis and U.S. Legal Practice

The Spine of American Law: Digital Text Analysis and U.S. Legal Practice Kellen Funk Princeton University [email protected] Lincoln Mullen George Mason University [email protected] At the opening of the first Nevada legislature in 1861, Territorial Governor James W. Nye, a former New York lawyer, instructed the assembly that they would have to forsake their inherited Mormon statutes that were ill adapted to “the mining interests” of the new territory. “Happily for us, a neighboring State whose interests are similar to ours, has established a code of laws” sufficiently attractive to “capital from abroad.” That neighbor was California, and Nye urged that California’s “Practice Code” be enacted in Nevada, as far as it could “be made applicable.”1 Territorial Senator William Morris Stewart, a famed mining lawyer who would lead the U.S. Senate during Reconstruction, followed the instructions perhaps too well. Stewart literally cut and pasted the latest Wood’s Digest of the California Practice Act into the session bill, crossing out state and California and substituting territory and Nevada where necessary. Stewart copied not just California’s procedure code but also its method of codification, for California had in turn borrowed its code by modifying New York’s. Nye wrote back to the assembly in disgust. The bill—of 715 sections—had reached him late the night before the legislative session was to close. Even in the few hours he had to read it, Nye counted “many errors in the enrolling of it, numbering probably more than three hundred.” Some errors were severe. The code overwrote the specific jurisdictional boundaries of Nevada’s Organic Act by copying California’s arrangements. -

One Hundred Years of Federal Mining Safety and Health Research

IC 9520 INFORMATION CIRCULAR/2010 Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Information Circular 9520 One Hundred Years of Federal Mining Safety and Health Research By John A. Breslin, Ph.D. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Pittsburgh Research Laboratory Pittsburgh, PA February 2010 This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. Disclaimer Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites. Ordering Information To receive documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics, contact NIOSH at Telephone: 1–800–CDC–INFO (1–800–232–4636) TTY: 1–888–232–6348 e-mail: [email protected] or visit the NIOSH Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh. For a monthly update on news at NIOSH, subscribe to NIOSH eNews by visiting www.cdc.gov/niosh/eNews. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2010-128 February 2010 SAFER • HEALTHIER • PEOPLE™ ii CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Beginning: 1910-1925 1 2.1 Early Legislation 1 2.2 Early Mine Disasters 2 2.3 The Origins of the USBM and the Organic Act 7 2.3.1 Initial Safety Research 9 2.4 The USBM and Miner Health 10 2.5 The USBM Opens an Experimental Mine near Pittsburgh 12 2.6 Expansion of the USBM Mission 15 2.7 Expansion of the USBM in Pittsburgh 17 2.8 Early Statistics on Mining Fatalities and Production 18 2.9 The USBM and WW I 19 3. -

Legacies of Exclusion, Dehumanization, and Black Resistance in the Rhetoric of the Freedmen’S Bureau

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: RECKONING WITH FREEDOM: LEGACIES OF EXCLUSION, DEHUMANIZATION, AND BLACK RESISTANCE IN THE RHETORIC OF THE FREEDMEN’S BUREAU Jessica H. Lu, Doctor of Philosophy, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Shawn J. Parry-Giles Department of Communication Charged with facilitating the transition of former slaves from bondage to freedom, the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (known colloquially as the Freedmen’s Bureau) played a crucial role in shaping the experiences of black and African Americans in the years following the Civil War. Many historians have explored the agency’s administrative policies and assessed its pragmatic effectiveness within the social, political, and economic milieu of the emancipation era. However, scholars have not adequately grappled with the lasting implications of its arguments and professed efforts to support freedmen. Therefore, this dissertation seeks to analyze and unpack the rhetorical textures of the Bureau’s early discourse and, in particular, its negotiation of freedom as an exclusionary, rather than inclusionary, idea. By closely examining a wealth of archival documents— including letters, memos, circular announcements, receipts, congressional proceedings, and newspaper articles—I interrogate how the Bureau extended antebellum freedom legacies to not merely explain but police the boundaries of American belonging and black inclusion. Ultimately, I contend that arguments by and about the Bureau contributed significantly to the reconstruction of a post-bellum racial order that affirmed the racist underpinnings of the social contract, further contributed to the dehumanization of former slaves, and prompted black people to resist the ongoing assault on their freedom. This project thus provides a compelling case study that underscores how rhetorical analysis can help us better understand the ways in which seemingly progressive ideas can be used to justify exercises of power and domination. -

"7- If-II.. I Signature 01 Certifying Offici"! ,/ Dllte I 5 !:!L:Je;

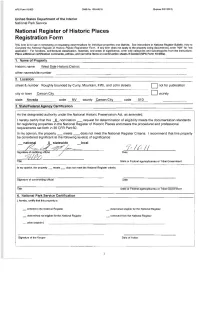

NPS Fom1 11).900 OMB No. 1Q24-OO1B United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ThilJ form is for use in nominating or re<lue&llng detennlnalfons for 'fldividual properties and disbielS. See InstnJctions in National Regisler Buletin, How to Complme the Nationsl R&I}isler of His/orre Places RegistratIOn FomI. 1f any item does oolappty 10 !he propcrty being documented, .enter "N/A" for ·oot appliC8bfe." For functions, afct'liteetural classification, malerials, and areas of SignifICance, enler orty ~legorie$ and 6ubcategories from the tnstnJctlon3. Place additional certification comments, entries, and nan-ative items on continuation sheets it needed (NPS Fonn10·900aj. 1. Name of Property historic name West Side Historic District other names/site number 2. location street & number Roughly bounded by Curry, Mountain, Fifth, and John streets D not for publication city or town ~C"a"r"-so",n-,-"C,,it,-y______________________ _ o vicinity state Nevada code NV county Carson City code 510 3 State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby eMify thai this ....!... nomination _ requesl for delermination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Hisloric Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set fonh in 36 CFR Part 60_ In my opinion, the propeny _ meels __ does not meet the National Regisler Criteria. I recommend that Ihis property be considered significant at the following levet(s) of significance: _na§. J state~l _local ~ ,c: ______ "7- If-II. -

Stewart Vindicated

VOL. 5, NO. 205. NEW YORK, SATURDAY, JANUARY 21, 1905. ONE CENT. EDITORIAL STEWART VINDICATED. By DANIEL DE LEON HO would think that Senator Stewart of Nevada—the old Stewart of “Silver!” “More silver!!” “Still more silver!!!;” that perambulating lump WW of social and economic ignorance, and whose knowledge begins and ends with the low cunning necessary for political wire pulling and for skinning workingmen—who would have thought that he, aye, he would ever contribute a fact that is worth its weight in gold, not silver, to the store of facts upon which Socialist Science is planted? Well, he did; wonderful as it may seem, Stewart did. From the gathered facts Socialism teaches that Labor is plundered of the bulk of its product. A part of the product of Labor is kept by Labor. That part is the part that it needs in order to keep itself alive so as to grind out more wealth for the Capitalist Class, and also in order to reproduce needy proletarians who may succeed it when it has grown old and fit only for the scrapheap. But that part of its own product that Labor keeps is a declining quantity. It declines for two WILLIAM MORRIS STEWART reasons: first, because, Labor being a merchandise (1827–1909) under capitalism, the more there is of it in the Labor market the lower is its price, and privately owned improved machinery steadily dumps a larger supply of Labor on that market; secondly, because Labor is an article whose wants can be squeezed down to almost nothing, provided the squeezing-down process be slow and gradual. -

Journal of Transportation Law, Logistics and Policy

JOURNAL OF TRANSPORTATION LAW, LOGISTICS AND POLICY Vol. 86 2019 No. 1 Board of Directors………………………………………..…… 4 Nominations Committees……………………….…………..… 6 Publications Committee……………………………………..… 6 Editorial Advisory Committee………………………..……….. 7 Association Highlights Contributing Editors………………..… 8 Membership Committee.………………..………………….… 10 Chapter Activities ……………………………………….…… 11 Editorial Policy ..…………………………………….……… 11 Manuscript Submissions…………………………………..…. 12 Permissions Policy Statement……………………………..…. 12 Change of Address……………………………………….….. 12 Student Writing Competition…….……………………..….… 13 Call for Papers …………………………………………….…. 14 Guiding Philosophy of ATLP..…………………………..….… 16 Motor Carriers, Federal Preemption, and the Supreme Court: Back to Basics Mark J. Andrews and Linna T. Loangkote……………….……18 Who Owns the Rights to Railroad Rights-of-Way? Kristine Little…..………………………………………………44 Human Trafficking and Transportation Rebecca Mares……………………………………….…..….…62 Efficiency in Container Allocation in the US and EU: An Institutional Perspective Drew Stapleton and Anup Menon Nandialath..…………..……88 The Journal of Transportation Law, Logistics and Policy (ISSN 1078-5906) is published quarterly by the Association of Transportation Law Professionals, Inc. The subscription price of the Journal to active and retired members ($50) is included in membership dues. Subscription price to non-members (U.S.) is $100; Canada, U.S.$105; Foreign, U.S.$110 (Prepayment required.) Single copy $30, plus shipping and handling. Editorial office and known office of publication: P.O. Box 5407, Annapolis, MD. 21403. Periodicals postage paid at Annapolis, MD. Postmaster: Send address changes to: Journal of Transportation Law, Logistics and Policy, P.O. Box 5407, Annapolis, MD. 21403.Copyright © 2019 by Association for Transportation Law Professionals, Inc.All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. JOURNAL OF TRANSPORTATION LAW, LOGISTICS AND POLICY P.O. Box 5407 Annapolis, MD 21403 (410) 268-1311; FAX (410) 268-1322 [email protected] EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MICHAEL F. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name West Side Historic District other names/site number 2. Location street & number Roughly bounded by Curry, Mountain, Fifth, and John streets not for publication city or town Carson City vicinity state Nevada code NV county Carson City code 510 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national X statewide local ____________________________________ Signature of certifying official Date _____________________________________ Title State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

The Color of Wealth in the Nation's Capital

INEQUALITY AND MOBIL ITY (just RESEARCH REPORT The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital A Joint Publication of the Urban Institute, Duke University, The New School, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development Kilolo Kijakazi Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins Mark Paul Anne E. Price URBAN INSTITUTE THE NEW SCHOOL DUKE UNIVERSITY INSIGHT CENTER FOR COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Darrick Hamilton William A. Darity Jr. THE NEW SCHOOL DUKE UNIVERSITY November 2016 American Gothic, Washington, DC, 1942. Photograph by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright the Gordon Parks Foundation. ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE The nonprofit Urban Institute is dedicated to elevating the debate on social and economic policy. For nearly five decades, Urban scholars have conducted research and offered evidence-based solutions that improve lives and strengthen communities across a rapidly urbanizing world. Their objective research helps expand opportunities for all, reduce hardship among the most vulnerable, and strengthen the effectiveness of the public sector. ABOUT THE SAMUEL DUB OIS COOK CENTER ON S OCIAL EQUITY AT DUKE UNIVERSITY The Duke Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity is a scholarly collaborative engaged in the study of the causes and consequences of inequality and in the assessment and redesign of remedies for inequality and its adverse effects. Concerned with the economic, political, social, and cultural dimensions of uneven and inequitable access to resources, opportunity and capabilities, Cook Center researchers take a cross-national comparative approach to the study of human difference and disparity. Ranging from the global to the local, Cook Center scholars not only address the overarching social problem of general inequality, but they also explore social problems associated with gender, race, ethnicity, and religious affiliation. -

COXEY's CHALLENGE in the POPULIST MOMENT by Jerry Prout

COXEY'S CHALLENGE IN THE POPULIST MOMENT by Jerry Prout A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Committee: Director Department Chairperson Program Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: J 16,.)I;/} Spring Semester 2012 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Coxey‘s Challenge in the Populist Moment A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Jerry Prout Master of Arts American University, 1979 Master of Arts Duke University, 1972 Bachelor of Arts Westminster College, 1971 Director: Michael O‘Malley, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2012 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2012 Jerry Prout All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to Charles Henry Prout, Jr., who died on December 23, 2010, at the age of ninety. His lifelong insatiable curiosity, dedication to ideas, enthusiasm for life, and love of history provides the inspiration to never to stop searching for insight as revealed in our past. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In 2006 upon resuming the pursuit of a doctorate after a prolonged hiatus (1972), I needed plenty of inspiration and guidance. Members of George Mason University history faculty provided these. In doing so, they revealed just how dramatically the field had changed, and how much it had stayed the same. In her rigorous demands on a minor field statement, Dina Copelman reminded me of the obligations and boundaries of historical inquiry. With her enthusiasm and insight, Rosemarie Zagarri reinforced that this was the right path. -

515683 Chicago Law Review 78.4 R1.Ps

The University of Chicago Law Review Volume 78 Fall 2011 Number 4 © 2012 by The University of Chicago ARTICLES Reconstruction and the Transformation of Jury Nullification Jonathan Bressler† More than a century ago, the Supreme Court, invoking antebellum judicial precedent, held that juries no longer have the right to “nullify”—that is, to refuse to apply the law as given by the court. Today, however, in assessing the constitutionally protected right to criminal jury trial, the Supreme Court has emphasized originalism, delineating the right’s current boundaries by the Founding-era understanding of it. Relying on this Supreme Court jurisprudence, scholars and several federal judges have recently concluded that because Founding-era juries had the right to nullify, the right was beyond the authority of nineteenth-century judges to curtail and thus should be restored. But originalists who advocate restoration of the right to nullify are missing an important constitutional moment: Reconstruction. The Fourteenth Amendment fundamentally transformed constitutional criminal procedure, in the process altering the relationship between the federal government and localities and between federal judges and local juries. This Article (1) responds to what is an emerging consensus among these commentators that the Supreme Court’s prohibition of jury nullification cannot be justified on originalist or historical grounds and (2) provides new evidence of how the Fourteenth Amendment’s Framers, ratifiers, original interpreters, and original enforcers thought about juries, evidence that differs from the traditional perspective that the Reconstruction Congresses intended to empower juries. It finds that the Reconstruction Congresses understood the Fourteenth Amendment not to incorporate against the states the jury’s historic right to nullify, even as it incorporated a general right to jury trial.