AKRON, OHIO Larry Ledebur and Jill Taylor1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cortland Savings & Banking

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE September 10, 2007 COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION The Cortland Savings and Banking Company 846619 194 West Main Street Cortland, Ohio 44410 Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland P.O. Box 6387 Cleveland, OH 44101-1387 NOTE: This document is an evaluation of this institution's record of meeting the credit needs of its entire community, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, consistent with safe and sound operation of the institution. This evaluation is not, nor should it be construed as, an assessment of the financial condition of this institution. The rating assigned to this institution does not represent an analysis, conclusion or opinion of the federal financial supervisory agency concerning the safety and soundness of this financial institution. The Cortland Saving and Banking Company, Cortland Ohio CRA Examination Cortland, Ohio September 10, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Institution’s CRA Rating ................................................................................................................ 1 Scope of examination ................................................................................................................... 1 Description of Institution................................................................................................................ 3 Conclusion with Respect to Performance Tests ........................................................................... 4 Description of the Assessment Areas .......................................................................................... -

Ohio Department of Transportation • News Release ODOT Seeking Public Comment on Transportation Plan

Ohio Department of Transportation • News Release DIVISION OF COMMUNICATIONS 1980 West Broad Street • Columbus, Ohio 43223 www.transportation.ohio.gov ODOT Seeking Public Comment on Transportation Plan The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) hereby notifies all interested persons that a draft long range transportation plan called Access Ohio 2040, an update to Ohio’s long-range transportation plan, is available for review and comment. Access Ohio 2040 is a vision for Ohio’s future transportation system that includes eleven recommendations which will guide, inform, and support ODOT’s policies and investment strategies in the coming years. You may provide your comments at www.accessohio2040.com or by visiting one of the locations identified below. Comments concerning Access Ohio 2040 may be submitted through the above website, by e- mail [email protected], or by mail: Jennifer Townley Division of Planning Attn: Charles Dyer Ohio Department of Transportation Mail Stop #3280 1980 West Broad Street Columbus, OH 43223 Written comments must be received by the close of business on January 15, 2014 ODOT Offices: ODOT District 1: 1885 North McCullough St. – Lima, Ohio 45801 ODOT District 2: 317 East Poe Rd. – Bowling Green, Ohio 43402 ODOT District 3: 906 Clark Avenue – Ashland, Ohio 44805 ODOT District 4: 2088 S. Arlington Road. – Akron, Ohio 44306 ODOT District 5: 9600 Jacksontown Road – Jacksontown, OH 43030 ODOT District 6: 400 E. William Street – Delaware, Ohio 43015 ODOT District 7: 1001 Saint Marys Avenue - Sidney, Ohio 45365 ODOT District 7, Poe Avenue Facility: 5994 Poe Avenue – Dayton, Ohio 45414 ODOT District 8: 505 S. -

Northeast Ohio Educational and Transition Services

Northeast Ohio Information Brief Description ABILIKIDS AbiliKids is a private therapy company specialized in Website: http://www.abilikids.com pediatric occupational, physical and speech therapy. Email: [email protected] AbiliKids also provides social skills groups and summer Location: Different locations and phone numbers here camps for children with autism spectrum disorders. ACHIEVEMENT CENTERS FOR CHILDREN, AUTISM Achievement Centers for Children offers a full‐day PROGRAM preschool program (ages 3‐5) and school program (K‐ Website: http://www.achievementcenters.org 2nd grade) for children with ASD. Methodologies include: Location: Different locations and phone numbers here Structured Teaching (TEACCH), Sensory Integration, Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS), Augmentative Communication, Behavioral Analysis/Modification, Floor‐time and Music Therapy. Tuition is paid by the school district of the child’s residence, as well as transportation in most cases. AUTISM SERVICES FOR KIDS Autism Services for Kids (ASK), is a private consulting Website: http://www.autismservicesforkids.com agency that specializes in an ABA (Applied Behavioral Phone: (216) 834‐2881 Analysis), VB (Verbal Behavior), and play therapy Location: 2623 Princeton Rd., Cleveland Heights, OH 44118 approach to teaching children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and other behavioral and/or learning disorders BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTION INSTITUTE OF OHIO (BIIO) It is the mission of the Behavioral Intervention Institute Website: of Ohio to help bring children with autism spectrum and http://www.behavioralinterventioninstituteofohio.com other mental health disorders to their highest potential Phone: (440) 250‐8800 by offering Individualized Education Plan (IEP) support Location: 24865 Detroit Rd., Westlake, OH 44145 services, school and home program consultation and after‐school focus sessions. -

Project Soar Resource Guide 12.2017.Pdf

PROJECT SOAR (SUPPORTING OPIOID ADDICTION RECOVERY) RESOURCE GUIDE TREATMENT + DETOX SERVICES Windsor Laurelwood RECOVERY SUPPORT/HOUSING St. Vincent Charity Medical Center Rosary Hall 35900 Euclid Ave. Willoughby, OH Woodrow Project 2351 E. 22nd St. Cleveland, OH (440) 953-3000 | windsorlaurelwood.com P.O. Box 34235 Parma, OH (216) 363-2580 | stvincentcharity.com/rosaryhall (440) 527-3624 | thewoodrowproject.com South West General Hospital Sober living for women Stella Maris 7265 Old Oak Blvd. Middleburg Heights, OH 1320 Washington Ave. Cleveland, OH (440) 816-8200 The Lantern Center for Recovery (216) 781-0550 | stellamariscleveland.com swgeneral.com/facilities-and-directions/oakview 12160 Triskett Rd. Cleveland, OH (216) 941-5005 | thelantern.info Salvation Army Harbor Light Sober living for men CARE Alliance Health Center 1710 Prospect Ave E, Cleveland, OH 6001 Woodland Ave. Cleveland, OH (216) 619-4699 Lean In Recovery Center (216) 923-5000 | carealliance.org neo.salvationarmy.org/northeastohio/HarborLightPS 18615 Detroit Ave #207 Lakewood, OH (216) 387-6072 | leaninrecovery.com Cleveland Clinic Circle Health Services Sober living for men Lutheran Hospital th 12201 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 1730 W. 25 Street Cleveland, OH (216) 721-4010 | circlehealthservices.org Edna House my.clevelandclinic.org 2007 W 65th St. Cleveland, OH Outpatient assessments: (216)363-2120/Inpatient New Directions (216) 281-7751 | ednahouse.org detox admissions 24/7:(216)363-2122, option 1 30800 Chagrin Boulevard, Cleveland, OH (216) 591-0324 | newdirect.org Northeast Ohio Recovery Residence Network 2490 Lee Blvd, Suite 308 Cleveland Hts, OH Glenbeigh Louis Stokes Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center (216) 860-0696 | neorrn.org 2863 State Route 45 Rock Creek, OH 10101 East Blvd. -

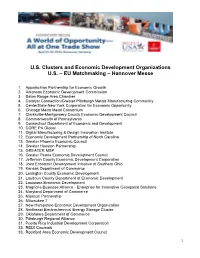

US Cluster/Edos Delegation

U.S. Clusters and Economic Development Organizations U.S. – EU Matchmaking – Hannover Messe 1. Appalachian Partnership for Economic Growth 2. Arkansas Economic Development Commission 3. Baton Rouge Area Chamber 4. Catalyst Connection/Greater Pittsburgh Metals Manufacturing Community 5. CenterState New York Corporation for Economic Opportunity 6. Chicago Metro Metal Consortium 7. Clarksville-Montgomery County Economic Development Council 8. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania 9. Connecticut Department of Economic and Development 10. CORE PA Global 11. Digital Manufacturing & Design Innovation Institute 12. Economic Development Partnership of North Carolina 13. Greater Phoenix Economic Council 14. Greater Houston Partnership 15. GREATER MSP 16. Greater Peoria Economic Development Council 17. Jefferson County Economic Development Corporation 18. Joint Economic Development Initiative of Southern Ohio 19. Kansas Department of Commerce 20. Lexington County Economic Development 21. Loudoun County Department of Economic Development 22. Louisiana Economic Development 23. Magnolia Business Alliance - Enterprise for Innovative Geospatial Solutions 24. Maryland Department of Commerce 25. Missouri Partnership 26. Milwaukee 7 27. New Hampshire Economic Development Organization 28. Northeast Electrochemical Energy Storage Cluster 29. Oklahoma Department of Commerce 30. Pittsburgh Regional Alliance 31. Puerto Rico Industrial Development Corporation 32. REDI Cincinatti 33. Rockford Area Economic Development Council 1 34. Select Greater Philadelphia 35. Team Northeast Ohio 36. Vermont Department of Economic Development 37. Virginia Economic Development Partnership 38. Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation 2 Appalachian Partnership for Economic Growth Nelsonville, Ohio John Molinaro, President and CEO Email: [email protected] Booth Number: Hall 3, Stand F06, (31) Appalachian Partnership for Economic Growth (APEG) promotes economic prosperity in eastern and southern Ohio through business attraction, retention, and expansion efforts and world-class technical assistance. -

Cleveland and Cuyahoga Health Data Matters Redirect to Healthy

Cleveland and Cuyahoga Health Data Matters Redirect to Healthy Northeast Ohio January 28, 2021 Healthy Northeast Ohio welcomes visitors from Cleveland and Cuyahoga Health Data Matters (HDM). As of January 31, 2021, Health Data Matters will terminate as a website. Going forward, visitors will be redirected to Healthy Northeast Ohio. As early champions of open data, Health Data Matters, led by Amy Sheon and Scott Frank at Case Western Reserve University's School of Medicine, offered an invaluable service to health departments and other organizations that wanted to make their data available to the public. Recognizing the importance of social determinants of health, the site enabled visitors to examine the relationships between poverty, education, health outcomes and health disparities, anticipating subsequent widespread interest in these topics. They also made sophisticated data visualization tools available so that people could create maps without having to have or master geographic information software. These tools were of fundamental value in recognizing the compounding effect of neighborhood segregation and poverty on health outcomes and disparities. Finally, Health Data Matters spawned innovation in public health, such as creating the Neighborhood Immersion for Compassion and Empathy Virtual Reality Empathy Training--an immersive experience of neighborhood-level data. By making Health Data Matters available at the Cleveland Medical Hackathon, Amy mentored a generation of health innovators to incorporate attention to the overall impact of their technology. She was especially instrumental in calling attention to place-based disparities in digital connectivity as a social determinant of health. Scott taught a generation of students to use mapping techniques as part of their public health training. -

TAC, CIC and Policy Committee Meeting Packet

Akron Metropolitan Area Transportation Study December 2013 Committee Meetings TECHNICAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Thursday, December 12, 2013, 1:30 p.m. Stow Safety Building 3800 Darrow Road, Stow CITIZENS INVOLVEMENT COMMITTEE Thursday, December 12, 2013, 7:00 p.m. Meeting Room 1 Akron-Summit County Public Library - Main Library, 60 South High Street, Akron POLICY COMMITTEE Thursday, December 19, 2013, 1:30 p.m. PLEASE NOTE NEW MEETING LOCATION: Quaker Station, Quaker Square Inn, The University of Akron Hotel 135 South Broadway, Akron AMATS POLICY COMMITTEE MEETING UNIVERSITY OF AKRON QUAKER SQUARE M ILL ST E V ^_ A FR Y EE PA A RK ING W D A ^_ O R B ^_ ^_ PARKING ENTRANCE ´ ^_ BUILDING ENTRANCE Akron Metropolitan Area Transportation Study Policy Committee Quaker Station, Quaker Square Inn The University of Akron Hotel 135 South Broadway, Akron, Ohio Thursday, December 19, 2013 1:30 p.m. Agenda 1. Call to Order A. Determination of a Quorum Oral B. Audience Participation* 2. Minutes - Motion Required A. September 25, 2013 Meeting Attachment 2A 3. Staff Reports A. Financial Progress Report - Motion Required Attachment 3A B. Technical Progress Report Oral C. AMATS Federal Funds Report Attachment 3C 4. Old Business 5. New Business A. AMATS: The State of Our Region’s Transportation Infrastructure Attachment 5A B. Bicycle Related Crashes 2010-2012 Attachment 5B 6. Resolutions A. Resolution 2013-17 – Conformity Determination and Concurrence Attachment 6A with the Revised Air Quality Conformity Analyses for the Cleveland- Akron Air Quality Area Necessitated by the Amendment to Transportation Outlook 2035 and FY 2014-2017 TIP. -

Popular Annual Financial Report Ended December 31, 2018 Mahoning County, Ohio

Popular Annual Financial Report Ended December 31, 2018 Mahoning County, Ohio Ralph T. Meacham, CPA Mahoning County Auditor Table of Contents Page To the Citizens of Mahoning County ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Mahoning County ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 County Auditor Organizational Chart .................................................................................................................................... 4 Auditor’s Office .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Industry, Commerce and Economic Development ................................................................................................................ 7 Local Government Developments ............................................................................................................................................. 11 Mahoning County – A great place to live, work and play! ................................................................................................. 12 Elected Officials ........................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Economic -

62.4 Report: Profile on Urban Health and Competitiveness in Akron, Ohio

62.4 Report: Profile on Urban Health and Competitiveness in Akron, Ohio Greater Ohio Policy Center January 2016 Acknowledgements This Study was made possible by support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. This Study was primarily researched and written by Torey Hollingsworth, Researcher, and Alison Goebel, Deputy Director at Greater Ohio Policy Center. Cover photo by Shane Wynn, courtesy of akronstock.com. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Comparison Cities ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Quantitative Analysis and Interviews ....................................................................................................... 7 Findings ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 1. Shifting Economies -

Lockheed Martin Corporation 2010 Annual Report

Lockheed Martin Corporation 2010 Annual Report Littoral Combat Ship: Freedom At Sea 2010 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (In millions, except per share data) 2010 2009 2008 Net Sales $ 45,803 $ 43,995 $ 41,372 Segment Operating Profit 5,076 5,104 4,888 Consolidated Operating Profit 4,097 4,415 5,049 Earnings From Continuing Operations 2,645 2,999 3,167 Net Earnings 2,926 3,024 3,217 Earnings Per Diluted Share Continuing Operations 7.18 7.71 7.74 Net Earnings 7.94 7.78 7.86 Cash Dividends Per Common Share 2.64 2.34 1.83 Average Diluted Common Shares Outstanding 368 389 409 Cash, Cash Equivalents and Short-Term Investments $ 2,777 $ 2,737 $ 2,229 Total Assets 35,067 35,111 33,439 Total Debt 5,019 5,052 3,805 Stockholders’ Equity 3,708 4,129 2,865 Common Shares Outstanding at Year-End 346 373 393 Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities 3,547 3,173 4,421 Return on Invested Capital 17.9% 19.9% 21.7% NOTE: For additional information regarding matters affecting the comparability of the information presented above, refer to Selected Financial Data, Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations, and the Consolidated Financial Statements in our 2010 Annual Report on Form 10-K. For additional information concerning return on invested capital, including its definition and use, refer to Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations in our 2010 Annual Report on Form 10-K. DEAR FELLOW SHAREHOLDERS, Thanks to the solid execution of our business strategy in 2010 and the efforts of the dedicated professionals who work for this industry-leading enterprise, we can confidently report that Lockheed Martin remains on course both operationally and financially. -

Goodrich Propeller De-Icers

Proven Goodrich de-icing boots — a trusted leader in de-icing technology and innovation for more than 80 years. Goodrich Propeller De-Icers UTC Aerospace Systems is the manufacturer of Goodrich pneumatic de-icing boots. UTC Aerospace Systems is a pioneer and leading provider of Safety critical ice protection solutions for all-weather operation. In 1932, • Fully tested and FAA certified Goodrich developed the first commercial pneumatic ice protection system for the Northrop Alpha mail plane. We continue to build on Experience our extensive background—applying new de-icing technology to • Expertise in aircraft de-icing for more than 80 years already proven products. Support • Comprehensive support • Installation services For additional information: 1555 Corporate Woods Parkway, Uniontown, OH 44685 U.S.A. Tel: +1 800 DE-ICERS (800 334 2377) Fax: +1 330 374 2290 [email protected] This document does not contain any export controlled technical data. goodrichdeicing.com Goodrich Propeller De-Icers Brush Block Quick Disconnect System Slip Ring Propeller De-icers Total system supplier Continuous innovation UTC Aerospace Systems tests, manufactures and supports virtually UTC Aerospace Systems continues to provide product innovations every component of propeller de-icing systems: de-icers, slip rings, in design, provisioning and support of our propeller ice protection brush blocks, timer, timers with current monitor, wire harnesses, products. Our approach is to provide functional form to innovative ammeters and all other related hardware. ideas such as our Quick Disconnect System (QDS). Ask if QDS is available for your aircraft. Complete engineering design From system concept to field application, UTC Aerospace Systems Worldwide product and technical support does it all. -

2014 Vibrant NEO 2040 Northeast Ohio Sustainable Communities Consortium Executive Summary

Sustainable Communities NEOConsortium Vibrant NEO Guidebook For a More Vibrant, Resilient, and Sustainable Northeast Ohio An Executive Summary of the Vibrant NEO 2040 Vision, Framework & Action Products For Our Future VibrantNEO.org Photo supplied by the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Photo supplied by the Pro Football In 2010, leaders from and representing Northeast Ohio’s 12-county region recognized that our futures are bound together and concluded that our region could be more successful if we worked to anticipate, prepare for, and build that future together, instead of apart. The Northeast Ohio Sustainable Communities Consortium (NEOSCC), was created to figure out how to achieve this goal. NEOSCC’s mission is to create conditions for a more vibrant, resilient, and sustainable Northeast Ohio – a Northeast Ohio that is full of energy and enthusiasm, a good steward of its built and natural resources, and adaptable and responsive to change. NEOSCC Vital Statistics Launched: January 2011 Board Member Organizations: Akron Metropolitan Area Transportation Study (AMATS) | Akron Metropolitan Housing Authority | Akron Urban League | Ashtabula County | Catholic Charities, Diocese of Youngstown | The Center for Community Solutions | City of Akron | City of Cleveland | City of Elyria | City of Youngstown | Cleveland Metroparks | Cleveland Museum of Natural History | Cleveland State University | Cuyahoga County | Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority | Eastgate Regional Council of Governments | Fund for Our Economic Future | Greater Cleveland RTA