Empower Women: Facing the Challenge of Tobacco Use in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2018 GSTHR 1 2 GSTHR

NO FIRE, NO SMOKE: THE GLOBAL STATE OF TOBACCO HARM REDUCTION 2018 GSTHR 1 2 GSTHR No Fire, No Smoke: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2018 Written and edited by Harry Shapiro Report and website production coordination: Grzegorz Krol The full report (pdf) is available at www.gsthr.org Country profiles are available atwww.gsthr.org To obtain a hard copy of the full report go to www.gsthr.org/contact The Executive Summary is available in various languages at www.gsthr.org/translations Copy editing and proofing: Tom Burgess, Ruth Goldsmith and Joe Stimson Project management: Gerry Stimson and Paddy Costall Report design and layout: Urszula Biskupska Website design & coding: Filip Woźniak, Vlad Radchenko Print: WEDA sc Knowledge-Action-Change, 8 Northumberland Avenue, London, WC2N 5BY © Knowledge-Action-Change 2018 Citation: No Fire, No Smoke: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2018 (2018). London: Knowledge-Action-Change. NO FIRE, NO SMOKE: THE GLOBAL STATE OF TOBACCO HARM REDUCTION 2018 GSTHR 3 Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary: No Fire, No Smoke: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2018 5 Scope and terminology 8 Website 8 Updating 8 Data sources and limitations 8 Forewords: 10 Nancy Sutthoff 10 David Sweanor 10 Martin Jarvis 11 Key acronyms and abbreviations 12 Chapter 1: Introduction: tobacco harm reduction 13 Chapter 2: The continuing global epidemic of cigarette smoking 17 Chapter 3: Safer nicotine products: a global picture 22 Chapter 4: Consumers of safer nicotine products 38 Chapter 5: Safer nicotine products -

Tobacco Securitization

Memorandum Office of Jenine Windeshausen Treasurer-Tax Collector To: The Board of Supervisors From: Jenine Windeshausen, Treasurer-Tax Collector Date: October 27, 2020 Subject: Tobacco Securitization Action Requested a) Adopt a resolution consenting to the issuance and sale by the California County Tobacco Securitization Agency not to exceed $67,000,000 initial principal amount of tobacco settlement bonds (Gold Country Settlement Funding Corporation) Series 2020 Bonds in one or more series and other related matters; authorizing the execution and delivery by the county of a certificate of the county; and authorizing the execution and delivery of and approval of other related documents and actions in connection therewith. b) Direct that eligible proceeds from the Series 2020 Bonds be expended on infrastructure improvements at the Placer County Government Center, construction of the Health and Human Services Building and other Board approved capital facilities projects. Background October 6, 2020 Board of Supervisors Meeting Summary. Your Board received an update regarding the County’s prior tobacco securitizations and information on the potential to refund the Series 2006 Bonds to receive additional proceeds for capital projects. Based on that update, the Board requested the Treasurer to return to the Board on October 27, 2020 with a resolution approving documents and other matters to proceed with refunding the Series 2006 Bonds. In summary from the October 6, 2020 meeting, the County receives annual payments in perpetuity from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA). The MSA payments are derived from a percentage of cigarette sales. Placer County issued bonds in 2002 and 2006 to securitize a share of its MSA payments. -

Bases Loaded Beyond E-Cigs and Vapor Devices, New Tobacco Technologies Are Stepping up to by Renée Covino the Plate with Power

JTI Debuts a New Design for Wave MAY/JUNE 2015 VOLUME 18 n NUMBER 3 The Tobacco Innovation Game: BASES LOADED BEYOND e-cigs and vapor devices, NEW tobacco technologies are STEPPING UP to By Renée Covino the plate with POWER. Will reduced-harm products and OTHER innovations change up the COMPETITIVE FIELD? 2015 Vapor Expo Preview The Dark Side of Taxation Uhle Tobacco Company’s Journey PUBLISHER’S LETTER BY ED O’CONNOR Father’s Day 2015… Now 115 Years Old Father’s Day turned 100 years old on June 20, 2010. Sono- So we’ve done the next best thing. Enjoy “Unforbidden ra Smart Dodd, often referred to as the “Mother of Father’s Fruit,” Renee Covino’s article on Cuban cigars appearing in Day,” was 16 years old when her mother died in 1898, the March/April issue of TBI (p. 30) with comments by Dick leaving her father, William Jackson Smart, to raise Sonora Dimeola, a premium cigar expert and long-time friend of and her five younger brothers on a remote farm in eastern the cigar industry, Victor Vitale, Marshall Gray and other ci- Washington. In 1909, Sonora heard a Mother’s Day church gar aficionados. Don’t have a hard copy? Your cigar article sermon inspiring her to propose that fathers receive equal is available to you on tobonline.com. recognition, lending credence to the old saying, “Behind For those of us excited about the dynamic growth of the every good man there’s a good woman.” electronic nicotine (c-cig and VTM) markets, be sure to With the assistance of her pastor, the Spokane, Wash- check out this issue’s Electric Alley column (p. -

Imperial Tobacco Finance

Prospectus Imperial Tobacco Finance PLC A9.4.1.1 (Incorporated with limited liability in England and Wales with registered number 03214426) A9.4.1.2 Imperial Tobacco Finance France SAS (A société par actions simplifiée incorporated in France) €15,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme Irrevocably and unconditionally guaranteed by Imperial Tobacco Group PLC A9.4.1.1 (Incorporated with limited liability in England and Wales with registered number 03236483) A9.4.1.2 This Prospectus amends, restates and supersedes the offering circular dated 21st February 2014. Any Notes issued after the date hereof under the Debt Issuance Programme described in this Prospectus (the “Programme”) are issued subject to the provisions set out herein. This Prospectus will not be effective in respect of any Notes issued under the Programme prior to the date hereof. Under the Programme, Imperial Tobacco Finance PLC (“Imperial Finance” or an “Issuer”) and Imperial Tobacco Finance France SAS A6.1 (“Imperial Finance France” or an “Issuer” and together with Imperial Finance “the Issuers”), subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, may from time to time issue debt securities (the “Notes”) guaranteed by Imperial Tobacco Group PLC (“Imperial Tobacco” or the “Guarantor”) and Imperial Tobacco Limited (“ITL”). Please see the Trust Deed dated 6th February 2015 (the “Trust Deed”) which is available for viewing by Noteholders as described on page 124 for further details about the Imperial Tobacco guarantee and page 98 for further details regarding the ITL guarantee. The aggregate nominal amount of Notes outstanding will not at any time exceed €15,000,000,000 (or the equivalent in other currencies). -

E-Cigarettes 003292 Blu Ecigs®

July 12, 2012 TO: Wholesalers reporting Shipment Data to MSAi for blu ecigs SUBJECT: 2012 blu ecigs DATA REPORTING PROGRAMMING DETAILS Enclosed is a copy of the 2012 blu ecigs Data Reporting Programming Details document which includes Data reporting instructions for reporting Electronic Cigarettes to MSAi for blu ecigs using the Multi-CatTM All Tobacco Format. This document is being sent to you in response to your recent enrollment with blu ecigs to report shipment Data for electronic cigarettes. These instructions outline standard requirements for reporting Electronic Cigarette products to blu ecigs, which includes disposables, refill cartridges and kits. The attached document reflects the assignment of a new MSAi Category Code that should be used for reporting Data for Electronic Cigarettes in the Multi-CatTM All Tobacco Format. E-Cigarettes 003292 All Wholesalers reporting Shipment Data to MSAi for blu ecigs must ensure that their systems reflect the required product descriptions to ensure that weekly sales of blu ecigs products to your customers are correctly reported to the Distributor Support Center. Contact the Distributor Support Center at (1-877-544-4429) for questions pertaining to reporting Electronic Cigarettes under the MULTICATTM format. blu ecigs® blu ecigs is a registered trademark of Lorillard Technologies, Inc. blu ecigs Data Reporting Program 2012 MultiCatTM All Tobacco Data Programming Details MSAi Copyright©2012 Updated on 6-28-12 blu ecigs Data Reporting Requirements – V. 1.0 (Effective 7/01/12) blu ecigs DATA REPORTING REQUIREMENTS Data: • All Data which includes shipments to retail, returns, and inventory must be reported in selling units and submitted in the following reporting format outlined in this document: MULTICATTM All Tobacco Format Wholesalers opting to utilize the optional MULTICATTM Format to satisfy blu ecigs reporting program requirements must agree to release all sales Data to blu ecigs. -

Tobacco Use Behaviors for Swedish Snus and US Smokeless Tobacco

Tobacco Use Behaviors for Swedish Snus and US Smokeless Tobacco Prepared for: Swedish Match, Stockholm, Sweden and Swedish Match North America, Richmond, Virginia Prepared by: ENVIRON International Corporation Arlington, Virginia Date: May 2013 Project Number: 2418132C Snus and US Smokeless Tobacco Contents Page Executive Summary 1 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Background 6 1.2 Literature search and methods 8 2 Temporal, Geographic and Demographic Patterns of Smokeless Tobacco Use. 10 2.1 Scandinavia 10 2.1.1 Current and Historical Temporal Trends of Swedish Snus 10 2.1.2 Geographic variations in snus use 12 2.1.3 Age and gender 12 2.1.4 Socioeconomic and occupational variations in snus 14 2.1.5 Other individual level characteristics related to snus 15 2.1.6 Exposure estimates: frequency, amount and duration of snus 15 2.2 United States 17 2.2.1 Temporal trends 18 2.2.2 Geographic variations in smokeless tobacco use 19 2.2.3 Age and gender 20 2.2.4 Race/ethnicity 21 2.2.5 Socioeconomic and occupational variations in smokeless tobacco use 22 2.2.6 Other individual level characteristics related to smokeless tobacco use 23 2.2.7 Exposure estimates: frequency, amount and duration of smokeless tobacco use 23 2.3 Summary and Conclusions 23 3 Relationship of Smokeless Tobacco to Smoking 25 3.1 Population-level transitioning between tobacco products 26 3.1.1 Scandinavia 26 3.1.2 United States 27 3.2 Individual-level transitioning between tobacco products: Gateway and transitioning from smokeless tobacco to cigarettes 27 3.2.1 Scandinavia 28 3.2.2 United States 31 3.3 Transitioning from cigarettes to smokeless tobacco and smoking cessation 35 3.3.1 Scandinavia 36 3.3.2 United States 41 3.4 Snus/Smokeless Tobacco Initiation 45 3.4.1 Scandinavia 45 3.4.2 United States 46 3.5 Dual Use 47 3.5.1 Scandinavia 47 3.5.2 United States 52 4 Summary and Conclusions 57 Contents i ENVIRON Snus and US Smokeless Tobacco 5 References 60 List of Tables Table 1: Recent Patterns of Snus Use in Sweden (Digard et al. -

Cigarette Price List Effective 02Nd December 2019

Cigarette Price List Effective 02nd December 2019 Price Name Price Name €18.20 B&H Maxi Box 28’s €13.20 Superkings Black €18.20 Silk Cut Blue 28’s €13.20 Superkings Blue €18.20 Silk Cut Purple 28’s €13.20 Superkings Green Menthol €17.00 Marlboro Gold KS Big Box 28s €13.20 Pall Mall 24’s Big Box €16.65 Major 25’s €13.20 JPS Red 24’s €16.40 John Player Blue Big Box 27’s €13.20 JPS Blue 24’s €16.00 Mayfair Superking Original 27’s €13.00 Silk Cut Choice Super Line 20s €16.00 Mayfair Original 27’s €13.00 John Player Blue €16.00 Pall Mall Red 30’s €13.00 John Player Bright Blue €16.00 Pall Mall Blue 30’s €13.00 John Player Blue 100’s €16.00 JPS Blue 29’s €13.00 Lambert & Butler Silver €15.20 Silk Cut Blue 23’s €12.70 B&H Silver 20’s €15.20 Silk Cut Purple 23’s €12.70 B&H Select €15.20 B&H Gold 23’s €12.70 B&H Select 100’s €14.80 John Player Blue Big Box 24’s €12.70 Camel Filters €14.30 Carroll’s Number 1 23 Pack €12.70 Camel Blue €14.20 Mayfair Original 24’s €12.30 Vogue Green €13.70 Players Navy Cut €12.30 Vogue Blue Capsule €13.70 Regal €11.80 Mayfair Double Capsule €13.70 Rothmans €11.80 John Player Blue Compact €13.70 Consulate €11.80 Mayfair Original €13.70 Dunhill International €11.80 Pall Mall Red €13.50 B&H Gold 100’s 20s €11.80 Pall Mall Blue €13.50 Carroll’s No.1 €11.80 Pall Mall Red 100’s €13.50 B&H K.S. -

Volume 34, July 2015

In this issue: VOLUME 34 July 2015 Minneapolis Adopts Restrictions on Flavored Tobacco Products RJ Reynolds and Lorillard Merge Direct Mailing Project Updates TOBACCO MARKETING Reducing Youth Exposure to Tobacco Advertising and Promotion Minneapolis Adopts Restrictions on Flavored UPDATE Tobacco Products By BETSY BROCK The Minneapolis City Council voted unanimously on July 10 to restrict the sale of flavored tobacco products other than menthol to adult-only tobacco shops. The Council also increased the price of cigars to $2.60 apiece. Several other cities in Minnesota, including Maplewood, Bloomington, Saint Paul, and Brooklyn Center, have adopted policies that regulate the price of cheap cigars. However, no other Minnesota cities have restricted the sale of flavored tobacco products. Nationally, New York City and Providence, RI, have similar policies in place that served as a model for the Minneapolis ordinance. The new policy means that only about 15 of the city’s 400-plus tobacco vendors will be allowed to sell candy-flavored tobacco the Minneapolis Youth Congress and the Breathe Free North products. In order to sell these products, the stores must derive at program at NorthPoint Health & Wellness, who said these products least 90 percent of their revenue from tobacco and be adult-only at are appealing to young people. all times. Council Members Cam Gordon (Ward 2) and Blong Yang (Ward 5) “We heard loud and clear from Minneapolis youth that flavored co-authored the ordinance in response to an outcry from youth from tobacco products are what most kids use when they start smoking,” Council Member Cam Gordon said. -

4 Marketing Tactics E-Cigarette Companies Use to Target Youth

NEWS 4 marketing tactics e-cigarette companies use to target youth rom introducing appealing avors to offering college scholarships, manufacturers and sellers of e-cigarettes aggressively f target young people. There are few federal restrictions on e-cigarette marketing, allowing companies to promote their products through traditional outlets — such as TV and radio — despite a ban in 1971 on cigarette advertising on both outlets to reduce cigarette marketing to children. E-cigarette companies also take advantage of other marketing outlets, including the internet, retail environments and recreational venues and events. Youth and young adults are widely exposed to e-cigarette marketing and have high awareness of e-cigarettes, which are the most popular tobacco product among youth. By 2016, nearly 4 out of 5 middle and high school students, or more than 20 million youth, saw at least one e-cigarette advertisement. Here are four ways e-cigarette companies market their products to target young people. 1. Offering scholarships Several e-cigarette companies are offering scholarships, ranging from $250 to $5,000, that involve asking students to write essays on topics like whether vaping could have potential benets, according to the Associated Press. For example, one company asks applicants to write about whether e-cigarettes minimize smoking’s negative effects. E-cigarette manufacturers often say that their products are intended for adults who want to quit smoking; however, the AP reports that, “although some of the scholarships are limited to students 18 and older — the nation’s legal age to buy vaping products — many are open to younger teens or have no age limit.” “Most of these kids are not smokers,” said Robin Koval, CEO and president of Truth Initiative®, in the AP story. -

TNCO Levels and Ratio's

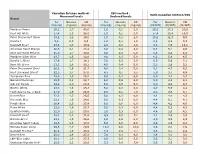

Canadian Intense method - ISO method - Ratio Canadian Intense/ISO Measured levels Declared levels Brand Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) Marlboro Prime 26,1 1,7 40,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 26,1 17,2 20,0 Kent HD White 17,4 1,3 28,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 17,4 13,4 14,0 Peter Stuyvesant Silver 15,2 1,2 19,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 15,2 12,3 9,5 Karelia I 9,6 0,9 9,3 1,0 0,1 1,0 9,6 8,6 9,3 Davidoff Blue* 23,6 1,7 30,9 2,9 0,2 2,6 8,3 7,0 12,1 American Spirit Orange 20,5 2,1 18,4 3,0 0,4 4,0 6,8 5,1 4,6 Kent Surround Menthol 25,0 1,7 30,8 4,0 0,4 5,0 6,3 4,3 6,2 Marlboro Silver Blue 24,7 1,5 32,6 4,0 0,3 5,0 6,2 5,0 6,5 Karelia L (Blue) 17,6 1,7 14,1 3,0 0,3 2,0 5,9 5,6 7,1 Kent HD Silver 21,1 1,6 26,2 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,3 3,9 5,2 Peter Stuyvesant Blue* 20,2 1,6 21,7 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,1 4,7 4,3 Kent Surround Silver* 22,5 1,7 27,0 4,5 0,5 5,5 5,0 3,7 4,9 Templeton Blue 25,0 1,8 26,2 5,0 0,4 6,0 5,0 4,4 4,4 Belinda Filterkings 29,9 2,2 24,7 6,0 0,5 6,0 5,0 4,3 4,1 Silk Cut Purple 24,9 2,0 23,4 5,0 0,5 5,0 5,0 4,0 4,7 Boston White 23,3 1,6 25,3 5,0 0,3 6,0 4,7 5,5 4,2 Mark Adams No. -

Swedish Tobacco Control-20Sid.Indd

Swedish Tobacco Control Progress & Challenge – both are greater than ever 2006 CONTENTS The Minister’s View The Voice of NGOs Snus is Harmful A Focus on Youth 1 June 2005 – Smoke-free Sweden Innovative Tobacco Cessation The Cost-Effective Quitline International Challenges Margaretha – Luther Terry Award Winner Meet the Swedish Network Photo: Åsa Till Swedish Beware of the Trojan horse… MORGAN JOHANSSON, SWEDEN’S MINISTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH: “The statistics on our smoking behaviours in Sweden are looking better and better every year, and I “We will be following believe that the new smoking ban is contributing to the continued decline.” Morgan Johansson, Minister of Public Health developments closely” Photo: Pawel Flato » Public Health Goals for the year 2014 “The ban on smoking in dining and drinking establishments that went into risks of smoking are much greater,” tobacco activity in their public health effect on 1 June 2005 is probably one of our most popular reforms,” says says Mr. Johansson. “However, there programmes. Reducing tobacco use is one of the primary are also health risks with snus and it is “We will be following develop- Morgan Johansson, Sweden’s Minister of Public Health, when he summarizes goals for public health set by the Swedish » best to stop using tobacco entirely. ments closely to make sure that there Parliament. It includes the following interim the current state of tobacco prevention in Sweden. “We are also striving to bring about are no cutbacks in that regard,” says targets: a reduction in the use of snus. For that Mr. Johansson. “In addition, the state purpose, it is necessary to provide in- must also provide fairly substantial • A tobacco-free start in life, effective by He states that, after nearly one year formation in the schools and other long-term resources for the work of the year 2014. -

Predictors of Smoking Cessation a Longitudinal Study in a Large Cohort

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Landspítali University Hospital Research Archive Respiratory Medicine 132 (2017) 164–169 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Respiratory Medicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rmed Predictors of smoking cessation: A longitudinal study in a large cohort of T smokers ∗ Mathias Holma, , Linus Schiölera, Eva Anderssona, Bertil Forsbergb, Thorarinn Gislasonc,d, Christer Jansone, Rain Jogif, Vivi Schlünsseng,h, Cecilie Svanesi,j, Kjell Toréna,k a Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden b Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Division of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Umea University, Umea, Sweden c Medical Faculty, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland d Department of Respiratory Medicine and Sleep, Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland e Department of Medical Sciences: Respiratory Medicine and Allergology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden f Lung Clinic, Tartu University Hospital, Tartu, Estonia g Department of Public Health, Section for Environment, Occupation and Health, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark h National Research Centre for the Working Environment, Copenhagen, Denmark i Department of Occupational Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway j Centre for International Health, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway k Section of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy,