The Name Change of North Macedonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 THESSOLONIANS 1:1-10 the Gospel Received in Much Assurance and Much Affliction the Vitality of a Living Christian Faith

1 THESSOLONIANS 1:1-10 The Gospel Received in Much Assurance and Much Affliction The Vitality of a Living Christian Faith Thessalonica was a Roman colony located in Macedonia and not in Greece proper. The city was first named Therma because of the hot springs in that area. In 316 A.D. Cassander, one of the four generals who divided up the empire of Alexander the Great took Macedonia and made Thessalonica his home base. He renamed the city in memory of his wife, Thessalonike, who was a half sister of Alexander. The city is still in existence and is now known as Salonika. Rome had a somewhat different policy with their captured people from what many other nations have had. For example, it seems that we try to Americanize all the people throughout the world, as if that would be the ideal. Rome was much wiser than that. She did not attempt to directly change the culture, the habits, the customs, or the language of the people whom she conquered. Instead, she would set up colonies which were arranged geographically in strategic spots throughout the empire. A city which was a Roman colony would gradually adopt Roman laws and customs and ways. In the local department stores you would see the latest things they were wearing in Rome itself. Thus these colonies were very much like a little Rome. Thessalonica was such a Roman colony, and it was an important city in the life of the Roman Empire. It was Cicero who said, “Thessalonica is in the bosom of the empire.” It was right in the center or the heart of the empire and was the chief city of Macedonia. -

Draft Assessment Report: Skopje, North Macedonia

Highlights of the draft Assessment report for Skopje, North Macedonia General highlights about the informal/illegal constructions in North Macedonia The Republic of North Macedonia belongs to the European continent, located at the heart of the Balkan Peninsula. It has approx. 2.1 million inhabitants and are of 25.713 km2. Skopje is the capital city, with 506,926 inhabitants (according to 2002 count). The country consists of 80 local self-government units (municipalities) and the city of Skopje as special form of local self-government unit. The City of Skopje consists of 10 municipalities, as follows: 1. Municipality of Aerodrom, 2. Municipality of Butel, 3. Municipality of Gazi Baba, 4. Municipality of Gorche Petrov, 5. Municipality of Karpos, 6. Municipality of Kisela Voda, 7. Municipality of Saraj, 8. Municipality of Centar, 9. Municipality of Chair and 10. Municipality of Shuto Orizari. During the transition period, the Republic of North Macedonia faced challenges in different sectors. The urban development is one of the sectors that was directly affected from the informal/illegally constructed buildings. According to statistical data, in 2019 there was a registration of 886 illegally built objects. Most of these objects (98.4 %) are built on private land. Considering the challenge for the urban development of the country, in 2011 the Government proposed, and the Parliament adopted a Law on the treatment of unlawful constructions. This Law introduced a legalization process. Institutions in charge for implementation of the legalization procedure are the municipalities in the City of Skopje (depending on the territory where the object is constructed) and the Ministry of Transport and Communication. -

The Making of Yugoslavia's People's Republic of Macedonia 377 Ward the Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party Hardened

THE MAKING OF YUGOSLAVIA’S PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Fifty years since the liberation of Macedonia, the perennial "Ma cedonian Question” appears to remain alive. While in Greece it has deF initely been settled, the establishment of a "Macedonian State” within the framework of the People’s Federal Republic of Yugoslavia has given a new form to the old controversy which has long divided the three Balkan States, particularly Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. The present study tries to recount the events which led to its founding, the purposes which prompted its establishment and the methods employed in bringing about the tasks for which it was conceived. The region of Southern Yugoslavia,' which extends south of a line traversed by the Shar Mountains and the hills just north of Skopje, has been known in the past under a variety of names, each one clearly denoting the owner and his policy concerning the region.3 The Turks considered it an integral part of their Ottoman Empire; the Serbs, who succeeded them, promptly incorporated it into their Kingdom of Serbs and Croats and viewed it as a purely Serbian land; the Bulgarians, who seized it during the Nazi occupation of the Balkans, grasped the long-sought opportunity to extend their administrative control and labeled it part of the Bulgarian Father- land. As of 1944, the region, which reverted to Yugoslavia, has been known as the People’s Republic of Macedonia, one of the six federative republics of communist Yugoslavia. The new name and administrative structure, exactly as the previous ones, was intended for the purpose of serving the aims of the new re gime. -

Hymenoptera: Braconidae) from Iran

European Journal of Taxonomy 571: 1–25 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2019.571 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2019 · Zargar M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:89B1D35C-8162-403C-BF95-7853C62D27D1 Three new species and two new records of the genus Cotesia Cameron (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) from Iran Mohammad ZARGAR 1, Ankita GUPTA 2, Ali Asghar TALEBI 3,* & Samira FARAHANI 4 1,3 Department of Entomology, Faculty of Agriculture, Tarbiat Modares University, P.O. Box 14115-336, Tehran, Iran. 2 ICAR-National Bureau of Agricultural Insects Resources, P.B. No. 2491, H.A. Farm Post, Bellary Road, Hebbal, 560 024 Bangalore, India. 4 Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands, Agricultural Research Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), P.O. Box 13185-116, Tehran, Iran. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Email: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 4 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6F685437-6655-4D8B-9DD5-C66A0824B987 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:AC7B7E50-D525-4630-B1E9-365ED5511B79 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:71CB13A9-F9BD-4DDE-8CB1-A495036975FE 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:423DEB84-81C3-4179-BDE2-88A827CD4865 Abstract. The present study is based on the genus Cotesia Cameron,1891 collected from Khuzestan Province in the Southwestern part of Iran during 2016–2017. Nine species (+200 specimens) of the genus Cotesia were collected and identified. We recognised three new species, which we describe and illustrate here: Cotesia elongata Zargar & Gupta sp. -

GO BEYOND the DESTINATION on Our Adventure Trips, Our Guides Ensure You Make the Most of Each Destination

ADVENTURES GO BEYOND THE DESTINATION On our adventure trips, our guides ensure you make the most of each destination. You’ll find hidden bars, explore cobbled lanes, and eat the most delectable meals. Join an adventure, tick off the famous wonders and discover Europe’s best-kept secrets! Discover more Travel Styles and learn about creating your own adventure with the new 2018 Europe brochure. Order one today at busabout.com @RACHAEL22_ ULTIMATE BALKAN ADVENTURE SPLIT - SPLIT 15 DAYS CROATIA Mostar SARAJEVO SERBIA ROMANIA SPLIT BELGRADE (START) BOSNIA Dubrovnik MONTENEGRO Nis BULGARIA KOTOR SKOPJE Budva MACEDONIA OHRID ITALY TIRANA ALBANIA Gjirokaster THESSALONIKI GREECE METEORA Delphi Thermopylae Overnight Stays ATHENS NEED TO KNOW INCLUSIONS • Your fantastic Busabout crew • 14 nights’ accommodation • 14 breakfasts • All coach transport @MISSLEA.LEA • Transfer to Budva • Orientation walks of Thessaloniki, Tirana, Gjirokaster, Nis and Split • Entry into two monasteries in Meteora The Balkans is the wildest part of Europe to travel in. You’ll be enthralled by the cobbled • Local guide in Mostar castle lanes, satiated by strange exotic cuisine, and pushed to your party limits in its • Local guide in Delphi, plus site and offbeat capitals. Go beyond the must-sees and venture off the beaten track! museum entrance FREE TIME Chill out or join an optional activity • 'Game of Thrones' walking tour in Dubrovnik DAY 5 | KALAMBAKA (METEORA) - THERMOPYLAE - ATHENS • Sunset at the fortress in Kotor HIGHLIGHTS We will visit two of the unique monasteries perched • Traditional Montenegrin restaurant dinner • Scale the Old Town walls of Dubrovnik high on top of incredible rocky formations of Meteora! • Bar hopping in Kotor • Breathtaking views of Meteora monasteries After taking in the extraordinary sights we visit the • Traditional Greek cuisine dinner • Be immersed in the unique culture of Sarajevo Spartan Monument in Thermopylae on our way to • Walking tour in Athens • Plus all bolded highlights in the itinerary Athens. -

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

ANNEX 2 Crosstabulations of the Survey Questions with The

"WHO OWNS ALEXANDER THE GREAT?": A QUESTION UPON WHICH EU ENLARGEMENT RELIES ANNEX 2 Crosstabulations of the survey questions with the respondents ethnicity According to you which was the most important period for the formation of Macedonian identity? Ethnicity Macedonian Albanian Turk According to you which Antiquity 7.6% 0.5% was the most important Medieval Slavic Christianity (period of 22.2% 12.5% 21.9% period for formation of Brothers Cyril and Methodius) Macedonian identity? Ilinden Uprising (organized revolt 16.7% 1.9% 18.8% against the Ottoman Empire 1903) Partisan period of WWII 7.6% 4.6% 15.6% SFR Yugoslavia 14.5% 19.0% 18.8% Independence (1991- present) 21.5% 19.4% 12.5% Bucharest agreement (1913) 0.2% I don’t know 7.5% 13.9% 12.5% No answer 2.0% 28.2% They are all important The end of the 19century 0.2% Total 100.0% 100.0% 100.0 % Ethnicity Roma Serbian Vlach Other According to you which Antiquity 4.5% 18.2% was the most important Medieval Slavic Christianity 17.4% 13.6% 32.0% 4.5% period for formation of (period of Brothers Cyril Macedonian identity? and Methodius) Ilinden Uprising (organized 8.7% 18.2% 12.0% 18.2% revolt against the Ottoman Empire 1903) Partisan period of WWII 13.0% 18.2% 12.0% SFR Yugoslavia 32.6% 22.7% 20.0% 45.5% Independence (1991- 8.7% 18.2% 20.0% 13.6% present) Bucharest agreement (1913) I don’t know 15.2% 4.0% No answer 4.3% They are all important 4.5% The end of the 19century Total 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% Ethnicity Total Refuse to answer According to you which was the Antiquity 5.8% most important -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

A THREAT to "STABILITY" Human Rights Violations in Macedonia

Macedoni Page 1 of 10 A THREAT TO "STABILITY" Human Rights Violations in Macedonia Human Rights Watch/Helsinki Human Rights Watch Copyright © June 1996 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 1-56432-170-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-77111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was researched and written by Fred Abrahams, a consultant to Human Rights Watch/Helsinki. It is based primarily on a mission to Macedonia conducted in July and August 1995. During that time, Human Rights Watch/Helsinki spoke with dozens of people from all ethnic groups and political persuasions. Extensive interviews were conducted throughout the country with members of government, leaders of the ethnic communities, human rights activists, diplomats, journalists, lawyers, prison inmates and students. The report was edited by Jeri Laber, Senior Advisor to Human Rights Watch/Helsinki. Anne Kuper provided production assistance. Human Rights Watch/Helsinki would like to thank the many people in Macedonia and elsewhere who assisted in the preparation of this report, especially those who took the time to read early drafts. Thanks also go to those members of the Macedonian government who helped by organizing a prison visit, providing information or granting lengthy interviews. I. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS Macedonia faces difficulties on several fronts. As a former member of the Yugoslav federation, the young republic is in a transition from communism in which it must decentralize its economy, construct democratic institutions and revitalize its civil society. These tasks, demanding under any circumstances, have been made more difficult by Macedonia's proximity to the war in Bosnia. -

Carol Migdalovitz Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Defense Division

Order Code RS21855 Updated October 16, 2007 Greece Update Carol Migdalovitz Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Defense Division Summary The conservative New Democracy party won reelection in September 2007. Kostas Karamanlis, its leader, remained prime minister and pledged to continue free-market economic reforms to enhance growth and create jobs. The government’s foreign policy focuses on the European Union (EU), relations with Turkey, reunifying Cyprus, resolving a dispute with Macedonia over its name, other Balkan issues, and relations with the United States. Greece has assisted with the war on terrorism, but is not a member of the coalition in Iraq. This report will be updated if developments warrant. See also CRS Report RL33497, Cyprus: Status of U.N. Negotiations and Related Issues, by Carol Migdalovitz. Government and Politics Prime Minister Kostas Karamanlis called for early parliamentary elections to be held on September 16, 2007, instead of in March 2008 as otherwise scheduled, believing that his government’s economic record would ensure easy reelection. In August, however, Greece experienced severe and widespread wildfires, resulting in 76 deaths and 270,000 hectares burned. The government attempted to deflect attention from what was widely viewed as its ineffective performance in combating the fires by blaming the catastrophe on terrorists, without proof, and by providing generous compensation for victims. This crisis came on top of a scandal over the state pension fund’s purchase of government bonds at inflated prices. Under these circumstances, Karamanlis’s New Democracy party’s (ND) ability to win of a slim majority of 152 seats in the unicameral 300-seat parliament and four more years in office was viewed as a victory. -

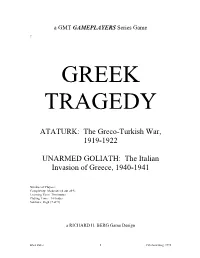

Greek Tragedy Rules II

a GMT GAMEPLAYERS Series Game ? GREEK TRAGEDY ATATURK: The Greco-Turkish War, 1919-1922 UNARMED GOLIATH: The Italian Invasion of Greece, 1940-1941 Number of Players: Complexity: Moderate (4 out of 9) Learning Time: 30 minutes Playing Time: 3-8 hours Solitaire: High (7 of 9) a RICHARD H. BERG Game Design BNA Rules 1 ©Richard Berg, 1995 (1.0) INTRODUCTION A Greek Tragedy covers Greece’s two major wars after WWI: her attempt to seize the Ionian/western portion of Turkey, 1919-22 - the Ataturk game - and the woefully sorry invasion of Greece by Italy during WW II, Unarmed Goliath. In the Gameplayers series, the emphasis is on accessibility and playability, with as much historical flavor as we can muster. Given a choice between playability and historicity, we have tended to “err” on the side of the former. Each campaign has some of its own, specific rules; these are given in that campaign’s Scenario Book. Unless stated otherwise, the rules in this book apply top both campaigns. (2.0) COMPONENTS The game includes the following items: 2 22”x34” game maps ? sheet of combat counters (large) 1 sheet of informational markers (small) 1 Rules Book 2 Scenario Booklets 2 Charts & Tables Cards 1 ten-sided die (2.1) THE MAPS The gamemaps are overlayed with a grid of hexagons - hexes - which are used to regulate movement. The various types of terrain represented are discussed in the rules, below. The map of Greece is used for the Unarmed Goliath scenario; the map of Turkey for Ataturk. The two maps do link up; not that we provide any reason to do so. -

Menu Samples

Menu Samples The Original Quick Six Rosemary Spiked Cannellini Crostini, Spaghetti al Cavolo Nero (Black Kale), Chicken with Herbs De Provence, Popcorn Cauliflower, Nori Crunch Salad with Avocado, Elana's Famous GuiltFree Cobbler The original MEAL that started the SPIEL. Six delicious, healthy and fast recipes including Elana's Famous Guiltfree Cobbler. You will be amazed at how easy it is to make good food and increase your popularity in your circle of friends!! This class is ideal for novices and cooks with more experience and will provide you with a 4 1/2 course dinner party menu (should you decide to accept the challenge), smaller dinner party menus and "quick fixes" just for you. A Quick Six: Hot Mediterranean Menu Roasted Tomato and Burrata Crostini, Pasta with Deconstructed Arugula Pesto, Edo's Mother's Swordfish, Shores of Capperi Potato Salad (no mayo), BiColore Salad, Strawberry Macedonia with Mint A tried and true menu that will transport you to the hotblooded flavors of the southern Mediterranean. (Note, the food is not spicy, just good.) The Quick Six has become one of the signature classes of Meal and a Spiel. Come learn six fast, easy, healthy and delicious recipes that will make you popular amongst your circle of friends. This class is ideal for novices and cooks with more experience and will provide you with a 4 1/2 course dinner party menu (should you decide to accept the challenge), smaller dinner party menus and "quick fixes" just for you. Hot Tuscan Nights Tomato and Basil Bruschetta, Sliced Steak with Arugula, Shaved Parmigiano and a Balsamic Reduction, BakedNotFried Little Potato Sticks with Rosemary and Thyme, Greek Yogurt Panna Cotta with Rosemary Grove Peaches The warm windy Italian countryside sets a perfect tone for a romantic dinner amongst lovers and friends.