Title Collecting Rooms: Objects, Identities and Domestic Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marion Grierson Transcription.Docx

COPYRIGHT: No use may be made of any interview material without the permission of the BECTU History Project (http://www.historyproject.org.uk/). Copyright of interview material is vested in the BECTU History Project (formerly the ACTT History Project) and the right to publish some excerpts may not be allowed. CITATION: Women’s Work in British Film and Television, Marian Grierson, http://bufvc.ac.uk/bectu/oral- histories/bectu-oh [date accessed] By accessing this transcript, I confirm that I am a student or staff member at a UK Higher Education Institution or member of the BUFVC and agree that this material will be used solely for educational, research, scholarly and non- commercial purposes only. I understand that the transcript may be reproduced in part for these purposes under the Fair Dealing provisions of the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act. For the purposes of the Act, the use is subject to the following: The work must be used solely to illustrate a point The use must not be for commercial purposes The use must be fair dealing (meaning that only a limited part of work that is necessary for the research project can be used) The use must be accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement. Guidelines for citation and proper acknowledgement must be followed (see above). It is prohibited to use the material for commercial purposes and access is limited exclusively to UK Higher Education staff and students and members of BUFVC. I agree to the above terms of use and that I will not edit, modify or use this material in ways that misrepresent the interviewees’ words, might be defamatory or likely to bring BUFVC, University of Leeds or my HEI into disrepute. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources The analyses of various films and television programmes undertaken in this book are intended to function ‘interactively’ with screenings of the films and programmes. To this end, a complete list of works to accompany each chapter is provided below. Certain of these works are available from national and international distribution companies. Specific locations in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia for each of the listed works are, nevertheless, provided below. The entries include running time and format (16 mm, VHS, or DVD) for each work. (Please note: In certain countries films require copyright clearance for public screening.) Also included below are further or additional screenings of works not analysed or referred to in each chapter. This information is supplemented by suggested further reading. 1 ‘Believe me, I’m of the world’: documentary representation Further reading Corner, J. ‘Civic visions: forms of documentary’ in J. Corner, Television Form and Public Address (London: Edward Arnold, 1995). Corner, J. ‘Television, documentary and the category of the aesthetic’, Screen, 44, 1 (2003) 92–100. Nichols, B. Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994). Renov, M. ‘Toward a poetics of documentary’ in M. Renov (ed.), Theorizing Documentary (New York: Routledge, 1993). 2 Men with movie cameras: Flaherty and Grierson Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty, 1922. 55 min. (Alternative title: Nanook of the North: A Story -

1 "Documentary Films" an Entry in the Encylcopedia of International Media

1 "Documentary Films" An entry in the Encylcopedia of International Media and Communication, published by the Academic Press, San Diego, California, 2003 2 DOCUMENTARY FILMS Jeremy Murray-Brown, Boston University, USA I. Introduction II. Origins of the documentary III. The silent film era IV. The sound film V. The arrival of television VI. Deregulation: the 1980s and 1990s VII. Conclusion: Art and Facts GLOSSARY Camcorders Portable electronic cameras capable of recording video images. Film loop A short length of film running continuously with the action repeated every few seconds. Kinetoscope Box-like machine in which moving images could be viewed by one person at a time through a view-finder. Music track A musical score added to a film and projected synchronously with it. In the first sound films, often lasting for the entire film; later blended more subtly with dialogue and sound effects. Nickelodeon The first movie houses specializing in regular film programs, with an admission charge of five cents. On camera A person filmed standing in front of the camera and often looking and speaking into it. Silent film Film not accompanied by spoken dialogue or sound effects. Music and sound effects could be added live in the theater at each performance of the film. Sound film Film for which sound is recorded synchronously with the picture or added later to give this effect and projected synchronously with the picture. Video Magnetized tape capable of holding electronic images which can be scanned electronically and viewed on a television monitor or projected onto a screen. Work print The first print of a film taken from its original negative used for editing and thus not fit for public screening. -

International & Australian Posters

International & Australian Posters Collectors’ List No. 157, 2012 Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke Street) Kensington (Sydney) NSW Ph: (02) 9663 4848; Fax: (02) 9663 4447 Email: [email protected] Web: joseflebovicgallery.com JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY Australian & International Events, Performances... Established 1977 1. “The Recruiting Officer,” 1790. Letterpress 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney) NSW handbill, 25.1 x 17.2cm (paper). Laid down on acid- free paper. Post: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia $1,250 Text includes “Theatre Royal, Covent Garden… This present Tel: (02) 9663 4848 • Fax: (02) 9663 4447 • Intl: (+61-2) Thursday, February 25, 1790, will be presented a comedy, called The Recruiting Officer. After which will be performed, Email: [email protected] • Web: joseflebovicgallery.com for the 39th time, a pantomime, called Harlequin’s Chpalet Open: Wed to Fri 1-6pm, Sat 12-5pm, or by appointment • ABN 15 800 737 094 [sic]…” A cast list for both plays is included. Written by George Farquhar in 1706, The Recruiting Officer was the Member of • Association of International Photography Art Dealers Inc. first play performed in Australia, in June 1789 in Sydney. This International Fine Print Dealers Assoc. • Australian Art & Antique Dealers Assoc. handbill is for the London performance of 1790. 2. George E. Mason (Brit.). Mason’s Instructions For COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 157, 2012 Fingering The Fretted Violin. A Diagram For The Use Of Students, c1890. Lithograph, International & Australian Posters 64.6 x 25cm. Foxing and stains overall, repaired tears, creases, pinholes, and missing portions. On exhibition from Wednesday, 13 June to Saturday, 4 August. -

Pdf/ Mow/Nomination Forms United Kingdom Battle of the Somme (Accessed 18.04.2014)

Notes Introduction: Critical and Historical Perspectives on British Documentary 1. Forsyth Hardy, ‘The British Documentary Film’, in Michael Balcon, Ernest Lindgren, Forsyth Hardy and Roger Manvell, Twenty Years of British Film 1925–1945 (London, 1947), p.45. 2. Arts Enquiry, The Factual Film: A Survey sponsored by the Dartington Hall Trustees (London, 1947), p.11. 3. Paul Rotha, Documentary Film (London, 4th edn 1968 [1936]), p.97. 4. Roger Manvell, Film (Harmondsworth, rev. edn 1946 [1944]), p.133. 5. Paul Rotha, with Richard Griffith, The Film Till Now: A Survey of World Cinema (London, rev. edn 1967 [1930; 1949]), pp.555–6. 6. Michael Balcon, Michael Balcon presents ...A Lifetime of Films (London, 1969), p.130. 7. André Bazin, What Is Cinema? Volume II, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley, 1971), pp.48–9. 8. Ephraim Katz, The Macmillan International Film Encyclopedia (London, 1994), p.374. 9. Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction (New York, 1994), p.352. 10. John Grierson, ‘First Principles of Documentary’, in Forsyth Hardy (ed.), Grierson on Documentary (London, 1946), pp.79–80. 11. Ibid., p.78. 12. Ibid., p.79. 13. This phrase – sometimes quoted as ‘the creative interpretation of actual- ity’ – is universally credited to Grierson but the source has proved elusive. It is sometimes misquoted with ‘reality’ substituted for ‘actuality’. In the early 1940s, for example, the journal Documentary News Letter, published by Film Centre, which Grierson founded, carried the banner ‘the creative interpretation of reality’. 14. Rudolf Arnheim, Film as Art, trans. L. M. Sieveking and Ian F. D. Morrow (London, 1958 [1932]), p.55. -

Listen to Britain: and Other Films by Humphrey Jennings by Dean W

Listen To Britain: And Other Films By Humphrey Jennings By Dean W. Duncan The breadth and the depth of Jennings’ films owe much to the rather roundabout course by which he became a filmmaker. He was born in 1907, in a village on England’s eastern coast. His mother and father were guild socialists, sharing that movement’s reverence for the past, its love for things communal, and its deep suspicion of industrialization and the machine age. Their son, who would come to know much of both arts and crafts, and who would eventually be uniquely successful in melding tradition and modernity, was well-educated and well-read, and his interests ranged very widely indeed. He received a scholarship to Cambridge University, where he studied English literature and where all of his youthful enthusiasms coalesced into a remarkable flurry of activity and accomplishment. Jennings excelled in his chosen field, effecting an extraordinary immersion in the major movements, the signal works and authors, the main periods and issues in English literature. He also founded and wrote for a literary magazine. He oversaw an edition (from the quarto) of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, and his doctoral work – unfinished, as it turned out – on the 18th century poet Thomas Gray had, by all accounts, great merit and promise. The fact that he didn’t finish his dissertation had something to do with all the other fields in which he also chose to work. All through his studies Jennings was, heavily, and eventually professionally, involved in theatrical production. He was an actor, and a designer of real ambition and genius. -

NIGHT MAIL Is a November, 2017 LVCA Dvd Donation to the Hugh Stouppe Memorial Library of the Heritage United Methodist Church of Ligonier, Pennsylvania

NIGHT MAIL is a November, 2017 LVCA dvd donation to the Hugh Stouppe Memorial Library of the Heritage United Methodist Church of Ligonier, Pennsylvania. Here’s Kino Ken’s review of that dvd film. 18 of a possible 20 points ****1/2 of a possible ***** Great Britain 1936 black-and-white 23 minutes live action short experimental documentary GPO Film Unit (General Post Office) Producers: Harry Watt and Basil Wright Key: *indicates outstanding technical achievement or performance Points: 2 Editing: Basil Wright*, Alberto Cavalcanti*, and Richard McNaughton* 2 Cinematography: Henry Edward Fowle* and Jonah Jones* 2 Commentary: Wystan Hugh Auden* 2 Narrators: John Grierson* and Stuart Legg* (and Pat Jackson?) 2 Music: Benjamin Britten* 1 Locations 2 Sound Direction: Wystan Hugh Auden*, Benjamin Britten*, and Alberto Cavalcanti* Sound Recordists: Edward A. Pawley and C. F. Sullivan 1 Cast: Arthur Clarke, engineer and Robert Rae, senior driver for LMS Railway 2 Creativity 2 Insightfulness 18 total points A production of Great Britain’s GPO Film Unit supervised by producer John Grierson, NIGHT MAIL from 1936 is a black-and-white short documentary that even now rivets attention due to driving rhythm and dramatically insistent delivery of Wystan Hugh Auden’s dramatically onrushing poetry. Underscored by decidedly low-key music from Benjamin Britten, the film follows a mail express through one night on its run from London’s Euston Station north to the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. Getting privileged over regular passenger trains, whose riders chafe at temporary shuntings, it speeds along at a mile-devouring rate through meadowlands and sleeping hamlets in the Heart of England, where alert farmers get morning paper deliveries from mail sorters aboard. -

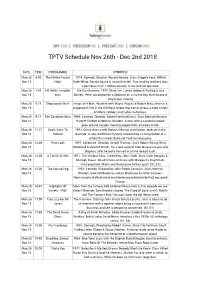

TPTV Schedule Nov 26Th - Dec 2Nd 2018

TPTV Schedule Nov 26th - Dec 2nd 2018 DATE TIME PROGRAMME SYNOPSIS Mon 26 6:00 The Million Pound 1954. Comedy. Director: Ronald Neame. Stars Gregory Peck, Wilfrid Nov 18 Note Hyde-White, Ronald Squire & Joyce Grenfell. Two wealthy brothers loan a penniless man 1 million pounds, in the form of one note. Mon 26 7:45 HG Wells' Invisible The Gun Runners. 1959. Stars Tim Turner, Deborah Watling & Lisa Nov 18 Man Daniely. Peter accompanies a diplomat on a visit to Bay Akim to prove they're gun running Mon 26 8:15 Stagecoach West Image of A Man. Western with Wayne Rogers & Robert Bray, who run a Nov 18 stagecoach line in the Old West where they come across a wide variety of killers, robbers and ladies in distress. Mon 26 9:15 The Sandwich Man 1966. Comedy. Director: Robert Hartford-Davis. Stars Michael Bentine, Nov 18 Harry H Corbett & Norman Wisdom. A man with a sandwich-board goes around London meeting people from all walks of life. Mon 26 11:15 Death Goes To 1953. Crime drama with Barbara Murray and Gordon Jackson in the Nov 18 School lead role. A rare, old British mystery surrounding a strangulation at a school that needs Scotland Yard to investigate. Mon 26 12:30 Time Lock 1957. Adventure. Director: Gerald Thomas. Stars Robert Beatty, Betty Nov 18 McDowall & Vincent Winter. It's a race against time to save six-year old, Stephen, after he locks himself in a time locked vault. Mon 26 14:00 A Family At War 1971. The 48 Hour Pass. -

Documentary Touchstones II Instructor: Michael Fox Thursdays, 10Am-12 Noon, September 28-November 2, 2017 [email protected]

Documentary Touchstones II Instructor: Michael Fox Thursdays, 10am-12 noon, September 28-November 2, 2017 [email protected] The pioneering and innovative films that paved the way for the contemporary documentary are well known yet rarely shown. This screening-and-discussion class surveys several canonical works of lasting power and influence, from Man with a Movie Camera to World War II propaganda films to latter-century hybrids and essay films. The discussion will encompass such perennial issues as the effect of the camera’s presence on the action and people being filmed, the filmmaker as activist (or propagandist), the use of metaphor and poetry, the intersection of reality, truth and storytelling, and our evolving relationship to images. Sept. 28 Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, Soviet Union, 1929) 68 min A day in the life of a city (though it was actually shot in Moscow, Kiev, Odessa and elsewhere) from dawn until dusk. After an opening statement, there are no words (neither voice-over nor titles), just dazzling imagery kinetically edited—a celebration of the modern city with an emphasis on its buildings and machinery. Voted the greatest documentary of all time in Sight & Sound’s 2014 poll. Soviet director Dziga Vertov (1896-1954), pseudonym of Denis Arkadyevich Kaufman, developed the kino-glaz (film-eye) theory that the camera is an instrument—much like the human eye—that’s best used to explore the actual happenings of real life. He had an international impact on the development of documentaries and cinema realism during the 1920s. Vertov sought to create a language of cinema, free from theatrical influence and artificial studio staging. -

Pat Jackson (Director, Documentary Filmmaker) B

Pat Jackson (director, documentary filmmaker) b. 25/3/1916 by admin — last modified Jul 28, 2008 05:40 PM BIOGRAPHY: Pat Jackson entered the film industry in 1933 as an assistant at the GPO Film Unit (later the Crown Film Unit). After working on Night Mail (1936) among other productions, he made his directorial debut in 1938 with The Horsey Mail. He came to prominence as a documentary filmmaker during WWII and is credited with developing the ‘story documentary’. His most celebrated production in this period was Western Approaches (1944), shot at sea in Technicolor, and its success led him to be placed under contract at MGM in America. It was not a happy period and he directed only one film, Shadow on the Wall (1949), before returning to work in Britain. His British feature films display a strong documentary influence and include the hospital drama White Corridors (1951) and The Birthday Present. Working in a different vein, he also directed the comedy What A Carve Up! (1961). SUMMARY: In this lengthy interview, Jackson talks to John Legard about his memories of the British documentary movement, the atmosphere and personalities of the GPO Film Unit and particularly the influence of Harry Watt and the idea of the story documentary on Jackson’s own work. He recalls working on specific productions such as Night Mail (1936), The Saving of Bill Blewitt (1936), London Can Take It (1940) and Patent Ductus Arteriosus (1947). He gives a detailed account of the production difficulties on Western Approaches, and of his unhappy sojourn in California. -

Moma to OCNCLUDE PART ONE of BRITISH FILM RETROSPECTIVE

The Museum of Modern Art Department of Film 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART #81 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MoMA TO CONCLUDE PART ONE OF BRITISH FILM RETROSPECTIVE WITH POST-WAR FILMS OF EALING STUDIOS MICHAEL BALCON: THE PURSUIT OF BRITISH CINEMA, Part One of The Museum of Modern Art's massive survey of British film history, will be devoted in its final weeks to the post-war work of producer Michael Balcon at Ealing Studios. This section of the two-part series, shown in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1, will conclude on February 5. The period after World War II was one of the most productive for Balcon, who, as the unofficial statesman and spokesman of the British film industry, worked tire lessly to help create an indigenous British cinema. The January and February pro grams at MoMA will include not only the celebrated Whisky Galore (known in the U.S. as Tight Little Island) but also three of Alec Guinness's most famous comedies, The Lavender Hill Mob, The Man in the White Suit, and The Ladykillers. Also among the best-known Ealings are the moving, almost pacific reminiscence of corvette duty during World War II, The Cruel Sea, and Alexander Mackendrick's poignant and unsen timental account of a deaf child's education, Mandy. From Basil Dearden come two thrillers: the popular police procedural The Blue Lamp, in which a young Dirk Bo- garde plays a murderous delinquent, and the lesser-known Pool of London, a shadowy dockside drama.