Research Paper - Nº1 - September 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey's

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey’s Kurdish Policy Ayşegül Aydin Cem Emrence turkey project policy paper Number 10 • December 2016 policy paper Number 10, December 2016 About CUSE The Center on the United States and Europe (CUSE) at Brookings fosters high-level U.S.-Europe- an dialogue on the changes in Europe and the global challenges that affect transatlantic relations. As an integral part of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, the Center offers independent research and recommendations for U.S. and European officials and policymakers, and it convenes seminars and public forums on policy-relevant issues. CUSE’s research program focuses on the transforma- tion of the European Union (EU); strategies for engaging the countries and regions beyond the frontiers of the EU including the Balkans, Caucasus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine; and broader European security issues such as the future of NATO and forging common strategies on energy security. The Center also houses specific programs on France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. About the Turkey Project Given Turkey’s geopolitical, historical and cultural significance, and the high stakes posed by the foreign policy and domestic issues it faces, Brookings launched the Turkey Project in 2004 to foster informed public consideration, high‐level private debate, and policy recommendations focusing on developments in Turkey. In this context, Brookings has collaborated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) to institute a U.S.-Turkey Forum at Brookings. The Forum organizes events in the form of conferences, sem- inars and workshops to discuss topics of relevance to U.S.-Turkish and transatlantic relations. -

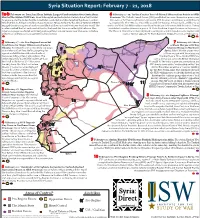

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

Of Iraq's Kirkuk

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 392 NOVEMBER 2017 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Misen en page et maquette : Ṣerefettin ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 392 November 2017 • ROJAVA: PREPARING MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE • TURKEY: THE REPRESSION EXPANDS TO LIBER- AL CIRCLES; THE VIOLENCE IS INCREASING • IRAQI KURDISTAN: UNCONSTITUTIONAL DEMANDS FROM BAGHDAD, ARABISATION OF KIRKUK RESTARTED ROJAVA: PREPARING MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE. broad the “World Day for beginning to return to Raqqa, liber- the 17th with a suicide attack on a Kobani” was celebrated ated on 17th October. Regarding checkpoint that caused at least 35 on 1st November largely Deir Ezzor, the SDF fighters from victims in the Northeast of Deir as a symbol of this Syrian the “Jezirah Storm” operation, Ezzor Province, between the hydro- A Kurdish town’s unremit- launched on 9th September, liberated carbon fields of Conoco and Jafra. It ting resistance to the attack 7 villages near the town and about was, nevertheless, not able to pre- launched by ISIS in 2014 with fifteen km from the Iraqi borders, vent the SDF from reaching the Iraqi Turkish connivance. -

Download the Publication

Viewpoints No. 99 Mission Impossible? Triangulating U.S.- Turkish Relations with Syria’s Kurds Amberin Zaman Public Policy Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Center; Columnist, Diken.com.tr and Al-Monitor Pulse of the Middle East April 2016 The United States is trying to address Turkish concerns over its alliance with a Syrian Kurdish militia against the Islamic State. Striking a balance between a key NATO ally and a non-state actor is growing more and more difficult. Middle East Program ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ On April 7 Syrian opposition rebels backed by airpower from the U.S.-led Coalition against the Islamic State (ISIS) declared that they had wrested Al Rai, a strategic hub on the Turkish border from the jihadists. They hailed their victory as the harbinger of a new era of rebel cooperation with the United States against ISIS in the 98-kilometer strip of territory bordering Turkey that remains under the jihadists’ control. Their euphoria proved short-lived: On April 11 it emerged that ISIS had regained control of Al Rai and the rest of the areas the rebels had conquered in the past week. Details of what happened remain sketchy because poor weather conditions marred visibility. But it was still enough for Coalition officials to describe the reversal as a “total collapse.” The Al Rai fiasco is more than just a battleground defeat against the jihadists. It’s a further example of how Turkey’s conflicting goals with Washington are hampering the campaign against ISIS. For more than 18 months the Coalition has been striving to uproot ISIS from the 98- kilometer chunk of the Syrian-Turkish border that is generically referred to the “Manbij Pocket” or the Marea-Jarabulus line. -

Implementing Stability in Iraq and Syria 3

Hoover Institution Working Group on Military History A HOOVER INSTITUTION ESSAY ON THE DEFEAT OF ISIS Implementing Stability in Iraq and Syria MAX BOOT Military History The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) first captured American attention in January 2014 when its militants burst out of Syria to seize the Iraqi city of Fallujah, which US soldiers and marines had fought so hard to free in 2004. Just a few days later ISIS captured the Syrian city of Raqqa, which became its capital. At this point President Obama was still deriding it as the “JV team,” hardly comparable to the varsity squad, al-Qaeda. It became harder to dismiss ISIS when in June 2014 it conquered Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, and proclaimed an Islamic State under its “caliph,” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. With ISIS executing American hostages, threatening to massacre Yazidis trapped on Mount Sinjar, and even threatening to invade the Kurdish enclave in northern Iraq, President Obama finally authorized air strikes against ISIS beginning in early August 2014. This was soon followed by the dispatch of American troops to Iraq and then to Syria to serve as advisers and support personnel to anti-ISIS forces. By the end of September 2016, there were more than five thousand US troops in Iraq and three hundred in Syria.1 At least those are the official figures; the Pentagon also sends an unknown number of personnel, numbering as many as a few thousand, to Iraq on temporary deployments that don’t count against the official troop number. The administration has also been cagey about what mission the troops are performing; although they are receiving combat pay and even firing artillery rounds at the enemy, there are said to be no “boots on the ground.” The administration is more eager to tout all of the bombs dropped on ISIS; the Defense Department informs us, with impressive exactitude, that “as of 4:59 p.m. -

1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During The

Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During the reporting period, the Turkish-led Operation Olive Branch offensive continued its advance into Afrin, the northwestern canton controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a US-backed, Kurdish- led organization). Elsewhere, pro-government forces continued their advance against opposition forces and ISIS fighters in the northern Hama/southern Aleppo countryside, further securing their control in the area. Following a significant uptick in attacks on both the opposition-controlled Idleb and Eastern Ghouta pockets, the UN humanitarian coordinator, Panos Moumtzis, called for an immediate one-month cessation of hostilities for the delivery of humanitarian aid. Lastly, a new opposition “operation room” has been formed in Idleb, with the stated goal of coordinating attacks against government forces. Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by February 7, with arrows indicating fronts of advance during the reporting period 1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary – February 1-7, 2018 Operation Olive Branch Operation Olive Branch forces took new territory, connecting previously isolated territories west of Raju and north of Balbal. Turkey-backed Operation Euphrates Shield forces also advanced northwest of A’zaz to take a mountaintop and village from the SDF. No gains have yet been made towards Tal Refaat along the southeastern front. There have been reports of abuses by advancing Turkish-backed, opposition Free Syrian Army (FSA) forces, including footage of Operation Olive Branch forces apparently mutilating the body of a deceased YPJ fighter (an all-female Kurdish unit within the SDF). Hundreds of US-trained YPG/SDF fighters from eastern SDF cantons arrived in Afrin this week, traveling through government-held territory to reinforce the SDF fighters on fronts against Olive Branch units. -

Women Rights in Rojava- English

Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 2 1- Women’s Political Role in the Autonomous Administration Project in Rojava ...................................... 3 1.1 Women’s Role in the Autonomous Administration ....................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Committees for Women ......................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 The Women’s Committee ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Women’s Associations - The “Kongreya Star” ........................................................................ 5 1.2 Women’s Representation in Political and Administrative Bodies: ................................................. 6 2. Empowering Women in the Military Field ........................................................................................... 11 2.1 The Representation of Women in the Army ................................................................................ 11 2.2 The People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) ................................. 12 2.2.1 The Women’s Protection Units- YPJ ..................................................................................... 12 2.2.2 The People’s Protection Units- YPG ..................................................................................... -

October 2014

www.rbs0.com/syria14.pdf 8 Nov 2014 Page 1 of 86 Syria & Iraq: October 2014 Copyright 2014 by Ronald B. Standler No copyright claimed for quotations. No copyright claimed for works of the U.S. Government. Table of Contents 1. Chemical Weapons in Syria Alleged Use of Chlorine Gas at Kafr Zeita on 11 April Alleged Use of Chlorine Gas in Iraq on 15 Sep 2. Syria United Nations Diverted from Syria death toll in Syria now over 193,000 (31 Oct) Rebels in Syria, including U.S. Military aid Recognition that Assad is Winning the Civil War New U.N. Negotiator for Syria U.N. Security Council Resolutions 2139 and 2165 (24 Sep, 23 Oct) Henning beheaded 3. Iraq Iraq death toll atrocities in Iraq ISIL bombings in Iraq ISIL executions in Iraq Islamic public relations problem No Criminal Prosecution of Cowardly Iraqi Army Officers Iraqi Parliament meets ministers approved (18 Oct) 4. Daily News about Syria & Iraq (including press briefings & press conferences, speeches) Turkey Parliament votes to fight ISIL (2 Oct); Turkey vs. Kurds more Daily News (3-7 Oct) siege of Kobani suggestions that airstrikes ineffective (begins 7 Oct) Anbar province to fall? (begins 9 Oct) more Daily News (9-22 Oct) 5. U.S. Airstrikes in Iraq & Syria, U.S. Military Policy 39 airstrikes near Kobani during 14-15 Oct airdrop in Kobani on 19 Oct www.rbs0.com/syria14.pdf 8 Nov 2014 Page 2 of 86 6. Conclusions Foreword I have posted an annotated list of my previous eleven essays on Syria. That webpage also includes links to historical documents on the Syrian civil war and a table of dates of removals of chemical weapons from Syria. -

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo, Azaz (as of 1 June 2016) Summary An estimated 16,150 individuals in total have been displaced by fighting since 27 May in the northern Aleppo countryside, with most joining settlements adjacent to the Bab Al Salam border crossing point, Azaz town, Afrin and Yazibag. Kurdish authorities in Afrin Canton have allowed civilians unimpeded access into the canton from roads adjacent to Azaz and Mare’ since 29 May in response to ongoing displacement near hostilities between ISIL and NSAGs. Some 9,000 individuals have been afforded safe passage to leave Mare’ and Sheikh Issa towns after they were trapped by fighting on 27 May; however, an estimated 5,000 civilians remain inside despite close proximity to frontlines. Humanitarian organisations continue to limit staff movement in the Azaz area for safety reasons, and some remain in hibernation. Limited, cautious humanitarian service delivery has started by some in areas of high IDP concentration. The map below illustrates recent conflict lines and the direction of movement of IDPs: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Coordination Saves Lives | www.unocha.org Turkey | Syria: Azaz, Flash Update No.2 Access Overview Despite a recent decline in hostilities since May 27, intermittent clashes continue between NSAGs and ISIL militants on the outskirts of Kafr Kalbien, Kafr Shush, Baraghideh, and Mare’ towns. A number of counter offensives have been coordinated by NSAGs operating in the Azaz sub district, hindering further advancements by ISIL militants towards Azaz town. As of 30 May, following the recent decline in escalations between warring parties, access has increased for civilians wanting to leave Azaz and Mare’ into areas throughout Afrin canton. -

The West's Darling in Syria

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Comments The West’s Darling in Syria WP Seeking Support, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party Brandishes an Anti-Jihadist Image Khaled Yacoub Oweis S US bombings in 2015 repulsed Islamic State attacks on cities in mostly Kurdish self- rule regions called cantons in northern Syria. The three cantons, which border Turkey, are dominated by the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD). The party is linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a former client of the Syrian regime and considered a “terrorist” group by the United States, the European Union, and Turkey. At the risk of deepening an Arab Sunni backlash that has fanned radicalization, Washington is set ever more on the prospect of the PYD retaking mostly Arab territory captured by the Islamic State. In line with German reluctance to arm warring sides, Berlin has refrained from giving military aid to the PYD, which is accused of carrying out war crimes. Still, an international effort to rebuild the cantons tied to breaking the PYD’s monopoly on them could help stabilize the area – even more so if Turkey could be brought on board. The Kurds have scored some of the biggest PYD is not calling for outright secession. Its territorial gains in Syria since the outbreak declaration of self-rule and accompanying of revolt against Assad family rule in 2011. “social contract” mix Marxist jargon and a Cooperation with the Assad regime and vague form of popular democracy. The docu- backing from the United States against the ments also emphasize rights for women so-called Islamic State have strengthened and minorities. -

Operation Inherent Resolve Report/Operation Pacific Eagle-Philippines, Report to the United States Congress, January 1, 2018-Mar

LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL I REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE OPERATION PACIFIC EAGLE–PHILIPPINES JANUARY 1, 2018‒MARCH 31, 2018 LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL MISSION The Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations coordinates among the Inspectors General specified under the law to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight over all aspects of the contingency operation. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of all programs and operations of the Federal Government in support of the contingency operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, and investigations. • Promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness and prevent, detect, and deter fraud, waste, and abuse. • Perform analyses to ascertain the accuracy of information provided by Federal agencies relating to obligations and expenditures, costs of programs and projects, accountability of funds, and the award and execution of major contracts, grants, and agreements. • Report quarterly and biannually to the Congress and the public on the contingency operation and activities of the Lead Inspector General. (Pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978) FOREWORD We are pleased to submit the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) quarterly report to the U.S. Congress on Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) and Operation Pacific Eagle- Philippines (OPE-P). This is our 13th quarterly report on OIR and 2nd quarterly report on OPE-P, discharging our individual and collective agency oversight responsibilities pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978. The United States launched OIR at the end of 2014 to militarily defeat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in the Combined Joint Area of Operations in order to enable whole-of-governmental actions to increase regional stability.