Law and Institutions in the Shire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythlore Index Plus

MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS MYTHLORE ISSUES 1–137 with Tolkien Journal Mythcon Conference Proceedings Mythopoeic Press Publications Compiled by Janet Brennan Croft and Edith Crowe 2020. This work, exclusive of the illustrations, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Tim Kirk’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with his kind permission. Sarah Beach’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with her kind permission. Copyright Sarah L. Beach 2007. MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS An Index to Selected Publications of The Mythopoeic Society MYTHLORE, ISSUES 1–137 TOLKIEN JOURNAL, ISSUES 1–18 MYTHOPOEIC PRESS PUBLICATIONS AND MYTHCON CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS COMPILED BY JANET BRENNAN CROFT AND EDITH CROWE Mythlore, January 1969 through Fall/Winter 2020, Issues 1–137, Volume 1.1 through 39.1 Tolkien Journal, Spring 1965 through 1976, Issues 1–18, Volume 1.1 through 5.4 Chad Walsh Reviews C.S. Lewis, The Masques of Amen House, Sayers on Holmes, The Pedant and the Shuffly, Tolkien on Film, The Travelling Rug, Past Watchful Dragons, The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America, Perilous and Fair, and Baptism of Fire Narnia Conference; Mythcon I, II, III, XVI, XXIII, and XXIX Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Janet Brennan Croft .....................................................................................................................................1 -

LOTR and Beowulf: I Need a Hero

Jestice/English 4 Lord of the Rings and Beowulf: I need a hero! (100 points) Directions: 1. On your own paper, and as you watch the selected scenes, answer the following questions by comparing and contrasting the heroism of Frodo Baggins to that of Beowulf. (The scene numbers are from the extended version; however, the scene titles are consistent with the regular edition.) 2. Use short answer but complete sentences. Fellowship of the Ring Scene 10: The Shadow of the Past Gandalf already has shown Frodo the One Ring and has told Frodo he must keep it hidden and safe. Frodo obliges. But when Gandalf tells him the story of the ring and that Frodo must take it out of the Shire, Frodo’s reaction is different. 1. Explain why Frodo reacts the way he does. Is this behavior fitting for a hero? Why or why not? Is Frodo a hero at this point of the story? 2. How does this differ from Beowulf’s call to adventure? Scene 27: The Council of Elrond Leaders from across Middle Earth have gathered in the Elvish capital of Rivendell to discuss the fate of the One Ring. Frodo has taken the ring to Rivendell for safekeeping. Having already tried unsuccessfully to destroy the ring, the leaders argue about who should take it to be consumed in the fires of Mordor. Frodo steps forward and accepts the challenge. 1. Frodo’s physical stature makes this journey seem impossible. What kinds of traits apparent so far in the story will help him overcome this deficiency? 2. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

The Comforts: the Image of Home in <I>The Hobbit</I>

Volume 14 Number 1 Article 6 Fall 10-15-1987 All the Comforts: The Image of Home in The Hobbit & The Lord of the Rings Wayne G. Hammond Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hammond, Wayne G. (1987) "All the Comforts: The Image of Home in The Hobbit & The Lord of the Rings," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 14 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol14/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Examines the importance of home, especially the Shire, as metaphor in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Relates it to the importance of change vs. permanence as a recurring theme in both works. -

Small Renaissances Engendered in JRR Tolkien's Legendarium

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2017 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Dominic DiCarlo Meo Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meo, Dominic DiCarlo, "'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 555. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/555 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Abstract After surviving the trenches of World War I when many of his friends did not, Tolkien continued as the rest of the world did: moving, growing, and developing, putting the darkness of war behind. He had children, taught at the collegiate level, wrote, researched. Then another Great War knocked on the global door. His sons marched off, and Britain was again consumed. The "War to End All Wars" was repeating itself and nothing was for certain. In such extended dark times, J. R. R. Tolkien drew on what he knew-language, philology, myth, and human rights-peering back in history to the mythologies and legends of old while igniting small movements in modern thought. Arthurian, Beowulfian, African, and Egyptian myths all formed a bedrock for his Legendarium, and fantasy-fiction as we now know it was rejuvenated.Just like the artists, authors, and thinkers from the Late Medieval period, Tolkien summoned old thoughts to craft new creations that would cement themselves in history forever. -

Gandalf: One Wizard to Lead Them, One to Find Them, One to Bring Them And, Despite the Darkness, Unite Them

Mythmoot III: Ever On Proceedings of the 3rd Mythgard Institute Mythmoot BWI Marriott, Linthicum, Maryland January 10-11, 2015 Gandalf: One Wizard to lead them, one to find them, one to bring them and, despite the darkness, unite them. Alex Gunn Middle Earth is a wonderful but strangely familiar place. The Hobbits, Elves, Men and other peoples who live in caves, forests, mountain ranges and stone cities, are all combined by Tolkien to create a fantasy world which is full of wonder, beauty and magic. However, looking past these fantastical elements, we can see that Middle Earth has many similarities to the society in which we live. The different races of Middle Earth have distinct and deep differences and often keep themselves separate from one another because of mutual distrust or dislike. Due to these divisions, only one person, one who does not belong to any particular race or people, can unite them for the coming war: Gandalf the Wizard who embodies the qualities needed to be an effective leader in our world. As Sue Kim points out in her book Beyond black and White: Race and Postmodernism in Lord of the Rings, Tolkien himself declared that, “the desire to converse with other living things is one of the great allurements of fantasy” (Kim 555). Given this belief, it is no surprise that Tolkien,‘fills his imagined worlds with a plethora of intelligent non human races and exotic ethnicities, all changing over time: Elves, Dwarves, Men, Hobbits, Ents, Trolls, Orcs, Wild Men, talking beasts and embodied spirits’ (Kim 555). This plethora, as Kim puts it, makes Gandalf an important literary tool for Tolkien because to believe that such a varied mix of people, creatures, races and ethnicities live in complete harmony would feel false and perhaps too convenient. -

Readers' Guide

Readers’ Guide for by J.R.R. Tolkien ABOUT THE BOOK Bilbo Baggins is a hobbit— a hairy-footed race of diminutive peoples in J.R.R. Tolkien’s imaginary world of Middle-earth — and the protagonist of The Hobbit (full title: The Hobbit or There and Back Again), Tolkien’s fantasy novel for children first published in 1937. Bilbo enjoys a comfortable, unambitious life, rarely traveling any farther than his pantry or cellar. He does not seek out excitement or adventure. But his contentment is dis- turbed when the wizard Gandalf and a company of dwarves arrive on his doorstep one day to whisk him away on an adventure. They have launched a plot to raid the treasure hoard guarded by Smaug the Magnificent, a large and very dangerous dragon. Bilbo reluctantly joins their quest, unaware that on his journey to the Lonely Mountain he will encounter both a magic ring and a frightening creature known as Gollum, and entwine his fate with armies of goblins, elves, men and dwarves. He also discovers he’s more mischievous, sneaky and clever than he ever thought possible, and on his adventure, he finds the courage and strength to do the most surprising things. The plot of The Hobbit, and the circumstances and background of magic ring, later become central to the events of Tolkien’s more adult fantasy sequel, The Lord of the Rings. “One of the best children’s books of this century.” — W. H. AUDEN “One of the most freshly original and delightfully imaginative books for children that have appeared in many a long day . -

Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings Lisa Hillis This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in English at Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1992 Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings Lisa Hillis This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hillis, Lisa, "Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings" (1992). Masters Theses. 2182. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2182 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for i,\1.clusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for iqclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Ef\i.stern Illinois University not allow my thes~s be reproduced because --------------- Date Author m Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings (TITLE) BY Lisa Hillis THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DECREE OF Master .of Arts 11': THE GRADUATE SCHOOL. -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

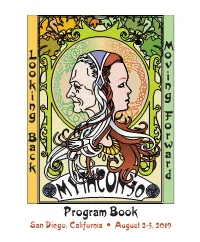

Mythcon 50 Program Book

M L o o v o i k n i g n g F o r B w a a c r k d Program Book San Diego, California • August 2-5, 2019 Mythcon 50: Moving Forward, Looking Back Guests of Honor Verlyn Flieger, Tolkien Scholar Tim Powers, Fantasy Author Conference Theme To give its far-flung membership a chance to meet, and to present papers orally with audience response, The Mythopoeic Society has been holding conferences since its early days. These began with a one-day Narnia Conference in 1969, and the first annual Mythopoeic Conference was held at the Claremont Colleges (near Los Angeles) in September, 1970. This year’s conference is the third in a series of golden anniversaries for the Society, celebrating our 50th Mythcon. Mythcon 50 Committee Lynn Maudlin – Chair Janet Brennan Croft – Papers Coordinator David Bratman – Programming Sue Dawe – Art Show Lisa Deutsch Harrigan – Treasurer Eleanor Farrell – Publications J’nae Spano – Dealers’ Room Marion VanLoo – Registration & Masquerade Josiah Riojas – Parking Runner & assistant to the Chair Venue Mythcon 50 will be at San Diego State University, with programming in the LEED Double Platinum Certified Conrad Prebys Aztec Student Union, and onsite housing in the South Campus Plaza, South Tower. Mythcon logo by Sue Dawe © 2019 Thanks to Carl Hostetter for the photo of Verlyn Flieger, and to bg Callahan, Paula DiSante, Sylvia Hunnewell, Lynn Maudlin, and many other members of the Mythopoeic Society for photos from past conferences. Printed by Windward Graphics, Phoenix, AZ 3 Verlyn Flieger Scholar Guest of Honor by David Bratman Verlyn Flieger and I became seriously acquainted when we sat across from each other at the ban- quet of the Tolkien Centenary Conference in 1992. -

Saruman of Many Colors

University of Iceland School of Humanities Departement of English Saruman of Many Colors A Hero of Liberal Pragmatism B.A. Essay Elfar Andri Aðalsteinsson Kt.: 1508922369 Supervisor: Matthew Whelpton May 2017 ABSTRACT This essay explores the role of the wizard Saruman the White in The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien, and challenges the common conception that Saruman is a villain, instead arguing that Saruman is a hero espousing the values of liberal pragmatism. The policy goals and implicit values of Saruman are contested with his peer and ultimately opponent, Gandalf the Grey, later the White. Both wizards attempt to defeat Sauron but, where Saruman considers new methods, such as recruting the orcs, Gandalf is stuck in old methods and prejudices, as he is unwilling look for new races to recruit. Both wizards construct alliances to accomplish their goals but the racial composition of these alliances can be used to see the wizards in a new light. While Gandalf offers a conventional alliance of “the free” races of Middle Earth (Elves Dwarves, Men. Hobbits and Ents), Saruman can be seen as uniting the marginalised and down-trodden people and races, under a common banner with a common goal. In particular, Saruman brings enemies together into a strong functioning whole, showing that orcs and men can work and prosper together. Gandalf’s blinkered conservatism and Saruman’s pragmatic embrace of diversity are reflected symbolically in the symbolism of white and the rainbow of many colors. After examining all these points it becomes clear that Saruman the White is not the villain that he is assumed to be by Gandalf the Grey, later the White, and his followers in Middle Earth. -

The Hobbit and Tolkien's Mythology Ed. Bradford Lee Eden

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SWOSU Digital Commons (Southwestern Oklahoma State University) Volume 37 Number 1 Article 23 10-15-2018 The Hobbit and Tolkien's Mythology Ed. Bradford Lee Eden David L. Emerson Independent Scholar Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Emerson, David L. (2018) "The Hobbit and Tolkien's Mythology Ed. Bradford Lee Eden," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 37 : No. 1 , Article 23. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss1/23 This Book Reviews is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico • Postponed to: July 30 – August 2, 2021 Additional Keywords Hobbit; Lord of the Rings This book reviews is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss1/23 Reviews moves on to the other element of his cross-disciplinary equation and provides a short history of modern fantasy and theories about the genre; much of this will already be familiar to most readers of Mythlore, at least.