Soccer in America: a Story of Marginalization Andrei S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Record Book 5 Single-Season Records

PROGRAM RECORDS TEAM INDIVIDUAL Game Game Goals .......................................................11 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Goals .................................................. 5, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 ............................................................11 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 Assists ................................................. 4, Damian Silvera vs. UNC, 9/27/92 Assists ......................................................11 vs. Virginia Tech, 9/14/94 ..................................................... 4, Richie Williams vs. VCU, 9/13/89 Points .................................................................... 30 vs. VCU, 9/13/89 ........................................... 4, Kris Kelderman vs. Charleston, 9/10/89 Goals Allowed .................................................12 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 ...........................................4, Chick Cudlip vs. Wash. & Lee, 11/13/62 Margin of Victory ....................................11-0 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Points ................................................ 10, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 Fastest Goal to Start Match .........................................................11-0 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 .................................:09, Alecko Eskandarian vs. American, 10/26/02* Margin of Defeat ..........................................12-0 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 Largest Crowd (Scott) .......................................7,311 vs. Duke, 10/8/88 *Tied for 3rd fastest in an NCAA Soccer Game Largest Crowd (Klöckner) ......................7,906 -

Netherlands in Focus

Talent in Banking 2015 The Netherlands in Focus UK Financial Services Insight Report contents The Netherlands in Focus • Key findings • Macroeconomic and industry context • Survey findings 2 © 2015 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Key findings 3 © 2015 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Attracting talent is difficult for Dutch banks because they are not seen as exciting, and because of the role banks played in the financial crisis • Banking is less popular among business students in the Netherlands than in all but five other countries surveyed, and its popularity has fallen significantly since the financial crisis • Banks do not feature in the top five most popular employers of Dutch banking students; among banking-inclined students, the three largest Dutch banks are the most popular • The top career goals of Dutch banking-inclined students are ‘to be competitively or intellectually challenged’ and ‘to be a leader or manager of people’ • Dutch banking-inclined students are much less concerned with being ‘creative/innovative’ than their business school peers • Dutch banking-inclined students want ‘leadership opportunities’ and leaders who will support and inspire them, but do not expect to find these attributes in the banking sector • Investment banking-inclined students have salary expectations that are significantly higher than the business student average • Banks in the Netherlands are failing to attract female business students; this is particularly true of investment banks 4 © 2015 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Macroeconomic and industry context 5 © 2015 Deloitte LLP. All rights reserved. Youth unemployment in the Netherlands has almost doubled since the financial crisis, but is relatively low compared to other EMEA countries Overall and youth unemployment, the Netherlands, 2008-2014 15% 10% 5% 0% 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Overall Youth (Aged 15-24) 6 Source: OECD © 2015 Deloitte LLP. -

The Labor Agreements Between UAW and the Big Three Automakers- Good Economics Or Bad Economics? John J

Journal of Business & Economics Research – January, 2009 Volume 7, Number 1 The Labor Agreements Between UAW And The Big Three Automakers- Good Economics Or Bad Economics? John J. Lucas, Purdue University Calumet, USA Jonathan M. Furdek, Purdue University Calumet, USA ABSTRACT On October 10, 2007, the UAW membership ratified a landmark, 456-page labor agreement with General Motors. Following pattern bargaining, the UAW also reached agreement with Chrysler LLC and then Ford Motor Company. This paper will examine the major provisions of these groundbreaking labor agreements, including the creation of the Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association (VEBA), the establishment of a two tier wage structure for newly hired workers, the job security provisions, the new wage package for hourly workers, and the shift to defined contribution plans for new hires. The paper will also provide an economic analysis of these labor agreements to consider both if the “Big Three” automakers can remain competitive in the global market and what will be their impact on the UAW and its membership. Keywords: UAW, 2007 Negotiations, Labor Contracts BACKGROUND he 2007 labor negotiations among the Big Three automakers (General Motors, Chrysler LLC, and Ford Motor) and the United Autoworkers (UAW) proved to be historic, as well as controversial as they sought mutually to agree upon labor contracts that would “usher in a new era for the auto Tindustry.” Both parties realized the significance of attaining these groundbreaking labor agreements, in order for the American auto industry to survive and compete successfully in the global economy. For the UAW, with its declining membership of approximately 520,000, that once topped 1.5 million members, a commitment from the Big Three automakers for product investments to protect jobs and a new health care trust fund were major goals. -

Major League Soccer-Historie a Současnost Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra sportovních her Major League Soccer-historie a současnost Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Pavel Vacenovský Zdeněk Bezděk TVS/Trenérství Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brně dne 24. května 2013 podpis Děkuji vedoucímu bakalářské práce Mgr. Pavlu Vacenovskému, za podnětné rady, metodické vedení a připomínky k této práci. Úvod ........................................................................................................................ 6 1. FOTBAL V USA PŘED VZNIKEM MLS .................................................. 8 2. PŘÍPRAVA NA ÚVODNÍ SEZÓNU MLS ............................................... 11 2.1. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 17. října 1995..................................... 12 2.2. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 18. října 1995..................................... 14 2.3. První sponzoři MLS ............................................................................... 15 2.4. Platy Marquee players ............................................................................ 15 2.5. Další události v roce 1995 ...................................................................... 15 2.6. Drafty MLS ............................................................................................ 16 2.6.1. 1996 MLS College Draft ................................................................. 17 2.6.2. 1996 MLS Supplemental Draft ...................................................... -

MLS Game Guide

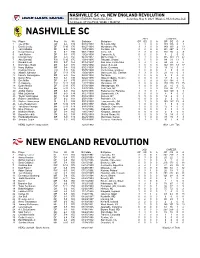

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

CUSTOM CONTENT an Industry in Wealth- Best NYC’S Leading Transformation: Management Venue Women Corporate Registry Guide Lawyers Accounting P

CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS NEW YORK BUSINESS® SPECIAL ISSUE | PRICE $49.95 © 2017 CRAIN COMMUNICATIONS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED NEWSPAPER VOL. XXXIII, NOS. 51–52 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM BONUS: CUSTOM CONTENT An industry in Wealth- Best NYC’s leading transformation: management venue women Corporate registry guide lawyers accounting P. 38 P. 50 P. 68 P. 23 CV1_CV4_CN_20171218.indd 1 12/15/17 3:51 PM NEW THE BEST JUST GOT BETTER NEW! HIGHER SPEEDS FOR ONLY $ 99 /mo, when 100Mbps 44 bundled* NO TAXES • NO HIDDEN FEES PLUS, GET ADVANCED SPECTRUM BUSINESS VOICE FOR ONLY $ 99 /mo, 29 per line** NO ADDED TAXES Switch to the best business services — all with NO CONTRACTS. Call 866.502.3646 | Visit Business.Spectrum.com Limited-time oer; subject to change. Qualified new business customers only. Must not have subscribed to applicable services within the previous 30 days and have no outstanding obligation to Charter.*$44.99 Internet oer is for 12 months when bundled with TV or Voice and includes Spectrum Business Internet Plus with 100Mbps download speeds, web hosting, email addresses, security suite, and cloud backup. Internet speed may not be available in all areas. Actual speeds may vary. Charter Internet modem is required and included in price; Internet taxes are included in price except where required by law (TX, WI, NM, OH and WV); installation and other equipment taxes and fees may apply. **$29.99 Voice oer is for 12 months and includes one business phone line with calling features and unlimited local and long distance within the U.S., Puerto Rico, and Canada. -

Will American Football Ever Be Popular in the Rest of the World? by Mark Hauser , Correspondent

Will American Football Ever Be Popular in the Rest of the World? By Mark Hauser , Correspondent Will American football ever make it big outside of North America? Since watching American football (specifically the NFL) is my favorite sport to watch, it is hard for me to be neutral in this topic, but I will try my best. My guess is that the answer to this queson is yes, however, I think it will take a long me – perhaps as much as a cen‐ tury. Hence, there now seems to be two quesons to answer: 1) Why will it become popular? and 2) Why will it take so long? Here are some important things to consider: Reasons why football will catch on in Europe: Reasons why football will struggle in Europe: 1) It has a lot of acon and excing plays. 1) There is no tradion established in other countries. 2) It has a reasonable amount of scoring. 2) The rules are more complicated than most sports. 3) It is a great stadium and an even beer TV sport. 3) Similar sports are already popular in many major countries 4) It is a great for beng and “fantasy football” games. (such as Australian Rules Football and Rugby). 5) It has controlled violence. 4) It is a violent sport with many injuries. 6) It has a lot of strategy. 5) It is expensive to play because of the necessary equipment. 7) The Super Bowl is the world’s most watched single‐day 6) Many countries will resent having an American sport sporng event. -

2017 United Soccer League Media Guide

Table of Contents LEAGUE ALIGNMENT/IMPORTANT DATES ..............................................................................................4 USL EXECUTIVE BIOS & STAFF ..................................................................................................................6 Bethlehem Steel FC .....................................................................................................................................................................8 Charleston Battery ......................................................................................................................................................................10 Charlotte Independence ............................................................................................................................................................12 Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC .......................................................................................................................................14 FC Cincinnati .................................................................................................................................................................................16 Harrisburg City Islanders ........................................................................................................................................................18 LA Galaxy II ..................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

Young American Sports Fans

Leggi e ascolta. Young American sports fans American football Americans began to play football at university in the 1870s. At the beginning the game was like rugby. Then, in 1882, Walter Camp, a player and coach, introduced some new rules and American Football was born. In fact, Walter Camp is sometimes called the Father of American Football. Today American football is the most popular sport in the USA. A match is only 60 minutes long, but it can take hours to complete because they always stop play. The season starts in September and ends in February. There are 11 players in a team and the ball looks like a rugby ball. ‘I play American football for my high school team. We play most Friday evenings. All our friends and family come to watch the games and there are hundreds of people at the stadium. The atmosphere is fantastic! High Five Level 3 . Culture D: The USA pp. 198 – 199 © Oxford University Press PHOTOCOPIABLE In my free time I love watching professional football. My local team is the Green Bay Packers. It’s difficult to get a ticket for a game, but I watch them on TV.’ Ice hockey People don’t agree on the origins of ice hockey. Some people say that it’s a Native American game. Other people think that immigrants from Iceland invented ice hockey and that they brought the game to Canada in the 19th century. Either way, ice hockey as we know it today was first played at the beginning of the 20th century. The ice hockey season is from October to June. -

The Soccer Diaries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters Spring 2014 The oS ccer Diaries Michael J. Agovino Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Agovino, Michael J., "The ocS cer Diaries" (2014). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 271. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/271 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. the soccer diaries Buy the Book Buy the Book THE SOCCER DIARIES An American’s Thirty- Year Pursuit of the International Game Michael J. Agovino University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London Buy the Book © 2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska Portions of this book originally appeared in Tin House and Howler. Images courtesy of United States Soccer Federation (Team America- Italy game program), the New York Cosmos (Cosmos yearbook), fifa and Roger Huyssen (fifa- unicef World All- Star Game program), Transatlantic Challenge Cup, ticket stubs, press passes (from author). All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Agovino, Michael J. The soccer diaries: an American’s thirty- year pursuit of the international game / Michael J. Agovino. pages cm isbn 978- 0- 8032- 4047- 6 (hardback: alk. paper)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5566- 1 (epub)— isbn 978-0-8032-5567-8 (mobi)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5565- 4 (pdf) 1. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally.