Families First: a Manitoba Indigenous Approach to Addressing the Issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printable PDF Version

CEO Appearance: Supplementary Estimates B 2019-20 Binder Table of Contents Fact Sheets Lead Exercising the Right to Vote Elections Canada’s (EC) Response to Manitoba Storms EEI-OFG Efforts by EC for Indigenous electors PPA-OSE Official languages complaints during the general election (GE) and EC CEO-COS response/proposed solutions Enhanced Services to Jewish Communities RA-LS/EEI- OFG/PPA-OSE Initiatives for target groups PPA-OSE/EEI-OFG Vote on Campus EEI-OFG Regulating Political Entities Activities to educate third parties on the new regime RA-LS/PF Enforcement and Integrity Measures to increase the accuracy of the National Register of Electors (NRoE) EEI-EDMR Social media and disinformation RA-EIO/PPA Election Administration Cost of GE IS-CFO Social media influencer campaign (including response to Written Q-122) PPA-VIC/MRIM Comparison of costs of EC’s and Australia’s voter information campaigns PPA-VIC Security of IT Equipment IS COVID-19 and election preparation IS Background Documentation Lead Placemat – Election Related Stats PPA-P&R Proximity and accessibility of polling stations (improvements for the 43rd GE) EEI Media lines on Voter Qualification/Potential Non-Citizens on the NRoE PPA-MRIM Recent responses to MP Questions (2019) PPA-P&R Registration of Expat Electors-43rd GE EEI Statement on “Enforcement of the third-party regime by the Commissioner of PPA-P&R Canada Elections” Copy of Elections Canada Departmental Plan 2020-21 IS-CFO Copy of Supplementary Estimates IS-CFO *Binder prepared for the appearance of the Chief Electoral Officer before the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs on the Subject of the Supplementary Estimates “B” 2019-20 on March 12, 2020. -

2016 Annual Report of the Chief Electoral Officer

Serving our province. Sharing your voice. The Year in Review | 2016 Annual Report Including Conduct of the 41st Provincial General Election, April 19, 2016 Servir notre province. Fair entendre votre voix. Faits saillants de l'année | Rapport annuel 2016 Y compris la tenue de la 41e élection générale provinciale du 19 avril 2016 IV Introduction 2016 Annual Report Pursuant to subsection 32(4) of the EA and subsection The Honourable Myrna Driedger September 1, 2017 107(3) of the EFA, an annual report that contains Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Dear Madame Speaker: recommendations for amendments to these Acts stands Room 244 Legislative Building referred to the Standing Committee on Legislative Affairs Winnipeg, Manitoba I have the honour of submitting to you the annual report for consideration of those matters. The above-noted R3C 0V8 on the activities of Elections Manitoba, including the subsections also provide that the Committee shall begin conduct of the 41st general election, held on April 19, its consideration of the report within 60 days after the 2016. This report is submitted pursuant to subsection report is tabled in the Assembly. 32(1) of The Elections Act (EA) and subsection 107(1) of The Election Financing Act (EFA). In accordance with Respectfully yours, subsection 32(5) of the EA and subsection 107(1) of the EFA, post-election and annual reporting under these statutes have been combined. The applicable legislation states that the Speaker must table the report in the Assembly forthwith without delay Shipra Verma CPA, CA if the Assembly is sitting or, if it is not, within 15 days Chief Electoral Officer after the next sitting begins. -

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the Period 2002 to 2012

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the period 2002 to 2012 The following list identifies the RHAs and RHA Districts in Manitoba between the period 2002 and 2012. The 11 RHAs are listed using major headings with numbers and include the MCHP - Manitoba Health codes that identify them. RHA Districts are listed under the RHA heading and include the Municipal codes that identify them. Changes / modifications to these definitions and the use of postal codes in definitions are noted where relevant. 1. CENTRAL (A - 40) Note: In the fall of 2002, Central changed their districts, going from 8 to 9 districts. The changes are noted below, beside the appropriate district area. Seven Regions (A1S) (* 2002 changed code from A8 to A1S *) '063' - Lakeview RM '166' - Westbourne RM '167' - Gladstone Town '206' - Alonsa RM 'A18' - Sandy Bay FN Cartier/SFX (A1C) (* 2002 changed name from MacDonald/Cartier, and code from A4 to A1C *) '021' - Cartier RM '321' - Headingley RM '127' - St. Francois Xavier RM Portage (A1P) (* 2002 changed code from A7 to A1P *) '090' - Macgregor Village '089' - North Norfolk RM (* 2002 added area from Seven Regions district *) '098' - Portage La Prairie RM '099' - Portage La Prairie City 'A33' - Dakota Tipi FN 'A05' - Dakota Plains FN 'A04' - Long Plain FN Carman (A2C) (* 2002 changed code from A2 to A2C *) '034' - Carman Town '033' - Dufferin RM '053' - Grey RM '112' - Roland RM '195' - St. Claude Village '158' - Thompson RM 1 Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area -

National Aboriginal Diabetes Association Annual Report

National Aboriginal Diabetes Association Annual Report Full Report Anita Ducharme, Executive Director 2014 - 2015 NADA 2014 - 2015 Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 About the National Aboriginal Diabetes Association 4 Work Plan Activities Report: Culturally Appropriate Resources 7 Work Plan Activities Report: Abor Health Fairs and Special Events 11 Work Plan Activities Report: Diabetes Resources/Social Media Links 12 Work Plan Activities Report: National Diabetes Resource Directory 14 (NDRD) British Columbia Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Alberta 15 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Saskatchewan 17 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Manitoba 19 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Ontario 21 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Quebec 23 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, New Brunswick 25 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Newfoundland/Labrador 27 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Nova Scotia 29 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Prince Edward Island 31 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Yukon 33 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Northwest Territories 35 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Nunavut 37 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Policy Handbook 39 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Just Move It 40 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Partnerships 41 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, iMD 43 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, Social Media, Twitter 44 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, CDPW Face Book Page 51 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, General Face Book Page 55 Work Plan Activities Report: NDRD, NADA Website 60 Work -

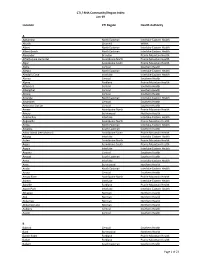

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba

Second Session - Thirty-Fifth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba STANDING COMMITTEE on MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS 40 Elizabeth II Chairman Mrs. Louise Dacquay Constituencyof Seine River VOL XL No.3 ·10 a.m., THURSDAY, JULY 18, 1991 MG-8048 ISSN 0713-956X Printedby the Office of the Queens Printer. Province of Manitoba MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-FifthLegislature LIB -liberal; NO - New Democrat; PC - Progressive Conservative NAME CONSTITUENCY PARTY. ALCOCK, Reg Osborne LIB ASHTON, Steve Thompson NO BARRETT, Becky Wellington NO CARR, James Crescentwood LIB CARSTAIRS, Sharon River Heights LIB CERILLI, Marianne Radisson NO CHEEMA, Guizar The Maples LIB CHOMIAK, Dave Kildonan NO CONNERY, Edward Portage Ia Prairie PC CUMMINGS, Glen, Hon. Ste. Rose PC DACQUAY, Louise Seine River PC DERKACH, Leonard, Hon. Roblin-Russell PC DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk NO DOER, Gary Concordia NO DOWNEY, James, Hon. Arthur-Virden PC DRIEDGER, Albert, Hon. Steinbach PC DUCHARME, Gerry,Hon. Riel PC EDWARDS, Paul St. James LIB ENNS, Harry, Hon. Lakeside PC ERNST, Jim, Hon. Charleswood PC EVANS, Clif Interlake NO EVANS, Leonard S. Brandon East NO FILMON, Gary, Hon. Tuxedo PC FINDLAY, Glen, Hon. Springfield PC FRIESEN, Jean Wolseley NO GAUDRY, Neil St. Boniface LIB GILLESHAMMER, Harold, Hon. Minnedosa PC HARPER, Elijah Rupertsland NO HELWER, Edward R. Gimli PC HICKES, George Point Douglas NO LAMOUREUX, Kevin Inkster LIB LATHLIN, Oscar The Pas NO LAURENDEAU, Marcel St. Norbert PC MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood NO MANNESS, Clayton, Hon. Morris PC MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows NO McALPINE, Gerry Sturgeon Creek PC McCRAE, James, Hon. Brandon West PC MciNTOSH, linda, Hon. Assiniboia PC MITCHELSON, Bonnie, Hon. River East PC NEUFELD, Harold, Hon. -

Packaging and Printed Paper (PPP) Program Plan 2017-2021 March 2017

Packaging and Printed Paper (PPP) Program Plan 2017-2021 March 2017 List of Acronyms ......................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Multi-Material Stewardship Manitoba Inc................................................................... 6 1.2 Regulatory Context ..................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Background ................................................................................................................ 6 1.4 Program Goals and Objectives .................................................................................... 6 1.5 MMSM Vision and Mission ......................................................................................... 6 2 Designated Materials ................................................................................................. 6 3 Steward Responsibilities ............................................................................................ 7 3.1 Obligated Stewards ....................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Voluntary Stewards .................................................................................................... 8 3.3 Rules for Stewards ..................................................................................................... -

Candidats Officiels : 42E Élection Générale

CANDIDATS OFFICIELS : 42E ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE CANDIDAT AFFILIATION AGENT CANDIDAT AFFILIATION AGENT OFFICIEL OFFICIEL AGASSIZ FORT RICHMOND CLARKE, Eileen - 54, 7E RUE, GLADSTONE PC Jodie Byram GUILLEMARD, Sarah - 732, AV. TOWNSEND, WINNIPEG PC Dana Chudley CLAYTON, Liz - N. O. 23-7-8 O., MUN. DE NORFOLK-TREHERNE PVM Henri Chatelain NAGRA, Tanjit - 33, AV. KILLARNEY, APP. 204, WINNIPEG Lib. Gordon Chandler LEGASPI, Kelly - 50, CH. HERRON, WINNIPEG NPD Kevin Dearing PROULX, Cameron - 1428, PROM. MARS, WINNIPEG PVM Grant Sharp SWANSON, Hector - 355, AV. ISABEL, APP. 4, NEEPAWA Lib. Jason Nadeau WONG, George - 26, BAIE BRIAN MONKMAN, WINNIPEG NPD Muninder Sidhu ASSINIBOIA FORT ROUGE ANDERSON, Jeff - 53, RUE LIPTON, WINNIPEG Lib. Jane Giesbrecht BEDDOME, James - 563, AV. ROSEDALE, WINNIPEG PVM Douglas Tingey DELAAT, John - 113, RUE LANARK, WINNIPEG PVM Durrenda Delaat FRIESEN, Cyndy - 254, RUE GIESBRECHT, STEINBACH Lib. Valerie Gilroy JOHNSTON, Scott - 107, PROM. EMERALD GROVE, WINNIPEG PC J. Bryce Matlashewski HEBERT, Bradley - 376, RUE OSBORNE, APP. 708, WINNIPEG MBFWD Melissa Kennedy MCKELLEP, Joe - 110, PROM. TWAIN, WINNIPEG NPD Bela Gyarmati KINEW, Wab - 127, RUE HARROW, WINNIPEG NPD Muninder Sidhu MCCRACKEN, Michael - 115, RUE CLARKE, APP. 505, WINNIPEG MF Moe Salaam BORDERLAND NABESS, Edna - 167, CH. ACADEMY, WINNIPEG PC Vaughan Crawford BRAUL, Loren - 79, RUE ALTBERGTHAL, RHINELAND Lib. Wes Sawatzky CRONK, Liz - 138, RUE GARFIELD S., WINNIPEG NPD Keith Doerksen FORT WHYTE GRAYDON, Cliff - 121, AV. BRAD, DOMINION CITY Ind. Glenn Reimer BRUSKE, Beatrice - 1029, BOUL. SCURFIELD, WINNIPEG NPD Kevin Dearing GUENTER, Josh - S. O. 10-2-3 O., RHINELAND PC R. Don Esler CAMPBELL, Sara - 92, CR. TANGLE RIDGE, WINNIPEG PVM Gloria Sisson HENRY, Ken - 186, AV. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No. 70

Monday, July 31, 2000 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MANITOBA __________________________ VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 70 FIRST SESSION, THIRTY-SEVENTH LEGISLATURE PRAYERS 1:30 O’CLOCK P.M. Mr. MARTINDALE, Chairperson of the Standing Committee on Law Amendments, presented its Eighth Report, which was read as follows: Your Committee met on Tuesday, July 25, 2000 at 6:30 p.m., Wednesday, July 26, 2000 at 6:30 p.m. and Thursday, July 27, 2000 at 2:45 p.m. in Room 255 of the Legislative Building to consider Bills referred. At the July 25, 2000 meeting, your Committee elected Mr. REID as Vice-Chairperson. At the July 26, 2000 meeting, your Committee Elected Mr. MARTINDALE as Chairperson and Mr. SMITH (Brandon West) as Vice-Chairperson. At the July 25, 2000 meeting, your Committee agreed, by motion, on a counted vote of Yeas 6, Nays 4, to the following motion: THAT presentations be limited to 15 minutes with a maximum 5 minutes for questions. At the meetings held on July 25 and 26, your Committee heard representation on Bills as follows: Bill (No. 12) – The Public Schools Amendment Act/Loi modifiant la Loi sur les écoles publiques Gerald Huebner Manitoba Association of Christian Homeschools Norbert and Debbie Maertins Private Citizens Bernd Rist Private Citizen Abe Janzen Private Citizen Dr. Terry Lewis Private Citizen Marion Hart Private Citizen Bill (No. 42) – The Public Schools Amendment and Consequential Amendments Act/Loi modifiant la Loi sur les écoles publiques et modifications corrélatives Theresa Ducharme People for Equal Participation Inc. Rey Toews & Carolyn Duhamel President, Manitoba Association of School Trustees Len Schieman Rhineland School Division #18 280 Monday, July 31, 2000 Fran Frederickson & Val Weiss Chair, Interlake School Division Bart Michaleski President, Manitoba Association of School Business Officials Jim Murray & Linda Ross Chair, Brandon School Division #40 Floyd Martens Chair, Intermountain School Division Ron G. -

Grade 9 Social Studies (10F): Canada in the Contemporary World

Grade 9 Social Studies (10F): Canada in the Contemporary World A Course for Independent Study Field Validation Version Grade 9 Social Studies (10F): Canada in the Contemporary World A Course for Independent Study Field Validation Version 2013, 2019 Manitoba Education Manitoba Education Cataloguing in Publication Data Grade 9 social studies (10F) : Canada in the contemporary world : a course for independent study—Field validation version Includes bibliographical references. ISBN: 978-0-7711-5556-7 1. Canada—Study and teaching (Secondary). 2. Canada—Study and teaching (Secondary)—Manitoba. 3. Civics, Canadian—Study and teaching (Secondary). 4. Social sciences—Study and teaching (Secondary)—Manitoba. 5. Social sciences—Programmed instruction. 6. Distance education—Manitoba. 7. Correspondence schools and courses—Manitoba. I. Manitoba. Manitoba Education. 320.471 Copyright © 2013, 2019, the Government of Manitoba, represented by the Minister of Education. Manitoba Education Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Every effort has been made to acknowledge original sources and to comply with copyright law. If cases are identified where this has not been done, please notify Manitoba Education. Errors or omissions will be corrected in a future edition. Sincere thanks to the authors, artists, and publishers who allowed their original material to be used. All images found in this resource are copyright protected and should not be extracted, accessed, or reproduced for any purpose other than for their intended educational use in this resource. Any websites referenced -

DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

Second Session - Fortieth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable Daryl Reid Speaker Vol. LXV No. 4 - 1:30 p.m., Thursday, November 22, 2012 ISSN 0542-5492 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Fortieth Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation ALLAN, Nancy, Hon. St. Vital NDP ALLUM, James Fort Garry-Riverview NDP ALTEMEYER, Rob Wolseley NDP ASHTON, Steve, Hon. Thompson NDP BJORNSON, Peter, Hon. Gimli NDP BLADY, Sharon Kirkfield Park NDP BRAUN, Erna Rossmere NDP BRIESE, Stuart Agassiz PC CALDWELL, Drew Brandon East NDP CHIEF, Kevin, Hon. Point Douglas NDP CHOMIAK, Dave, Hon. Kildonan NDP CROTHERS, Deanne St. James NDP CULLEN, Cliff Spruce Woods PC DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk NDP DRIEDGER, Myrna Charleswood PC EICHLER, Ralph Lakeside PC EWASKO, Wayne Lac du Bonnet PC FRIESEN, Cameron Morden-Winkler PC GAUDREAU, Dave St. Norbert NDP GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Liberal GOERTZEN, Kelvin Steinbach PC GRAYDON, Cliff Emerson PC HELWER, Reg Brandon West PC HOWARD, Jennifer, Hon. Fort Rouge NDP IRVIN-ROSS, Kerri, Hon. Fort Richmond NDP JHA, Bidhu Radisson NDP KOSTYSHYN, Ron, Hon. Swan River NDP LEMIEUX, Ron, Hon. Dawson Trail NDP MACKINTOSH, Gord, Hon. St. Johns NDP MAGUIRE, Larry Arthur-Virden PC MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood NDP MARCELINO, Flor, Hon. Logan NDP MARCELINO, Ted Tyndall Park NDP MELNICK, Christine, Hon. Riel NDP MITCHELSON, Bonnie River East PC NEVAKSHONOFF, Tom Interlake NDP OSWALD, Theresa, Hon. Seine River NDP PALLISTER, Brian Fort Whyte PC PEDERSEN, Blaine Midland PC PETTERSEN, Clarence Flin Flon NDP REID, Daryl, Hon. Transcona NDP ROBINSON, Eric, Hon. Kewatinook NDP RONDEAU, Jim, Hon.