4. Lecture 4 Visualizing Rings We Describe Several Ways of Visualizing Rings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commutative Algebra

Commutative Algebra Andrew Kobin Spring 2016 / 2019 Contents Contents Contents 1 Preliminaries 1 1.1 Radicals . .1 1.2 Nakayama's Lemma and Consequences . .4 1.3 Localization . .5 1.4 Transcendence Degree . 10 2 Integral Dependence 14 2.1 Integral Extensions of Rings . 14 2.2 Integrality and Field Extensions . 18 2.3 Integrality, Ideals and Localization . 21 2.4 Normalization . 28 2.5 Valuation Rings . 32 2.6 Dimension and Transcendence Degree . 33 3 Noetherian and Artinian Rings 37 3.1 Ascending and Descending Chains . 37 3.2 Composition Series . 40 3.3 Noetherian Rings . 42 3.4 Primary Decomposition . 46 3.5 Artinian Rings . 53 3.6 Associated Primes . 56 4 Discrete Valuations and Dedekind Domains 60 4.1 Discrete Valuation Rings . 60 4.2 Dedekind Domains . 64 4.3 Fractional and Invertible Ideals . 65 4.4 The Class Group . 70 4.5 Dedekind Domains in Extensions . 72 5 Completion and Filtration 76 5.1 Topological Abelian Groups and Completion . 76 5.2 Inverse Limits . 78 5.3 Topological Rings and Module Filtrations . 82 5.4 Graded Rings and Modules . 84 6 Dimension Theory 89 6.1 Hilbert Functions . 89 6.2 Local Noetherian Rings . 94 6.3 Complete Local Rings . 98 7 Singularities 106 7.1 Derived Functors . 106 7.2 Regular Sequences and the Koszul Complex . 109 7.3 Projective Dimension . 114 i Contents Contents 7.4 Depth and Cohen-Macauley Rings . 118 7.5 Gorenstein Rings . 127 8 Algebraic Geometry 133 8.1 Affine Algebraic Varieties . 133 8.2 Morphisms of Affine Varieties . 142 8.3 Sheaves of Functions . -

(AS) 2 Lecture 2. Sheaves: a Potpourri of Algebra, Analysis and Topology (UW) 11 Lecture 3

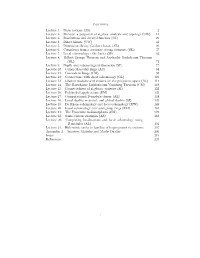

Contents Lecture 1. Basic notions (AS) 2 Lecture 2. Sheaves: a potpourri of algebra, analysis and topology (UW) 11 Lecture 3. Resolutions and derived functors (GL) 25 Lecture 4. Direct Limits (UW) 32 Lecture 5. Dimension theory, Gr¨obner bases (AL) 49 Lecture6. Complexesfromasequenceofringelements(GL) 57 Lecture7. Localcohomology-thebasics(SI) 63 Lecture 8. Hilbert Syzygy Theorem and Auslander-Buchsbaum Theorem (GL) 71 Lecture 9. Depth and cohomological dimension (SI) 77 Lecture 10. Cohen-Macaulay rings (AS) 84 Lecture 11. Gorenstein Rings (CM) 93 Lecture12. Connectionswithsheafcohomology(GL) 103 Lecture 13. Graded modules and sheaves on the projective space(AL) 114 Lecture 14. The Hartshorne-Lichtenbaum Vanishing Theorem (CM) 119 Lecture15. Connectednessofalgebraicvarieties(SI) 122 Lecture 16. Polyhedral applications (EM) 125 Lecture 17. Computational D-module theory (AL) 134 Lecture 18. Local duality revisited, and global duality (SI) 139 Lecture 19. De Rhamcohomologyand localcohomology(UW) 148 Lecture20. Localcohomologyoversemigrouprings(EM) 164 Lecture 21. The Frobenius endomorphism (CM) 175 Lecture 22. Some curious examples (AS) 183 Lecture 23. Computing localizations and local cohomology using D-modules (AL) 191 Lecture 24. Holonomic ranks in families of hypergeometric systems 197 Appendix A. Injective Modules and Matlis Duality 205 Index 215 References 221 1 2 Lecture 1. Basic notions (AS) Definition 1.1. Let R = K[x1,...,xn] be a polynomial ring in n variables over a field K, and consider polynomials f ,...,f R. Their zero set 1 m ∈ V = (α ,...,α ) Kn f (α ,...,α )=0,...,f (α ,...,α )=0 { 1 n ∈ | 1 1 n m 1 n } is an algebraic set in Kn. These are our basic objects of study, and include many familiar examples such as those listed below. -

![Arxiv:1708.03199V5 [Math.AC] 28 Jan 2020 1] N a N Te Otiilcaatrztoso Noetherian of Characterizations Spectrum](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9342/arxiv-1708-03199v5-math-ac-28-jan-2020-1-n-a-n-te-otiilcaatrztoso-noetherian-of-characterizations-spectrum-2079342.webp)

Arxiv:1708.03199V5 [Math.AC] 28 Jan 2020 1] N a N Te Otiilcaatrztoso Noetherian of Characterizations Spectrum

ZARISKI COMPACTNESS OF MINIMAL SPECTRUM AND FLAT COMPACTNESS OF MAXIMAL SPECTRUM ABOLFAZL TARIZADEH Abstract. In this article, Zariski compactness of the minimal spectrum and flat compactness of the maximal spectrum are char- acterized. 1. Introduction The minimal spectrum of a commutative ring, specially its compact- ness, has been the main topic of many articles in the literature over the years and it is still of current interest, see e.g. [1], [2], [4], [5], [6], [7], [9], [10], [13], [15]. Amongst them, the well-known result of Quentel [13, Proposition 1] can be considered as one of the most important results in this context. But his proof, as presented there, is sketchy. In fact, it is merely a plan of the proof, not the proof itself. In the present article, i.e. Theorem 4.9 and Corollary 4.11, a new and purely algebraic proof is given for this non-trivial result. Dually, a new result is also given for the compactness of the maximal spectrum with respect to the flat topology, see Theorem 4.5. In Theorem 3.1, the patch closures are computed in a certain way. This result plays a major role in proving Theorem 4.9. The noetheri- aness of the prime spectrum with respect to the Zariski topology is also arXiv:1708.03199v5 [math.AC] 28 Jan 2020 characterized, see Theorem 5.1. It is worth mentioning that in [11] and [14], one can find other nontrivial characterizations of noetherianness of the prime spectrum. 2. Preliminaries Here, we briefly recall some material which is needed in the sequel. -

Algebraic Geometry UT Austin, Spring 2016 M390C NOTES: ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY

Algebraic Geometry UT Austin, Spring 2016 M390C NOTES: ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY ARUN DEBRAY MAY 5, 2016 These notes were taken in UT Austin’s Math 390c (Algebraic Geometry) class in Spring 2016, taught by David Ben-Zvi. I live-TEXed them using vim, and as such there may be typos; please send questions, comments, complaints, and corrections to [email protected]. Thanks to Shamil Asgarli, Adrian Clough, Feng Ling, Tom Oldfield, and Souparna Purohit for fixing a few mistakes. Contents 1. The Course Awakens: 1/19/163 2. Attack of the Cones: 1/21/166 3. The Yoneda Chronicles: 1/26/16 10 4. The Yoneda Chronicles, II: 1/28/16 13 5. The Spectrum of a Ring: 2/2/16 16 6. Functoriality of Spec: 2/4/16 20 7. The Zariski Topology: 2/9/16 23 8. Connectedness, Irreducibility, and the Noetherian Condition: 2/11/16 26 9. Revenge of the Sheaf: 2/16/16 29 10. Revenge of the Sheaf, II: 2/18/16 32 11. Locally Ringed Spaces: 2/23/16 34 12. Affine Schemes are Opposite to Rings: 2/25/16 38 13. Examples of Schemes: 3/1/16 40 14. More Examples of Schemes: 3/3/16 44 15. Representation Theory of the Multiplicative Group: 3/8/16 47 16. Projective Schemes and Proj: 3/10/16 50 17. Vector Bundles and Locally Free Sheaves: 3/22/16 52 18. Localization and Quasicoherent Sheaves: 3/24/16 56 19. The Hilbert Scheme of Points: 3/29/16 59 20. Differentials: 3/31/16 62 21. -

1. Spectrum of a Ring All the Rings Are Assumed to Be Commutative. Let A

1. Spectrum of a Ring All the rings are assumed to be commutative. Let A be a ring. The spectrum of A denoted by Spec A is the set of prime ideals of A: For any subset T of A; we denote V (T ) the set of all prime ideals containing T: For f 2 A; we denote D(f) the complement of V (f): Proposition 1.1. The spectrum of A is empty if and only if A is the zero ring. Proof. If A is the zero ring, there is no proper prime ideal of A: Hence Spec A is empty. If A is a nonzero ring, A has a maximal ideal (by Zorn's lemma) (or every ideal is contained in a maximal ideal we can choose the zero ideal). Then Spec A is nonempty. Hence we assume that A is a ring with identity 1 and hence A is not a zero ring. Proposition 1.2. Let A be a ring. Suppose that T;S are subsets of A and I;J are ideals of A; f 2 A: (1) If T ⊂ S; then V (T ) ⊃ V (S): (2) LetphT i be the ideal generated by T: Wep have V (T ) = V (hT i): (3) If I is the radical of I; then V (I) = V ( I): (4) V (I) = ; if and only if I isp the unitp ideal. (5) V (I) = V (J) if and only if I = J: (6) D(f) = ; if and only if f is nilpotent. (7) If D(f) = Spec A; then f is a unit. -

On the K-Theory Spectrum of a Ring of Algebraic Integers

ON THE K-THEORY SPECTRUM OF A RING OF ALGEBRAIC INTEGERS W. G. Dwyer and S. A. Mitchell University of Notre Dame University of Washington 1. Introduction § Suppose that F is a number field (i.e. a finite algebraic extension of the field Q of rational numbers) and that F is the ring of algebraic integers in F . One of the most fascinating and apparentlyO difficult problems in algebraic K-theory is to compute the groups Ki F . These groups were shown to be finitely generated by Quillen [36] and their ranksO were calculated by Borel [7]. Lichtenbaum and Quillen have formulated a very explicit conjecture about what the groups should be [37]. Nevertheless, there is not a single number field F for which Ki F is known for any i 5. For most fields F , these groups are unknown for i 3. O ≥ ≥ The groups Ki F are the homotopy groups of a spectrum K F (“spectrum” in the sense of algebraicO topology [1]). In this paper, rather than concentratingO on the individual groups Ki F , we study the entire spectrum K F from the viewpoint of stable homotopy theory.O For technical reasons, it is actuallyO more convenient to single out a rational prime number ℓ and study instead the spectrum KRF , where R = [1/ℓ] is the ring of algebraic ℓ-integers in F . “At ℓ”, that is, after F OF localizing or completing at ℓ, the spectra K F and KRF are almost the same (cf. [34] and [35, p. 113]). O The main results. We will begin by describing the two basic results in this paper. -

SPECTRAL ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY 1. Introduction This Chapter

SPECTRAL ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY CHARLES REZK 1. Introduction This chapter is a very modest introduction to some of the ideas of spectral algebraic geometry, following the approach due to Lurie. The goal is to introduce a few of the basic ideas and definitions, with the goal of understanding Lurie's characterization of highly structured elliptic cohomology theories. 1.1. A motivating example: elliptic cohomology theories. Generalized cohomology theories are functors which take values in some abelian category. Traditionally, we consider ones which take values in abelian groups, but we can work more generally. For instance, take cohomology theories which take values in sheaves of graded abelian groups (or rings) on some given topological space, or in sheaves of graded OS-modules (or rings) on S, where S is a scheme, or possibly a more general kind of geometric object, such as a Deligne-Mumford stack, and OS is its structure sheaf. Given a scheme (or Deligne-Mumford stack) S, it is easy to construct an example of a cohomology theory taking values in graded OS-algebras; for instance, using ordinary cohomology, we can form ∗ ∗ F (X) := U 7! H (X; OS(U)) ; which is a presheaf of graded OS-algebras on S, which in turn can be sheafified into a sheaf of graded OS-modules on S. A more interesting example is given by elliptic cohomology theories. These consist of (1) an elliptic curve π : C ! S (which is in particular an algebraic group with an identity section e: S ! C), (2) a multiplicative generalized cohomology theory F ∗ taking values in sheaves graded commu- odd tative OS-algebras, which is even and weakly 2-periodic in the sense that F (point) ≈ 0 0 2 while F (point) ≈ OS and F (point) is an invertible OS-module, together with (3) a choice of isomorphism 0 1 ∼ ^ α: Spf F (CP ) −! Ce of formal groups, where the right-hand side denotes the formal completion of the elliptic curve π : C ! S at the identity section. -

Short Steps in Noncommutative Geometry

SHORT STEPS IN NONCOMMUTATIVE GEOMETRY AHMAD ZAINY AL-YASRY Abstract. Noncommutative geometry (NCG) is a branch of mathematics concerned with a geo- metric approach to noncommutative algebras, and with the construction of spaces that are locally presented by noncommutative algebras of functions (possibly in some generalized sense). A noncom- mutative algebra is an associative algebra in which the multiplication is not commutative, that is, for which xy does not always equal yx; or more generally an algebraic structure in which one of the principal binary operations is not commutative; one also allows additional structures, e.g. topology or norm, to be possibly carried by the noncommutative algebra of functions. These notes just to start understand what we need to study Noncommutative Geometry. Contents 1. Noncommutative geometry 4 1.1. Motivation 4 1.2. Noncommutative C∗-algebras, von Neumann algebras 4 1.3. Noncommutative differentiable manifolds 5 1.4. Noncommutative affine and projective schemes 5 1.5. Invariants for noncommutative spaces 5 2. Algebraic geometry 5 2.1. Zeros of simultaneous polynomials 6 2.2. Affine varieties 7 2.3. Regular functions 7 2.4. Morphism of affine varieties 8 2.5. Rational function and birational equivalence 8 2.6. Projective variety 9 2.7. Real algebraic geometry 10 2.8. Abstract modern viewpoint 10 2.9. Analytic Geometry 11 3. Vector field 11 3.1. Definition 11 3.2. Example 12 3.3. Gradient field 13 3.4. Central field 13 arXiv:1901.03640v1 [math.OA] 9 Jan 2019 3.5. Operations on vector fields 13 3.6. Flow curves 14 3.7. -

![Arxiv:1503.04299V3 [Math.AC] 18 Jan 2016 Lsdsbe Fteflttplg Ntepiesetu Spec( Spectrum E Prime the Speaking, Roughly on Topology](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1710/arxiv-1503-04299v3-math-ac-18-jan-2016-lsdsbe-fte-ttplg-ntepiesetu-spec-spectrum-e-prime-the-speaking-roughly-on-topology-4541710.webp)

Arxiv:1503.04299V3 [Math.AC] 18 Jan 2016 Lsdsbe Fteflttplg Ntepiesetu Spec( Spectrum E Prime the Speaking, Roughly on Topology

ON THE FLAT TOPOLOGY (I) ABOLFAZL TARIZADEH Abstract. In this article we establish a new and not necessarily Hausdorff topology on the prime spectrum which we call it the flat topology. Then we prove the basic properties of the flat topology specially, various interesting characterizations in terms of the flat topology are given. 1. Introduction The prime spectrum of a commutative ring with identity element is a set whose elements are the prime ideals of this ring; this set equipped with the Zariski topology and also equipped with a certain sheaf of rings (so-called the structure sheaf) is a basic object for studies in Grothendieck algebraic geometry. Nowadays what we call the Zariski topology is essentially due to Grothendieck; Zariski initially introduced a topology on an arbitrary algebraic variety, by taking its algebraic subsets as closed sets; Grothendieck by establishing a correspondence between the points of an affine variety and the maximal ideals of its coordinate ring (by taking varieties over an algebraically closed filed and then using Hilbert’s Nullstellensatz; e.g., consider [8]), transferred Zariski’s topology to the set of prime ideals of an arbitrary commu- tative ring; however the same type of topology had been introduced on the spectra of the boolean algebras much earlier by Marshall Stone [16]. The prime spectrum have been studied extensively from various aspects and points of view (cf. [5], [6], [7], [9], [12], [14], [15]). In arXiv:1503.04299v3 [math.AC] 18 Jan 2016 this article we introduce a new and not necessarily Hausdorff topology on the prime spectrum which we shall call it the flat topology. -

11. Schemes to Define Schemes, Just As with Algebraic Varieties, the Idea

11. Schemes To define schemes, just as with algebraic varieties, the idea is to first define what an affine scheme is, and then realise an arbitrary scheme, as something which is locally an affine scheme. The definition of an affine scheme is motivated by the correspondence between affine varieties and finitely generated algebras over a field, without nilpotents. The idea is that we should be able to associate to any ring R, a topological space X, and a set of continuous functions on X, which is equal to R. In practice this is too much to expect and we need to work with a slightly more general object than a continuous function. Now if X is an affine variety, the points of X are in correspondence with the maximal ideals of the coordinate ring A = A(X). Unfortu- nately if we have two arbitrary rings R and S, then the inverse image of a maximal ideal won't be maximal. However it is easy to see that the inverse image of a prime ideal is a prime ideal. Definition 11.1. Let R be a ring. X = Spec R denotes the set of prime ideals of R. X is called the spectrum of R. Note that given an element of R, we may think of it as a function on X, by considering it value in the quotient. Example 11.2. It is interesting to see what these functions look like in specific cases. Suppose that we take X = Spec k[x; y]. Now any element f = f(x; y) 2 k[x; y] defines a function on X. -

Theoretical Computer Science the Zariski Spectrum As a Formal Geometry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Theoretical Computer Science 405 (2008) 101–115 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Theoretical Computer Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tcs The Zariski spectrum as a formal geometry$ Peter Schuster Mathematisches Institut, Universität München, Theresienstraße 39, 80333 München, Germany article info a b s t r a c t Keywords: We choose formal topology to deal in a basic manner with the Zariski spectra of Zariski spectrum commutative rings and their structure sheaves. By casting prime and maximal ideals in Structure sheaf a secondary role, we thus wish to prepare a constructive and predicative framework for Local ring Universal property abstract algebraic geometry. Formal topology In contrast to the classical approach, neither points nor stalks need occur, let alone any Point-free instance of the axiom of choice. As compared with the topos-theoretic treatments that may Constructive be rendered predicative as well, the road we follow is built from more elementary material. Predicative The formal counterpart of the structure sheaf which we present first is our guiding example for a notion of a sheaf on a formal topology. We next define the category of formal geometries, a natural abstraction from that of locally ringed spaces. This allows us to eventually phrase and prove, still within the language of opens and sections, the universal property of the Zariski spectrum. Our version appears to be the only one that is explicitly point-free. © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. -

Spec(R) Y Axiomas De Separación Entre T0 Y T1

Divulgaciones Matem¶aticasVol. 13 No. 2(2005), pp. 90{98 Spec(R) y Axiomas de Separaci¶on entre T0 y T1 Spec(R) y Axiomas de Separaci¶onentre T0 y T1 Jes¶usAntonio Avila¶ G. ([email protected]) Departamento de de Matem¶aticasy Estad¶³stica Universidad del Tolima Ibagu¶e,Colombia Abstract In this paper we characterize the rings whose prime spectrum satisfy some of the separation axioms between T0 and T1. Additionally, the notion of D-ring , m-ring , U-ring and Y-ring are introduced. Finally, some remarks are made on the de¯ned rings. Key words and phrases: ring, prime ideal, prime spectrum, low separation axioms. Resumen En este art¶³culose caracterizan los anillos cuyo espectro primo satisface algunos axiomas de separaci¶onentre T0 y T1: Para esto se introducen las nociones de D-anillo , m-anillo , U-anillo y Y-anillo. Finalmente, se hacen algunos comentarios sobre los anillos de¯nidos. Palabras y frases clave: anillo, ideal primo, espectro primo, axiomas bajos de separaci¶on. 1 Introduction The theory of the prime spectrum of a ring has been developed from 1930. The precursor ideas are in the one to one correspondence between Boolean lattices and Boolean rings (Stone's Theorem). The modern theory was devel- oped by Jacobson and Zariski mainly. Since the spectrum can be seem as a functor from the category of commutative rings with identity to the topolog- ical spaces, a \dictionary" of properties between the objects and morphisms Received 2004/05/11. Revised 2005/09/21. Accepted 2005/10/01. MSC (2000): Primary 54A05.