Iye Ohdakapi: Their Stories Manitoba Dakota Elders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printable PDF Version

CEO Appearance: Supplementary Estimates B 2019-20 Binder Table of Contents Fact Sheets Lead Exercising the Right to Vote Elections Canada’s (EC) Response to Manitoba Storms EEI-OFG Efforts by EC for Indigenous electors PPA-OSE Official languages complaints during the general election (GE) and EC CEO-COS response/proposed solutions Enhanced Services to Jewish Communities RA-LS/EEI- OFG/PPA-OSE Initiatives for target groups PPA-OSE/EEI-OFG Vote on Campus EEI-OFG Regulating Political Entities Activities to educate third parties on the new regime RA-LS/PF Enforcement and Integrity Measures to increase the accuracy of the National Register of Electors (NRoE) EEI-EDMR Social media and disinformation RA-EIO/PPA Election Administration Cost of GE IS-CFO Social media influencer campaign (including response to Written Q-122) PPA-VIC/MRIM Comparison of costs of EC’s and Australia’s voter information campaigns PPA-VIC Security of IT Equipment IS COVID-19 and election preparation IS Background Documentation Lead Placemat – Election Related Stats PPA-P&R Proximity and accessibility of polling stations (improvements for the 43rd GE) EEI Media lines on Voter Qualification/Potential Non-Citizens on the NRoE PPA-MRIM Recent responses to MP Questions (2019) PPA-P&R Registration of Expat Electors-43rd GE EEI Statement on “Enforcement of the third-party regime by the Commissioner of PPA-P&R Canada Elections” Copy of Elections Canada Departmental Plan 2020-21 IS-CFO Copy of Supplementary Estimates IS-CFO *Binder prepared for the appearance of the Chief Electoral Officer before the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs on the Subject of the Supplementary Estimates “B” 2019-20 on March 12, 2020. -

2016 Annual Report of the Chief Electoral Officer

Serving our province. Sharing your voice. The Year in Review | 2016 Annual Report Including Conduct of the 41st Provincial General Election, April 19, 2016 Servir notre province. Fair entendre votre voix. Faits saillants de l'année | Rapport annuel 2016 Y compris la tenue de la 41e élection générale provinciale du 19 avril 2016 IV Introduction 2016 Annual Report Pursuant to subsection 32(4) of the EA and subsection The Honourable Myrna Driedger September 1, 2017 107(3) of the EFA, an annual report that contains Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Dear Madame Speaker: recommendations for amendments to these Acts stands Room 244 Legislative Building referred to the Standing Committee on Legislative Affairs Winnipeg, Manitoba I have the honour of submitting to you the annual report for consideration of those matters. The above-noted R3C 0V8 on the activities of Elections Manitoba, including the subsections also provide that the Committee shall begin conduct of the 41st general election, held on April 19, its consideration of the report within 60 days after the 2016. This report is submitted pursuant to subsection report is tabled in the Assembly. 32(1) of The Elections Act (EA) and subsection 107(1) of The Election Financing Act (EFA). In accordance with Respectfully yours, subsection 32(5) of the EA and subsection 107(1) of the EFA, post-election and annual reporting under these statutes have been combined. The applicable legislation states that the Speaker must table the report in the Assembly forthwith without delay Shipra Verma CPA, CA if the Assembly is sitting or, if it is not, within 15 days Chief Electoral Officer after the next sitting begins. -

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the Period 2002 to 2012

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the period 2002 to 2012 The following list identifies the RHAs and RHA Districts in Manitoba between the period 2002 and 2012. The 11 RHAs are listed using major headings with numbers and include the MCHP - Manitoba Health codes that identify them. RHA Districts are listed under the RHA heading and include the Municipal codes that identify them. Changes / modifications to these definitions and the use of postal codes in definitions are noted where relevant. 1. CENTRAL (A - 40) Note: In the fall of 2002, Central changed their districts, going from 8 to 9 districts. The changes are noted below, beside the appropriate district area. Seven Regions (A1S) (* 2002 changed code from A8 to A1S *) '063' - Lakeview RM '166' - Westbourne RM '167' - Gladstone Town '206' - Alonsa RM 'A18' - Sandy Bay FN Cartier/SFX (A1C) (* 2002 changed name from MacDonald/Cartier, and code from A4 to A1C *) '021' - Cartier RM '321' - Headingley RM '127' - St. Francois Xavier RM Portage (A1P) (* 2002 changed code from A7 to A1P *) '090' - Macgregor Village '089' - North Norfolk RM (* 2002 added area from Seven Regions district *) '098' - Portage La Prairie RM '099' - Portage La Prairie City 'A33' - Dakota Tipi FN 'A05' - Dakota Plains FN 'A04' - Long Plain FN Carman (A2C) (* 2002 changed code from A2 to A2C *) '034' - Carman Town '033' - Dufferin RM '053' - Grey RM '112' - Roland RM '195' - St. Claude Village '158' - Thompson RM 1 Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area -

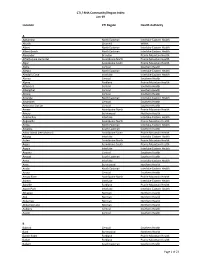

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Packaging and Printed Paper (PPP) Program Plan 2017-2021 March 2017

Packaging and Printed Paper (PPP) Program Plan 2017-2021 March 2017 List of Acronyms ......................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Multi-Material Stewardship Manitoba Inc................................................................... 6 1.2 Regulatory Context ..................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Background ................................................................................................................ 6 1.4 Program Goals and Objectives .................................................................................... 6 1.5 MMSM Vision and Mission ......................................................................................... 6 2 Designated Materials ................................................................................................. 6 3 Steward Responsibilities ............................................................................................ 7 3.1 Obligated Stewards ....................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Voluntary Stewards .................................................................................................... 8 3.3 Rules for Stewards ..................................................................................................... -

Candidats Officiels : 42E Élection Générale

CANDIDATS OFFICIELS : 42E ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE CANDIDAT AFFILIATION AGENT CANDIDAT AFFILIATION AGENT OFFICIEL OFFICIEL AGASSIZ FORT RICHMOND CLARKE, Eileen - 54, 7E RUE, GLADSTONE PC Jodie Byram GUILLEMARD, Sarah - 732, AV. TOWNSEND, WINNIPEG PC Dana Chudley CLAYTON, Liz - N. O. 23-7-8 O., MUN. DE NORFOLK-TREHERNE PVM Henri Chatelain NAGRA, Tanjit - 33, AV. KILLARNEY, APP. 204, WINNIPEG Lib. Gordon Chandler LEGASPI, Kelly - 50, CH. HERRON, WINNIPEG NPD Kevin Dearing PROULX, Cameron - 1428, PROM. MARS, WINNIPEG PVM Grant Sharp SWANSON, Hector - 355, AV. ISABEL, APP. 4, NEEPAWA Lib. Jason Nadeau WONG, George - 26, BAIE BRIAN MONKMAN, WINNIPEG NPD Muninder Sidhu ASSINIBOIA FORT ROUGE ANDERSON, Jeff - 53, RUE LIPTON, WINNIPEG Lib. Jane Giesbrecht BEDDOME, James - 563, AV. ROSEDALE, WINNIPEG PVM Douglas Tingey DELAAT, John - 113, RUE LANARK, WINNIPEG PVM Durrenda Delaat FRIESEN, Cyndy - 254, RUE GIESBRECHT, STEINBACH Lib. Valerie Gilroy JOHNSTON, Scott - 107, PROM. EMERALD GROVE, WINNIPEG PC J. Bryce Matlashewski HEBERT, Bradley - 376, RUE OSBORNE, APP. 708, WINNIPEG MBFWD Melissa Kennedy MCKELLEP, Joe - 110, PROM. TWAIN, WINNIPEG NPD Bela Gyarmati KINEW, Wab - 127, RUE HARROW, WINNIPEG NPD Muninder Sidhu MCCRACKEN, Michael - 115, RUE CLARKE, APP. 505, WINNIPEG MF Moe Salaam BORDERLAND NABESS, Edna - 167, CH. ACADEMY, WINNIPEG PC Vaughan Crawford BRAUL, Loren - 79, RUE ALTBERGTHAL, RHINELAND Lib. Wes Sawatzky CRONK, Liz - 138, RUE GARFIELD S., WINNIPEG NPD Keith Doerksen FORT WHYTE GRAYDON, Cliff - 121, AV. BRAD, DOMINION CITY Ind. Glenn Reimer BRUSKE, Beatrice - 1029, BOUL. SCURFIELD, WINNIPEG NPD Kevin Dearing GUENTER, Josh - S. O. 10-2-3 O., RHINELAND PC R. Don Esler CAMPBELL, Sara - 92, CR. TANGLE RIDGE, WINNIPEG PVM Gloria Sisson HENRY, Ken - 186, AV. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

Second Session - Fortieth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable Daryl Reid Speaker Vol. LXV No. 4 - 1:30 p.m., Thursday, November 22, 2012 ISSN 0542-5492 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Fortieth Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation ALLAN, Nancy, Hon. St. Vital NDP ALLUM, James Fort Garry-Riverview NDP ALTEMEYER, Rob Wolseley NDP ASHTON, Steve, Hon. Thompson NDP BJORNSON, Peter, Hon. Gimli NDP BLADY, Sharon Kirkfield Park NDP BRAUN, Erna Rossmere NDP BRIESE, Stuart Agassiz PC CALDWELL, Drew Brandon East NDP CHIEF, Kevin, Hon. Point Douglas NDP CHOMIAK, Dave, Hon. Kildonan NDP CROTHERS, Deanne St. James NDP CULLEN, Cliff Spruce Woods PC DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk NDP DRIEDGER, Myrna Charleswood PC EICHLER, Ralph Lakeside PC EWASKO, Wayne Lac du Bonnet PC FRIESEN, Cameron Morden-Winkler PC GAUDREAU, Dave St. Norbert NDP GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Liberal GOERTZEN, Kelvin Steinbach PC GRAYDON, Cliff Emerson PC HELWER, Reg Brandon West PC HOWARD, Jennifer, Hon. Fort Rouge NDP IRVIN-ROSS, Kerri, Hon. Fort Richmond NDP JHA, Bidhu Radisson NDP KOSTYSHYN, Ron, Hon. Swan River NDP LEMIEUX, Ron, Hon. Dawson Trail NDP MACKINTOSH, Gord, Hon. St. Johns NDP MAGUIRE, Larry Arthur-Virden PC MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood NDP MARCELINO, Flor, Hon. Logan NDP MARCELINO, Ted Tyndall Park NDP MELNICK, Christine, Hon. Riel NDP MITCHELSON, Bonnie River East PC NEVAKSHONOFF, Tom Interlake NDP OSWALD, Theresa, Hon. Seine River NDP PALLISTER, Brian Fort Whyte PC PEDERSEN, Blaine Midland PC PETTERSEN, Clarence Flin Flon NDP REID, Daryl, Hon. Transcona NDP ROBINSON, Eric, Hon. Kewatinook NDP RONDEAU, Jim, Hon. -

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

Manitoba Association of Native Firefighters, Inc. (MANFF) Was Formed in 1991

ManitobaManitoba AssociationAssociation ofof NativeNative Firefighters,Firefighters, Inc.Inc. History of MANFF The Manitoba Association of Native Firefighters, Inc. (MANFF) was formed in 1991. Our membership is composed of, and directed by, Manitoba First Nation Fire Chiefs. We receive direction from the Fire Chiefs, who elect Board of Directors. Our Mandate In 1991, MANFF received the mandate to continue to deliver the following programs to First Nation communities: ➱Fire Safety ➱Emergency Management ➱Public Education Contribution Agreement We at MANFF, along with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC) and the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) entered into a Contribution Agreement for the delivery of Regional Fire Safety and Emergency Management programs. First Nations Emergency Management We provide Emergency Management services to First Nations on 24 hours, 7 days a week basis to First Nations, including Response, Mitigation & Recovery. ➱Emergency Response Plan Development ➱Emergency Social Services ➱Disaster Financial Assistance (DFA) ➱ Work with EMO to complete First Nation DFA Inspections Improved Emergency Operations Centre We improved our EOC with many productive upgrades, including multiple screens to monitor databases and satellite imagery; and also installed a SMARTboard in our training facility. Emergency Response Plans Upon review of the Spring Flood Report issued by Manitoba Water Stewardship, we began assisting with Emergency Response Plans, and preparing for future implementation for the following First Nation communities: Interlake Sandbag Operation In March, we worked with Manitoba EMO and the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development (AANDC) to assist with the surrounding First Nation communities, which included: •Pinaymootang •Little Saskatchewan •Lake St. Martin. The Site Operation was at the Pinaymootang Arena. -

Trailblazers of the FIRST 100 YEARS

Women of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Trailblazers OF THE FIRST 100 YEARS 1916 – 2016 TIVE ASS LA EM IS B G L E Y L MANITOBA On January 28, 1916, Bill No. 4 – An Act to amend “The Manitoba Election Act” received Royal Assent. The passage of this Act granted most Manitoba women the right to vote and to run for public office. Manitoba was the first province in Canada to win the right to vote for women. Nellie McClung was one of the Manitoba women involved in campaigning for the women’s right to vote in 1916. She was also one of Canada’s Famous Five who initiated and won the Persons Case, to have women become recognized as persons under Canadian law in 1929. In recognition of Manitoba’s centennial of most women receiving the right to vote, we pay tribute to a select handful of women trailblazers who achieved first in their field since that time. 2 TRAILBLAZERS 1916 - 2016 Trailblazers OF THE FIRST 100 YEARS Foreword by JoAnn McKerlie-Korol, Director of Education and Outreach Services of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba On January 28, 1916, legislation passed that granted women the right to vote and to run for public office. On June 29, 1920, the first woman, Edith Rogers, was elected to represent the constituency of Winnipeg. This was just the beginning of the “firsts” for Manitoba’s women in the Legislative Assembly. Celebrating the first 100 years since the passage of this legislation, only 51 women have been elected to the Manitoba Legislative Assembly as elected MLAs and only a small number have served as Officers of the Legislative Assembly. -

Is the NDP As Manitoba's Natural Governing Party

Is the NDP Manitoba’s Natural Governing Party? A Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association Edmonton, AB. June 14, 2012 Nelson Wiseman Dept. of Political Science University of Toronto [email protected] In the lexicon of Canadian politics, academics and journalists have long associated the term “natural governing party” with the federal Liberal party1 and reasonably so: the Liberals governed for 80 years, or 72 percent, of the 110 years between 1896 and 2006. In Alberta, the Progressive Conservatives’ unbroken record of majority governments for more than the past four decades qualifies them as well for the appellation “natural governing party.”2 This paper asks if the New Democratic Party (NDP) may be considered as Manitoba’s natural governing party. By the time of Manitoba’s next election, the party will have governed in 33 years, or 59 percent, of the 46 years since its initial ascension to office in 1969. A generation of new Manitoban voters in the 2015 election will have known only an NDP government in their politically conscious lives. To them, the “natural” political order will be NDP government. If a measure of dominance is whether a governing party commands a majority of parliamentary seats, then the Manitoba NDP’s record exceeds the record of the federal Liberals. In the 28 federal elections since 1921 – when the possibility of minority governments first arose with the appearance of third parties in Parliament – the Liberals secured majority mandates in 12, or only 43 percent, of those contests. The Manitoba NDP, in contrast, has won outright majorities in 58 percent of the elections since 1969.