Visual Representations of the Numinous: a Philosophical, Art Historical and Theological Inquiry 1780-1880

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Bibliography

6. The Closing Circle: 1880–1 Bibliography The bibliography contains works either consulted or quoted from in the text. Capitalisation of main words in older titles has generally been retained as rendered on the works’ title pages. Bibliographies: Barr, Susan. 1994. Norske offentlige samlinger med kulturhistorisk polarmateriale. Meddelelser nr. 134. Oslo: Norsk Polarinsttutt. Bring, Samuel E. 1954. Itineraria Svecana: Bibliografisk förteckning över resor i Sverige fram till 1950. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. Chartier, Daniel. 2007. A Bibliography on the Imagined North: Arctic, Winter, Antarctic. Montreal: Imaginaire Nord. Cordes, Fauno Lancaster. 2005. “Tekeli-li” or Hollow Earth Lives: A Bibliography of Antarctic Fiction. Online at: http://www.antarctic-circle.org/fauno.htm consulted 06.02.2013). Chavanne, Josef et. al. 1962. Die Literatur über die Polar-Regionen der Erde bis 1875. 1878; Amsterdam: Meridian Publishing Co. Holland, Clive. 1994. Arctic Exploration and Development c. 500 B.C. to 1915: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc. Karrow, Robert W., Jr. (ed.). 2000. The Gerald F. Fitzgerald Collection of Polar Books, Maps, and Art at The Newberry Library: A Catalogue. Compiled by David C. White and Patrick Morris. Chicago: The Newberry Library. King, H.G.R. 1989. The Arctic. World Bibliographical Series, vol. 99. Oxford: Clio Press. Meadows, Janice, William Mills and H.G.R. King. 1994. The Antarctic. World Bibliographical Series, vol. 171. Oxford: Clio Press. Polarlitteratur. 1925. Bokfortegnelse nr. 24. Oslo: Deichmanske bibliotek. Schiötz, Eiler. 1970 and 1986. Itineraria Norvegica: A Bibliography on Foreigners’ Travels in Norway until 1900. II vols. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. Verso l’estrema Thule: Italienske reiser på Nordkalotten før 1945. -

Concepts of Spirituality in 'Th Works of Robert Houle and Otto Rogers Wxth Special Consideration to Images of the Land

CONCEPTS OF SPIRITUALITY IN 'TH WORKS OF ROBERT HOULE AND OTTO ROGERS WXTH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO IMAGES OF THE LAND Nooshfar B, Ahan, BCom A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial filfillment of the requïrements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 6 December 2000 O 2000, Nooshfar B. Ahan Bibliothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibIiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada your me voue rélèreoca Our file Notre reMrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfomq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis examines the use of landscape motifs by two contemporary Canadian artists to express their spiritual aspirations. Both Robert Houle and Otto Rogers, inspired by the Canadian prairie landscape, employ its abstracted form to convey their respective spiritual ideas. -

Dmitri Alexeevpiano

Schumann Liszt’s transcriptions Dmitri Alexeev piano SMCCD 0275-276 DDD/STEREO 104.55 CD 1 TT: 41.06 Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856) 1 Blumenstück, op. 19 ................................................... 8.21 Symphonic Etudes, op. 13 and op. posth. 2 Thema. Andante ..................................................... 1.27 3 Etude I (Variation I). Un poco più vivo .................................... 1.13 4 Etude II (Variation II) .................................................. 2.41 5 Etude III. Vivace .................................................... 1.28 6 Etude IV (Variation III) ................................................ 0.59 7 Etude V (Variation IV) ................................................. 1.00 8 Etude VI (Variation V). Agitato .......................................... 0.59 9 Etude VII (Variation VI). Allegro molto .................................... 1.26 10 Posthumous Variation 1 ............................................... 0.55 11 Posthumous Variation 2 ............................................... 2.08 12 Posthumous Variation 3 ............................................... 1.54 13 Posthumous Variation 4 ............................................... 2.13 14 Posthumous Variation 5 ............................................... 1.57 15 Etude VIII (Variation VII) ............................................... 1.18 16 Etude IX. Presto possible .............................................. 0.38 17 Etude X (Variation VIII) ................................................ 0.45 18 Etude XI (Variation -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

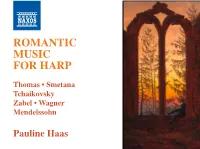

Romantic Music for Harp

ROMANTIC MUSIC FOR HARP Thomas • Smetana Tchaikovsky Zabel • Wagner Mendelssohn Pauline Haas 1 The Vision of a Dreamer by Pauline Haas A troubling landscape, the remains of an abbey, or maybe of a castle – the horizon in the distance stands out against the dusk. In the middle of the ruins, in the frame of an unglazed window, a young man is seated in profile. Is he dreaming? Is he doubting? Is he believing? The Dreamer is a journey of initiation: it is about Man travelling down his path of life pursued by his double, it is about an artist in pursuit of truth. I have contemplated this painting, seeing in it my own image as though in a mirror. I have created the image of this individual as a picture of my own dreams. I was his age when I made this recording – the age when one leaves childhood behind to enter the wider world and face up to oneself. I became conscious that the instrument lying against my shoulder, which had inspired so many poets and artists, but had been abandoned by musicians was, in my hands, like a blank page. I placed on my music stand, therefore, the traditional repertoire for the harp, other works considered inaccessible for the harpist, works which had long maintained a magical impact on me. I have woven a connecting thread between these works, nuancing the virgin whiteness of my page without managing to reach all the possible heights. Like a figure in a painting by Caspar David Friedrich this programme contemplates a distant horizon. -

The Landscape of Longing

Caspar David Friedrich^ the peculiar Romantic. The Landscape of Longing BY ANNE HOLLANDER nly nine oil paintings and exhibition de\oted t(.> Friedricb ever to ticeable thing abotit this mini-retro- eleven works on paper be moimted in tbis coiuitiy. It is possible spective is its consistency. Friedrich iiKikc lip the Metropolitan that many more Friedricbs still lurk in perfected his method by 1808 and O Mtiseiiin's current exhibi- the Soviet Union, unknown in tbe West, never changed it, even dining the peri- tion of Caspar David Fricdricli's works even in repiodnction; but for now we are od after his stroke in 1835, wben he from Russia; and thev are only mininiallv gi'eatly pleased to see these. worked very little. augmeiilfd by a lew engravings, owned They are few, and many are ver\' Friedricb never dated bis paintings, by ibe niiist'uin. wliicb were made by ibe small, aitbotigb two of tbem, meastir- and lie sbowed none of tbat obsession artist's brotber from some with development so com- of Friedricb's 180:i draw- mon to artists of his peri- ings. Housed far to the od and to others ever rear of tbe main floor in a since. Apparently lie bad small section ol tbe I.eb- no need to enact a \isible man wing, this sbow must figbt for artistic teriitorA, be sotiglit otit, but it is im- to be seen to be struggling portant despite its small steadily along insicle the si/e and ascetic Haxor. C.as- meditmi itself, to give per- par David Friedricb (I 774- pettial evidence of bis per- 1H40) is now generally ac- sonal battle witb tbe in- knowledged as a great tractable eye, tbe pesky Romantic painter, and materials, tbe superior predecessors, (he pre.sent space lias been made for ri\als, with aljiding artistic bim beside I inner, (ieri- problems and new selt- cault, Blake, and Goya on imposed technical tasks, tbe roster of Eaily Nine- vvitli dominant opinion, teenth Centnry Originals. -

The Music and Musicians of St. James Cathedral, Seattle, 1903-1953: the First 50 Years

THE MUSIC AND MUSICIANS OF ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL, SEATTLE, 1903-1953: THE FIRST 50 YEARS CLINT MICHAEL KRAUS JUNE 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of figures................................................................................................................... iii List of tables..................................................................................................................... iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 – Music at Our Lady of Good Help and St. Edward’s Chapel (1890- 1907)..................................................................................................................5 Seattle’s temporary cathedrals......................................................................5 Seattle’s first cathedral musicians ................................................................8 Alfred Lueben..................................................................................................9 William Martius ............................................................................................14 Organs in Our Lady of Good Help ............................................................18 The transition from Martius to Ederer.......................................................19 Edward P. Ederer..........................................................................................20 Reaction to the Motu Proprio........................................................................24 -

František Kupka: Sounding Abstraction – Musicality, Colour and Spiritualism

Issue No. 2/2019 František Kupka: Sounding Abstraction – Musicality, Colour and Spiritualism Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff, PhD, Chief Curator, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki Also published in Anne-Maria Pennonen, Hanne Selkokari and Lene Wahlsten (eds.), František Kupka. Ateneum Publications Vol. 114. Helsinki: Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum 2019, 11–25. Transl. Tomi Snellman The art of František Kupka (1871–1957) has intrigued artists, art historians and exhibition visitors for many decades. Although nowadays Kupka’s name is less well known outside artistic circles, in his day he was one of the artists at the forefront in creating abstract paintings on the basis of colour theory and freeing colours from descriptive associations. Today his energetic paintings are still as enigmatic and exciting as they were in 1912, when his completely non- figurative canvases, including Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colours and Amorpha, Warm Chromatics, created a scandal when they were shown in the Salon d’Automne in Paris. It marked a turning point in many ways, not least in the decision of the Gaumont Film Company to use Kupka’s abstract works for the news in cinemas in France, Germany, the United States and England.1 And as we will see, Kupka’s far-reaching shift to abstraction was a long process which grew partly out of his childhood interest in spiritualism and partly from Symbolist and occultist ideas to crystallise into the concept of an art which could be seen, felt and understood on a more multisensory basis. Kupka’s art reflects the idea of musicality in art, colour and spiritualism. -

Class 10: Between Reason and Romance

Class 10: Between Reason and Romance A. William Blake and the Crisis of Faith 1. Title Slide 1 (Blake: Newton) 2. Phillips: William Blake (1807, London, National Portrait Gallery) I have shown pictures before by William Blake (1757–1827)—his Ezekiel in last week’s class, for instance. He keeps on cropping up whenever you look at the turn of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, the passage from Reason to Romance. And yet he is difficult to fit into any continuity before or after: a maverick, a genius, a mystic, or simply a madman. I struggled a lot with the shape of today’s class, until I realize that it was this quality—Blake’s refusal to fit in—that made him such a perfect entry into what appears to have been a very troubled time. 3. Blake: “The Lamb,” video reading 4. Blake: “The Lamb” (1789, Library of Congress) Blake was a Christian—or at least he began as one. When looking at his early poetry collection, Songs of Innocence (1789), we might think of his faith as rather simplistic, as exemplified, for instance, in his poem “The Lamb.” The images in this video enhance the poem’s apparent naiveté, though hardly any more than Blake’s own hand-tinted engraving. Blake apprenticed as an engraver before studying at the Royal Academy; his work as a poet is entirely that of an amateur, though he published his poetry and art together as integrated artwork. 5. Blake: “The Tyger,” video reading by Tom O’Bedlam 6. Blake: “The Tyger,” detail (1795, British Museum) Blake followed up Songs of Innocence in 1794 with Songs of Experience, in which the naïve images are replaced by altogether more disturbing ones. -

An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature,” the New York Times, May 22, 2009

Genocchio, Benjamin. “An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature,” The New York Times, May 22, 2009. An Eye for Landscapes That Transcend Nature One’s lasting impression of the April Gornik exhibition at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington is the sheer virtuosity of the pictures. They glow with mystery and grandeur. Landscape painting of this quality is not often seen on Long Island. Assembled by Kenneth Wayne, the museum’s chief curator, the show focuses on the artist’s powerful, large-scale oil paintings. There are a dozen pictures, created roughly from the late 1980s to the present, nicely displayed in two of the Heckscher’s newly renovated galleries. The removal of a false ceiling in them has allowed the museum to accommodate much larger works than it could before. New Horizons. The large-scale oil paintings by April Gornik on display at the Heckscher include “Sun Storm Sea” (2005). At 56, Ms. Gornik is already a painter of eminence. She has had shows around the world, and her work is in several major museum collections, including those of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. I would place her among the top landscape artists working in America today. That this is Ms. Gornik’s first major solo exhibition on Long Island in more than 15 years seems an oversight, especially given that she lives part of the year in Suffolk County. But better late than never, for there are probably dozens of artists living and working on Long Island who are deserving of shows. -

Humanities (World Focus) Course Outline

Guiding Document: Humanities Course Outline Humanities (World Focus) Course Outline The Humanities To study humanities is to look at humankind’s cultural legacy-the sum total of the significant ideas and achievements handed down from generation to generation. They are not frivolous social ornaments, but rather integral forms of a culture’s values, ambitions and beliefs. UNIT ONE-ENLIGHTENMENT AND COMPARATIVE GOVERNMENTS (18th Century) HISTORY: Types of Governments/Economies, Scientific Revolution, The Philosophes, The Enlightenment and Enlightenment Thinkers (Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, Voltaire, Jefferson, Smith, Beccaria, Rousseau, Franklin, Wollstonecraft, Hidalgo, Bolivar), Comparing Documents (English Bill of Rights, A Declaration of the Rights of Man, Declaration of Independence, US Bill of Rights), French Revolution, French Revolution Film, Congress of Vienna, American Revolution, Latin American Revolutions, Napoleonic Wars, Waterloo Film LITERATURE: Lord of the Flies by William Golding (summer readng), Julius Caesar by Shakespeare (thematic connection), Julius Caesar Film, Neoclassicism (Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedie excerpt, Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man”), Satire (Oliver Goldsmith’s Citizen of the World excerpt, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels excerpt), Birth of Modern Novel (Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe excerpt), Musician Bios PHILOSOPHY: Rene Descartes (father of philosophy--prior to time period), Philosophes ARCHITECTURE: Rococo, Neoclassical (Jacques-Germain Soufflot’s Pantheon, Jean- Francois Chalgrin’s Arch de Triomphe)