The Netherlands Overview and Introduction There Are Three Main Types of Insolvency Proceedings in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virgin Atlantic

Virgin Atlantic Cryptocurrencies: Provisional Lottie Pyper considers the 2020 and beyond Liquidation and guidance given on the first Robert Amey, with Restructuring: Jonathon Milne of The Cayman Islands restructuring plan under Conyers, Cayman, and Hong Kong Part 26A of the Companies on recent case law Michael Popkin of and developments Campbells, takes a Act 2006 in relation to cross-border view cryptocurrencies A regular review of news, cases and www.southsquare.com articles from South Square barristers ‘The set is highly regarded internationally, with barristers regularly appearing in courts Company/ Insolvency Set around the world.’ of the Year 2017, 2018, 2019 & 2020 CHAMBERS UK CHAMBERS BAR AWARDS +44 (0)20 7696 9900 | [email protected] | www.southsquare.com Contents 3 06 14 20 Virgin Atlantic Cryptocurrencies: 2020 and beyond Provisional Liquidation and Lottie Pyper considers the guidance Robert Amey, with Jonathon Milne of Restructuring: The Cayman Islands given on the first restructuring plan Conyers, Cayman, on recent case law and Hong Kong under Part 26A of the Companies and developments arising from this Michael Popkin of Campbells, Act 2006 asset class Hong Kong, takes a cross-border view in these two off-shore jurisdictions ARTICLES REGULARS The Case for Further Reform 28 Euroland 78 From the Editors 04 to Strengthen Business Rescue A regular view from the News in Brief 96 in the UK and Australia: continent provided by Associate South Square Challenge 102 A comparative approach Member Professor Christoph Felicity -

Corporate Restructuring

JW ACCOUNTANTS – SPECIALIST ADVISORY PRACTICE CORPORATE RESTRUCTURING AN ASSESSMENT OF PART 9 vs PART 10 of the COMPANIES ACT, 2014 Joseph Walsh +353-(0)1-96 96 888 38 Grand Canal Street Upper www.jwaccountants.ie Dublin 4 Managing Director [email protected] Debt Restructuring Options Debt Restructuring Options - where can companies look for protection, an assessment of Part 9 versus Part 10 of the Companies Act 2014. Over the past number of weeks there has been unprecedented disruption to business throughout the world presenting challenging times for most companies operating in Ireland. In this post Joe Walsh of JW Accountants Ireland considers the restructuring options currently available to companies in Ireland under Part 9 and Part 10 of the Companies Act 2014. INTRODUCTION As talk turns to how the economy can be reopened, businesses face a number of challenges and with the level of uncertainty that exists the new norm is working capital management and assessment of business plans on an almost daily basis. The key considerations for businesses at this time will include: a) The health and well-being of employees and customers b) New business model and how to start back up c) Legacy debt d) Debtor Collections and the impact on cashflow Part 9 of the Companies Act, 2014 A scheme of arrangement, pursuant to Part 9 of the Companies Act 2014, deals with reorganisations, acquisitions, mergers and divisions, and it provides a mechanism for a company to enter into a scheme of arrangement with its members and / or its creditors. In assessing this section of the legislation, I have focused on the option of a scheme of arrangement under Part 9 (“Part 9 Scheme”) for an insolvent company to address legacy debt. -

Directors' Duty to Creditors of a Financially Distressed Company: a Perspective from Across the Pond Donna W

Journal of Business & Technology Law Volume 1 | Issue 2 Article 13 Directors' Duty to Creditors of a Financially Distressed Company: A Perspective from Across the Pond Donna W. McKenzie-Skene Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jbtl Part of the Bankruptcy Law Commons, and the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Donna W. McKenzie-Skene, Directors' Duty to Creditors of a Financially Distressed Company: A Perspective from Across the Pond, 1 J. Bus. & Tech. L. 499 (2007) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jbtl/vol1/iss2/13 This Articles & Essays is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Business & Technology Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DONNA W. MCKENZIE-SKENE* Directors' Duty to Creditors of a Financially Distressed Company: A Perspective from Across the Pond I. INTRODUCTION THERE HAS RECENTLY BEEN A REVIVAL OF INTEREST IN THE subject of the directors' duty to creditors where the company is financially distressed,' and it was consid- ered in some detail by the Company Law Review Steering Group, which was set up by the British government to review core company law in 19982 and reported in 2001? Although the duty is now generally regarded as well-established in princi- ple,4 there are important aspects of it that remain unclear, and the role of the duty in modern law has been questioned. This Article briefly outlines the development Senior Lecturer, School of Law, University of Aberdeen. -

British Virgin Islands Harney Westwood & Riegels LLP 3Rd Floor 1 Pemberton Row London EC4A 3BG United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 3752 3600 Fax: +44 20 3752 3695

INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. Enforceability of the Liquidation, Setoff, Netting and Credit Support Provisions of Certain Futures Account Agreements and a Cleared Derivatives Addendum upon a Customer’s Default or Insolvency, and Enforceability of Certain Offset Provisions Applicable Prior to a Customer’s Default or Insolvency 1 October 2020 British Virgin Islands Harney Westwood & Riegels LLP 3rd Floor 1 Pemberton Row London EC4A 3BG United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 3752 3600 Fax: +44 20 3752 3695 1 October 2020 [email protected] +44 203 752 3640 019603.0057 International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. 360 Madison Avenue, 16th Floor New York, NY10017 Futures Industry Association 2001 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W. Suite 600 Washington, D.C. 20006 Dear Sirs Enforceability of the Liquidation, Setoff, Netting and Credit Support Provisions of Certain Futures Account Agreements and a Cleared Derivatives Addendum upon a Customer’s Default or Insolvency, and Enforceability of Certain Offset Provisions Applicable Prior to a Customer’s Default or Insolvency: British Virgin Islands 1 Introduction 1.1 We have been asked to advise the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. (ISDA) and the Futures Industry Association (FIA) on certain issues with respect to the operation of the U.S. law trusts under which customer assets are held by a futures commission merchant (FCM) and the enforceability of the liquidation and credit support provisions of certain futures account agreements and a Cleared Derivatives Addendum upon a customer’s default or insolvency. 1.2 This opinion is given with respect to Futures Transactions and Cleared Derivatives Transactions of the types described in Appendix A (Covered Transactions) entered into under Covered Base Agreements and CDAs by customers organised in the British Virgin Islands as any of the types described in Appendix B (including British Virgin Islands branches of entities organised outside the British Virgin Islands). -

Corporate Recovery & Insolvency 2019

ICLG The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Corporate Recovery & Insolvency 2019 13th Edition A practical cross-border insight into corporate recovery and insolvency work Published by Global Legal Group, in partnership with INSOL International and the International Insolvency Institute, with contributions from: Ali Budiardjo, Nugroho, Reksodiputro Macfarlanes LLP Allen & Gledhill LLP McCann FitzGerald AZB & Partners Miyetti Law Barun Law LLC Mori Hamada & Matsumoto Benoit Chambers Noerr LLP Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP De Pardieu Brocas Maffei Aarpi Pirola Pennuto Zei & Associati Dirican | Gozutok SCA LEGAL, SLP ENGARDE Attorneys at law Schindler Rechtsanwälte GmbH Gall SOLCARGO Gilbert + Tobin Stibbe Hannes Snellman Attorneys Synum ADV INSOL International Thornton Grout Finnigan LLP International Insolvency Institute (III) Zepos & Yannopoulos Kennedys Law Office Waly & Koskinen Ltd. Lenz & Staehelin Loyens & Loeff Luxembourg The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Corporate Recovery & Insolvency 2019 Editorial Chapters: 1 INSOL’s Role Shaping the Future of Insolvency – Adam Harris, INSOL International 1 2 International Insolvency Institute – An Overview – Alan Bloom, International Insolvency Institute (III) 4 General Chapters: 3 Directors and Insolvency: Dangers and Duties – Jat Bains & Paul Keddie, Macfarlanes LLP 7 Contributing Editor Jat Bains, Macfarlanes LLP 4 “Cross”-Border Wall? Not for U.S. Recognition of Foreign Insolvency Proceedings – Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP 12 Publisher Rory Smith Country Question and Answer Chapters: Sales Director Florjan Osmani 5 Australia Gilbert + Tobin: Dominic Emmett & Alexandra Whitby 18 Account Director 6 Austria Schindler Rechtsanwälte GmbH: Martin Abram & Florian Cvak 26 Oliver Smith Senior Editors 7 Belgium Stibbe: Pieter Wouters & Paul Van der Putten 32 Caroline Collingwood 8 Bermuda Kennedys: Alex Potts QC & Mark Chudleigh 38 Rachel Williams Sub Editor 9 Canada Thornton Grout Finnigan LLP: Leanne M. -

An Outline of the EU Regulation on Insolvency Proceedings (P.A

An Outline of The EU Regulation on Insolvency Proceedings Sandy Shandro Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer June 2003 (000000-0000) CONTENTS PART ONE - A GUIDE T O THE REGULATION.................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................1 SCOPE OF APPLIC ATION OF THE REGULATION ............................................................2 PRINCIPAL PROVISIONS OF THE REGULATION.............................................................4 IMPACT OF THE REGULATION.....................................................................................9 PART TWO – A NOTE ON BRAC RENT–A-CAR INTERNATIONAL INC..................................................................................................................12 LD553456/6+ (000000-0000) Page i PART ONE - A GUIDE T O THE REGULATION INTRODUCTION On 29 May 2000 the EU Council adopted the Regulation on Insolvency Proceedings (the Regulation). The Regulation came into force on 31 May 2002. To a great extent, the Regulation replicates the text of the draft EC convention on insolvency proceedings 1995 (the Convention). The Convention failed to receive the required unanimous support as, due to the underlying territorial concerns over Gibraltar, the UK failed to sign within the prescribed time. The Convention therefore lapsed on 23 May 1996. The adoption of the Regulation in 2000 was welcome news for the member states of the EU, some of which had been working towards pan-European consensus on insolvency issues for the past 30 years. The Regulation aims to introduce uniform conflicts of law rules for insolvency proceedings and connected judgments. This will help address the difficulties that arise when an insolvency involves a number of different European jurisdictions. It does not, however, seek to harmonise substantive law or policy as between different EU countries. LD553456/6+ (000000-0000) Page 1 SCOPE OF APPLICATION OF THE REGULATION The Regulation came into force on 31 May 2002. -

Restructuring Update: UK Budget and Increase of “Prescribed Part”

Kirkland Alert Restructuring Update: UK Budget and Increase of “Prescribed Part” 11 March 2020 Today’s UK Budget saw two changes particularly relevant for the restructuring and insolvency market: the delay of the planned return of HMRC as a preferential creditor and the temporary abolition of business rates for the retail, leisure and hospitality sectors below a certain (low) threshold. Separately, the government has published legislation increasing the amount of the “prescribed part” — a ring- fenced sum made available to unsecured creditors from oating charge realisations. At a glance HMRC’s return as preferential creditor: The return of HMRC as a secondary preferential creditor in insolvency proceedings (in respect of certain taxes) will be delayed until 1 December 2020. Once implemented, this reform is expected to increase HMRC’s inuence in distressed situations and decrease creditors’ appetite to lend based on oating charge security (or on an unsecured basis). Business rates: Abolished for rms in the retail, leisure and hospitality sectors for properties with a rateable value below £51,000, for one year. Prescribed part: The ring-fenced sum made available to unsecured creditors from oating charge realisations will increase from £600,000 to £800,000 where the relevant oating charge was created on or after 6 April 2020.1 HMRC’s return as preferential creditor The Budget announced that the government will delay plans to install HMRC as secondary preferential creditor in an insolvency for debts relating to certain taxes paid by employees and customers. The measures will now take eect in respect of formal insolvencies commencing from 1 December 2020, rather than 6 April 2020 as previously announced. -

A Tale of Two Crowns

Doc Title A Tale of Two Crowns A - Front Page two line title ARTICLE A Tale of Two Crowns Coronaviruses are named for the crown-like spikes on their surface. The combination of the “Two Crowns” - COVID-19 alongside the return of Crown Preference - will result in a significantly more material impact than was originally intended, given the COVID-19 VAT deferral scheme which has resulted in over £28bn of cumulative VAT deferrals. In this briefing memo, Lisa Rickelton (Restructuring) and Alistair Winning (Tax) The New Waterfall1 discuss the practical consequences of Crown Preference, alongside crown set- off rules in the context of insolvency, and provide worked examples, giving a A. Preferential Creditors deeper dive into the issues raised by VAT groups in which members have joint (Schedule 6): primarily employee related2 and several liability. B. Secondary Preferential Summary of Provisions Creditors: Priority Taxes3 C. Prescribed Part4 The return of Crown Preference had been due to come into force on 6 April 2020; however, this was delayed to 1 December 2020 due to COVID-19. D. Floating Charge Holders HMRC will rank ahead of floating charge creditors and unsecured creditors in E. Unsecured Creditors respect of certain taxes which are collected by a company on behalf of HMRC – 1. In respect of floating charge assets primarily VAT, PAYE and employees’ National Insurance Contributions 2. Schedule 6 of the Insolvency Act – e.g. certain unpaid wages, certain pension (“Priority Taxes”). Prior to 1 December 2020, these taxes rank as unsecured. contributions and holiday pay 3. VAT, PAYE, Employees’ National Insurance Contributions, student loan deductions Key Points to Note: and Construction Industry Scheme deductions — The new waterfall applies to all insolvencies which commence from 1 4. -

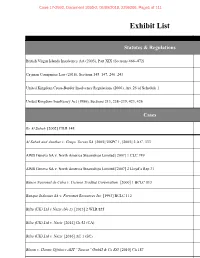

Exhibit List

Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page1 of 111 Exhibit List Statutes & Regulations British Virgin Islands Insolvency Act (2003), Part XIX (Sections 466–472) B Cayman Companies Law (2016), Sections 145–147, 240–243 United Kingdom Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations (2006), Art. 25 of Schedule 1 United Kingdom Insolvency Act (1986), Sections 213, 238–239, 423, 426 Cases Re Al Sabah [2002] CILR 148 Al Sabah and Another v. Grupo Torras SA [2005] UKPC 1, [2005] 2 A.C. 333 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 1 CLC 749 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 31 Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Cosmos Trading Corporation [2000] 1 BCLC 813 Banque Indosuez SA v. Ferromet Resources Inc [1993] BCLC 112 Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir (No 2) [2013] 2 WLR 825 Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2014] Ch 52 (CA) Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2016] AC 1 (SC) Bloom v. Harms Offshore AHT “Taurus” GmbH & Co KG [2010] Ch 187 Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page2 of 111 Exhibit List Cases, continued Re Paramount Airways Ltd [1993] Ch 223 Picard v. Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities LLC BVIHCV140/2010 B Rubin v. Eurofinance SA [2013] 1 AC 236; [2012] UKSC 46 Singularis Holdings Ltd v. PricewaterhouseCoopers [2014] UKPC 36, [2015] A.C. 1675 Stichting Shell Pensioenfonds v. Krys [2015] AC 616; [2014] UKPC 41 Other Authorities McPherson’s Law of Company Liquidation (4th ed. 2017) Anthony Smellie, A Cayman Islands Perspective on Trans-Border Insolvencies and Bankruptcies: The Case for Judicial Co-Operation , 2 Beijing L. -

LEND13 E-Edition Real Estate 2006

ICLG The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Lending and Secured Finance 2013 1st Edition challenges thetitanic Navigate of today’s global financial markets. financial global today’s bingham.com Attorney Advertising © 2013 Bingham McCutchen LLP One Federal Street, Boston MA 02110 T. 617.951.8000 Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Bingham McCutchen® Bingham McCutchen (London) LLP, a Massachusetts limited liability partnership authorised and regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (registered number: 00328388), is the legal entity which operates in the UK as Bingham. A list of the names of its partners and their qualifications is open for inspection at the address above. All partners of Bingham McCutchen (London) LLP are either solicitors or registered foreign lawyers. The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Lending and Secured Finance 2013 General Chapters: 1 An Introduction to Legal Risk and Structuring Cross-Border Lending Transactions - Thomas Mellor & Marc Rogers Jr., Bingham McCutchen LLP 1 2 Fashions in European Leveraged Finance – Developments in European Funding Models - Ian Borman, SJ Berwin LLP 6 Contributing Editor 3 Acquisition Financing in the United States: Outlook Improved - Geoffrey R. Peck, Morrison & Foerster LLP 9 Thomas Mellor, Bingham McCutchen LLP 4 Subscription Credit Facilities: Key Features, Documentation Issues and Credit Concerns - Account Managers Greg B. Cioffi & Jeff Berman, Seward & Kissel LLP 14 Beth Basssett, Dror Levy, 5 Loan Syndications and Trading: An Overview of the Syndicated Loan Market - Maria Lopez, Florjan Bridget Marsh & Ted Basta, The Loan Syndications and Trading Association 19 Osmani, Oliver Smith, Rory Smith 6 Loan Market Association – An Overview - Nigel Houghton, Loan Market Association 25 Sales Support Manager Toni Wyatt Country Question and Answer Chapters: Sub Editors 7 Argentina Marval, O’Farrell & Mairal: Juan M. -

Restructuring Across Borders

Restructuring Across Borders England and Wales: Administration | October 2020 allenovery.com Contents 3 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 9 10 11 2 Restructuring across borders: England and Wales: Administration | October 2020 allenovery.com Introduction Administration is the collective rehabilitation procedure under which a company may be rescued, reorganised or its business or assets realised under the protection of a statutory moratorium, providing a protective breathing space from creditor action. It is loosely modelled on the U.S. Chapter 11 procedure, but it is dangerous to take this analogy too far. Each company in a group must be dealt with individually. For the duration of the administration, the affairs, business and property of the company are managed by one or more licensed insolvency practitioners, known as administrators. Under the EU Regulation on Insolvency Proceedings 2015 (Regulation (EU) 2015/848), administration is listed in Annex A and is, therefore, available as both a main insolvency proceeding and a secondary insolvency proceeding. Appointment There are three ways to appoint an administrator: − by application to the court; The effect of the appointment is the same in each case. − out of court, by the holder of a “qualifying floating charge”; or While a company is subject to the statutory moratorium under Part A1 of the Insolvency Act 1986, no administration application − out of court, by the company or its directors. may be made (except by the directors) and no out-of-court A “qualifying floating charge” means security, which includes appointment can be made by anyone. a floating charge, over the whole or substantially the whole of the assets of the company and which meets certain drafting requirements. -

Global Restructuring & Insolvency Guide

Global Restructuring & Insolvency Guide Taiwan Overview and Introduction Taiwan, the Republic of China (“ROC”), has a codified system of laws. The major codes are the Civil Code, the Criminal Code, the Civil Procedure Code and the Criminal Procedure Code. The content of the codes is drawn from the laws of other countries with similar codified systems, e.g. Germany and Japan, and from traditional Chinese laws. The supreme law of Taiwan is its constitution. The judicial system is composed of three tiers: the Supreme Court, the High Court and the District Court. Judges decide all cases and there is no provision for jury trials. In Taiwan, insolvency denotes a state in which a debtor is unable to meet its debts when the debts are due. Applicable Legislation There are several mechanisms dealing with insolvency. Articles 282 to 314 of the Taiwan Company Law provide for court-supervised restructuring of potentially viable but insolvent companies. Under the Taiwan Bankruptcy Law, a debtor could be adjudicated bankrupt upon a petition either by the debtor or a creditor when the debtor is unable to repay its debts. If the court declares to cease the reorganisation process of a corporate body, in case the conditions for bankruptcy are met, the court may, ex officio, render a ruling to declare the company bankrupt. While the Taiwan Bankruptcy Law is also applicable to the bankruptcy of an individual, the Consumer Insolvency Procedure Act (the “CIPA”) deals with insolvency proceedings for an individual debtor with no business activities or a monthly sales turnaround below TWD 200,000 for five years.