LH Moretsi Orcid.Org 0000-0002-3095-1777

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72 was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. ". there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."2 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. As with some of the added and updated material in the historical books, the Holy Spirit evidently led editors to add material that the original writer did not include. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Psalm 113-114 Psalms Praising God for His Deliverance Psalms 113-118

Finding Yourself in the Psalms Psalm 113-114 Psalms Praising God for His Deliverance Psalms 113-118 - The HALLEL. Recited during PASSOVER, TABERNACLES, PENTECOST 113-114 Sung at the Passover Meal, after the 2nd CUP 113 - 3 Stanzas, 3 verses each. - Trinity - Praise and Deliverance 114 - Deliverance from Egypt I. Praise Him EVERYWHERE. 113:1-3 II. Praise Him EVERYONE. 113:4-6 III. The Deliverer of the NEEDY. 113:7-9 A. 113:7. “Dust” (Psalm 103:14) "for he knows how we are formed, he remembers that we are dust." B. “When you’re as low as you can get, God is there waiting to deliver you.” C. (Psalm 40:1-3) "I waited patiently for the Lord; he turned to me and heard my cry. He lifted me out of the slimy pit, out of the mud and mire; he set my feet on a rock and gave me a firm place to stand. He put a new song in my mouth, a hymn of praise to our God. Many will see and fear and put their trust in the Lord." D. The Songs of HANNAH and MARY. 113:9 1. (1 Samuel 2:8) "He raises the poor from the dust and lifts the needy from the ash heap; he seats them with princes and has them inherit a throne of honor. “For the foundations of the earth are the Lord’s; upon them he has set the world." 2. (Luke 1:52) "He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble." 3. -

Psalm 75 — God Will Judge

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2006 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 75 — God Will Judge 1.0 Introducing Psalm 75 y Psalms 50 and 73–83 attribute their composition to Asaph. 9 There could be more than one Asaph. 9 “Asaph” might sometimes refer to a descendant of Asaph (cp. 2 Chron 35:15). y Psalm 75 shares themes and phraseology with “Hannah’s Song” (1 Samuel 2:1-10) and Mary’s “Magnificat” (Luke 1:46-55). y Placement of Psalm 75 following 74 highlights common emphases: 9 The psalmist prays for God to act (74:22-23) and He does (75:7, 10). 9 God is King (74:12) and God is Judge (75:2, 7). 9 Question of “How long?” (74:10) will be answered at “an appointed time” (75:2). 9 Both “meeting places” (74:8) and “appointed time” (75:2) translate the same Hebrew word (74:8 is the plural). 9 “Your name” occurs in both psalms (74:7, 10, 18, 21; 75:1). 2.0 Reading Psalm 75 (NAU) 75:1 A Psalm of Asaph, a Song. We give thanks to You, O God, we give thanks, For Your name is near; Men declare Your wondrous works. 75:2 “When I select an appointed time, It is I who judge with equity. 75:3 “The earth and all who dwell in it melt; It is I who have firmly set its pillars. Selah. Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs 2 Barrick, Placerita Baptist Church 2006 75:4 “I said to the boastful, ‘Do not boast,’ And to the wicked, ‘Do not lift up the horn; 75:5 “‘Do not lift up your horn on high, Do not speak with insolent pride.’” 75:6 For not from the east, nor from the west, Nor from the desert comes exaltation; 75:7 But God is the Judge; He puts down one and exalts another. -

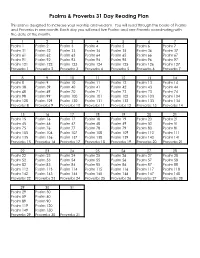

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Editorial: “Be Exalted, O God, Above the Heavens!” (Psalm 108:6) - Studies in the Book of Psalms and Its Reception Presented to Phil J

288 Prinsloo and Weber, “Editorial,” OTE 32/2 (2019): 288-301 Editorial: “Be exalted, o God, above the Heavens!” (Psalm 108:6) - Studies in the Book of Psalms and its reception Presented to Phil J. Botha on his 65th birthday GERT T. M. PRINSLOO AND BEAT WEBER (UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA) Philippus (Phil) Jacobus Botha Prinsloo and Weber, “Editorial,” OTE 32/2 (2019): 288-301 289 A new psalm had to be composed for new circumstances. It made use of a well-known oracle of God, but in a new political, social, religious, and/or historical context, that oracle had a new message. In a context of praise, it opened a perspective to the future. It emphasized in a new way that God had to bring about the new dispensation, and that he would. They gave the faithful a new historical and cosmological perspective.1 This issue of Old Testament Essays is dedicated to Philippus (Phil) Jacobus Botha on the occasion of his 65th birthday and subsequent retirement from the Department of Ancient and Modern Languages and Cultures at the University of Pretoria. In a publication on Psalm 108 referred to above, Phil Botha defined the poem – a composition based upon Pss 57:8-12 and 60:7-14 – as a new psalm that “had to be composed for new circumstances”. It is a great honour for everyone involved in this project to dedicate this issue to our esteemed colleague and friend as he reaches the stage in his life cycle where he inevitably enters new circumstances. It is our sincere wish that the diverse and wide-ranging contributions in this volume will aid him in the process of composing a new life- psalm based upon the many enriching moments he experienced and the many inspirational contributions he made during his long and fruitful academic career. -

Outline of Psalms

Outline of Psalms We hope this overview and outline of Psalms will assist you as you study God’s Word. General Background: The Book of Psalms is a book to be sung. It is Israel’s and the Church’s songbook. We have seven named authors. David wrote 77 of the Psalms (2 [Acts 4:25], 3-9, 11-32, 34-41, 51-65, 68-70, 86, 95 [Hebrews 4:7], 96 [1 Chronicles 16:23-33], 101, 103, 105:1-15 [1 Chronicles 16:7-22], 108-110, 122, 124, 131, 133, 138-145); Asaph wrote 12 (50, 73-83); the sons of Korah wrote nine (42, 44-45, 47-49, 84-84, 87); Solomon wrote two (72, 127); Moses wrote one (90); Heman wrote one (88); and Ethan wrote one (89). We do not know the authors of the other 47 Psalms. The Psalms span from Moses in the late fifteenth century B.C. until the late sixth century B.C. (126, 137), covering the entire national period of Israel in the Old Testament. The Book of Psalms is about God. God is mentioned by name in the Psalms 1,220 times, and appears in each Psalm. “Yahweh” (LORD) is found in 132 of the Psalms and “Elohim” (God) is found in 109. Psalm 68 contains the name of God 42 times; Psalm 133 only once. Yet, merely counting the mentions of His name does not tell the full story. Pronouns referencing Him abound throughout the Psalms. For instance, in Psalm 119, the name of God is found 24 times, but a personal pronoun referring to God is found 347 times. -

Titles of Psalms 6,12

British Bible School – Online Classes: 14th September 2020 – 30th November 2020 THE PSALMS THE TITLES OF THE PSALMS 1. The superscriptions or titles found to many of the Psalms (116 have titles) are not thought to be part of the original text but do reflect an ancient and reliable description of the setting or occasion of writing. The Hebrew texts include them as part of the text of the Psalm. Some English versions, such as the New English Bible and the Good News Bible do not include them at all. Some of the terms used in some of the titles are obscure and their meaning cannot be ascertained for certain. Often the translators have simply transliterated the Hebrew word into English rather than try to offer an English equivalent. These titles reflect: i) The style or character of the Psalm. ii) The musical setting. iii) The occasion for use. iv) Authorship. v) The occasion of writing. 2. Titles that reflect the style or character of the Psalm i) MIZMOR – Translated as “Psalm” – occurs in 57 titles, e.g. Psalm 98. It is often followed by the name of the author, e.g. Psalm 101. It means ‘a song with instrumental accompaniment.’ ii) SHIR – Translated as “Song” – occurs in 30 titles, e.g. Psalm 108. It is a general term for a song. iii) MASKIL – occurs in 13 titles, e.g. Psalm 32; 42. The meaning of the term is uncertain. It may mean a teaching psalm or a meditation, or a psalm of understanding. iv) MIKHTAM – occurs in 6 titles, e.g. -

Studies in Biblical Poetry the Collected Notes of C.A

Studies in Biblical Poetry The Collected Notes of C.A. LaRue 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION SECTION ONE: PSALMS SECTION TWO: LAMENTATIONS SECTION THREE: SONG OF SONGS SECTION FOUR: JOB SECTION FIVE: PROVERBS SECTION SIX: ECCLESIATES SECTION SEVEN: THE PROPHETS AND OTHER WRITINGS SECTION EIGHT: THE NEW TESTAMENT 2 INTRODUCTION: *from myjewishlearning.com The Poetic Writings Approximately one-third of the Old testament is written in poetry. The three main divisions-- the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings - contain poetry in successively greater amounts. Only seven Old Testament books - Leviticus, Ruth, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, Haggai, and Malachi - appear to have no poetic lines. Several books in the OT are written either totally (Psalms, Lamentations and Song of Songs) or predominantly in poetry (Job, Proverbs and Ecclesiastes). Moreover, many parts of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the Minor Prophets also contain poetic writings. While each of these Old Testament books has its own unique tone and style, in general, the poetry they contain can be grouped into 5 basic types: Worship: •Hymns praising God. (Psalm 8) •Psalms of thanksgiving for deliverance. (Psalms 30,124) •Psalms of supplication, voicing complaints and requests. (Psalms 44,64) Teaching: •Proverbs (Ecclesiastes10:18), •Riddles (Proverbs 30:4), •Wise advice (Proverbs 4), •Narrative poems about traditions (Psalms 78, 132), •Narrative poems with a moral (Proverbs 7), •Hymns praising wisdom (Job 28), •Wisdom on the futility and fragility of human life (Ecclesiastes 1:4-9). Prophecy: •Prophecies of reproof and warning (Isaiah 34), •Prophecies of consolation (Isaiah 35). Weddings: •Processionals (Song 3:9-11), 3 •Songs for the bride's preparation (Song 4:1-7), •Epithalamiums outside the wedding chamber (Psalm 127), •Dawn songs greeting newlyweds after the wedding night (Song 6:9-10), •Blessings (Psalm 128). -

Psalms 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time, the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title, resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72, or 71, was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently, the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. 1See Gleason L. Archer Jr., A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, p. 439. Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. Constable www.soniclight.com 2 Dr. Constable's Notes on Psalms 2021 Edition "… there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."1 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. -

The Book of Jonah

The Book of Jonah Dr. Tim Mackie Contents Unit 1: Our Assumptions About the Story of Jonah 4 Session 1: Relearning the Story of Jonah 4 Session 2: How to Read a Text Like the Hebrew Bible 5 Session 3: Old Testament 101 According to Jesus (Q&R) 6 Session 4: The Main Message of the Hebrew Scriptures 7 Session 5: How to Read the Bible (Q&R) 8 Unit 2: The Literary Context of Jonah 9 Session 6: Introduction to the TaNaK Order 9 Session 7: Reflection on Jonah and the TaNaK Order (Q&R) 11 Session 8: The “Seams” of the TaNaK 12 Session 9: The Biblical Pattern (Q&R) 13 Unit 3: Hyperlinks and Patterns Between Jonah and the Rest of Scripture 14 Session 10: Hyperlinks in the Text 14 Session 11: Nineveh (Q&R) 15 Session 12: Biblical Patterns the Author Assumes You Know 16 Session 13: God’s Character Summarized 17 Session 14: God’s Character (Q&R) 18 Unit 4: Links Between Literary Units 19 Session 15: Noticing Repeated Words 19 Session 16: How to Read an Ancient Text 24 Session 17: Repeated Words and Implications for Literary Design 28 Session 18: Hyperlinks in the Hebrew Bible 29 Session 19: Seeing the Hyperlinks (Q&R) 34 Session 20: Hyperlinks in Star Wars and in Jonah 36 Session 21: Characterization and Setting in Biblical Narrative 37 CLASSROOM NOTES: THE BOOK OF JONAH Unit 5: Jonah 1 38 Session 22: Why Does Jonah Flee to Tarshish? 38 Session 23: Identifying Repeated Words 46 Session 24: The Symmetry of the Ship Scene 47 Session 25: Jonah’s Motives (Q&R) 48 Session 26: Jonah’s Upside-Down Character 49 Session 27: Relationships Between Jonah and -

Contents Overview of Readings

Through the Scriptures: Year 2 Contents Overview of Readings ...................................................................................................................... 3 Week 53 ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Week 54 ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Week 55 ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Week 56 ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Week 57 ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Week 58 ......................................................................................................................................... 17 Week 59 ......................................................................................................................................... 19 Week 60 ......................................................................................................................................... 21 Week 61 ......................................................................................................................................... 24 Week 62 ........................................................................................................................................